If the Supreme Court overturns Roe v. Wade this summer, as a leaked draft opinion suggests it may, abortion will likely be banned or severely restricted in about half of the United States. But that doesn’t necessarily mean the country will return to a world before 1973, when the landmark Supreme Court case enshrined a constitutional right to abortion.

Abortion pills, which can be ordered online and delivered by mail, have already fundamentally changed reproductive rights in America. The regimen of two drugs, mifepristone and misoprostol, can in theory be safely taken anywhere, including in the privacy of people’s homes, eliminating the need to undergo a procedure, travel out of state, take time off work, or confront protestors outside of a clinic. In part because of this convenience, abortion pills—also known as medication abortion—are now the most common method of ending a pregnancy in the U.S.

But abortion rights advocates say that huge obstacles remain in accessing these drugs. Due to a complicated patchwork of legal and regulatory hurdles in different states, combined with societal issues such as poverty and a lack of internet access, many would-be patients either have never heard of abortion pills, or don’t know where to get them, how to take them safely, and whether they’re legal. Medical professionals are often similarly flummoxed. Many who do not currently provide abortions know little about the pills themselves, and abortion providers, who are operating with very few resources, must navigate a maze of misinformation and ever-shifting legal risks on behalf of themselves and their patients. Conservative lawmakers in 19 states have further complicated legal questions by passing laws that effectively prohibit the use of telemedicine and limit where the pills can be administered. Amid this confusing landscape, many are turning to the internet, where they’re confronted with different problems: misleading information, websites designed to mimic reliable organizations, and platforms that can collect their data and take more knowledge to safely navigate.

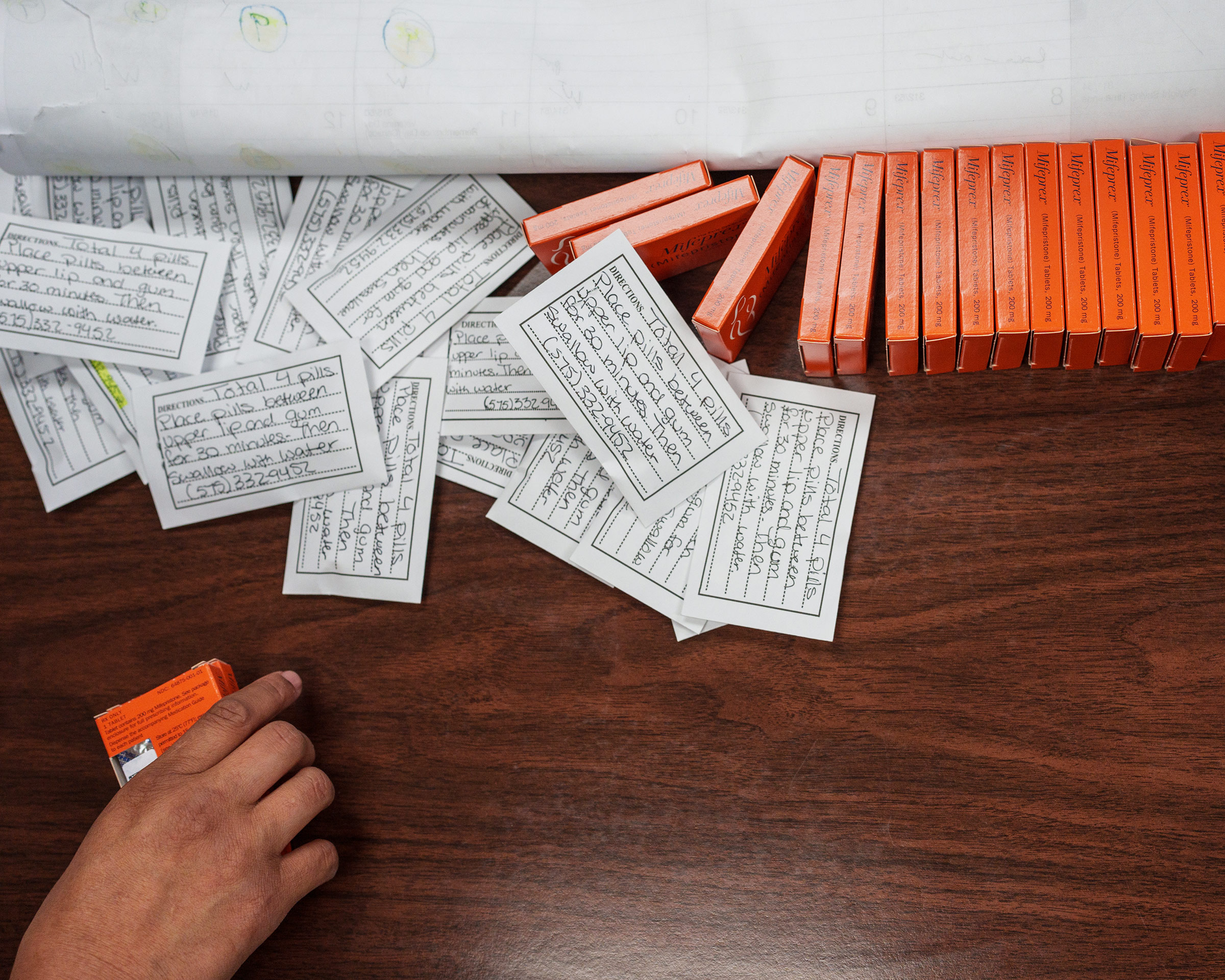

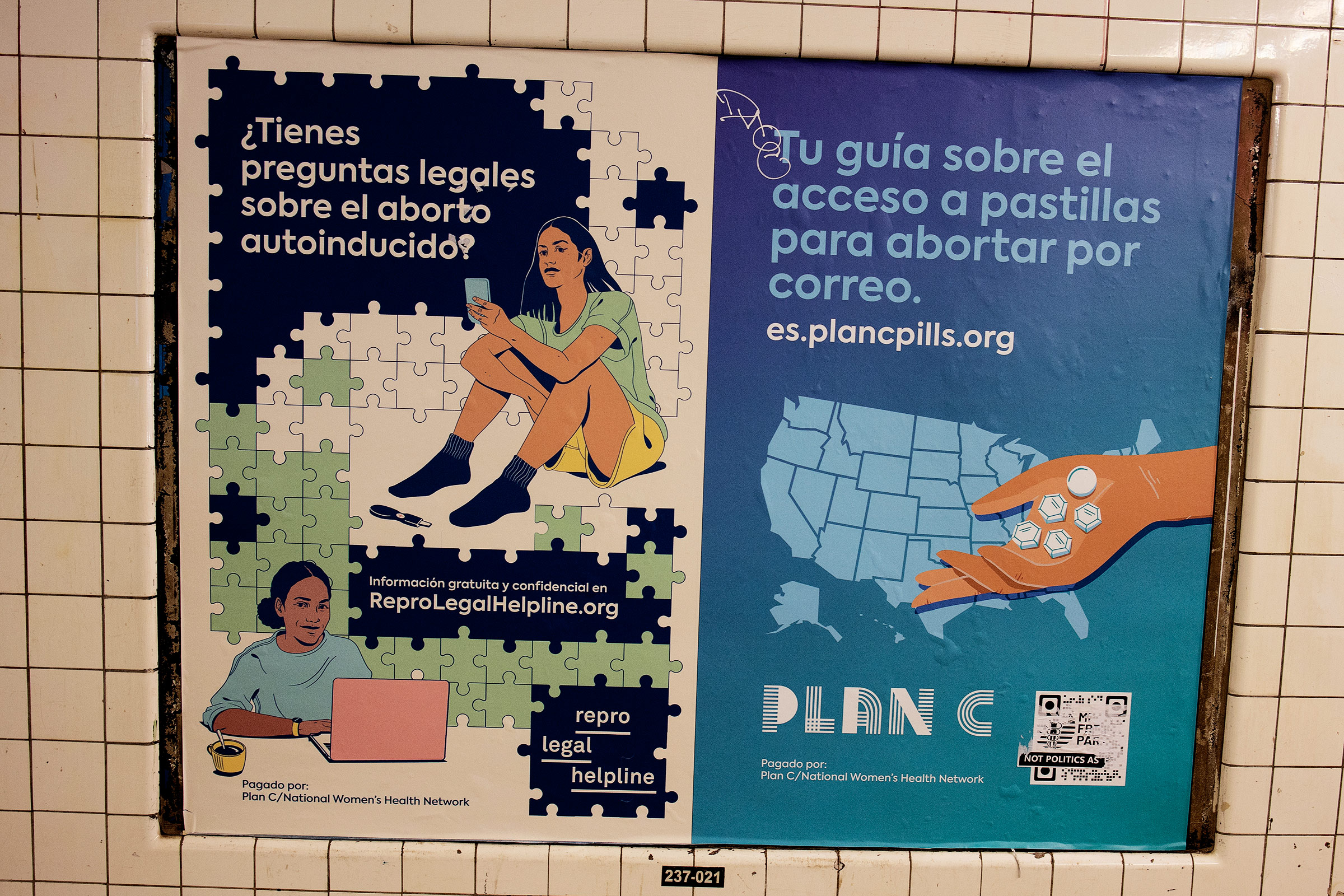

With the Supreme Court poised to overturn Roe and Republican-led states passing ever-more restrictive laws, abortion rights advocates are racing to get ahead of the curve. In the last few months, advocacy groups have published online guides to obtaining abortion pills, purchased ad campaigns on the New York City subway, and launched online courses on how to “self-manage” abortions outside the established health care system. Internet privacy experts have posted toolkits to help individuals protect their digital footprints, and staffed up hotlines that answer medical questions from people taking abortion pills in anticipation of an increase in need. Groups that fund abortions are also raising millions of dollars to help subsidize or cover the cost of the pills for individuals, and to help people travel to states where it will stay legal for providers to prescribe them. Physician organizations are funding programs for medical residents to learn about medication abortion, and encouraging a broad array of doctors to get up to speed on abortion pills, the legal atmosphere around them, and the misinformation that is already starting to circulate online and in state houses around the country.

Elisa Wells, co-founder of Plan C, an organization dedicated to spreading information about how to access and take abortion pills, says medication abortion will be crucial in any post-Roe era. “One of the huge differences between then and now is that you do have these pills, they are in our communities, they are accessible through the internet,” she says. “And we hope that will at least lead to medically safe access to care even when it is restricted.”

A push to inform patients and medical staff about abortion pills

The number of medication abortions has been steadily increasing since mifepristone was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2000. In the U.S., the vast majority of abortions are completed at or before 13 weeks of pregnancy—so abortion pills, which are approved for use up to 10 weeks, are an option for many patients. In 2020, the pills accounted for 54% of U.S. abortions. The uptick was due in part to the COVID-19 pandemic, during which time conservative states forced some brick-and-mortar clinics to temporarily close and access to telehealth appointments increased. Another major factor was an FDA decision in April 2021 to lift restrictions on mailing abortion pills during the pandemic; in December, it extended that policy permanently.

But if the use of medication abortion has increased, access to the drugs has been unevenly distributed, says Ushma Upadhyay, an associate professor at the University of California, San Francisco, who is leading a study of the use of telehealth for abortion pills in 22 states.

“There are many people who don’t know that abortion pills even exist,” she says. “If they do know that abortion pills exist, they don’t know that they can access them through telehealth without an in-person visit, that they don’t have to tell many people about their decision.” Only about 1 in 5 adults had heard of medication abortion in 2020, according to the nonpartisan Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF).

People of color, immigrants, those who live in rural areas, and teenagers are disproportionately unlikely to have access to abortion pills, says Upadhyay. None of the three major medication abortion telehealth companies in her study take Medicaid or offer services in languages other than English, and other companies have similar barriers. Black and Hispanic Americans, low-income people, and those who live far away from cities are less likely to have broadband internet at home, and therefore may struggle to get a prescription via telehealth.

Nearly two-thirds of the first 3,200 patients who have received abortion pills in Upadhyay’s study are white, compared to the national population of abortion patients, which is about 40% white. Upadhyay’s research also shows that 82% of those who have accessed abortion pills live in urban areas and nearly 75% were between 18 and 34 years old.

The challenges of accessing abortion pills in states that ban abortion

While medication abortion is not yet illegal in any state other than Oklahoma which just passed a law banning all abortion from the moment of “fertilization,” legislators in 22 states have introduced a flurry of new bills since January that would severely restrict access to or outright ban abortion pills. Many states have already passed laws requiring the prescribing clinician to be physically present when the pills are administered, effectively banning telehealth appointments in which abortion pills are prescribed, then mailed to a patient. Some have also explicitly banned telehealth for abortions. Three states outlaw self-managed abortion. And while lawmakers have otherwise traditionally targeted abortion providers rather than patients, abortion pills—which patients can get by mail or can order online without a doctor’s involvement—complicate that dynamic.

Not only is it more difficult for officials to enforce laws against providers who don’t live in their state, but the impending Supreme Court decision has also emboldened some anti-abortion lawmakers. On May 4, two days after the Supreme Court leak, lawmakers in Louisiana advanced legislation that would classify all abortion—including medication abortion—as homicide and allow prosecutors to charge patients. While that bill is extreme by any measure, even states that don’t explicitly criminalize patient actions could expose individuals to legal risk.

The arrest of 26-year-old Lizelle Herrera in Texas last month over an alleged self-managed abortion raised concerns about how officials will treat people in states with abortion restrictions on the books. Staff at the hospital where Herrera sought care reported her to law enforcement, resulting in a temporary murder charge. While authorities ultimately dropped the charge, she spent three days in jail. Texas has banned abortions after about six weeks of pregnancy, but that law carries no criminal punishment for individuals who seek out abortions, and no other law applied in this case either.

“I worry about the chilling effect,” says Cynthia Conti-Cook, a civil rights attorney and technology fellow at the Ford Foundation. “The people who are most likely to be targeted for investigation, surveilled and prosecuted … are communities that are majority Black people and immigrant communities, and communities that in any other way have experienced historical oppression.”

Leah Coplon, a certified nurse midwife and director of clinical operations at Abortion on Demand, a group that provides abortion pills by mail in 21 states, says patients ask her about legal liability. While Abortion on Demand only mails pills in states where it is legal to do so, some patients are concerned about scrutiny from health care or law enforcement officials, while others worry their own friends and family, who might not support their decision to get an abortion, could take action to stop them. Coplon explains that because the outcome of a medication abortion looks exactly like a miscarriage, and can be treated as such in a health care setting, patients don’t have to tell anyone they have taken the pills.

Patients who live in any of the 19 states where mailing abortion pills is restricted can still access the pills from an in-person clinic or from international services like the Austrian-based Aid Access, a group founded by Dutch physician Dr. Rebecca Gomperts, which ships abortion pills to all 50 states. For patients in states where mailing pills is legal, Gomperts works with nine U.S.-based providers, and for those in restricted states, she prescribes the pills herself and sources them from a pharmacy in India. In 2019, the FDA demanded that Aid Access stop, saying the generic mifepristone was a “misbranded and unapproved drug,” but Aid Access sued the agency and the FDA ultimately did not take further action against the organization.

Some U.S. providers are also finding workarounds. Dr. Julie Amaon, medical director of telehealth abortion pill company Just the Pill, sometimes tells patients to drive to the nearest state that allows pills to be prescribed by telehealth. She then arranges for the pills to be sent to FedEx, UPS, or Post Office pickup points. Just the Pill is also planning to staff mobile clinics that will travel to states, including Illinois, Pennsylvania, and New Mexico, where abortion will likely remain legal but that border states with strict anti-abortion laws. Such mobile clinics will help “offload all the medication abortions so [brick-and-mortar clinics] can focus on procedures,” Amaon says.

Hey Jane, another telehealth medication abortion company, similarly ships to Post Office boxes and other pickup points in states where abortion is likely to remain broadly legal, including New York, California, Washington, Illinois, Colorado, and New Mexico. Hey Jane CEO Kiki Freedman says she chose those states because they are places that expect to see an influx of patients as GOP-led states ban abortion.

Educating via social media is both crucial and problematic

Melissa Grant, an executive at Carafem, another company that remotely provides abortion pills, says stigma and misinformation can be almost as problematic as legal restrictions.

“You might say, ‘I have a great dentist,’ but it’s rare you’d say, ‘Hey, this is a great place to have an abortion,’” Grant says. “We’ve had to find ways to reach people and let them know we’re not a crisis pregnancy center, we’re real, and you can come here and trust us.”

To that end, Carafem operates a text-message support service to answer patient questions as they self-manage abortions. Other hotlines, including the Repro Legal Helpline and the Miscarriage and Abortion Hotline, which recently increased its team from 40 to 50 volunteers, provide similar support.

Other abortion rights advocates are working to seed search and social media platforms with reliable information. Plan C has built an online directory where people in all 50 states can find services that will send them abortion pills by mail. It also provides information about each state’s laws, as well as the potential legal risks that patients face. Plan C also posts artwork, information, and paid ads about medication abortion across social media platforms. The day after the Supreme Court draft leaked, Plan C saw a huge spike in traffic to its site, reaching 56,000 visitors, up from an average of 2,300 a day before the leak.

“The internet is clearly a huge improvement [from the pre-Roe era] in a lot of ways, and a powerful tool in our ability to share information,” says Wells, Plan C’s co-founder and co-director.

But such information is only useful to those who are able to find it in the first place. Many would-be abortion patients either don’t have private access to the internet, or are fearful that their online search histories could leave them exposed to legal liability, providers and scholars say. Some groups have posted guides to help people protect their data when searching for information about abortions. Others have taken steps to combat disinformation disseminated by anti-abortion groups, which regularly use phrases and imagery in their online advertisements designed to lure people in search of information about abortion, in order to deter them from ending their pregnancies.

Websites for anti-abortion pregnancy centers often feature FAQs about medication abortion, for example, but include warnings that it can be dangerous or encourage people to make an appointment to learn more. Only the fine print clarifies that they do not offer abortions. Other anti-abortion groups also promote “abortion pill reversal” treatments, an idea that the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists says is “not based on science.”

Plan C and other abortion rights advocates say that social media platforms, including Facebook and Instagram, frequently remove their posts, refuse to run ads, or deprioritize their pages with little or no explanation. For example, just days before a Texas law banning abortion after about six weeks took effect last fall, Plan C’s Instagram account was suspended; Plan C was notified it had violated the platform’s community guidelines or terms of use, Wells says. Many of its advertisements and posts still get taken down by Instagram and Facebook, says Martha Dimitratou, Plan C’s social media manager. Facebook ads with language like “there is a safe alternative to in-clinic abortion” and “abortion pills belong in the hands of people who need them” are rejected for violating a Facebook policy that bans ads promoting the sale or use of “unsafe substances,” according to screenshots provided by Dimitratou. An ad promoting an event last month training people on medication abortion and self-managed abortion was rejected for the same reason.

Meta, the parent company of Facebook and Instagram, declined to answer questions about Plan C or other groups’ posts. A spokesperson for Meta said its platforms allow posts and ads that raise awareness of abortion and provide information about abortion, including abortion pills, but the company does not allow direct sales of prescription drugs. All abortion content must also follow the platforms’ policies on topics such as prescription drugs, misinformation, and bullying and harassment.

Dimitratou calls the policies “counterproductive.” “You have to spend a lot of time just through the whole process appealing things and trying to convince them that abortion pills are legal and safe,” she says.

Aid Access has experienced similar problems, says Christie Pitney, a certified nurse midwife who works with the group to prescribe abortion pills in states where telehealth for abortion is legal and helps run the group’s social media. On May 10, as it was seeing a surge in interest following the Supreme Court leak, Aid Access’s Instagram account was suspended, Pitney says. It has since been restored, but she and Gomperts say other issues are ongoing.

Women on Web, another group founded by Gomperts that mails abortion pills all around the world, has seen its Facebook and Instagram ads rejected too, according to screenshots provided by Dimitratou, who runs social media there as well. When Google updated its algorithm in May 2020, Women on Web appeared farther down in search results, leading to a 75% drop in traffic, according to Dimitratou.

“How do you make sure that all the people that need you can find you? That’s what is so damaging about these laws. It will make it so difficult for people to find information,” Gomperts says. “When it’s illegal, nobody is there to give that information anymore and it becomes such a taboo. And that is internalized so that people are scared, and they don’t dare to talk about it anymore. And then information becomes much harder to find.”

A Google spokesperson told TIME that its algorithm changes are not designed to penalize or benefit any one site. “Our Search ranking systems are designed to return relevant results from the most reliable sources, and on critical topics related to health matters, we place an even greater emphasis on signals of reliability,” the spokesperson said. “We give site owners and content producers ample notice of relevant updates along with actionable guidance.”

In other countries where abortion is tightly restricted, including Poland and Saudi Arabia, Google does not allow abortion-related ads, and social media posts in some places are more limited too. It’s unclear how tech companies will handle ads in the U.S. if some states outlaw abortion entirely, as they’re widely expected to do.

A coalition of abortion rights groups and providers plans to meet at a digital rights conference in June to share strategies for navigating the complex world of social media policies and develop a list of improvements they would like to see from Big Tech companies. In the meantime, many groups are making an effort to reach people offline. Local abortion rights activists have held trainings on self-managing abortion for months. Last August, Plan C activists drove a truck around Texas with a mobile billboard advertising abortion pills, and this spring, the group paid for colorful ads on the New York City subway.

A new frontline: family doctors and others who don’t perform abortions

Dr. Chelsea Faso, a New York City-based family medicine physician who works with the nonprofit group Physicians for Reproductive Health, says there’s also a need to educate health care providers. Abortion, she says, should be treated no differently than other types of medical care. “Most family docs, like myself, provide care for folks from the cradle until they’re approaching the end of life,” Faso says. “When folks come in with a pregnancy, it really is our responsibility to be able to counsel that person on all of their options.”

Several organizations have taken the message to heart. Innovating Education in Reproductive Health, a program at the UCSF Bixby Center for Global and Reproductive Health, has launched a video series to educate providers in states where abortion is severely restricted on how to care for patients who self-manage their abortions.

Reproductive Health Education in Family Medicine (RHEDI) tries to spread that message early, by providing funding and support for family medicine residency programs that want to include abortion care in their curricula. Some “medical students are surprised to know that you can be a family medicine doc or a primary care doc and provide abortions,” says Erica Chong, RHEDI’s executive director. “That’s the first hurdle to get over.”

In 1997, a few years before the FDA approved mifepristone, about half of U.S. family medicine doctors surveyed by KFF said they were interested in offering the drug to patients. Decades later, only about 3% of early-career family doctors actually provide abortions, according to a 2020 study published in Family Medicine. Among that group, about 40% signaled that they provided only medication abortions, as opposed to procedural abortions.

Dr. Emily Godfrey, an abortion provider and family medicine physician at the University of Washington, says regulatory constraints are part of the problem. Even though it has repeatedly been shown to be safe, mifepristone is subject to the FDA’s Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies program, which places safeguards on drugs that regulators think pose potential risks. Under that program, providers have to register before they prescribe mifepristone, and that extra step can be a significant barrier, particularly for those who work in religiously affiliated health systems that do not provide abortion care, Godfrey says. More than 30 states also require a physician’s prescription, shrinking the provider pool to exclude nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and other clinicians.

Because mifepristone is closely regulated by the FDA, some providers are wary of offering it, says Ian Lague, the curriculum and program manager at RHEDI. “A lot of it is a confidence issue,” Lague says. “People feel that they need more training”—even when they’re perfectly qualified. Studies show the pills are 95% effective, and with a complication rate of less than 1%, they are safer than Tylenol or Viagra.

Legal requirements present another barrier. In Utah, for example, doctors are required to tell patients that medication abortion is reversible. Other laws, including ones in Texas and Oklahoma, also make anyone who aids an abortion liable to legal action, so “there’s a lot of fear to even talk about it or refer patients,” says Cindy Adam, CEO of the medication abortion provider Choix.

Some advocacy groups, including local abortion funds, are reminding doctors about their rights, and encouraging medical professionals not to report patients who may have had an abortion to the authorities. Even in states where people who enable an abortion can be legally vulnerable, doctors are not required to report patients to the police if they suspect they’ve taken abortion pills. “We have to, as a medical community, reinforce that fact,” Faso says. “There is no mandated reporting law for this and you are violating” patient privacy if you report someone.

Even with all of this knowledge and preparation, advocates and providers say it’s hard to predict exactly what they’ll see if Roe is overturned. Some Democrat-led states are making moves to protect abortion providers and increase funding for the procedure. The manufacturer of generic mifepristone is challenging Mississippi’s abortion pill restrictions in a case with a hearing scheduled June 8. Pitney, the Aid Access provider, says that medication abortion will likely reduce the number of people required to travel out of state to access abortions, but calls it a “Band-Aid on a much larger problem of access.” She predicts that unsafe abortion will increase if Roe is overturned, and that abortion providers, many of whom have been working on shoestring budgets for years, will struggle to offer services. “The abortion community was stretched thin prior to this,” Pitney says. “But the work is gonna get harder.”

Aid Access’s Gomperts says that so far U.S. laws have not prevented her from mailing pills to any state. But even if lawmakers double-down and do try to prevent her from serving the U.S., the existence of safe, effective abortion pills means that the genie is out of the bottle.

“They might be able to stop me, but that doesn’t mean that they will be able to stop medication abortion,” Gomperts says. “You cannot stop women accessing safe abortions with pills. They’re never going to stop that.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Abigail Abrams at abigail.abrams@time.com and Jamie Ducharme at jamie.ducharme@time.com