Growing up the child of two Auschwitz survivors, I was only mildly aware of my mother’s and father’s Holocaust experiences. Mum was an incredibly positive person. She managed to survive and live a fulfilling life despite the pain and mental stress of Auschwitz-Birkenau. My mother didn’t allow her experience to impact my sister and myself, and we grew up unburdened by the tragic times she lived through.

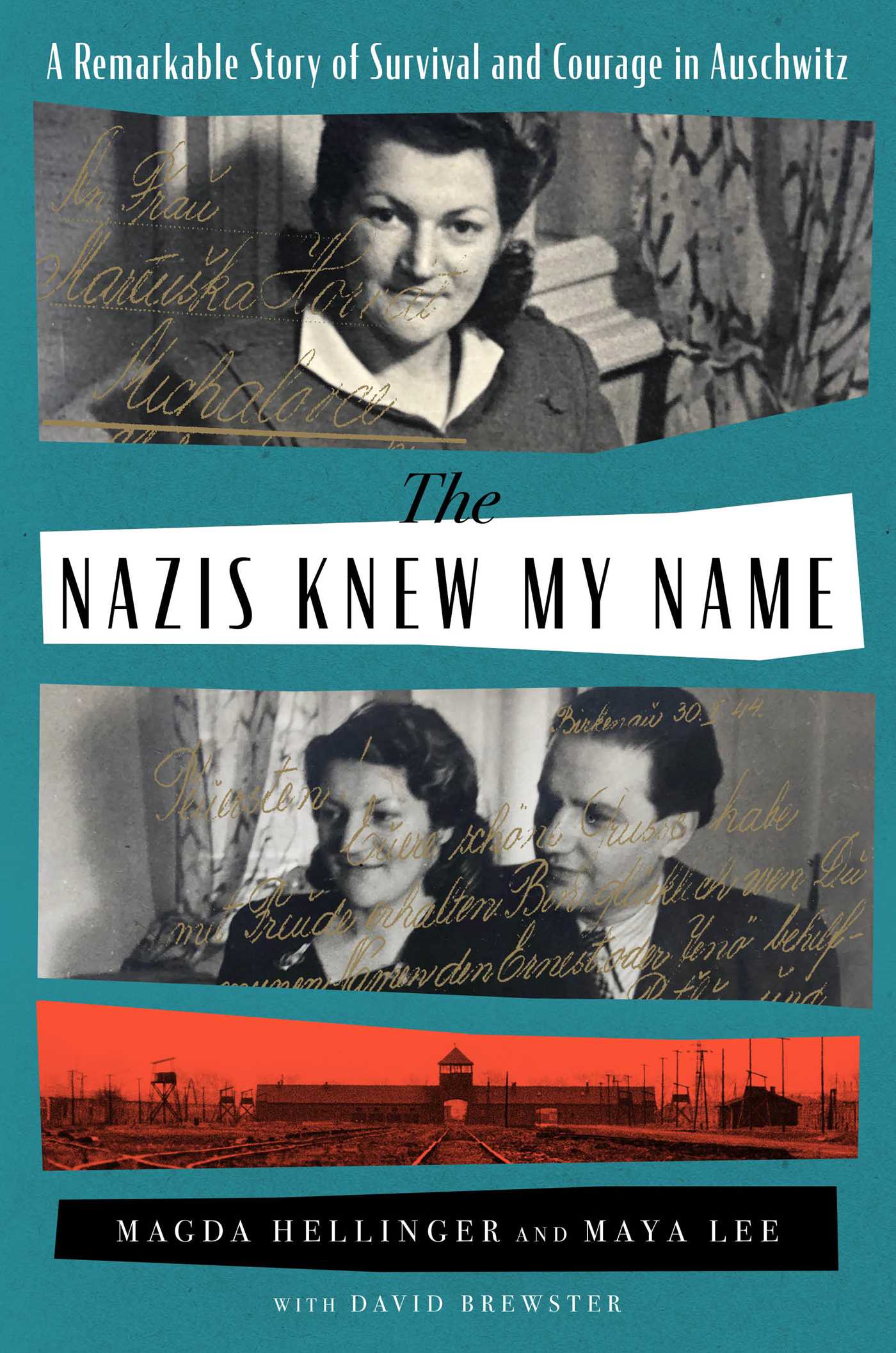

Which is not to say she didn’t try to tell us what she’d been through. Mum would sometimes talk to us about her experiences in Auschwitz, where, over the course of three and a half years, she served at various times in prisoner functionary roles such as Stubenältesten (room leaders), Blockältesten (block leaders) and Lagerältesten (camp leaders). The stories she would tell were mainly about how she was able to help save many lives using her position, but after a while, we just didn’t listen and said, “That’s O.K., Mum.” She did not think we were interested, so she did not pursue it further.

It was only later that I realized how much she wanted to tell her story—and how much of a difference that story could make.

Read more: How One Writer Uncovered the Lost Histories of 999 Women and Girls Who Were Sent to Auschwitz

After the war, the women who held functionary roles at Auschwitz were often perceived as Kapos, who were in charge of working labor groups within and outside the Auschwitz complex, notoriously known for their brutality and cruelty. And as one of the few survivors who were up close to the murderous, evil commanders and guards, my mother—who was anything but cruel—was often approached by historians, academics, teachers and writers. They wanted details and more information about what took place in the Auschwitz-Birknau concentration camp and the Nazis’ roles and actions within them.

After she passed away, I uncovered a box full of the letters and photocopies of her replies, in which she responded with detail. She told them how she often compromised her own safety to protect the women in her barracks, how she distracted the Nazis’ attention from the sick and vulnerable, how she successfully redirected women being led to the gas chambers, and how she was able to use her connections in the kitchen to smuggle extra food for the women struggling with malnutrition.

All this time, my mother thought these people would tell her story. However, each time, she realized they weren’t writing about her. They simply used her information for their own research.

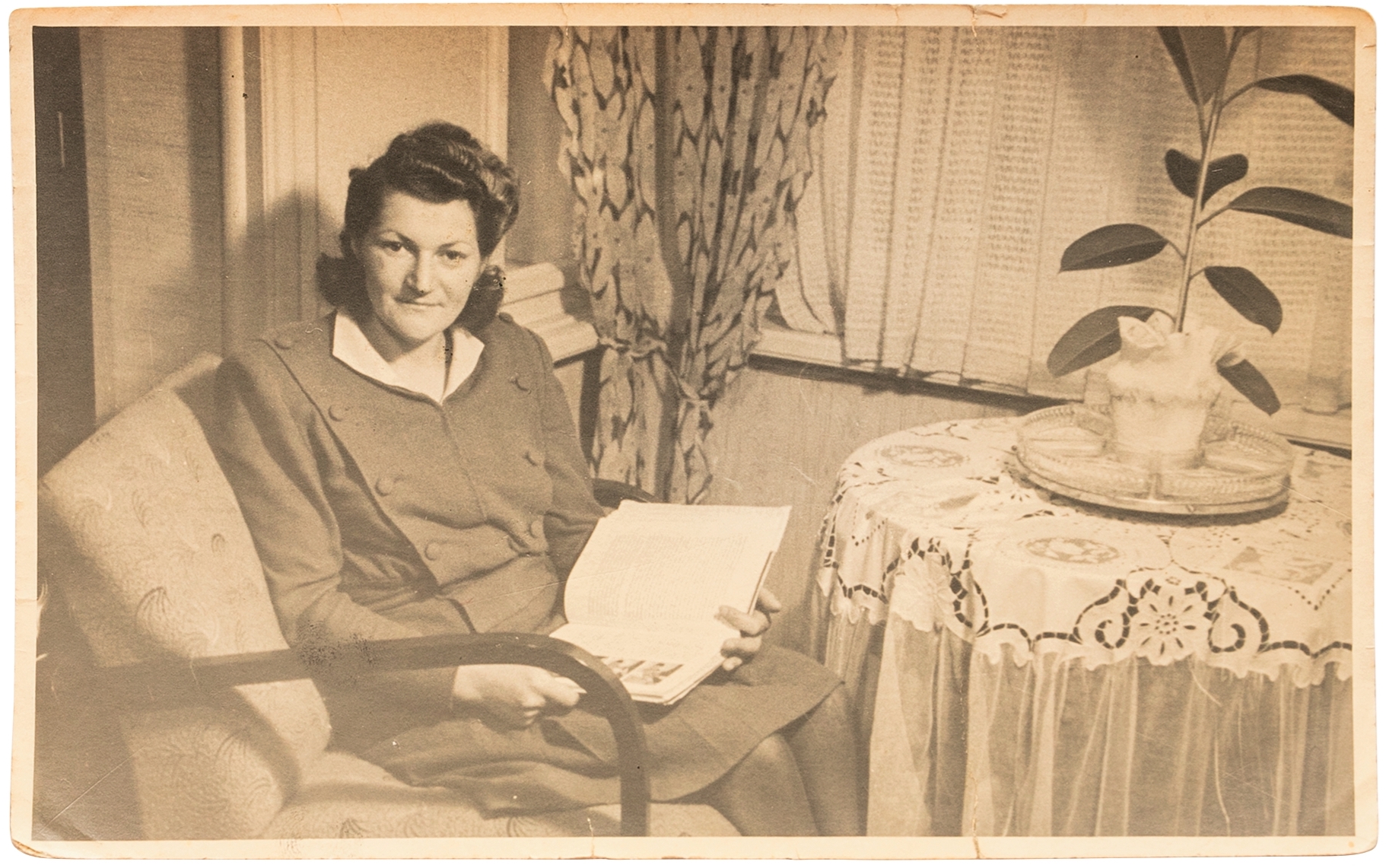

Unbeknownst to the rest of the family or me, she decided to write her own story. She had previously provided video testimonies to Yad Vashem in Jerusalem; the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C.; the Melbourne Jewish Holocaust Centre; and the Shoah Foundation. Then, by 2002, when she was 86, she began writing and rewriting her story by hand. The following year she took the manuscript to be transcribed and printed into a small book. She launched this project herself, sold a few books, donated the money to a charity she was connected to, and that was that! It was as if by writing her memoir, she no longer had to relive her trauma.

This is where my journey began.

In 2014, I received a call from a stranger living in Perth, Western Australia, who had seen my mother’s testimony on YouTube and was an admirer of her unique story. When I sent him my mother’s original memoir, he brought my attention to a mistake in the text. My mother referenced a newspaper article that was said to be in the book when, in fact, it wasn’t. I knew exactly which article he was talking about.

Read more: Why Auschwitz Plays Such a Central Role in Holocaust Remembrance

The article my mother referred to was by a New York gynecologist, Dr. Gisella Pearl, who had been a prisoner with my mother in Camp C. It was featured in the Israeli Hungarian-language Newspaper Új Kelet in August 1953. The headline read: ‘‘Magda the Lagerälteste of Camp C.” I knew my mother intended to include this article in her book, as I specifically remember her having it translated into English, but for whatever reason, it was left out. I decided to submit the book to a professional editor to have it reprinted, including the article. When the editor completed the manuscript, she told me that the story was incredible, but it lacked primary sources.

The material, however, was available. I started from that article, which provided a firsthand account of my mother’s role as prisoner functionary. I searched through other articles, as well as every letter and oral testimony Mum had done. I found testimonies from many survivors who were in Auschwitz-Birkenau with my mother and mentioned what she did for them and how she was able to save many of their families.

The result is more than just a personal account of the day-to-day life in Auschwitz-Birkenau, or a valuable counterpoint to the stereotypes about camp functionaries. It is also a window into human nature and the power of resilience and how one person can rise above the most horrific conditions, backed up by historical evidence. My mother’s role as Blockälteste and Lagerälteste allowed her to assist many women and help them to survive. During my research I was amazed to find that she had no doubt about what she was able to do in the camp. She did not allow fear to dominate her existence, however, she wrote, “Occasionally in a quiet moment I found myself reflecting on the times I had found the chutzpah and courage to speak up to the SS.” She remained human in the most inhumane place on earth, Auschwitz-Birkenau.

My mother always walked a fine line between following the orders of the Nazis while helping as many women as possible. She couldn’t save everybody, but she did the best she could. In finishing the project she began, I am sharing the story she wanted to share with the world— a story that, at a time when denialism and anti-Semitism is rising again, is still just as crucial as it was when she tried to tell it all those years ago.

Maya Lee, a co-author of The Nazis Knew My Name: A Remarkable Story of Survival and Courage in Auschwitz, is the daughter of Magda Hellinger.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com