At least 19 states passed 34 laws restricting access to voting in 2021, according to the Brennan Center for Justice. In Georgia, Gov. Brian Kemp signed a law limiting the number of drop boxes for ballots; in Texas, Gov. Greg Abbott signed a law banning 24-hour and drive-thru voting.

The laws came after record turnout in the 2020 election, including among African-American voters—and the Brennan Center’s research shows that the voter restrictions nationwide are more likely to impact African-American voters and minority voters.

Historians say that this wave of laws making it harder to vote echo the backlash to the electoral gains made by African Americans during Reconstruction (1865-1877), the era of political revolution in the aftermath of the Civil War. The above video looks back at Black politicians who served at all levels of government about a century before the 1960s civil rights movement.

“I think one of the reasons that it’s so timely to learn about Black political leaders during Reconstruction is because we have an unprecedented wave of new laws that are meant to suppress voters—specifically African-American voters—in some cases in order to ensure that African-American voices are not adequately heard in the political process,” says William Sturkey, associate professor of History at the University of North Carolina.

“Reconstruction was the first time that this country tried to be an interracial democracy—or a democracy, in other words,” says Eric Foner, Pulitzer Prize-winning historian and expert on Reconstruction. “It was the first time that African-American men… became part of the body politic, voted, held office. And key issues that are on our agenda today were fought out for the first time in Reconstruction.”

In 1867, Congress passed the Reconstruction Acts, requiring new state governments to be set up based on universal suffrage in states that were part of the Confederate States of America during the Civil War. New elections took place in 1867 and 1868. States like Mississippi, Alabama, and South Carolina were, at the time, close to a majority Black and elected Black men to statehouses and local positions for the first time.

“When African Americans were prevented from voting, federal troops or federal investigators would often be called in in order to protect [their] rights in order to cast the ballot,” says Sturkey.

Read more: Schools Are Failing to Teach Reconstruction, Report Says

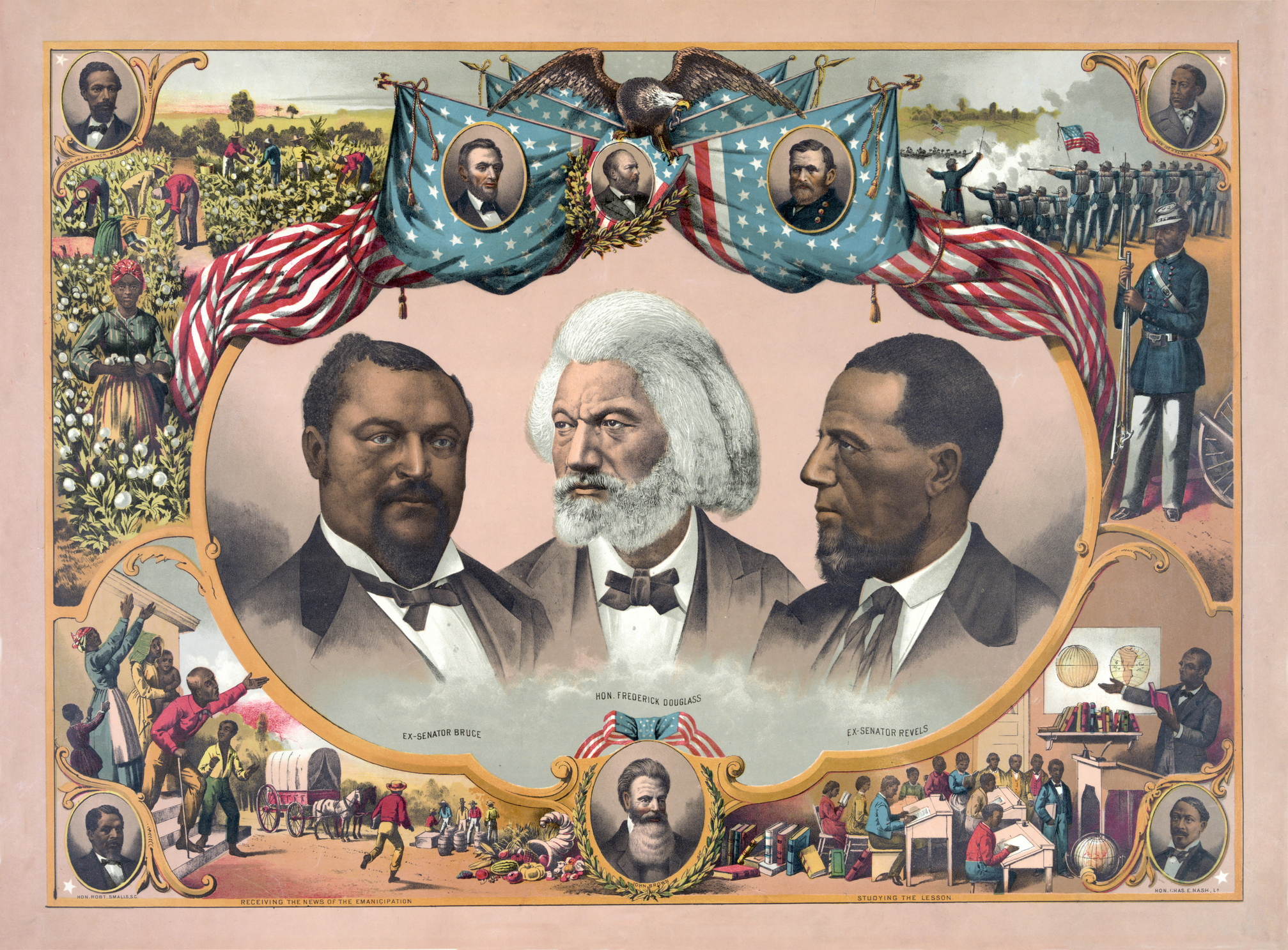

Foner, the author of Freedom’s Lawmakers: A Directory of Black Officeholders During Reconstruction, estimates that about 2,000 Black Americans held public office at the local, state, and federal levels during Reconstruction. Among the notable Black officeholders in this era: Republican Hiram Revels of Mississippi, the first Black U.S. Senator, appointed by the Senate to fill a vacancy; Blanche K. Bruce, another Mississippi Republican who was the first Black U.S. Senator to serve a full term; Robert Smalls, who escaped enslavement and went on to serve five terms in the U.S. House of Representatives; and Jonathan Jasper Wright of South Carolina, the first state Supreme Court justice in the U.S.

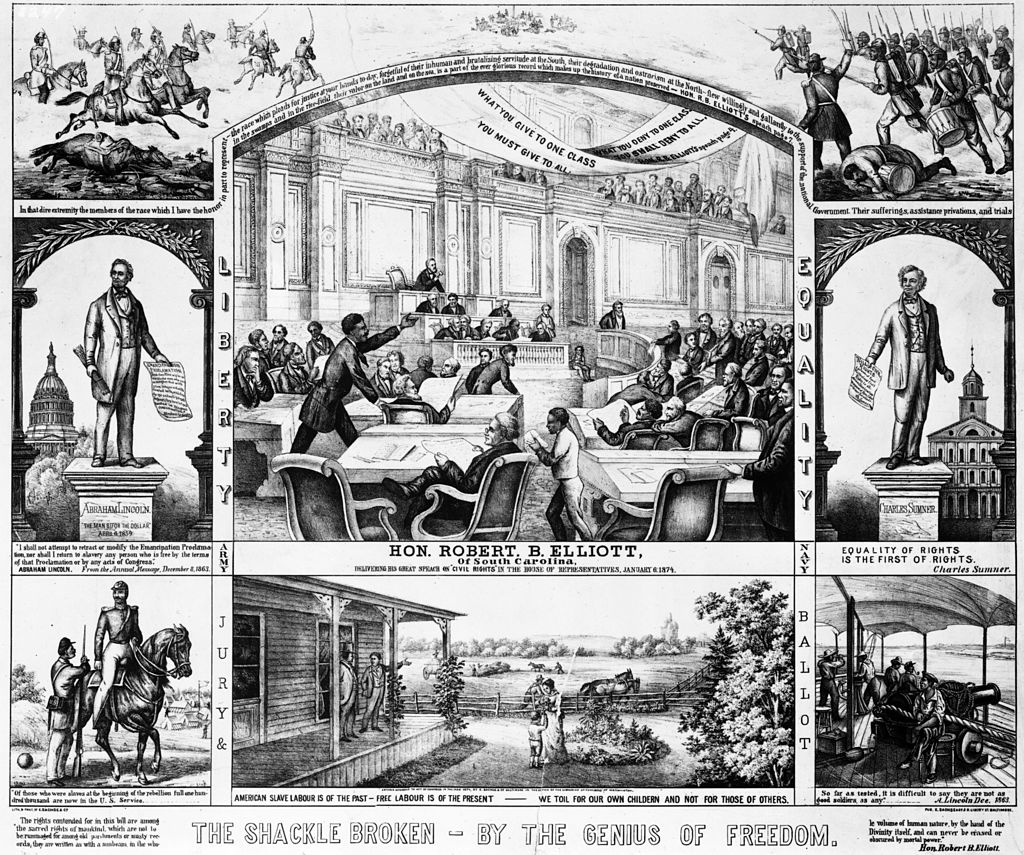

On Jan. 6, 1874, Robert B. Elliott, a Black Republican congressman from South Carolina, gave one of the most powerful speeches of the era in defense of what would become the Civil Rights Act of 1875. “What you give to one class you must give to all; what you deny to one class, you shall deny to all,” he said.

Historians say one of Black officeholders’ biggest contribution was their role in establishing state-sponsored public schools. Black lawmakers made up a majority of delegates at the 1868 South Carolina constitutional convention, which greenlit tax-funded public schools. Similarly, half of the delegates were Black at the Louisiana constitutional convention, which wrote integrated public schools into the new state Constitution. (Though most of the schools remained segregated.)

“The southern states were required to write new constitutions by the Reconstruction Acts of 1867… that allow Black and white men to vote and hold office. These new constitutions [also] included provisions for public education systems in the South,” says Foner. “Black officeholders played a key role in the creation of public education in the South.”

But Black officeholder numbers started to decline after 1877. As part of a deal to settle the contested 1876 presidential election, Ohio Gov. Rutherford B. Hayes won the presidency in exchange for the removal of federal troops in the South that had helped protect Black voters. In subsequent elections, Ku Klux Klan and vigilante violence at poll stations drove Black Americans away from the ballot boxes. Some Reconstruction state governments were overthrown, and the new state governments passed restrictive voting laws in what became known as the Jim Crow era. While the 15th Amendment of the Constitution said states couldn’t restrict voting based on race, state legislators passed laws that mandated expensive poll taxes (fees to vote) and literacy tests (questions with no right answers)—and subjected African Americans to them more than white Americans.

It wasn’t until nearly a century later when the 1965 Voting Rights Act made literacy tests and poll taxes illegal.

Read more: How Reconstruction Still Shapes American Racism

One reason the Black political leaders of Reconstruction aren’t often taught in U.S. K-12 schools is because the backlash to the Black officeholders during Reconstruction contradicts the narrative that America has improved with each generation, Sturkey says.

“It’s a little bit tricky to teach Reconstruction because African Americans during Reconstruction could vote in much of the South, and then things actually got a lot worse. It doesn’t really fit into this narrative of constant progress throughout America since the Civil War,” says Sturkey. “I think that a lot of people don’t realize that Black people actually could vote for a period of time and had lost it again and then had to fight for it again during the Civil Rights movement.”

Foner says Black political leadership provides a fuller picture of the diverse range of change-makers in the United States. The stories of Black officeholders during Reconstruction, he says, are important “for students of all backgrounds to understand that African Americans have always played a crucial role in American history.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com and Video by Arpita Aneja at arpita.aneja@time.com