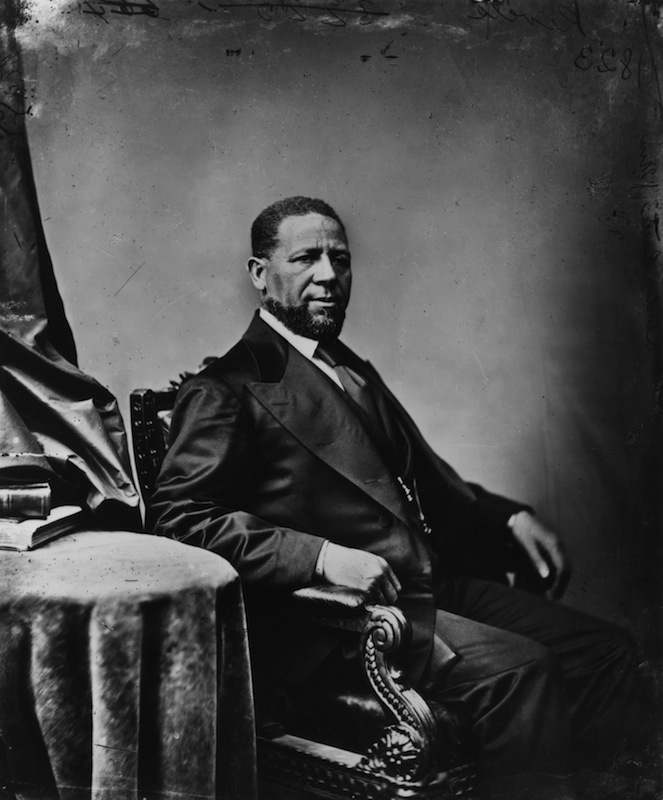

Hiram Rhodes Revels was a rising star of the Republican Party in 1869. A gifted orator — a skill he’d honed in his pre-political career as a minister — he’d just won a seat in the Mississippi state senate when he delivered an opening prayer so moving it left the statehouse awestruck.

“That prayer, one of the most impressive and eloquent prayers that had ever been delivered in the Senate Chamber, made Revels a United States Senator,” Revels’ fellow Mississippi legislator, John R. Lynch, later wrote. “It impressed those who heard it that Revels was not only a man of great natural ability but that he was also a man of superior attainments.”

So why, when Revels was chosen the following year to fill one of Mississippi’s two empty seats in the U.S. Senate, did his appointment raise the ruckus that would land him on TIME’s top-ten list of contested officeholders? Because some Democrats argued that since the 14th Amendment, which granted citizenship to people of color (including recently-freed slaves), had been ratified in 1868, Revels had only technically been a citizen for two years — not long enough to meet the Senate’s requirements.

Their argument was quashed, and on this day, Feb. 25, 1870, Revels became America’s first black Senator, serving out the unexpired term in a Senate seat that had been vacated when Mississippi seceded from the Union. The state’s other seat had formerly been occupied by Confederate President Jefferson Davis.

The irony of that reversal wasn’t lost on Revels’ Senate colleagues, including Nevada Senator James Nye.

“[Jefferson Davis] went out to establish a government whose cornerstone should be the oppression and perpetual enslavement of a race because their skin differed in color from his,” Nye declared on the Senate floor. “Sir, what a magnificent spectacle of retributive justice is witnessed here today! In the place of that proud, defiant man, who marched out to trample under foot the Constitution and the laws of the country he had sworn to support, comes back one of that humble race whom he would have enslaved forever to take and occupy his seat upon this floor.”

While Revels might have taken issue with his characterization as a member of “that humble race,” he apparently didn’t mention it publicly. His time in office was marked by moderation and forgiveness. He was a staunch advocate for granting amnesty to former Confederates, provided they swore an oath of loyalty to the Union, and he spoke out against segregation, believing it only perpetuated prejudice.

“I find that the prejudice in this country to color is very great, and I sometimes fear that it is on the increase,” he said in one floor speech. Amid the tensions of the Reconstruction Era, he attempted to soothe the fears of his fellow politicians. In an argument for educating freed slaves, he promised, “The colored race can be built up and assisted … in acquiring property, in becoming intelligent, valuable, useful citizens, without one hair upon the head of any white man being harmed.”

Read a 1967 story about Edward William Brooke III, the first African American senator elected after the ratification of the 17th Amendment, here in the TIME Vault: An Individual Who Happens To Be a Negro

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com