There is a question that is asked of all stand-up comics. And it is asked most frequently of comics who are being newly discovered by the press. It is seen as the perfect way to really get to know the comedian: “Who were your favorite stand-up comics when you were growing up?”

It’s a simple question. But when the press was first discovering me in the early 2010s, it felt really complicated, because the stand-up comic I loved the most growing up was Bill Cosby. He had been a part of my entire life, from his cartoon Fat Albert and The Cosby Kids in the ’70s to his stand-up, and of course through The Cosby Show in the ’80s. For my high school graduation I wore a “Cosby sweater” instead of a suit jacket.

But when major media first took interest in me following the premiere of my FX show Totally Biased, there were already stories of women accusing Bill Cosby of sexual assault. They weren’t getting much traction in the press—and wouldn’t until several years later when the #MeToo movement ignited in full force—but it was enough that I couldn’t just say his name without reservation. On the other hand, if I didn’t say that I had loved Bill Cosby, I would be lying. And I would also look like the one Black kid who grew up in the ’70s and ’80s who didn’t like Bill Cosby.

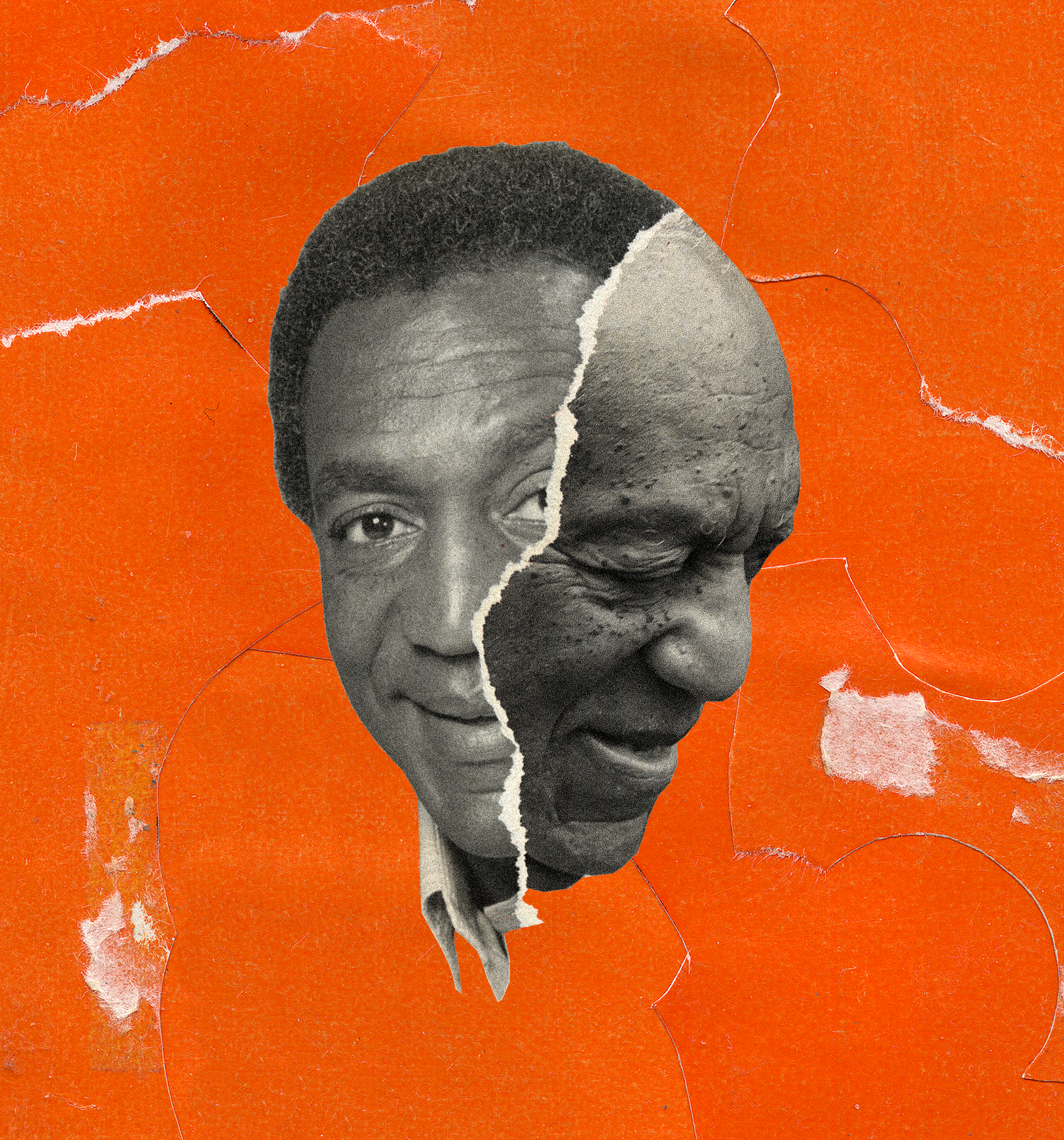

So I tried to get clever with it. I would mention other comics and at the end I’d say, “and the artist formerly known as Bill Cosby.” It was my way of telling the truth but also acknowledging that there was something else going on that I couldn’t ignore. The interviewer always seemed to get this and move on to other questions. But it left a bigger question in my mind that has only grown since then: How do we talk about Bill Cosby? How do we do it in a way that is honest to our own personal experiences and acknowledges the experiences of others? How do we hold these incredibly divergent truths? The gap from “my hero” to “my rapist” is unfathomable. But we have to try. I try to start to reckon with all this in the four-part docuseries I directed, We Need To Talk About Cosby, which premieres at the Sundance Film Festival before coming to Showtime on Jan. 30.

I think the first tape I ever rented from a video store was the stand-up comedy special Bill Cosby: Himself. It was the early ’80s, I was 10 or 11, and I was already falling in love with comedy. Before the Internet, the only way you could watch comedians was to stay up late to watch The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson or Saturday Night Live. So when video stores opened and I discovered that I could just rent a tape and watch comedy whenever I wanted to, it felt like magic. The other tape I rented was Eddie Murphy’s comedy special Delirious, although because of his R-rated reputation, I had to get my mom’s permission for that one.

But I didn’t need my mom’s permission to watch Bill Cosby. She knew that one would be family-friendly. By the time Himself came out, Bill Cosby had more than 20 years in the spotlight as a G-rated comedian. And more than just being a clean comic, Cosby was already known as someone whose content was not only good to listen to but also good for you. Even more relevant to Black folks, he was someone to look up to at times when we needed heroes the most. Bill Cosby was someone who had his hand extended to pull you up with him. When I watched him—especially on his shows aimed at kids like Fat Albert, Picture Pages and The Electric Company—I saw a Black man who wanted me to be smart, like he was. He wanted me to be successful, like he was. He wanted me to be a good person, like I thought he was.

Throughout his career, Bill Cosby was the kind of Black entertainer Black folks were happy to support. He was successful without “bowing or scraping” or “shucking and jiving,” as it was called back then. And though he was loved and celebrated by white folks, he didn’t lose himself in the process. He was beloved by white America at a time when other Black folks were getting beaten up by police every night on the news. In the 1960s, when Martin Luther King Jr. was advocating for a world where Black and white could live together, Cosby was doing his part to make that a reality by integrating TV and night clubs. Martin Luther King Jr. was being called uppity and under constant threat. Cosby was accepting Emmys and Grammys by the handful. And what most of us didn’t know is that some of his most important work was being done behind the scenes. He revolutionized the stunt industry for Black performers by insisting his stunts be done by a Black man and not by a white man who was painted black. (Yes, that was a thing.) Cosby made sure to hire Black people behind the scenes before we all understood how important that is.

I didn’t know all that when I was a kid. So much of the Bill Cosby story for me is about what I didn’t know then, and what I do know now. I also didn’t know that if you go all the way back to the early years of his career, there are women who have accused him of sexual assault or rape. These allegations are consistent throughout his career. When you look into the stories of the more than 60 women who have come forward, you see all kinds of women, of different races and backgrounds. Some who knew him for one night and some who knew him for years. Some worked for him. Some looked at him as a mentor. Some only sort of knew who he was when they met him. The only common thread they have is their stories of Bill Cosby assaulting or raping them. Admittedly, I didn’t look deeply into their stories until I worked on this project. My “artist formerly known as Bill Cosby” thing feels especially feckless and mealymouthed now.

When Bill Cosby was sentenced to prison, I thought, “Well, the story is over now. He’s 81, maybe now is the time to talk about all this.” I started working on the docuseries in 2019. I reached out to the comedians I knew had a stake in the conversation. That list is pretty much every comedian I knew, and maybe even every comedian, period. I quickly found out that I was among the few who wanted to have the Bill Cosby conversation. Very few of the people who worked with him wanted to talk, either. And of course since this is about Bill Cosby, many of these people who didn’t want to talk are Black. This is a third-rail conversation for Black folks. Whether you believe the women, whether you think Cosby is (or ever was) a hero, there are too many land mines. This is combined with the fact that no matter what you think about Cosby, Black folks in the U.S. are always living under a deficit of role models and representation. Consider all that alongside the fact that America has a well-earned reputation for criminalizing and killing innocent Black men. There is no perceived gain in taking a Black man down.

I wondered if I was making a mistake taking this on. (I have wondered that many, many times, even as I type this.) Then COVID-19 hit, making production impossible. And then on our last day of filming, in June 2021, the crew and I were in Philadelphia, waiting for our last interviewee to arrive, when I got a text message from a friend: “Your film just got way more interesting.” Bill Cosby was being released from prison, less than an hour’s drive from where we were. I’m sure that everybody who had said no to me before this moment breathed a sigh of relief. The third-rail conversation had just gotten another shot of electricity.

This docuseries feels like it could be the end of my career. Many times while making it I hoped it would just go away. Get canceled or permanently shelved. It had certainly happened to other Bill Cosby documentaries. But then every time I would have that thought, I would think about the women who have alleged harrowing encounters with Cosby and their bravery when they talked to me for this project. These are women who have gone through the ringer since they came forward. Lili Bernard, who claims Cosby drugged and raped her during the time she appeared on The Cosby Show, says there has been constant “blaming and shaming.” Most of these women have learned to distrust the media as a whole. But they trusted me with their stories. I couldn’t leave them on the shelf, even if my career is in the balance. We have to be able to at least have the conversation. So much more is at stake.

This is bigger than Bill Cosby. America has a reputation for not listening to women who have been sexually assaulted. America has a history of allowing powerful men to take women as the spoils of their power. America has done an awful job of dealing with racism and rape. I sincerely hope that we can do a better job of dealing with both those issues in the Bill Cosby conversation. I believe there is one more thing to learn from him, whether he wants us to or not.

Bell is an Emmy-winning producer, stand-up comedian and host of CNN’s United Shades of America

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com