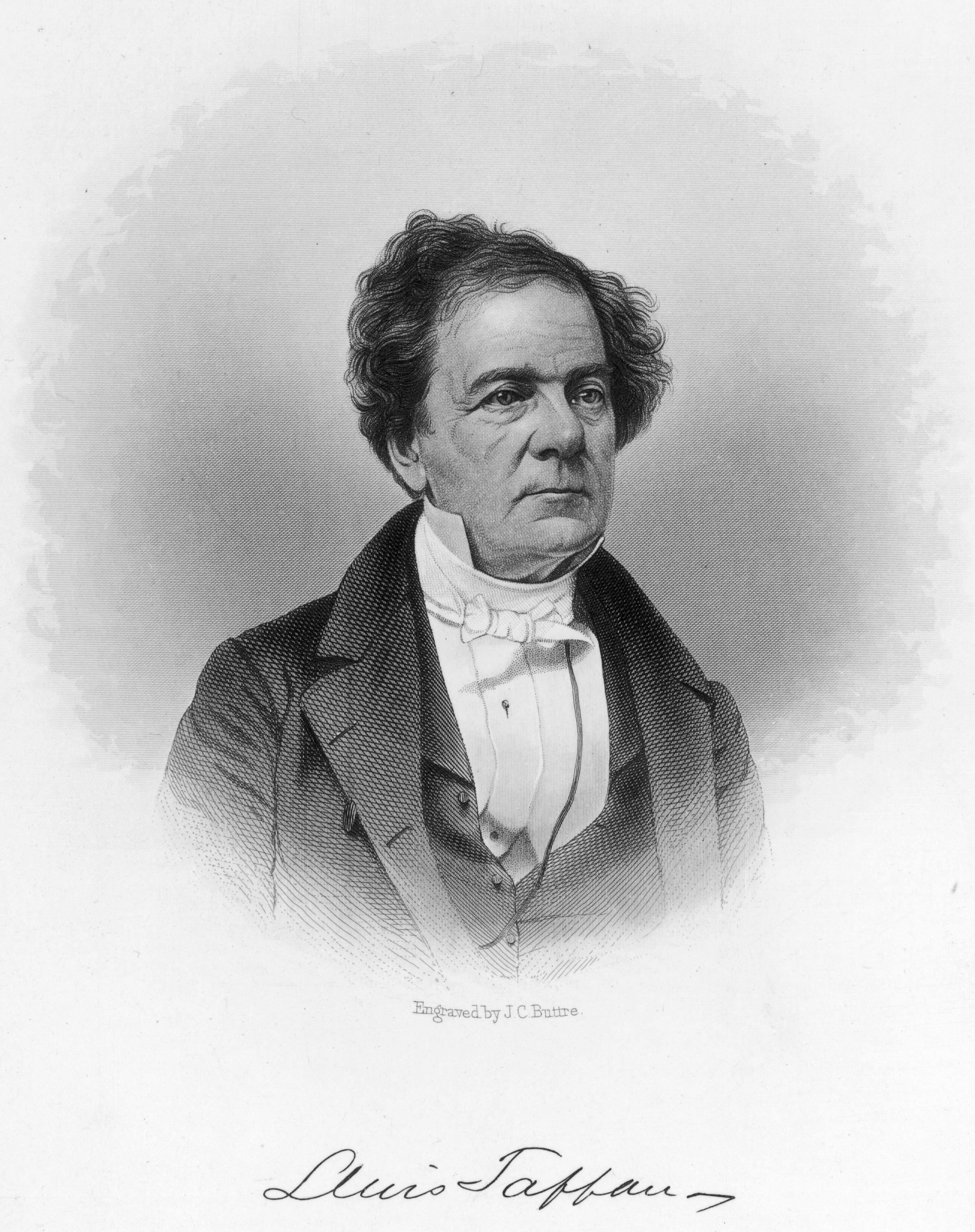

Abolition in America stood at a crossroads in the mid-1830s. Reviled in the national press, denounced by demagogues, and attacked by mobs, abolitionists faced unprecedented hostility and violence coordinated by Southerners and their sympathizers in the North. In this climate, the silk merchants Arthur and Lewis Tappan—who provided the financial muscle behind abolition in the Northeast and had helped bring it to prominence through the recently formed American Anti-Slavery Society— realized the anti-slavery movement needed a new direction. They couldn’t use bricks and bludgeons like their enemies did, but they could use words potentially as fearsome as any weapons.

They had to act quickly. To be sure, the great majority of Americans still disapproved of the movement, but, as more people read about abolitionists and what they stood for, a small but growing minority found it worth considering. In the last two years, hundreds of new anti-slavery groups had formed in the Northeast and out to the Great Lakes—from Augusta, Maine, to Windham, Ohio—run by men and women, Black and white, laity and clergy, moderates and radicals. These groups had been fueled by their abhorrence of plantation slavery; to maintain their momentum, Lewis Tappan needed to show them proof that abolition had gained traction, or at least attracted attention.

The secretary of the American Anti-Slavery Society, Elizur Wright, provided him with a tempting opportunity: for an economical cost, they could flood the South with pamphlets and newspapers against slavery, inciting a reaction that would generate publicity and spread the word of abolition further than it had ever gone. Lewis endorsed the plan, but he knew the Society’s publications would have to be more readable and compelling to succeed. So he took over as the chairman of publications, revamped the newspapers, and targeted new recipients. Lewis set a goal of raising $30,000 to fund a national distribution plan—to send them to every corner of the United States, but especially the South, by printing 25,000 to 50,000 copies a week. The Society set about raising the money for the campaign and enlisting volunteers to research the names and addresses of potential recipients: politicians, ministers, businessmen, and other key figures.

Read more: The $60,000 Telegram That Helped Abraham Lincoln Abolish Slavery

Through his earlier experience with printing evangelical tracts, Lewis knew something about mass distribution, so he employed cheap steam-press printing and the national network of the U.S. postal system to send 175,000 copies of materials out of New York alone over a period of 5 weeks in the late summer of 1835. The Society sent off more than a million pieces of mail for the four publications, making it the largest persuasion campaign abolitionists had ever mounted.

The publications were visually striking, filled with stories and images that illustrated the depravity and cruelty of the plantation system. They aimed to provoke readers into taking a stand on what they read. Even the periodical The Slave’s Friend, aimed at children, used images of Black people in chains being whipped and abused.

Lewis knew the mailings would be explosive, but he saw them as a way for abolitionists to take the offensive against their opponents. Such words and images would feature rhetoric in the style of William Lloyd Garrison’s groundbreaking newspaper The Liberator, but aimed at a much bigger audience. By taking the risk of sending out such material, Lewis outdid even the most brazen column Garrison had ever written, and he provoked a reaction in the South far greater than any abolitionist ever had.

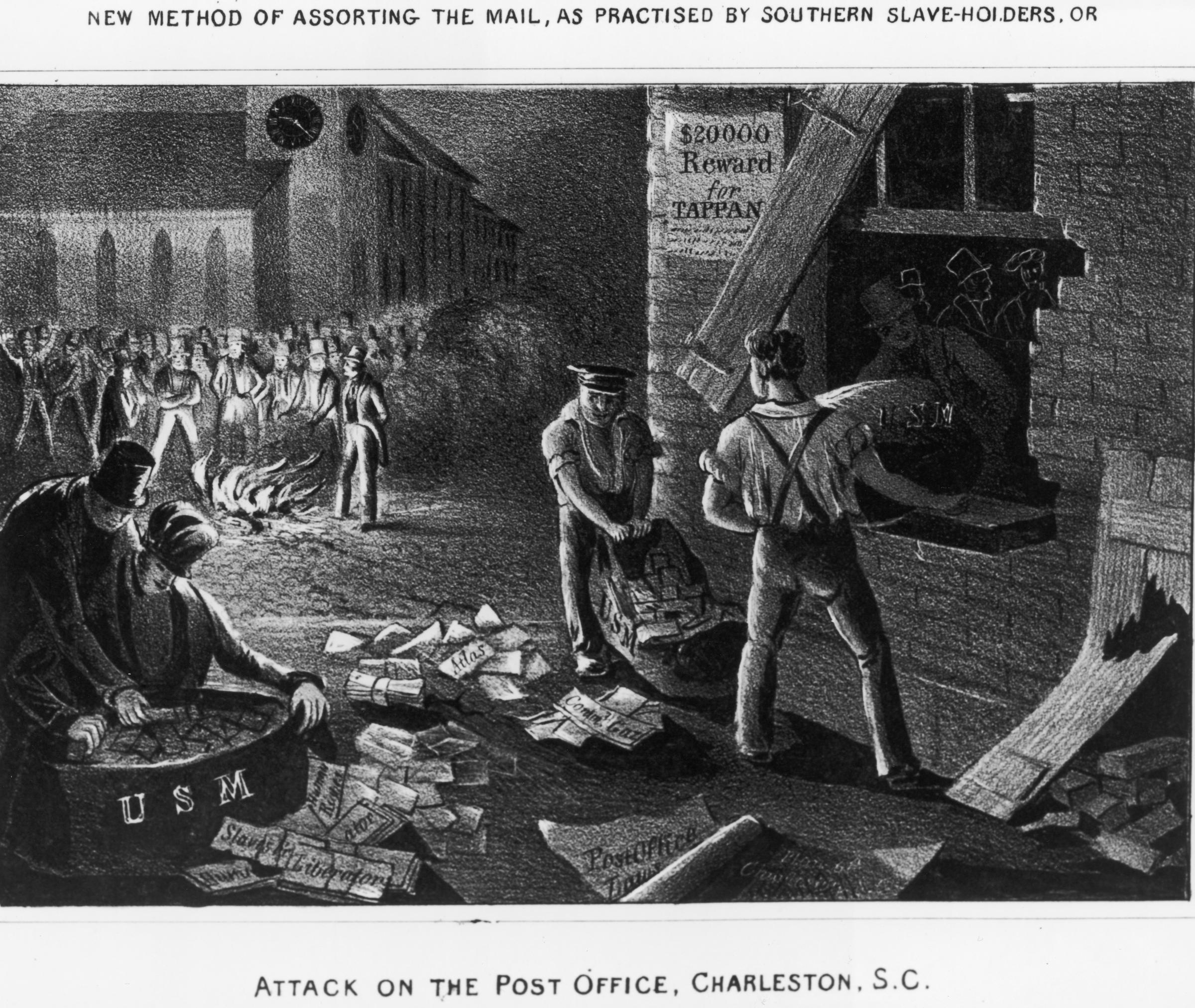

The steamship Columbia arrived in Charleston on the night of July 29, bearing mailbags loaded with pamphlets sent by the American Anti-Slavery Society. They were conveyed to the post office, after which the locals, having heard news of the delivery, intercepted them. They broke in through a window and carried off all the mail they could grab. The next day the white town folk held a meeting and, with their clergy’s blessing, resolved to burn all mail concerning abolition. They rifled through the sacks picking out newspapers that looked suspicious and gathered to dispose of them that night.

When darkness fell, three thousand Charlestonians assembled at the parade ground and threw a bonfire to incinerate the literature. It was a festive affair, with a balloon ascending to the sky and effigies of infamous abolitionists to burn along with the newspapers below their feet. The city council justified the destruction of newspapers by claiming they “would be likely to produce incalculable evil” if people could read them and begin to question the slave-labor system the region was built upon.

A former governor and four other men soon formed a committee to inspect steamships for offending literature arriving into South Carolina, and reserving the right to burn whatever they found objectionable. In response, the Charleston postmaster asked the postmaster general, Amos Kendall, what he should do. Kendall told him to use his own judgment, because “We owe an obligation to the laws, but we owe a higher one to the communities in which we live.” In other words, censoring the mail might just be necessary.

Also following the riot, reports begun appearing in the Southern press claiming that the abolition papers were turning up everywhere—in Mobile, Alabama, at a post office; trundled into Virginia by an antislavery agent; received en masse in Savannah; found along a roadside in Enfield, North Carolina. In response, vigilance committees formed to suppress the mail, to track down stray copies of the material, and to threaten those who possessed it. Those suspected of sympathizing with abolition were publicly defamed, put on trial, or expelled from their communities—even jailed, assaulted, or murdered. Torchlight parades and protest meetings erupted with demagogues decrying the propaganda from the North and vowing to prosecute those who had sent it. The vigilance committees, with virtually unlimited power outside of the law, swept into the quarters of Black citizens, charging them as potential accomplices, and hunted through post offices, stagecoaches, and steamships for evidence of sedition. Several white people found guilty of “association with Negroes” were executed in South Carolina and Georgia.

Increasingly fanciful conspiracy theories credited Northern abolitionists with powers far beyond their means, from seeding the South with agents to inspire slave revolts to secretly preparing the ground for civil war. Politicians claimed enslaved Black people had received and read the literature to plot insurrections; planters, ministers, and common workers held mass meetings at which they vented their hatred of interlopers who dared to question slavery. They launched into diatribes about white Southerners’ supposed constitutional right to own Black human beings, and biblical justifications for slavery. They vowed to take the fight to the North and demand that governors and legislatures censor any literature that offended the South.

Read more: Slavery Still Exists All Around the World. Here’s How Some Countries Are Trying to Change That

The Southern press said that Lewis and Arthur Tappan were capable of causing havoc anywhere, at any time, and lay in wait to strike with cold-blooded cunning. Bounties were offered, including one from a Norfolk rally that promised $50,000 for Arthur’s delivery to Virginia, dead or alive. A state grand jury indicted the entire membership of the American Anti-Slavery Society, with hopes of seeing them extradited to receive their punishment. Rumors of a pilot boat from Savannah waiting in New York Harbor to kidnap Arthur and other abolitionists frightened some activists, with his fellow abolitionist Lydia Child writing of assassins lurking in the city to stab him, “like the times of the French Revolution, when no man dared trust his neighbor.” In the pages of the Courier and Enquirer, the editor James Watson Webb warned of civil war, “with all its kindred horrors of rape, sack, and slaughter.”

Southern businessmen took action to boycott Arthur Tappan and Company, refusing to buy products from the notorious friend of Black people. The boycott expanded from South Carolina to Tennessee and Virginia, with pressure groups demanding Southerners stop buying or importing their delicate parasols, gloves, hats, and other niceties from such “fanatics,” admonishing fellow citizens that, “It is you who have enriched these miscreants.”

Scores of bankers and merchants on Pearl and Wall Streets began to fear the reprisals. They urged the Tappans to tamp down their support for abolition, lest the entire trading economy of New York suffer. But Arthur was unswayed, since his brother’s bold publishing gambit had made national headlines and drawn more attention to the cause than it had ever received. He answered his critics with uncharacteristic fury: “You demand that I shall cease my anti-slavery labors, give up my connection with the Anti-Slavery Society, or make some apology or recantation—I will be hung first!”

Lewis Tappan spoke more peaceably but just as defiantly. In a letter to a South Carolina Vigilance Committee, he wrote, “We will persevere, come life or death, if any fall by the hand of violence, others will continue the blessed work.”

Adapted from The Republic of Violence: The Tormented Rise of Abolition in Andrew Jackson’s America by J. D. Dickey. Copyright © 2022. Available from Pegasus Books.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- L.A. Fires Show Reality of 1.5°C of Warming

- Behind the Scenes of The White Lotus Season Three

- How Trump 2.0 Is Already Sowing Confusion

- Elizabeth Warren’s Plan for How Musk Can Cut $2 Trillion

- Why, Exactly, Is Alcohol So Bad for You?

- How Emilia Pérez Became a Divisive Oscar Frontrunner

- The Motivational Trick That Makes You Exercise Harder

- Zelensky’s Former Spokesperson: Ukraine Needs a Cease-Fire Now

Contact us at letters@time.com