This piece is part of an ongoing series on the unsung women of history. Read more here.

The thought of a woman abolitionist usually calls to mind a white woman speaking on behalf of enslaved African-Americans. But more than one figure in history challenges that whitewashed image of the movement to abolish slavery. Former slaves were often outspoken anti-slavery agitators—and so were black people born free in Northern, non-slave states.

One of those abolitionists, Maria Stewart, was one of her era’s most effective anti-slavery voices, breaking boundaries for women even as she advocated for an end to a brutal institution.

Born in 1803 in Connecticut, Maria Miller did spend time in bondage, but not as a slave. Rather, she became an indentured servant at age 5 when her parents died, leaving her a pauper. She served in the house of a minister for a decade, sneaking peeks at his library while she worked. When her ten years of service were over, she took advantage of New England’s “Sabbath schools”—free Sunday schools—to get even more education.

Maria married James Stewart when she was 23 years old, but when her husband died suddenly, his white executors deprived her of his estate. The lawsuit that followed left her impoverished again. This time, though, Stewart had an education to fall back on. Called to action by the prejudice she had witnessed in New England and moved by the plight of black slaves in the South, she began to write and lecture on behalf of racial justice.

But Stewart quickly ran up against not just anti-black sentiment, but societal restrictions on women. At the time, it was taboo for a woman to speak in public, and even more scandalous for a woman to do so in front of a group of men. Though women were expected to serve as a kind of moral conscience for their politically active male relatives, they were forbidden from doing so in public, and when women gathered to do good, they were expected to do so in same-sex groups only.

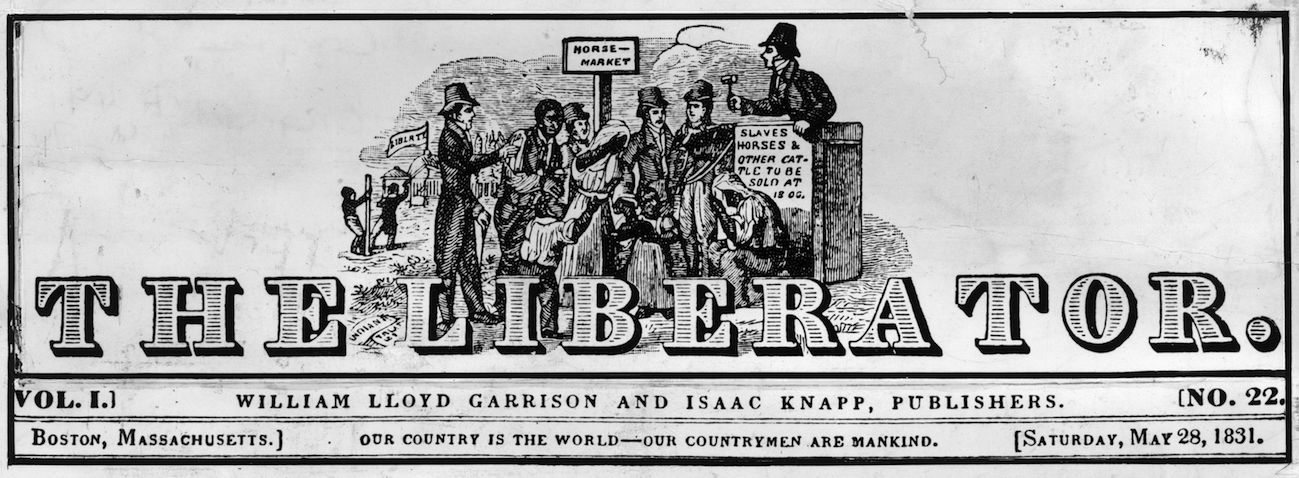

That frustrated activists like Stewart, who knew that direct appeals to voting men were the only way to effect political change on slavery. She found a powerful ally in William Lloyd Garrison, a legendary anti-slavery journalist who discovered her writing and encouraged her to speak freely about her views. Garrison encouraged other women to speak out, too—women like Frances Wright, a Scottish free-thinker who scandalized Americans in 1828 during the first public speaking tour ever put on by a woman. Why not put the tactics of women like Wright into action on behalf of the fight against slavery?

In 1832, Stewart gathered her courage and addressed a group of black women in Boston. Then, she gave a lecture to a group of women and men. She gave two other speeches that year—speeches that called Northerners to task for their bigotry against black women in particular. “I am also one of the wretched and miserable daughters of the descendants of fallen Africa,” she declared in one address. “Do you ask, why are you wretched and miserable? I reply, look at many of the most worthy and interesting of us doomed to spend our lives in gentlemen’s kitchens. Look at our young men, smart, active and energetic, with souls filled with ambitious fire; if they look forward, alas! what are their prospects?”

Stewart only gave four speeches, but they made an impression on both their audiences and her critics. Not only did her words constitute a powerful call to action, but they challenged assumptions that black people and women were illiterate, uneducated and ignorant. At least one account of Stewart’s speeches states that her black male audience jeered her off the stage and threw rotten tomatoes at her. In any case, Stewart felt so threatened by the reaction to her speeches that she no longer felt welcome in Boston; as Garrison put it, she “encountered an opposition even from her Boston circle of friends that would have damped the ardor of most women.” Shortly after her fourth, farewell address, she moved to New York.

Though Stewart was hounded by the consequences of her bold public speeches, she never gave up the fight against slavery. In New York, she befriended Frederick Douglass, attended anti-slavery conventions, wrote more anti-slavery articles, and taught black girls. During the Civil War, she moved to Washington and continued teaching, taking over a job as housekeeper at the Freedmen’s Hospital and Asylum that had previously been filled by one of the other great black women abolitionists, Sojourner Truth.

Not only did Stewart live to see the end of slavery, but she also obtained another kind of justice during her lifetime.

Forty-nine years after her husband’s death and her loss of his inheritance, she learned that a new law that finally granted financial assistance to the relatives of War of 1812 veterans meant she was eligible for a widow’s pension. She was one of about 25,000 people who made claims under the new law—and though she only received her pension for a year, it was a kind of triumph for a woman whose contributions were largely overlooked in her later years.

These days, few people remember Stewart’s brave speeches or her fiery condemnation of racial discrimination in an age known for its bigotry and intolerance. But her work deserves to stand next to that of more famous black abolitionists like Sojourner Truth and Harriet Tubman—and alongside other women like the Grimké sisters who dared to speak out in an era in which women were expected to remain silent.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Breaking Down the 2024 Election Calendar

- How Nayib Bukele’s ‘Iron Fist’ Has Transformed El Salvador

- What if Ultra-Processed Foods Aren’t as Bad as You Think?

- How Ukraine Beat Russia in the Battle of the Black Sea

- Long COVID Looks Different in Kids

- How Project 2025 Would Jeopardize Americans’ Health

- What a $129 Frying Pan Says About America’s Eating Habits

- The 32 Most Anticipated Books of Fall 2024

Contact us at letters@time.com