Elections brought significant changes in 2021: E.U. stalwart Angela Merkel ended her 16-year leadership of Germany, Chile elected a millennial socialist; and Hondurans chose their first female president. But in 2022 leadership of major states on every inhabited continent will be contested in the thick of two global crises: the COVID-19 pandemic and a climate catastrophe that grows more evident each week. And at least three democracies will decide the fate of leaders (or the kin of leaders) with distinctly authoritarian inclinations.

Here’s a roundup of the key elections in the year ahead, listed in their likely running order:

India

Although India’s general election is not until 2024, upcoming state assembly votes could define the future of the ruling Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). With over 200 million inhabitants, India’s most populous state Uttar Pradesh will head to the polls in early 2022. Home to the constituency of the right-wing populist Prime Minister Narenda Modi, the state is part of the Hindi Belt of northern India, and a key indicator of the BJP’s popularity.

Under Modi’s leadership, the BJP has engineered the othering of Muslims in the country, reopened religious wounds, and empowered Hindu supremacist groups. Uttar Pradesh’s farmers have been a driving force behind year-long protests which forced Modi to pledge in November to repeal divisive agricultural reform laws.

Modi had maintained that the laws—aimed at opening India’s agricultural markets to greater corporate participation—would have raised farmers’ incomes. Analysts say the Prime Minister’s rare apology suggests the BJP is anxious about the state assembly elections, which will inevitably be read as a mid-term referendum on Modi’s rule.

South Korea

South Korea’s election on March 9 will likely come down to whether voters still trust the Democratic Party after five years in power—despite corruption allegations and little in the way of progress on reconciling with North Korea.

South Korean president Moon Jae-in must step down after a single term in office, and Lee Jae-myung, the Democratic former governor of the province around Seoul, is vying to take his place. However, Lee trailed Yoon Seok-youl of the traditionally conservative People Power Party in a recent poll, 31% to 42%.

Yoon, the country’s former Prosecutor General, has said he’ll focus on strengthening the rule of law. Lee is campaigning on a promise to introduce a universal basic income. But accusations of corruption and abuse of power against both candidates are taking the focus away from their policies.

France

History has not been kind to sitting French presidents–only one since 1988 has survived a re-election campaign. Yet incumbent leader Emmanuel Macron so far tops the polls for the 2022 presidential election.

When he first stood for national election in 2017, the centrist saw off opponents from parties that had dominated French politics for decades. But so did the other run-off candidate, Marine Le Pen, who strived to make the far-right National Rally party more palatable to conservative voters.

Macron won in a landslide, and when France goes to the polls in April, two candidates will compete for the anti-EU, anti-immigrant vote: Le Pen, and former TV commentator Eric Zemmour. Nicknamed the “French Trump,” Zemmour said he’s running “so that our daughters don’t have to wear headscarves and our sons don’t have to be submissive”.

The major challenger may be Valérie Pécresse of the conservative Les Républicains party. A recent Ipsos/Sopra Steria poll named her the likeliest to face Macron in a run-off, required under French law if no candidate wins a majority in the first round.

Whoever the opponent, Macron faces a tough fight. The former investment banker is viewed as elitist by some—having cut taxes on the wealthy, and proposing a fuel tax hike that sparked protests by tens of thousands of lower income workers in 2018. He is also boldly pro-E.U., and the union’s most prominent power broker with the departure of Merkel. Like other centrist world leaders fighting off “demagoguery”, Macron is banking that voters’ desire for pragmatism will lead him to a second five-year term.

Parliamentary elections in April will likely either push Hungary closer to authoritarianism or pull it back from the brink.

During his nearly 12 years as Prime Minister, Viktor Orbán has transformed the Eastern European nation of 10 million into a self-styled “illiberal democracy,” curtailing press freedom, eroding judicial independence, and introducing a raft of socially restrictive measures, including a recent ban on material seen to be promoting homosexuality. The E.U., which enforces democratic norms, has threatened Orbán with sanctions and legal action.

Read more: Why a Children’s Book Is Becoming a Symbol of Resistance in Hungary’s Fight Over LGBT Rights

In previous elections, Orbán’s political opposition was divided. This time things are different: In April, the six major opposition parties will set aside their rivalries and unite behind one candidate, Péter Márki-Zay, a small-town Catholic mayor who has won support across the political spectrum for his brand of anti-corruption conservatism.

If recent polls are anything to go by, the United Opposition poses the first credible challenge to the ruling Fidesz party since it assumed power in 2010. The battle for Hungary’s undecided voters and jaded Fidesz supporters has begun—while Orbán showers voters with tax rebates and social security payments, Márkari-Zay is galvanizing supporters around a “coalition of the clean”.

Philippines

Rodrigo Duterte may be barred from another term as president, but the current frontrunners in the May 9 election indicate that his brand of authoritarian populism is far from over in the Southeast Asian nation.

Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr.—the namesake and only son of the late Philippine kleptocrat and dictator ousted in 1986—has teamed up with Duerte’s daughter, Sara Duterte-Carpio, to form a ticket that consolidates two power political dynasties. Marcos is running for president; with Duterte-Carpio the vice-presidential candidate.

Despite leading in many polls, Marcos’ victory is far from assured. He faces at least four major challengers, including boxer-turned-senator Manny Pacquiao and current opposition leader Vice president Leni Robredo. He is also fighting several disqualification cases before the Philippine electoral commission involving a previous conviction for failure to file tax returns.

Critics fear that a victory for Marcos and Duterte-Carpio would only worsen the culture of impunity for extrajudicial killings and human rights abuses that characterized Duterte’s bloody war on drugs. He also cracked down on press freedom, and abandoned a U.S. alliance to flirt with China.

Australia

It’s been a turbulent period in Australian politics since the last election in 2019: an initially sluggish vaccine rollout, contentious climate policies, and diplomatic embarrassments have undermined the prospects of the center-right Liberal/National Coalition.

According to polling by The Guardian, Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s approval rating is at its lowest since he vacationed in Hawaii in December 2019 while the country was ravaged by devastating bushfires. The “Black Summer” of 2019-20 claimed 33 lives, over 3,000 homes and more than 20 million hectares (49 million acres) of land.

The fires have been directly linked to the effects of global warming, and Australia’s environmental record has come under increasing scrutiny. The country is the world’s leading exporter of coal, and while other countries move to sever ties with fossil fuels, Morrison pledged the opposite– famously bringing a lump of bituminous to a parliamentary debate. In November, he declared Australia would achieve net zero carbon emissions by 2050, but ruled out enshrining the target in law.

While Morrison’s Liberal Party is still the most trusted by voters to deliver national security and economic prosperity, Anthony Albanese’s Labor now ranks higher on international relations, climate change, and welfare. Polls show the race will be tight: according to The Australian, the majority of voters believe Labor will win, yet Morrison remains the preferred candidate for prime minister.

Colombia

Colombia’s 2018 presidential election saw the far-right candidate Ivan Duque defeat his far-left rival, former guerrilla member and Senator Gustavo Petro, to become president. Next year, the scales could tip the other way, as the country goes to the polls for congressional elections in March and to choose a president in June. Duque is now the country’s least popular president since polling began in 1994, at over 70% disapproval, while Petro looks stronger than ever.

The center still stands a chance, too. Moderate candidate Sergio Farjado barely missed the runoff in the 2018 presidential election, as Petro beat him for second place by a margin of 1.3% of total votes cast. According to analysts from risk consultancy Control Risks, reported by Bloomberg, the right will likely use the crisis in Venezuela as “a fear tactic against leftist policies—a strategy that has historically shaped the political feelings and opinion of many right-wing voters.” This could push undecided voters towards more centrist candidates.

Term limits mean Duque can’t run again in 2022. His party, the Democratic Center, will field a U.K.-educated former Finance Minister, Óscar Iván Zuluaga, who faces a tough fight convincing Colombians to vote for a continuation of leadership, given the wave of protests against increased taxes, corruption, and healthcare reform proposed by the government, which began in April 2021. A U.N. report found that police brutality was to blame for at least 28 deaths during the protests.

Kenya

Since the 1992 introduction of multiparty politics in Kenya, the country’s politics have been split along tribal divisions rather than political ideologies, and frequently tarnished by ethnic violence. That was the case in the 2017 ballot, which had to be rerun because of irregularities.

Afterward, president Uhuru Kenyatta, son of the country’s founding president, made peace with rival Raila Odinga. Kenyatta also proposed changes to Kenya’s constitution to promote power sharing among ethnic groups. But nothing is clear. In May the country’s High Court ruled that the amendments were illegal, and critics have accused Kenyatta of using the changes as a political maneuver against his ascendent deputy, William Ruto. The men have fallen out publicly, and Ruto is the frontrunner to succeed Kenyatta as party leader; term limits bar Kenyatta from running for a third term.

The general election is in August. At this point, Ruto is leading Odinga in the polls by 15 percentage points. But between the high cost of living, unemployment, hunger, the COVID-19 pandemic, and corruption, only 19% of Kenyans believe their country is headed in the right direction.

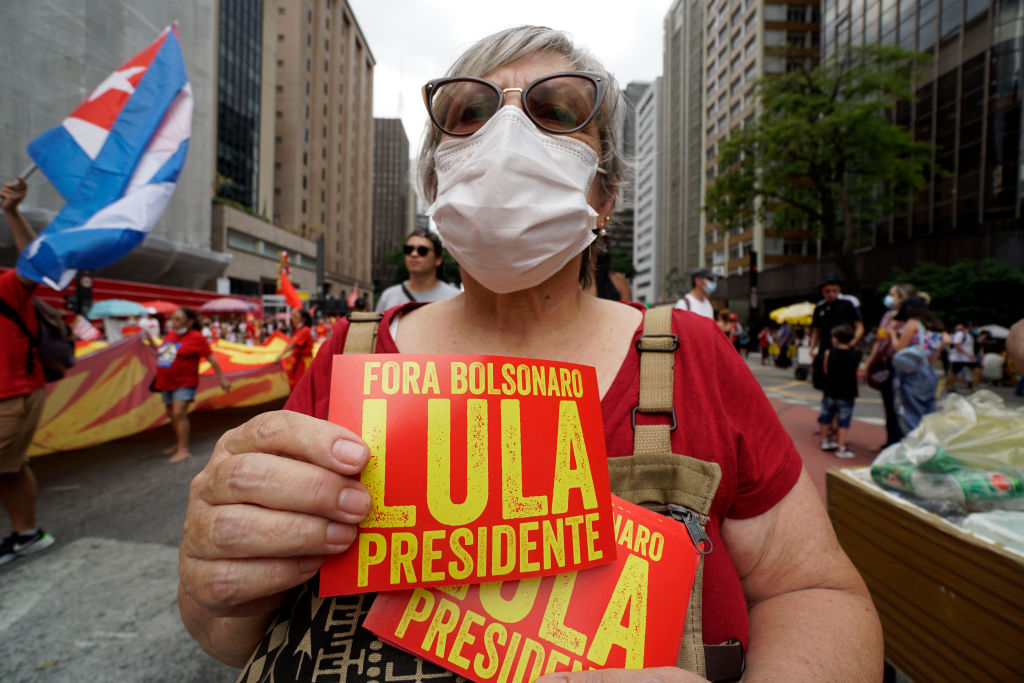

Brazil

Since being elected president in 2018, Jair Bolsonaro has built a reputation for denialism, first of the climate crisis, and then the pandemic. While dismissing COVID-19 as a “little flu,” the populist presided over the second highest official death toll in the world. In October 2021, Brazilian senators voted to recommend charging the president with crimes against humanity, citing pursuit of herd immunity policy and spreading COVID-19 disinformation.

Bolsanaro, a supporter of the military dictatorship that ruled Brazil from 1964 to 1985, has also undermined judicial independence, encroached on Indigenous land rights to clear the Amazon, and persecuted critics. Amid soaring inflation and a record drought, his approval ratings fell to a record low of 19% in late November,

“Only God” can remove him from power, Bolsanaro told tens of thousands of supporters in September. Nonetheless, the election is set for October 2022. Bolsonaro will likely face former leftist president Luis Inácio Lula da Silva whose 2017 corruption conviction was overturned in April.

Lula, set to be the candidate of the leftist Workers Party, is also a divisive figure. Yet recent polls suggest that if elections were held today, Lula would win 46% of the votes to Bolsonaro’s 23%. Having condemned Bolsonaro’s “genocidal” handling of the COVID-19 pandemic, Lula is promising voters relative moderation and stability.

U.S.

On Nov. 8 2022, two years after Joe Biden beat Donald Trump, U.S. voters return to the polls to elect members of the House of Representatives and a third of the Senate. Midterm elections are traditionally bad news for the President whose term they bisect: in the past seven decades the president’s party has lost on average twenty-five House seats in them.

Biden’s 42% approval rating, according to Gallup, is lower than that of any other recent president at this point in office except Donald Trump. The Democrat is burdened by the world’s highest number of recorded COVID-19 deaths, rising inflation, a tarnished diplomatic reputation, and a Build Back Better bill that has not passed despite his party controlling—for now—both the House and the Senate.

Democrats can point to a massive pandemic relief bill, and a bi-partisan infrastructure package that Trump only promised. But candidates planning to run on the expansion of benefits and climate investments in Build Back Better instead are pursuing a goal of damage limitation and bracing for midterm results that could put wind in the sails of Biden’s arch rival for 2024.

— With reporting by Chad de Guzman and Amy Gunia

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com