Andy Byford was feeling guilty.

It was March 2020, and he had just left his job as head of the New York City Transit Authority, after Governor Andrew Cuomo moved him off a massive revamp of the ailing subways. Stuck in his English hometown of Plymouth because of pandemic travel restrictions, he sat feeling “frustrated and impotent” as COVID-19 decimated ridership and revenues in public transit in New York and around the world. “Had I known the full horror of what was to emerge,” Byford, 55, says grimly, “I would have put my resignation on hold and stayed to see New York City transit through the crisis.” He even reached out to the chairman of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) and offered to come back, he says.

But Byford, one of the world’s most respected transport leaders, didn’t have to go back across the pond to find a transit system that needed his help. In June 2020, he took over as commissioner of Transport for London (TfL), the agency responsible for the city’s public transit. On a chilly mid-December afternoon, a 3 p.m. sunset already dulling the blue over the British capital’s skyline, Byford sits straight-backed in a glass-paneled meeting room at TfL’s headquarters and lays out the “sobering” state of the system. TfL’s sprawling network of underground or “tube” trains—the world’s oldest—lost 95% of its passengers in the first lockdown of spring 2020, and buses, boats and overground trains fared little better, hemorrhaging around £80 million ($110 million) a week during the strictest periods of lockdown. As the city lurched in and out of restrictions, tube ridership never climbed above 35% of 2019 levels.

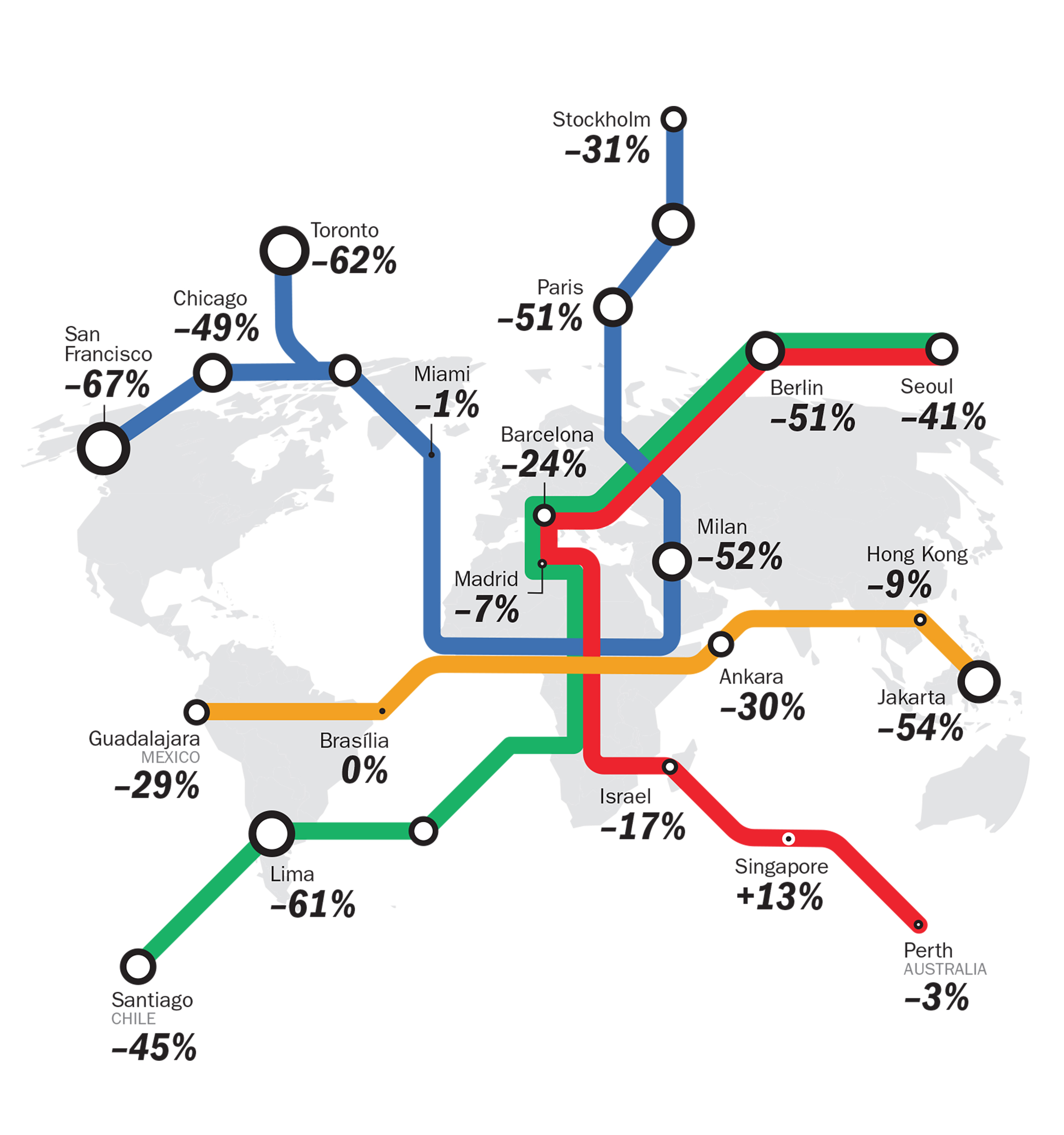

The pandemic has not only caused an immediate fall in ticket revenues for the world’s public transit networks—rail ridership in Barcelona, Moscow, Beijing and New York City at times plummeting 80%—in some cities it also has thrown into question the future of mass urban transportation. Like the sleek 11-story building where Byford was one of a handful of employees not working from home this winter, offices from San Francisco to Hong Kong sit mostly empty. Major companies contemplate a shift to remote work, and city residents consider moves out of the crowded, polluted urban centers that have made lockdowns more unpleasant. Fears of sharing confined spaces with strangers have fueled soaring demand for used cars in Mexico, India and Europe. A U.K. survey found attitudes toward public transit had been set back by two decades, with only 43% of drivers open to using their car less, even if public transport improves.

The implications reach beyond Byford’s industry. If people move from mass transit to cars, government targets on reducing emissions to fight climate change will move out of reach. Low-income communities and essential workers will be stuck with poorly funded or bankrupt systems as the wealthy move in cars or stay home. Economies will slow as it becomes more difficult for workers, consumers and businesses to reach one another. “Transportation policy is climate policy, economic policy and equity policy,” says Janette Sadik-Khan, who served as commissioner of the New York City Department of Transportation under Mayor Michael Bloomberg. “Restoring transit to full strength and investing in its future has to be viewed with the same urgency as restoring water or power lines after a national natural disaster.”

Byford is trying to persuade the U.K. to do just that. His relentless chipperness and nerdish fascination with intervals between train arrivals belie his success as a shrewd political negotiator. Resisting what he calls “the unsophisticated knee-jerk reaction” of service cuts, he has helped secure more than £3 billion in funding packages to keep TfL running. But he says ensuring cities have the transit systems they need in five years requires more than just stopgap crisis solutions. Byford is pushing for new innovations during the pandemic, an overhaul of TfL’s funding model and a longer-term multibillion-dollar government-support deal. “My message to our leaders is: Don’t see transit as part of the problem,” he says. “It’s part of the pathway out of the pandemic.” If he can set London on that path, he’ll give city leaders around the world a road map to follow.

As a teenager growing up in Plymouth, a coastal city home to the largest naval base in Western Europe, Byford had thought he might join the navy. In the end, after leaving university, he brought his efficiency and leadership skills straight to TfL, working as a tube-station foreman. It was something of a family business: his father had worked there, and his grandfather had driven a bus for 40 years, including through the Blitz when German bombs pounded London in World War II. But he was mostly drawn, he says earnestly, by “the buzz of operations, never knowing what the next day will bring” and “a passion for customer service.”

Byford sees himself as “naturally gregarious.” That quality—exercised in regular trips around TfL’s network to meet Londoners—has powered him through a career in the often thankless task of being the face of city transit systems. After leaving TfL and working on England’s railways in the 2000s, he took over the trains in Sydney. He speaks cornily about fostering “team spirit” and his love of going for a pint with colleagues on a Friday, prepandemic. But he doesn’t suffer fools. While overhauling Toronto’s failing transport commission from 2012 to 2017, he fired the manager of a line-extension project that had dragged on too long and replaced the team himself. At the MTA, he became known for his hands-on attitude, earning the nickname Train Daddy among fans and on social media. Though Byford cut his time in New York short, leaving his “Fast Forward” plan to remake subway signaling, bus routes and station access in his successor’s hands, transit experts hailed him for putting a previously hopeless system on the right path. “Andy’s attitude and his messaging were great, certainly refreshing for our political atmosphere; it was almost more than we deserve,” Sadik-Khan says. “He really restored New Yorkers’ confidence in transit. And that’s a tough hill to climb.”

Byford’s tenure in London is off to a less glamorous start. He contrasts his arrival at TfL last summer with his first day in New York City in 2018, when he was swarmed by a crowd of reporters at Manhattan’s Bowling Green station, excited to meet the Brit who had come to fix the subways. In pandemic London, there was no welcoming committee. “I just sort of wandered in and told reception who I was,” he says. A gigantic flag that he had commissioned for his MTA office, celebrating his hometown soccer team Plymouth Argyle, now hangs slightly cramped in a small side room at TfL.

But the scale of his task in London, overseeing 9,000 buses and 250 miles of underground tracks as well as overground rail, cycling, taxis, boats, roads, bridges and tunnels across London’s 600 sq. mi., dwarfs his previous jobs. He must also grapple with TfL’s unique vulnerability to falls in ridership, which on the underground last year reached its lowest level since the 19th century. The network relies on ticket revenue for 72% of its operating income, far higher than the 30%-to-50% norm in major Western transit systems. The rest of TfL’s cash flow comes mostly from road-compliance charges, such as a congestion charge on cars, commercial activities like renting out properties, city taxes and local government grants. Prepandemic, TfL hadn’t received U.K. government funding for operations since 2018, Byford points out proudly.

Some cities have responded to the loss of passengers with service cuts, including Paris, where authorities cut metro and train service by 10% on most lines this March. In New York, the MTA cut service on two lines by 20% last spring, but the agency has avoided the swinging 40% to 50% service cuts it warned of in late 2020, thanks to federal relief funds. In London, TfL has maintained near normal service throughout the pandemic. Byford says he’s determined to resist “the siren voices that say we should mothball lines, defer maintenance, get rid of capacity in order to achieve a short-term financial objective. Cutting service leads to just a downward spiral.”

That downward spiral is well documented in cities like Washington, D.C., where deferred maintenance and underinvestment in the 2000s have led to long safety shutdowns. When service becomes more irregular, people who can afford the expense will increasingly drive, take cabs or stop traveling in the city altogether. Ridership continues to fall, so revenue falls, and service and maintenance are cut further. “You end up creating a kind of transit underclass of people who have no other option and are still dependent on a lower-quality offering,” says Yingling Fan, a professor of urban and regional planning at the University of Minnesota. “Mass transit only works if it has the mass.”

Keeping the “mass” right now requires support. Byford and Mayor Sadiq Khan negotiated bailouts of £1.6 billion in May and £1.8 billion in October. The deals had to overcome strained relationships between the mayor, who is part of the opposition Labour Party, and the right-wing Conservative government, which has pledged to prioritize other regions in the pandemic recovery. In exchange, Khan agreed to raise city taxes and make £160 million worth of cuts to TfL, mostly in the back office. Two long-term rail-expansion projects have been mothballed.

But Byford prevented two threatened cuts that he says epitomized the short-term thinking that kills public transit: first, planned signaling updates for the busy Piccadilly line that runs all the way from Heathrow Airport to Piccadilly Circus and beyond; second, the Elizabeth line. The largest rail project in Europe, it will connect eastern and western towns with Central London, adding a full 10% to the network’s capacity. Delayed from its original 2018 completion date, and with some £18 billion already spent, the line narrowly avoided being shelved in November after the U.K. government refused to provide a final £1.1 billion TfL asked for to complete the project. The city agreed to take £825 million as a loan and find a way to deliver the line with that. Byford promises “no more slippage” on the new opening date of 2022.

Byford is now negotiating with the government on his demand for £3 billion to cover operating costs in 2021 and 2022, and a further £1.6 billion a year until 2030 to allow TfL to reduce its dependence on fares by growing other revenue streams, like its housing division, and make long-term improvements. He argues that TfL is an essential motor of the green recovery that Prime Minister Boris Johnson has promised. For example, Byford wants to “expedite” the electrification of London’s massive bus fleet, which might compel manufacturers to set up a production line.

Most urgently, the money is needed to keep the city that provides 23% of U.K. GDP moving. In New York, a study by the NYU Rudin Center found that steep MTA cuts would trigger an annual GDP loss of up to $65 billion. “You can’t just turn public transport on at the drop of a hat,” Byford says, citing the need for continued maintenance and ongoing scaling up of capacity. “You’ve got to keep planning, you’ve got to keep asking: What will the city’s needs be in the future?”

The pandemic has made that question much harder to answer. London’s population is set to decline in 2021 for the first time in three decades, losing up to 300,000 of its 9 million people, according to a January report by accountancy firm PwC. It’s too soon to say if that’s the start of a long-term postpandemic trend. But even if the population remains stable, a mass shift to home work, predicted by some, would have “enormous implications for the future of public transit use,” says Brian Taylor, director of the Institute of Transportation Studies at UCLA, “because transit’s ability to move a lot of people in the same direction at the same time is its [big advantage over] cars.”

And a long-term shift from transit to car use in densely packed cities would cause major headaches for city leaders. In New York City, where the number of newly registered vehicles from August to October was 37% higher than in the same period in 2019 across four of the five boroughs, residents compare the fight for parking spaces to The Hunger Games.

Byford rejects the idea “that mass travel to offices is a thing of the past, or that Central London is going to become some sort of tourist attraction preserved in aspic.” In a “realistic” scenario, he expects TfL ridership to recover to 80% of 2019 levels in the medium term. That still adds up to around £1 billion a year in lost revenue, he says, meaning TfL will have to restructure to make savings and potentially redesign bus routes and some service frequency based on how people are using the city. “But there’s still a lot of things we can do, in public policy and in TfL, to convince people not to get back in their cars,” he says. “My job is to make public transport the irresistible option.”

The crisis facing public transit over the next few years poses a grim threat to cities, at least in the short term. But city leaders also see hope for the long term in the global reckoning with the status quo that the disruption of COVID-19 has triggered. Many are considering how to use the lessons of this time to positively reshape cities for the postpandemic era. And the loser is cars. From Berlin to Oakland, Calif., roads have been blocked to create miles of new cycle paths, sidewalks have been widened and new plazas created. The “renaissance of innovation” that has occurred over the past year will accelerate cities’ transition to a more sustainable, low-emissions way of life, says Sadik-Khan, whose tenure in New York City was marked by the creation of hundreds of miles of bike lanes.

In London, as well as widened sidewalks and the creation of new low-traffic neighborhoods, Byford and Khan are making it increasingly expensive to drive in London. Since its introduction in 2003, the city’s congestion charge, a daily levy on cars driving in the city center, has helped cut congestion there by a quarter in three years, and, with support from both right- and left-wing local governments, it has become a model for cities wary of the political risk of upsetting drivers. In June, the city increased the daily charge to $21, from $16, and expanded its hours of operation, for now on a temporary basis. In October, the “ultra-low emissions zone,” which since 2019 has charged more polluting vehicles $17 a day in Central London, will expand to cover a much larger area. And Mayor Khan is considering a new toll for drivers who come in from outside the city. For Byford, who has never owned a car, it’s promising. “The mayor’s goal has always been to increase the percentage of people using public transit, walking or cycling to 80% by 2041,” he says. “Before, that was seen as ambitious. I think we can definitely do that now.”

The postpandemic moment could potentially be a turning point. “Many are arguing this pause could give us an opportunity to reallocate street space, to reconsider how much curb space we devote to the storage of people’s private property, which cars are,” says Taylor. If cities manage to improve public transit and phase out car use on their streets, in a few years they won’t just have less pollution and lower greenhouse-gas emissions. Streets will be safer and more pleasant to walk through, increasing footfall for retail and hospitality sectors. Businesses will have more flexibility to set up stalls or outdoor seating. Curbs can be redesigned to be more accessible for the disabled. It all depends on the decisions city leaders take now to “intelligently manage automobiles” and protect public transit, Taylor says.

It may be hard to knock the car off its pedestal in the U.S. Many of its cities were designed around the automobile, and analysts say U.S. policymakers tend to treat public transit as part of the welfare system, rather than as an essential utility as it is considered in Europe and Asia. After the 2008 recession, U.S. transit agencies were forced to make cuts so deep that some had not recovered before the pandemic.

But transit leaders see some signs of the political support transit needs to survive and thrive. On Feb. 8, the U.S. Congress approved an additional $30 billion for public transit agencies, softening the blow from the $39 billion shortfall predicted by the American Public Transportation Association. And Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg, who spearheaded controversial initiatives to reduce car use as mayor of South Bend, Ind., told his Senate confirmation hearing that the current moment offers a “generational opportunity to transform and improve America’s infrastructure.”

Global transport is undergoing a transformation, despite the pressures of the pandemic. The market for low-emissions electric buses is thriving, with cities from Bogotá to Delhi ordering hundreds of units over the past year. Transit agencies, including TfL, are partnering with delivery companies to make the “last mile” of trips more efficient. Meanwhile, urban-planning concepts like the “15-Minute City,” championed by Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo, are scaling back the need for long commutes and unnecessary journeys.

Fast Forward, Byford’s attempt to transform New York City’s transit, is “somewhat on hold at the moment,” he says. But he urges his former colleagues not to allow the pandemic to wipe out their ambition. “That plan will ultimately serve New York well, and it should not be left on the shelf,” he says. Byford is unlikely to return anytime soon, though. He says he doesn’t miss the complexity of being answerable to both city and state governments, and he loves working with a “very enlightened” mayor in Khan. Pointedly omitting leadership in New York, he adds that he also had “excellent relationships” with two successive mayors in Toronto, the premier of Ontario and the minister of transport in New South Wales.

Hard as it may be for some New Yorkers to believe, what Byford does miss about his old job these days, as he roams TfL’s quiet trains to monitor the network, is riding the subway. “It’s like a different world underground,” he says, recalling the entertainers and “the kaleidoscope of experiences” he would witness. “In London, people don’t tend to look at each other on the tube, let alone speak. I’m back into being my more reserved British self.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Ciara Nugent/London at ciara.nugent@time.com