In Minneapolis, the first days after George Floyd’s killing exist in memory as kind of a blur. Even so, the burning of the Third Precinct police station on May 28 was a signal event, and not only for residents of the south side, where Floyd was killed and so many buildings went up in flames. Five miles to the north, residents of the city’s other substantially Black area worried the chaos was coming their way. That night, Phillipe Cunningham, a city-council member representing part of North Minneapolis, drove around for 2½ hours without seeing any cops at all. They were hunkered in their stations.

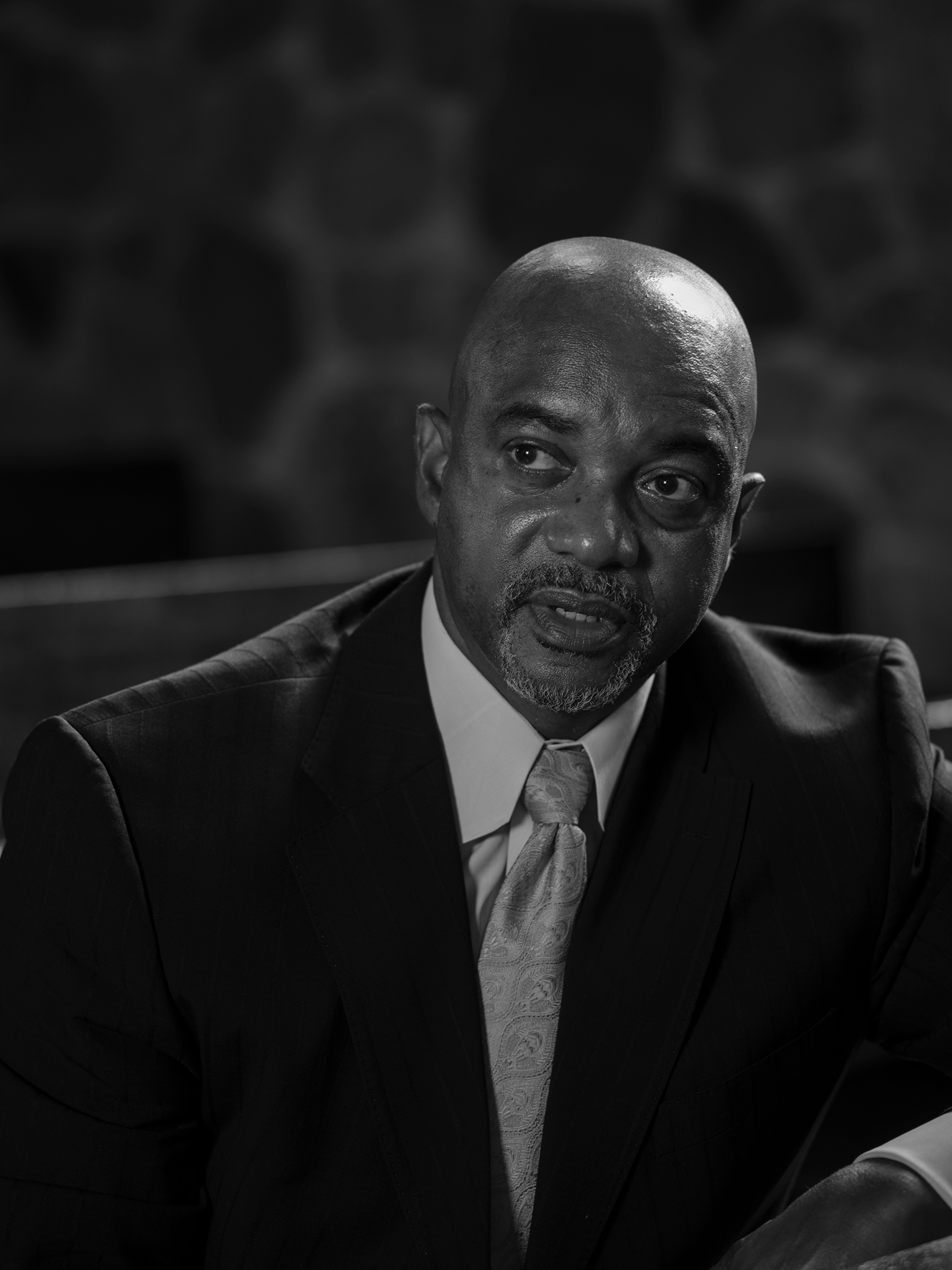

In the void they’d left, a community stepped up. On Emerson Avenue, gang members took pride of place in the phalanx guarding the So Low Grocery Outlet, one of the north side’s only two super-markets. “We locked it down for seven nights,” says the Rev. Jerry McAfee, a Baptist preacher who works with gangs. Members of his patrol were identifiable by green and white bandannas and weapons not necessarily displayed. “Here’s what I can tell you,” McAfee says. “Fort Knox wasn’t guarded any better.”

In an integrated neighborhood a mile and a half away, unarmed residents in orange tees formed a perimeter around the other supermarket. Night after night, they challenged the white youths circling the block in pickup trucks without license plates, vetted unknown volunteers and—it dawned on more than one of them—edged toward an approach to public safety that might supplant the deeply flawed one that had provoked the mayhem around them.

What could replace the police? The question, until recently confined to activist circles, has been forced into national debate by a brutal logic: If the killing of Floyd truly left Americans with a resolve to address systemic racism in their country, shouldn’t the starting point be the system that produced his excruciating death? Almost two weeks after now former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin knelt on Floyd’s neck, the Minneapolis city council concluded that its police department was beyond reform and must instead be replaced. In a unanimous vote, the council embarked on a yearlong quest to produce a “new model for cultivating safety in our city,” explicitly steered by the desires of the people most oppressed by the current one.

If Minneapolis produces a new safety paradigm, the implications will be profound—reaching beyond the horror of police killings toward a rethinking of a criminal-justice system lamented by liberals and conservatives alike. If it fails, a status quo deeply rooted in the control of Black bodies will remain the norm, “and this will have been a nice little moment in history where we almost did something,” says Jeremiah Ellison, a council member for Minneapolis’ north side.

Residents’ safety hangs in the balance, and so does a movement so new, it still needs a good name. Though Minneapolis council members linked themselves to “defund police” by announcing their bold initiative while standing behind letters spelling out the protest slogan, their ambition can’t be summed up in two words, much less two words with the potential to be so easily misunderstood. To succeed, the movement needs a more precise slogan than “defund,” to capture an actual intention that has been all but impossible to articulate because it comes, for now, from another world, one that acknowledges that Black lives matter.

“We’re in a time of theorizing,” says Oluchi Omeoga, a co-founder of the Minneapolis activist group Black Visions Collective. “We’re trying to build a world that does not exist yet.”

In that world, the core mission of public safety is not enforcement but care, and a call to 911 is more likely to produce a specialist in the problem at hand than a police officer carrying a gun, 15 lb. of gear and the additional weight of three centuries of racialized law enforcement. The new system would look for solutions from the very communities that the old system regarded as the sources of problems and guide investment accordingly. Law enforcement would not disappear, not in a country with more guns than people. But the officers who remained would be highly professional and trained in an ethos of valuing life. They would be focused on solving people’s problems rather than locking people up and would work alongside those they serve.

Countless hours have been spent in the past few weeks discussing what has gone wrong in policing, but Minneapolis voters may take action as early as November, in the form of a referendum that would allow city lawmakers to continue exploring a new approach to safety. Everyone already knows it’s going to be hard. Camden, N.J., a city more than a thousand miles away, has been held up by many as an illustration of what the existing model can be. But the experiences of citizens there reveal not just the potential for real change but also the limits of what has been possible—at least so far—while still keeping residents safe.

“As an elected official, I will not make any decisions whatsoever that will decrease safety,” says Cunningham. “Everything that I do is about increasing the safety of the residents. And it is very clear that this system that we have now is not doing that.”

One thing the system does have is longevity. Today’s modes of policing in the U.S. can be traced back hundreds of years, and with them an understanding of why, in 2020, according to the database Mapping Police Violence, a Black person is three times as likely as a white person to be killed by police.

In America’s early years, towns protected themselves informally, with the help of a part-time night watch—though night watchmen were notorious for simply using their shifts to get drunk. The country’s first publicly funded police department started in Boston in 1838, with the primary goal of protecting property.

But in some places, “property” included human beings. “In this country, for the years that cover the 1600s to the mid–19th century, the most dominant presence of law enforcement was what we call today slave patrols. That’s what made up policing,” Harvard history professor Khalil Gibran Muhammad told NPR this year. These patrols were tasked with providing swift punishment for runaways and enslaved people who broke the rules, and assuaging the white population’s fear of a revolt.

Long after the Civil War, sheriff’s departments administered slavery’s post-bellum by-products, segregation and Jim Crow oppression. During World War II, after thousands of African Americans moved to Oakland, Calif., to find work in the shipyards, the city responded by recruiting Southern police officers. In the postwar boom, redlining—which prevented home loans from going to Black people—enforced segregation of neighborhoods and denied Black people homeownership, the primary route to middle-class wealth. Maintaining that system reinforced the imperative of the slave patrol: vigilant oversight of a population perceived as threatening despite, or perhaps because of, its being oppressed.

The modern civil rights movement in the 1960s changed laws but not the fundamental nature of policing. Black and brown people have been disproportionately targeted by programs like the New York police department’s street-stop effort known as stop and frisk, which a federal judge ruled in 2013 was used in an unconstitutional way. The past few months have served as a searing reminder of how those dynamics play out in today’s society. As protesters took to the streets, speaking out against racism and law-enforcement violence, some departments seemed to prove their point; in New York City in May, police drove an SUV into a group of demonstrators. In Philadelphia, police teargassed protesters trapped in a channeled roadway.

The recent “militarization” of local police—with departments nationwide receiving armored vehicles left over from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan—obscures more than the faces of officers: the truth is, cops rarely confront violent crime. Cadets spend most of their average 21 weeks of training on defensive tactics and firearms. But time-use studies find that patrol officers mostly deal with traffic, medical calls, accidentally tripped burglar alarms, arguments and the like. In 1999, when Baltimore was called the most violent city in America, its mayor said its police spent 11% of their time on crime, half of that not serious. In smaller places, studies have found that all crime occupied 7% to less than 1% of an officer’s time.

“There’s a mismatch between how we’ve constructed cops and what they actually do,” concludes New York University law professor Barry Friedman in a 70-page paper he wrote in March, titled “Disaggregating the Police Function.”

Officers are not only unequipped to handle what former Milwaukee police chief Ed Flynn has called the “intractable social problems that are dumped in the laps of our 25-to-30-year-old first responders.” They also often arrive heavy with the tools of forceful control: baton, Taser, firearm. Thanks to redlining and its reverberations, the neighborhoods where those social problems tend to run especially deep are often those where Black and brown people have been confined. And as Phillip Atiba Goff, a co-founder and the CEO of the Center for Policing Equity, a think tank focused on addressing racial gaps in law-enforcement impacts, points out, they are also the areas that tend to be highly policed: Black and Hispanic people are more likely than white people to have multiple interactions with the police.

It’s a dangerous mix and has left many minority communities with scant reason to view the police as allies. Especially in the years since smartphones made it easy to share high-quality video, the world has been treated to a view of a problem that is much older than that technology, whether it’s an officer caught on camera shooting someone in the back or using a choke hold: such incidents define policing for Black Americans. And beneath the headline-making moments caught on video lie policies from the Fugitive Slave Act to stop and frisk.

That history is a large part of why many activists and academics alike have come to believe that the relationship between Black Americans and U.S. police can’t be solved with incremental change. “The community brings its problems to the police to work out solutions within the community, but the police don’t have any of the tools that we really need to solve these problems,” says Alex Vitale, a professor at Brooklyn College and the author of The End of Policing, which argues that reform, training and department diversity don’t go far enough. (A study released in July found that diversity on a force did not in fact lead to less police violence.)

But changes on a nationwide scale will be challenging. There are around 18,000 police departments in the U.S. There is no real federal oversight when it comes to policing agencies. Police departments across the country look mostly the same because, by and large, it has been assumed that there is pretty much one way of doing things.

“If we go down this path to re-examine what policing looks like, we need to make sure we know what really works. We need to look at what our potential outcomes will be,” says Joseph Schafer, a professor of criminology and criminal justice at St. Louis University. “If you were going to sit down and create a policing system from scratch, it wouldn’t look like what we have right now.”

The citizen patrols left the streets of North Minneapolis when the police returned. But for several days after, McAfee was still hearing from gang members, looking not for trouble but its opposite. “Most of the guys that we work with, they love this community,” he says. “They was still calling, showing up, ’cause they needed purpose.”

On the city council, Cunningham and Ellison were not the only members who saw opportunity in the unrest. The Minneapolis police department (MPD) was deeply troubled, and activists had been beating the drum for change. In 2017, on the 150th birthday of the force, a group called MPD150 published a history of the department’s brutal treatment, including the 1990 killing of 17-year-old Tycel Nelson, shot in the back as he fled, and the 2015 death of an unarmed Jamar Clark, which prompted weeks of protests. One chapter called for abolishing the department in favor of “community-led safety programs.”

That once radical notion had already been gaining traction among academics. Two years after serving on President Obama’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing, Yale Law School professor Tracey L. Meares wrote that “policing as we know it must be abolished before it can be transformed.” Researchers at other major universities gathered at the same conclusion.

“It’s all broken in policing,” says NYU’s Friedman. “We have decided to treat the police as a one-size-fits-all remedy for everything that’s wrong.” Friedman argues that most of the duties that have accreted to police would be better dealt with by someone else, including traffic enforcement (which parts of New Orleans have awarded contract rights to a civilian firm to handle), care of the homeless (fielded in Denver by volunteers), drugs (more widely understood since the opioid crisis as an addiction grounded in despair) and mental-health crises (which Eugene, Ore., has dealt with since 1989 using counselors from a nonprofit that fields some 20% of 911 calls).

Mental illness accounts for a growing share of the jail population nationwide. That, in turn, argues for a public-health approach to safety, says Ebony Morgan, whose father was killed during an encounter with police in Eugene in 1996. A registered nurse, she works with the CAHOOTS program (short for Crisis Assistance Helping Out on the Streets), which last year sent a crisis counselor and a medic to 24,000 calls. “If you have the option that doesn’t have the potential to escalate into something fatal, that is just so important,” she says. “It’s about trying to shift that lens back to the community responsibility, for folks to acknowledge that the way that we as a society treat people will have an impact on the rest of their life, and maybe even its duration.”

In her classes at Johns Hopkins University, political scientist Vesla Weaver presents two charts comparing the world’s most developed countries. The first shows spending on social welfare. “The U.S. is way out there in the stingiest part of that graph,” she says. “Then on the other side, I show public-safety expenditure. We are way out on the extreme other end.” Her point is a stark one: reorienting police funding “almost involves a recharacterization of the American state.”

That may well be the idea embedded in the assertion that Black lives matter. And like the movement that carries the name, the new safety paradigm percolated from the grassroots. Weaver says the closest things to a pilot program were efforts, undertaken over the past five years in poor neighborhoods in Chicago and Baltimore, that relied on a community’s own self-knowledge. “This is what safety really feels like,” she says. “It doesn’t mean the police. Us harvesting our own things. Us being mentors to young men in our neighborhoods.”

This, then, was the positive alternative taking shape when Floyd’s death abruptly pushed open the door to new ideas. But dipping a toe in the waters of change has proved ill suited to the outraged anger that has swept across the country since late May. Calls to “defund the police” rose to the top—for some, shorthand for the argument that public funding spent on law enforcement would be better spent on social services, but for others an idea that raises the specter of complete lawlessness. In a few places, the battle cry has been taken literally: the Los Angeles police department’s budget was cut by $150 million, the NYPD’s by $1 billion. The amounts may be invested instead in social programs, perhaps even for more than a fiscal cycle.

But only the City of Lakes appears intent on what its city council terms a “transformative new model for cultivating safety.” The Minneapolis council’s June 12 resolution called for a full year of study, “centering … stakeholders who have been historically marginalized or under-served by our present system.” After moving very quickly—“It all just happened so fast, to be honest,” says Cunningham—the idea is to proceed deliberately and consult widely.

“The only way we can solve this problem is, you gotta talk to me,” says Olivia Pinex , who was working at a south Minneapolis food bank on one recent day. “There’s a lot of solutions inside the community, but the problem is the police officers want to kill us first and then talk to our family. How about we talk first?”

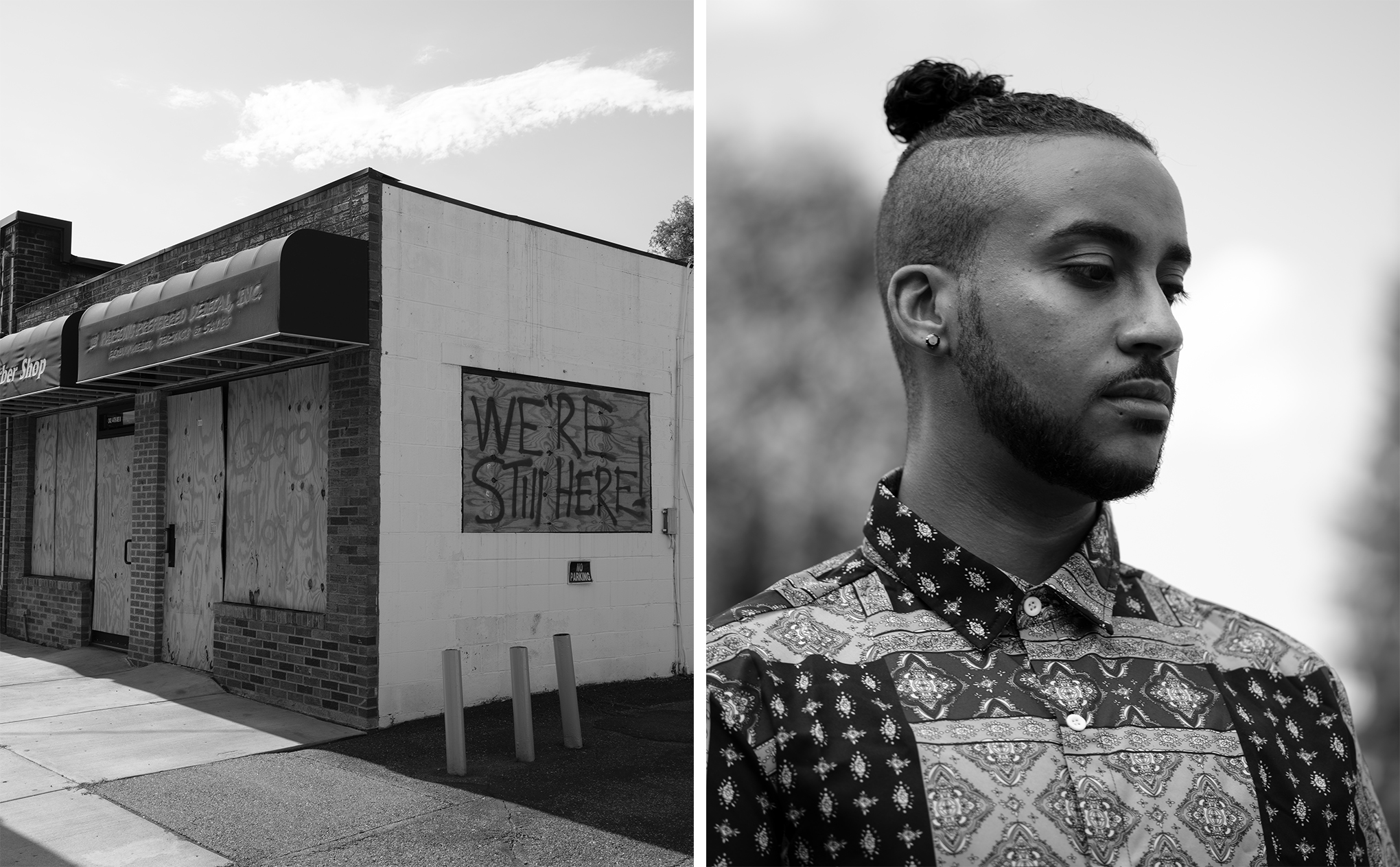

No matter how that conversation goes, nothing substantial can happen without a change in the city charter. Getting a referendum to that effect in front of voters is a complicated process, opposed by Mayor Jacob Frey, who would lose line authority over the police department—and by the powerful police union. Also working against the council is a wave of violence: “gunfire incidents” in Minneapolis were up 224% in June and 166% in July, compared with a year earlier. At the moment, voters may feel they face a choice as stark as the contrasts on display along the corridor of Lake Street, where the plywood on storefronts alternates between elaborately rendered messages of aspiration (Unlearning Whiteness) and desperate pleas (Don’t Burn and Kids Live Here). With nothing in between.

“The people who stoked this fire of ‘defund,’ they need another way to say it,” says Houston White, who owns a luxe barber-shop on the north side. “It’s a PR and narrative nightmare. This is such a fragile discussion.” White, for instance, says he would prefer that a call about a loud stereo not be answered by “an officer with his hand on a gun.” But he also remembers his troubled youth and says the threat of arrest helped scare him straight.

In truth, not even activists who call for “abolition” expect the police to vanish. “I don’t think that the Minneapolis police department will be gone even next year, even in five years,” Black Visions Collective’s Omeoga says. “But it’s a transition. We know that this system is not working for us.” If a referendum to change the city charter does pass (or if the process takes so long that the question doesn’t get in front of voters until November 2021), the council will have more time to try to bring around skeptics, some of whom are indignant at not being consulted already. One is McAfee. The preacher casts the Black Lives Matter generation—intersectional and independent and often younger—as at once naive and rigid.

And yet McAfee seems to be on the same page as many Black Lives Matter activists. He arrived at his interview with TIME in sweats, having rushed to a home where a gang member was on the edge of violence. He had organized volunteers to stand between protesters and the north side’s own police precinct, and Minneapolis police confirm asking him to provide security at George Floyd’s memorial service. Years ago, McAfee says, “we had an on-call thing” that brought a “community-response team” to hospitals to head off retaliation after someone in the neighborhood was injured by another. That program was successful, he says, because the people have learned what works—they had to, given the risk of summoning police.

“What we’ve done for years is what the hell they’re talking about doing,” McAfee concludes.

It’s not so easy to formalize such arrangements into a municipal system. A buy-in from the current police chief would help (though it is highly unlikely, given his obligations to the mayor). As a Black veteran of the Minneapolis department widely admired for his efforts to change its culture, Medaria Arradondo is cited by activists as proof that the problem is the system, not individuals. But there will still be a place for cops in a new paradigm, and Cunningham recalls telling Arradondo, “I want you to know that while I don’t necessarily believe in reform, I believe in you. So if you could build your ideal force, if you did not inherit this system, what would that look like?”

Some have been looking east—to Camden, N.J., widely regarded as the current exemplar of change in urban policing.

There, Pyne Poynt Park, home of the North Camden Little League, presents a clear view of the Philadelphia skyline. On a mid-July day, as temperatures inched above 90°F, Bryan Morton, a community activist who runs the league, offered a group of his older players reminders from the sidelines as they warmed up and got ready for practice: “Don’t forget the pitching machine. Y’all know the layout.” Morton started the league in 2011 in response to the high crime rates in Camden, as a way to give kids something to do. At the time, he says, none of the parks in the neighborhood were safe for kids to play in.

The ball field’s waterside position is a little removed from Camden’s downtown, but the problems within the city had their way of reaching the park. Sometimes when it was time for practices to start, drug dealers would still be using the same space to sell. “Shoot-outs were common; high-caliber weaponry was the norm,” he says.

At around the time when the league was launched, Camden, which is majority-nonwhite and nearly half Black, was one of the poorest cities in the state, with a 2012 median household income of about $22,000 and a poverty rate of about 40%. It also had among the highest crime rates in the country. Even so, says Morton, the members of the city’s understaffed police force spent their time in their cars or planted behind their desks.

“When you think of shootings, you think they happen in the evening or at night,” says Wasim Muhammad, a lifelong resident of Camden and minister of its Muhammad’s Temple of Islam No. 20. “We started having gunfire in broad daylight downtown. It was just out of hand.” And, he says, the police weren’t helping. In his view, the department was like a structure too unsteady to be worth shoring up: “Sometimes a building can be so damaged it’s not that we’ve got to repair the building; we’ve got to tear the building down and start a new one.”

Which is, essentially, what the city did. At the time, its budget was already running at a deficit, and statewide financial issues led then New Jersey Governor Chris Christie to cut state aid that paid the salaries of hundreds of Camden city workers. Nearly half of the police department was laid off in 2011, and because the union was unwilling to negotiate pricey elements of their contract, no new officers were hired. When 2012 saw an all-time-high murder rate, the county and local government had the leverage to disband the department entirely; even the union couldn’t stop the move, not that it didn’t try. The department relaunched in 2013, under county control rather than the city’s. Many of the laid-off officers were rehired for the revamped department. Also new: when the department reunionized, it was under new leadership—leadership that Camden County communications director Dan Keashen says is committed to working with the local government to keep costs reasonable.

County freeholder director Louis Cappelli Jr. and former Camden mayor Dana Redd say they had two main objectives when they relaunched the department: reduce the crime rate, and make citizens feel safer. For Redd, a Camden native, this meant making sure residents had a voice in what the department would look like. “That’s probably the side that I’m very proud of, because while we were going through the difficult times in Camden, I spent quite an enormous amount of time meeting with the community, communicating with people,” Redd says. “I wanted to assure them that we weren’t going to quit because the going got tough.”

One thing the new department didn’t immediately solve was use of force and discrimination. As part of a major investigation of policing in New Jersey, in 2018, NJ Advance Media combed through data from every local department in the state; Camden’s use of force from 2012 to 2016 was on the high end. The investigation found a spike in complaints after the county took control and as crime began to drop; the vast majority were dismissed by the department. And even adjusted to account for population, a Black person in Camden was 8% more likely to have a police officer use force on him or her than a white person was.

Those numbers only started to change later. In 2014, the department instituted an “Ethical Protector” training program, after which excessive-force complaints began to fall, and about a year ago the department stepped it up with a new use-of-force policy—vetted by the Fraternal Order of Police and ACLU alike—that authorized deadly force only “as a last resort” and that was touted as a potential model for better policing nationwide.

Today, in Camden, officers have a mandate to de-escalate as often as possible. The department uses a virtual simulator to train officers to handle a wide variety of situations, from a homeless man who refuses to budge from in front of someone’s garage to a distressed man ready to throw his child off a bridge. In that training, whatever the scenario, the officer’s goal is to preserve life. The simulator isn’t the only technology in which the county has invested. The department can monitor blocks that are overdue for a visit and keeps tabs on whether officers are lingering in their cars or walking the streets. It reviews body-camera footage from the streets, studies it and tries to correct any mistakes officers might have made.

Joseph Wysocki, who was part of the old department, has served as the new department’s chief since 2019. His goal is to get his officers to build relationships with the citizens whose safety is their job. “You have to work with the community. It’s not us vs. them, it’s us together,” he says. Wysocki proudly recounts a department barbecue at which a local kid at first had to be cajoled into asking an officer for a plate, only to later be spotted playing basket-ball in the street with that same officer.

Some evidence in favor of the relaunch is not just anecdotal. Murders are down 63%, and robberies are down 60%. Overall violent crime is down 42%. It’s hard to pinpoint cause and effect here: these shifts took place in the context of a national period of economic growth, which reached Camden too, to an extent, as the poverty rate sank by over 5% by 2019. The unemployment rate, 10% in early 2012, came down to 4.4% by the beginning of this year; though the exact link between economic conditions and crime has proved hard to pin down, a certain amount of improvement in safety may be mere correlation. But some community members, like Morton, say the new police force has helped the city get there. And the park where his Little Leaguers play is no longer a drug-trade hot spot.

“Before the change, the police department did not care about our safety,” Morton says. “When they made the transition, they built partnerships with members of the community.”

That Camden is home to a community is plain to see. Its residential areas look worn down, but people who walk the streets wave to one another. Morton knows, however, that this community was skeptical about whether the relaunch would bring the needed change. To him, just as the police had to be held accountable, the people had to be open-minded about the possibility of moving beyond the past.

To others, seven years under new management has not resolved that skepticism. For one thing, the department still does not ethnically reflect the city it is protecting. “There is one Black captain,” says the Rev. Levi Combs III of Camden’s First Refuge Progressive Baptist Church. Metro police officers are disproportionately white, and most don’t live in the city. Combs dismisses the department’s rebirth as primarily a financial decision—city officials estimate they could be saving up to $16 million a year with the department under county control, in part by escaping perks that were baked into the old contract, though the savings in early years were not in fact as high as predicted—and the supposed community buy-in as mere window dressing. “It’s marketing the city of Camden to attract more white people and more affluent people,” he says. “We have a lack of jobs, homeownership, lack of education resources.”

Advocates of a new safety paradigm see Camden as a case study in the boundaries of reform. Freed of a recalcitrant union and trained to prioritize life, police may well be seen as less of a threat by the community they are meant to serve, they say. But that’s a long way from a transformational model of safety built not around policing but instead around investment in the lives of Black citizens, who for decades were viewed as a source not of solutions but of threats. “There is no investment in our community,” says Combs.

Sure enough, even as Camden’s experience has become the go-to example of revamped policing, the defunding movement has hit there too; after all, when the department was reimagined, the size of the force increased. While Wysocki acknowledges that Camden’s original police department was essentially “defunded” when it was shut down, he worries that a national movement to shift dollars away from law enforcement may hit departments in their budgets for officer training, the very aspect he believes has contributed to his city’s turnaround.

Camden shows that it’s possible to hit restart on a police department and to have public safety improve after such a move. But the city also shows that such a drastic change doesn’t guarantee a fix—and, perhaps, that there’s little reason for a department to wait to be defunded before it starts prioritizing the people it’s meant to protect.

This critical moment for the future of public safety is not America’s first. “We have been in crisis around policing before, and very little changes,” says NYU’s Friedman. “And I’m going to be extremely disappointed if we find ourselves in disappointment several years down the road.”

Thousands of people have taken to the streets across the nation protesting police brutality and systemic racism. At the same time, violent crime has surged in some cities. The usual summertime bump in crime may well be compounded this year by a pandemic that has left millions of Americans out of work-—Camden’s unemployment rate is even higher than it was in 2012—and, some officials have suggested, by slowdowns from some police forces unhappy at being publicly vilified. (Police departments tend to say they’re not slowing down, just overwhelmed.) But the residents of poorer neighborhoods are the ones who stand both to lose and to gain the most. And the recent violence is both ammunition for those wary of too much change too quickly and a reminder of the need for a public-safety solution that actually works.

“Some people look at [the new paradigm] as the removal of trained officials to deal with violent incidents,” says Goff of the Center for Policing Equity. “Police can help communities stay safe from the violence of crime. They can’t protect the community from the violence of poverty. Being poor is violent.”

If this summer proves to be a time for progress on the problems that make everyone feel less secure, the protests and the pandemic won’t be the only things that set 2020 apart. For some activists, it finally seems possible to take that difficult step forward on the unspoken but perhaps more crucial counterpart to “defunding” the police: funding communities to help them protect themselves. If one side of the coin is on display in Camden, the second side is not yet minted.

“I think that some of these words are easy to misinterpret,” Goff says of the effectiveness of defunding as a catchall term for what needs to happen. “I’m interested in having a brand-new conversation on what public safety looks like. I care more about making sure that vulnerable communities have the resources they need so they don’t have to call the police in the first place.”

There’s an appetite for that in Minneapolis. Betty Davis, a chemical-dependency technician who lives in nearby St. Paul, is eager for the Minneapolis city council to move ahead. “Do something: classes, seminars, something in the community so we know how to step in,” she says. “Educate the community. Get it together. One chord.”

The challenge—for Minneapolis, or whatever jurisdiction fashions what will amount to a test run for the new paradigm—is to find both the language and the structure that works for everyone. There is an elegance to the idea: use the mantle of “public safety” to funnel resources into the community that needs them, and knows how to keep itself safe, and in doing so will make others feel safe as well. No less important, “the state” can begin to remake its historical dynamic with the Black community, by leading with something other than a gun.

In researching his book Uneasy Peace, which seeks to account for the dramatic decline in urban crime rates over the past two decades, Princeton sociologist Patrick Sharkey came upon one telling contributor: for every community nonprofit set up to confront violence, the local murder rate dropped by about 1%.

“I think a model of public safety that starts with care or concern is exactly right,” says Sharkey, “but it also has to be carried out by people who understand how to create safe streets, who are trained, who are trained to shift their work and their practices so that they’re not dealing only with people who walk through their doors but are instead looking out and saying, Where are the problems in this community?”

On those safe streets, nonprofit organizations, local community groups and neighborhood leaders will be empowered to take charge of situations. A social worker with proper training and funding will respond to a non-violent call, instead of a cop with a badge and a gun. If there’s fear of potential violence, an officer will accompany the social worker and be available should the need arise, perhaps waiting at the curb. And if the streets are ever going to be truly safe, while all this is going on, people motivated by care and concern will be working behind the scenes to address the underlying issues that gave rise to the problem in the first place.

“There are going to be lots of places where it’s a disaster, I’ve no doubt. And there are going to be places where there are really bad outcomes,” Sharkey says. “I think what we have to recognize is—that’s already happening. That’s going on right now. We’re not working toward a utopia. We’re working toward a different model that will, on average, produce different outcomes.”

After hundreds of years of cities and their police departments doing the same things and getting the same results, any different outcome is a big ask. But it’s a future worth imagining. —With reporting by Anna Purna Kambhampaty

Correction, Aug. 17:

The original version of this story misstated when Joseph Wysocki became police chief in Camden. It was in 2019, not 2015.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Josiah Bates/Camden, N.J. at josiah.bates@time.com