No one was waiting with bated breath for the results of Venezuela’s legislative election on Sunday. Seven years into his presidency, authoritarian leader Nicolás Maduro was widely expected to take control of Venezuela’s opposition-held parliament.

And he did. In a vote condemned by electoral observers and boycotted by the four main opposition parties, a coalition of the ruling Unified Socialist Party (PSUV) and other pro-government parties won a landslide victory, with 67.6% of the vote, according to Venezuela’s electoral service. On Wednesday authorities said that translated into 253 seats – 91% of the seats available in the National Assembly.

U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo on Monday described the poll as “a political farce intended to look like legislative elections” and “an attempt to install a complicit, puppet National Assembly, beholden only to Maduro.”

Though anticipated, the results have created a new era of uncertainty for the opposition movement seeking to oust Maduro.

Before this weekend, the National Assembly was considered the last democratically-elected institution in Venezuela, having been chosen by voters in 2015 before the worst of Venezuela’s political and economic crisis set in. Though Maduro stripped the assembly of its powers in 2017, it still plays a crucial role for the opposition. Since February 2019, opposition leader Juan Guaidó has used his role as head of the assembly as the basis for his claim to be Venezuela’s rightful interim president, citing Venezuela’s constitution, which asserts that the assembly’s leader should take charge when the presidency is “usurped”. Almost 60 countries, including the U.S., have backed Guaidó’s claim and recognized him as Venezuelan president last year.

Guaidó was already struggling to maintain momentum for his campaign to oust Maduro after almost two years that have yielded few concrete results in Venezuela and amid the COVID-19 pandemic which has made it harder to organize protests. Losing official control of the assembly has left his claim to be president on even shakier ground and sent Venezuela sliding closer to outright dictatorship.

“I think this is the beginning of the end of Guaidó’s interim presidency and certainly an inflection point for his leadership of the opposition,” says Risa Grais-Targow, Venezuela director at Eurasia Group, a political risk consultancy. “Maduro’s grip on the system is now total.”

How did Venezuela end up in crisis?

Venezuela’s political crisis has developed out of its economic collapse, the worst outside of wartime for any country in almost half a century, economists say. The country’s heavily oil-reliant economy began to buckle in 2014 due to drops in oil prices, economic mismanagement and corruption. Sanctions by the U.S. and other countries have compounded the economic problems. Oil production has now fallen to 363,000 barrels per day—down from 2.9 million in 2013, and Venezuela’s 2020 GDP is just over a third of what it was seven years ago, according to the IMF. At least 3.6 million Venezuelans have fled the country and more than 19 million are in need of urgent humanitarian assistance, according to UNICEF.

As the economic situation got out of hand, Maduro—who took over when Hugo Chavez, the architect of Venezuela’s socialist system, died in 2013—tightened his grip on the country. He has stacked the country’s institutions with supporters, jailed opposition politicians and activists, and cracked down on free speech. Analysts say Maduro has managed to cling to power despite the economic meltdown by granting kickbacks and special privileges to PSUV elites and the upper ranks of Venezuela’s large armed forces.

Read more: ‘We Are Watching Our People Die’: The Human Toll at the Heart of Venezuela’s Crisis

What happened at the legislative elections?

Since Maduro had already created an alternative legislature to take over the functions of the National Assembly in 2017, government critics said Sunday’s elections served mainly as an attempt to legitimize Maduro’s regime. “It’a democratic mirage to snuff out the last glimmer of democracy that remains in the country,” wrote Venezuelan writer Alberto Barrera Tyszka before the vote. The alternative legislature will finish its mandate this month as Maduro-backed candidates claim control of the National Assembly.

The E.U. refused to send a team of electoral observers to monitor Venezuela’s elections because it reported that the minimum conditions needed for a democratic vote were not in place. In June, Venezuela’s supreme court ordered the dismissal of the leaders of two major opposition parties and placed Maduro allies at the parties’ helms instead. Twenty seven opposition parties boycotted the legislative elections, with Guaidó arguing that to participate would legitimize a process that would not be free or fair.

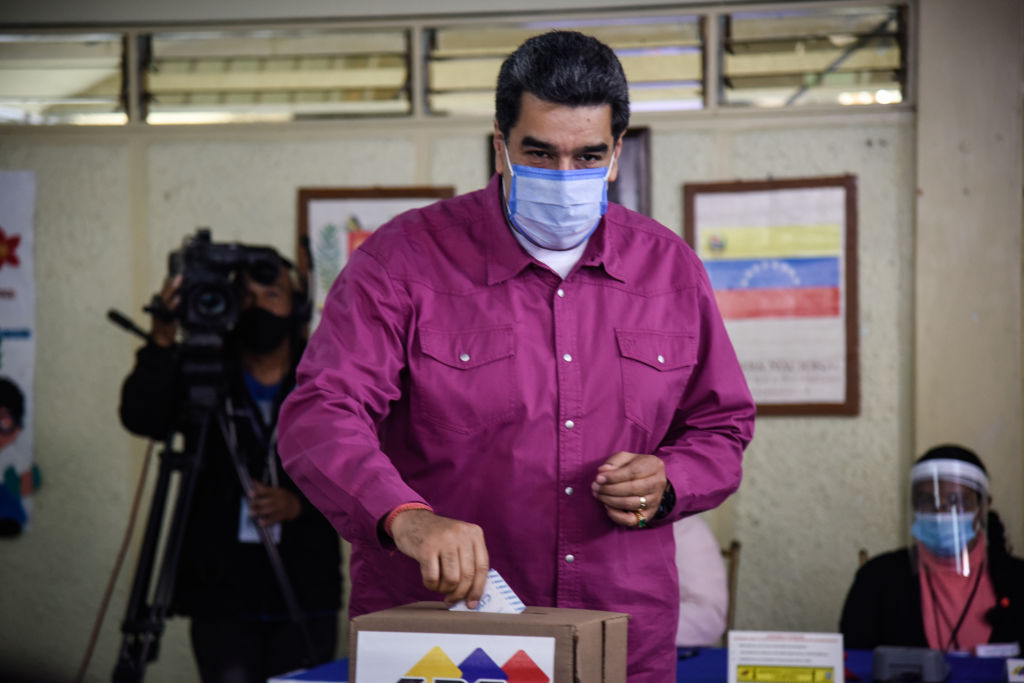

“We’re starting a new cycle of triumph,” Maduro said Sunday after the electoral service confirmed that pro-government candidates had won a majority. Officials put turnout at 30%, while the opposition said only 18.3% of the electorate participated. Both figures would be sharply down from 2015’s turnout of 71%, suggesting increasing disillusionment among voters.

How does it change the balance of power in Venezuela?

Guaidó has pledged to continue in his role as interim president—but when he loses his official standing as National Assembly leader on Jan. 5, it could undermine the legitimacy of his constitutional claim to lead Venezuela.

In a bid to bolster that claim, and as an alternative to the official elections, Guaidó is running a “popular consultation,” ending on Dec. 12, that asks Venezuelans to voice their disapproval of the regime. But Venezuelan journalists say it is unlikely to draw many participants as most Venezuelans feel deeply disconnected from politics amid the desperate situation they face. While Guaidó remains more popular than Maduro, polls show his support has fallen from 61% in February 2019, to just 25% in July this year.

For the international community, Guaidó’s most important source of support, the legislative elections results will create a situation that is “increasingly awkward for everyone,” Grais-Targow says. Countries are unlikely to renege on their recognition of Guaidó in the short-term. The Trump administration has pledged to continue to recognize Guaidó, and advisers to President-elect Joe Biden say he will do the same, according to the Washington Post. But the strength of active international support for Guaidó could begin to wane as his path to ousting Maduro and holding free elections seems increasingly untenable.

Maduro, meanwhile, could be emboldened to crack down on opposition figures. Without their official status as members of the national assembly, former legislators will lose their parliamentary immunity from prosecution, creating the possibility of the pro-Maduro justice system bringing charges against them. Guaidó’s own immunity was stripped in April 2019. His visibility as opposition leader and his international support has so far shielded him from arrest.

What’s next for the opposition’s effort to restore democracy?

These results could spark a major change in direction for Venezuela’s opposition. The unified support that anti-Maduro parties gave to Guaidó in 2019 was a rare phenomenon in Venezuelan politics, where opposition to the governments of first Chavez and then Maduro has historically been fractured. Now, cracks are beginning to show again.

Henrique Capriles, a long-time face of the opposition who was Maduro’s main challenger at 2014 elections, opposed the Guaidó-led plan to boycott the elections. He argued that politicians need to take part in the polls to interact with the public and show that they have not abandoned them, even as they highlight the regime’s fraudulence. Capriles eventually abandoned his efforts to persuade opposition figures to take part, after the government rebuffed his efforts to improve democratic conditions for the election.

Capriles and other opposition figures have in recent months begun to criticize Guaidó’s refusal to stray from his strategy of using maximum international pressure—and increasingly aggressive sanctions—to try to force the Maduro regime out of office. Capriles is pushing a more “incrementalist” approach, Grais-Targow says. “He may pursue some kind of power-sharing agreement—something that’s very different from the zero-sum offer that Guaidó has been pursuing over the last two years.

Divisions may also be opening, analysts say, between the opposition inside Venezuela and more hardline anti-Maduro figures who have fled the country since the beginning of the political crisis, such as Guaidó’s mentor Leopoldo Lopez, who moved to Spain after escaping persecution by the regime and house arrest. Those abroad still back Guaidó’s attempt to force regime change. “That hasn’t worked. Maduro has managed to ride it out, which is actually quite remarkable,” Grais-Targow says. “Now there’s a segment of the opposition that’s looking for maybe more realistic alternatives.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Ciara Nugent at ciara.nugent@time.com