When she walked into the large cell deep inside Venezuela’s most notorious prison in July 2018, Dennysse Vadell could not find her husband. She frantically scanned the faces of the assembled men in dark green uniforms until finally one of them raised his arms and called her name: “Dennysse, I’m here.” It had been less than nine months since masked security agents had stormed a conference room in Caracas and arrested Tomeu Vadell and five other Citgo executives, but he was unrecognizable. The usually robust, 6-ft. 1-in. Louisiana businessman had lost 60 lb., and his skin was tinged with gray after months without sun. “I couldn’t believe it,” Dennysse says. “When I hugged him, he was all bones.”

Nearly two years later, the six men, five of them American citizens, face a danger graver even than their continuing imprisonment in Venezuelan strongman Nicolás Maduro’s El Helicoide prison: COVID-19. Already there have been four cases of the new corona-virus reported in El Helicoide. The men have been trying to protect themselves in a crowded cell with no running water, armed only with undiluted bleach, which burns their hands and releases fumes that worsen their respiratory ailments. For the detained men—weakened by malnourishment and under-lying health conditions—the virus would likely be a death sentence, their families say. “We are all absolutely desperate,” said Carlos Añez, whose stepfather Jorge Toledo is one of the imprisoned Americans.

The coronavirus pandemic is only the latest of the powerful unseen forces that the Texas and Louisiana-based executives have faced during their 28 months in prison. First among them is Maduro’s need for pawns in his long-running political and economic battle with Washington and the Trump Administration, which has called for Maduro’s ouster. Then there are the business interests of the men’s employer, Citgo, the Houston-based U.S. subsidiary of Venezuela’s state-owned oil giant. And then there are the cold-eyed calculations of Maduro’s opponents in Venezuela and abroad, for whom the safety and well-being of the six men are not the top priority.

The result, the families of the men say, has been a lack of urgency to get their husbands and fathers home. Despite well-intentioned efforts by some lawmakers and legal advocates to rally support, the case has remained largely out of public view. Citgo has failed to take concrete action to free its detained executives or to offer more than token support, according to the families. A meeting with Vice President Mike Pence last April amounted to little more than a “photo op,” they say.

Now, with their court hearings postponed at least 18 times but no date set for their trial on charges of embezzlement, the families say that the COVID-19 pandemic might offer an unexpected opening. Already other countries including Iran have released U.S. detainees on humanitarian grounds. On March 19, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo put out a statement calling for the release of the “wrongfully detained men,” who “face a grave health risk if they become infected.” The families have begged U.S. officials to use any leverage. “This is life or death,” says Vadell’s daughter Cristina. Now the families are left with the hope, and the fear, that the COVID-19 outbreak could bring the saga of the Citgo Six to an end, one way or another.

The weekend before Thanksgiving in 2017, the six businessmen were summoned to attend an unusual last-minute meeting in Caracas. Nelson Martinez, the president of Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. (PDVSA), which owns Citgo, was demanding to see the company’s vice presidents to discuss budgets. All six men had been promoted to these executive positions in the preceding months, and the company insisted that they fly there together, chartering one of Citgo’s company planes. Before he left, Vadell promised his wife he’d be home in Lake Charles, La., in time to roast and carve the turkey, his favorite tradition.

Just a day into what was supposed to be a three-day business trip, armed security agents stormed the conference room where they had gathered. Hours later, Venezuela’s chief prosecutor, Tarek William Saab, announced that the six men had been arrested as part of a probe into “corruption of the worst kind.” On state television, he held up a document he said proved that the executives had sought to profit from a deal to refinance $4 -billion in Citgo bonds by signing off on terms that had not been approved and were unfavorable to Venezuela. The refinancing negotiations were approved by PDVSA’s board in June 2017, according to documents reviewed by TIME, and most of the executives held roles that would not even have made them privy to such talks, their lawyers say. A deal was never signed.

The arrest of the Citgo Six occurred as Maduro, who was facing an election, sought to consolidate his control over the crown jewel of the Venezuelan economy overseas. By purging the American company’s leadership and arresting five U.S. citizens and one U.S. permanent resident, he was also hitting back at Washington for its punitive economic sanctions. The day after their arrest, Maduro declared that the arrested executives were “going to be judged for being corrupt, for being thieves, traitors to the fatherland,” vowing they would be “properly imprisoned and should go to the worst jail that Venezuela has.”

That threat quickly became a reality, according to those who have visited the men in detention in Caracas. The men were taken to a military prison run by the Venezuelan intelligence service, known as the Dirección General de Contrainteligencia Militar (DGCIM). Pompeo has denounced the DGCIM’s leadership for “gross violations of human rights,” and a recent U.N. report accuses it of being “responsible for arbitrary detentions, ill treatment and torture of political opponents and their relatives,” including electric shocks, suffocation with plastic bags, water-boarding, beatings, stress positions and exposure to extreme temperatures.

The Citgo employees have mainly been held two floors below ground in an overcrowded basement cell, according to family members who have visited them. For much of their detention, the lights have been left on 24 hours a day. In a country plagued by food shortages, their diet often consisted of rice and pasta that family members estimated totaled only 600 calories a day. The facility seems to change the rules about visits and access to their belongings almost weekly.

Phone calls home are sporadic, often lasting between 30 seconds and two minutes before the line goes dead, according to the families. Sometimes that is just long enough for the men to list what items they urgently need. Everything from safe drinking water to food and medicine has to be paid for and provided by the families. They worry much of it is being confiscated by the guards. Even worse, over the course of their long detention many of the men began to develop health conditions, including bronchitis, heart issues and complications related to diabetes.

While Citgo publicly expressed its concerns after the arrests, family members say the company did little to provide clarity or support for the men’s families at home. They had to find out about the arrests from friends and the news, not the company. In the following days they tried and failed to get Citgo’s lawyers on the phone to find out what the company was doing to help their detained executives. Even though the businessmen are technically still employed by Citgo—in phone calls with their children, some of the men weakly joke that they’re “still on a business trip”—the company stopped paying their salaries six months after they were arrested, the families say.

The situation has forced some of the families to burn through the men’s retirement savings and even sell their homes in order to stay afloat while paying for everything the men need in Caracas. Maria Elena Cardenas, whose husband Gustavo is among the imprisoned executives, is able to take only part-time work because she has to take care of her special-needs son Sergio. She has had to fall back on church donations in Houston for food and has had to apply for food stamps to pay medical bills.

Citgo says it is supporting U.S. efforts to secure the release of the men, who they refer to as “our colleagues,” but did not provide details. “CITGO believes that the detention of these men violates their fundamental human rights, including the right to due process under law,” the company said in a statement. “We continue to support the detainees’ families, and we are grateful for the efforts of this Administration and lawmakers on both sides of the aisle to bring these men home.”

Throughout this ordeal, the families were advised to stay quiet. In meetings and calls with State Department officials, they were assured that the U.S. was doing everything it could to secure their release. But they could see little progress, and few specifics were shared with them. “We don’t know with any level of detail whatsoever what the U.S. is doing,” Añez said.

Current and former officials say that such delicate diplomacy is best undertaken behind the scenes. “Maduro takes Americans as a pawn in a chess game that he’s playing in trying to survive as a dictator,” says Fernando Cutz, who worked on the National Security Council under both the Obama and Trump administrations. “The U.S. can sanction him and his whole economy, and there’s not a whole lot he can do back at us. It’s a rare piece of leverage. It’s very tough, but often the best strategy [in these cases] is to work behind the scenes.”

State Department officials, including those in the the Office of the Special Presidential Envoy for Hostage Affairs, have worked “both directly and through intermediaries” to press the Maduro regime to release the men, a spokesperson for the State Department Bureau of Western Hemisphere Affairs tells TIME.

Representative Pete Olson, a Texas Republican who counts three of the detained men as constituents, similarly says that “most of the diplomacy to secure their release is not happening in front of the media for security reasons,” although he acknowledged “it seems for every two steps forward we take toward their release, we then take one step back.”

But over time, the families have grown increasingly frustrated. They say they don’t understand why Trump and other officials, in their frequent denunciations of Maduro as a dictator and expressions of support for the suffering of the Venezuelan people, have rarely mentioned the five U.S. citizens imprisoned there. While the Trump Administration touted its record of returning American hostages, including from Venezuela, their detained family members seemed to have been forgotten. Constant turnover in the State Department and National Security Council meant that the U.S. officials familiar with their case kept leaving their positions, forcing the families to explain their case to a new official all over again.

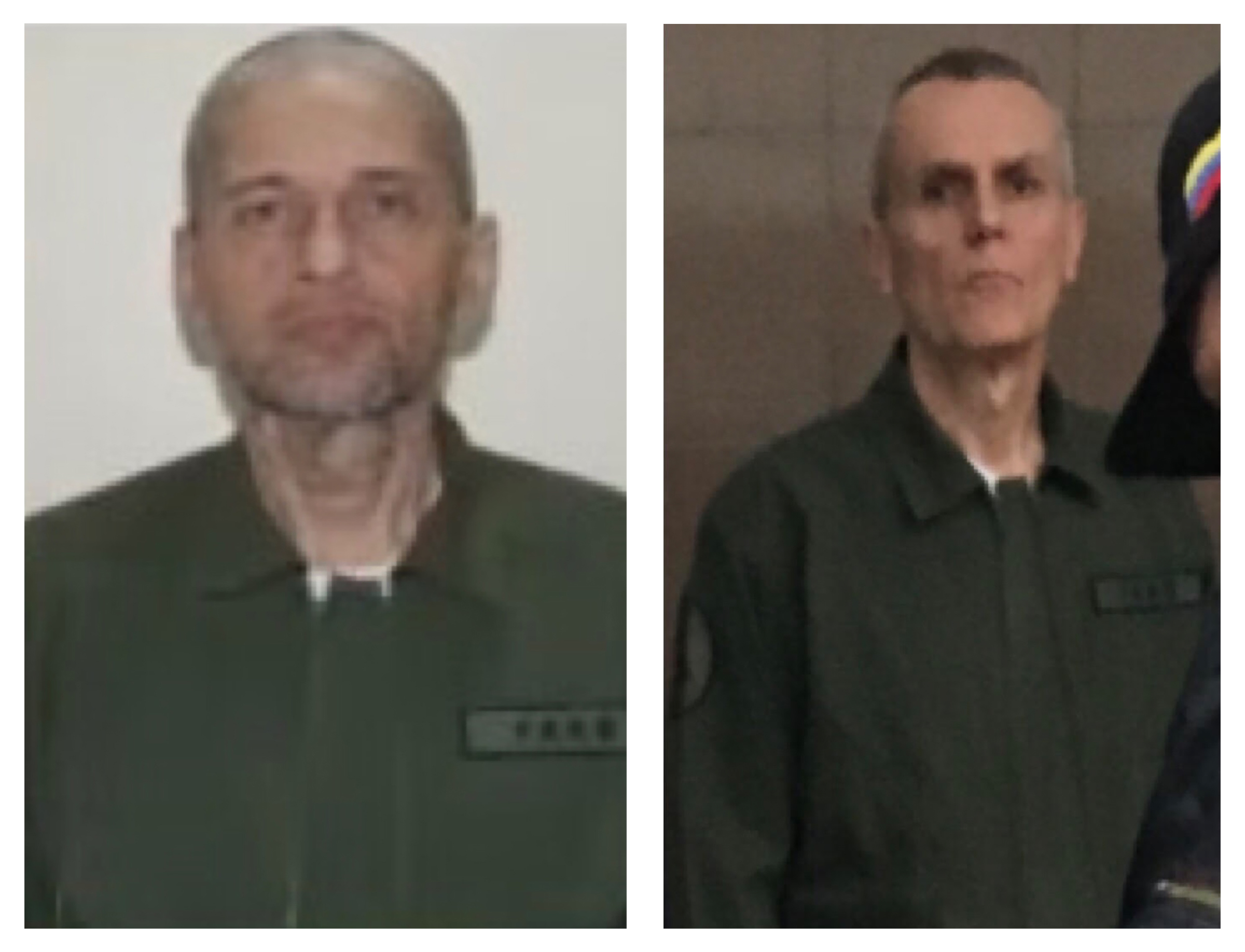

All the while, their loved ones were deteriorating. The drastic physical change is evident in photos from inside the prison obtained by TIME, showing the men gaunt with shaved heads. “The shock of seeing him like that, in deplorable conditions, was indescribable—an innocent person, an honest person who has never stolen as much as a pencil from his office,” said Cardenas, who managed to arrange a trip from Houston to Caracas in summer 2018 to visit her husband Gustavo with her children.

In January 2019, the political situation in Venezuela finally seemed to shift. Charging that Maduro’s re-election the previous year had been illegitimate, opposition leader Juan Guaidó declared himself the country’s rightful interim President, and he was backed by the U.S. and dozens of other governments.

But Guaidó turned out to be no help for the detained Americans. The opposition is treating the men with indifference, at best. Guaidó officials tell TIME it was just “one of so many cases that show the lawlessness of the regime.” Says Gustavo Marcano, the minister counselor to the Venezuelan opposition’s envoy to Washington: “No doubt some of them are people who are victims, but this is not a separate case, it’s part of the drama that millions of Venezuelans are living.”

Nor has Guaidó’s success at winning control of Citgo—depriving Maduro of that prize, with the help of a U.S. court—changed the company’s posture toward the families. It spent around $2 million a year in both 2018 and 2019 on Washington lobbyists to represent company interests, according to filings. The families say the company has made no visible efforts to push for the detained Americans’ release.

In March 2019, the White House reached out to the families of the Citgo executives. Pence hosted the families at the White House, reading out the names of the six men as if in a solemn prayer. “The names of all of them deserve to be known to the world,” Pence said. The Vice President finally uttered the words the families had waited 18 months to hear from a high-profile U.S. leader, promising that the Administration would “use all means at our disposal” to secure their release. “We are with you, we are going to stand with you until your loved ones are free, until Venezuela is free,” Pence told them. He said Trump was looking at a “broad range of options.”

A year later, little seems to have come from that meeting. The families compare the nice talk from the Administration with the results the President got in other cases, especially that of Joshua Holt, a Utah man who was held for more than two years in a Caracas jail for allegedly stockpiling guns and was personally welcomed home by Trump last year. “The President and his team were very engaged and succeeded in bringing him home,” said Jason Poblete, a Washington, D.C., lawyer who represents the Vadells.

The families of the Citgo executives say they feel painfully aware that the same efforts aren’t being made on their behalf. They worry it’s due to a bias because they’re Venezuelan American, making them second-class citizens when it comes to urgency for the U.S. government, and the perception that the men must have been complicit in something illegal. “As American citizens, you never think something like this could happen to you,” says Vadell’s daughter Veronica. “You think it would be like in the movies, where the U.S. would send a rescue team or do everything possible to get you out. But soon you realize it’s all just being managed by human beings, and that no one is going to help you, nothing is going to happen if the political will isn’t there.”

Last summer, the families watched in disbelief as Trump repeatedly tweeted about the detention of American rapper A$AP Rocky after he was accused of assault following a fight in Stockholm. When the President then dispatched his special envoy for hostage affairs, Robert O’Brien, to Sweden to oversee his release, it felt surreal. For them, it has been “a fight of 16 months from when they took my father hostage to get their office to talk to us,” Cristina Vadell tells TIME. “This rapper was in Swedish jail, in a country that unlike Venezuela has an actual legal process, and the U.S. sends O’Brien there to negotiate for his release in person,” she says. “Meanwhile the government is leaving our father, who is an innocent 60-year-old man, out to dry.”

In December last year, soon after the men had marked a third Thanksgiving in prison, there seemed to be a breakthrough when they were suddenly released on house arrest in Caracas. Despite the armed guards outside the doors, who came in every four hours to take photos of them, their families hoped it was a step in the right direction. In FaceTime video calls, they saw the men were regaining some weight and their hair was growing back.

But in late January, rumors began to circulate in Spanish-language media that a high-profile meeting between Trump and Guaidó was in the works. Alarmed, legal advocates for the Citgo Six quietly and repeatedly warned the Trump Administration that if such a visit wasn’t handled properly, the Maduro regime would seek political retribution. But Trump proceeded. He invited Guaidó as his guest to the Feb. 4 State of the Union address, where he touted him as the “true and legitimate President of Venezuela.”

The following day, just hours after Trump received Guaidó at the White House, the six American executives back in Caracas were seized and again imprisoned. Jorge Toledo was eating dinner with a friend when security agents came in and told him they were taking him to a medical examination. His friend later told his family that, “He turned pale, like we was going to pass out,” recalls Añez. When Toledo tried to pack some belongings, he was told he would be coming right back. That evening, he and the other Citgo executives were taken to El Helicoide, a prison inside a massive pyramid-shaped building that was originally built to be a shopping center. It would be 42 days before their families would hear from them again. When they finally received the phone call, the global coronavirus pandemic was already looming over Venezuela.

Now, family members and legal advocates say the COVID-19 outbreak could help spur some action as the U.S. has launched a broader push to bring home Americans detained abroad on humanitarian grounds amid fears that the virus could lead to their deaths. “People are starting to relate to our case in a way they never would have,” Veronica Vadell says.

The families hardly dare say it, but quietly they hope that there may be a silver lining to the scourge that is sweeping the world. Venezuela is bracing for the terrifying effects of the disease. Maduro announced a nationwide lockdown on March 16, and epidemiologists have warned the country will be especially vulnerable to the outbreak because of its crippled health system that is already short on hospital beds and basic medical supplies.

Perhaps, the families say, the outbreak will spur a moment of humanitarianism in the leadership of the country. If it doesn’t, they fear, the disease could just as likely be the regime’s indirect death sentence for six innocent victims of a global power struggle.

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now, You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time