In Lafayette Park, just steps away from the White House, a wealthy hotelier ran a second business selling enslaved men and women to the highest bidder.

He kept them in a brick cell beside his mansion, and at night an observer recalled hearing “their howls and cries.”

Today in the park there is no plaque, no bench and no monument, to paraphrase Toni Morrison, to memorialize the human lives brutalized there throughout much of the 19th century. After a hard-fought Civil War, the institution of chattel slavery was legally abolished as the U.S. nominally attempted to make racial violence a thing of the past. These days, in the public space situated across from the White House, one is likely to encounter instead an odd mix of office workers on lunch break and MAGA-hat-wearing tourists mingling around the hotelier’s former mansion, known as Decatur House.

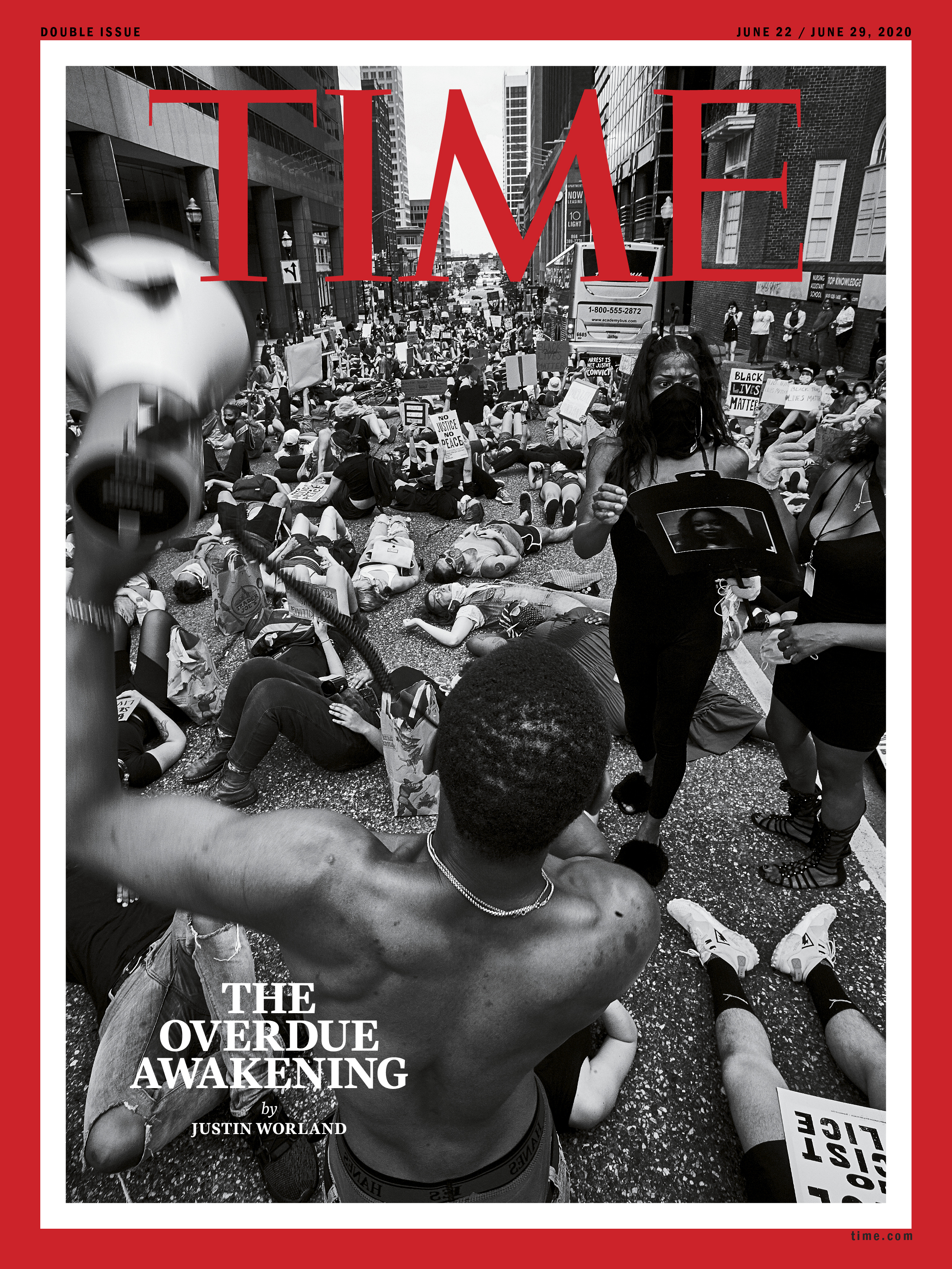

Or at least, that was the scene before the past three weeks turned Lafayette Park into a crucible for the fight over the still-present legacy of slavery in America: systemic racism.

Just before 7 p.m. on June 1, a deployment of local, state and federal forces, armored head to toe in riot gear, unleashed rubber bullets and sprayed tear gas onto a crowd of peaceful demonstrators gathered in the park to protest under the mantra “Black Lives Matter.” Moments after the crowd was forcibly dispersed, screaming as their eyes burned from the gas, President Donald Trump strolled out of the White House flanked by senior members of his Administration, triumphantly holding up a Bible so the press could snap a few photos.

Since then, the debate over systemic racism has spread across the nation and around the world. Trump’s Administration has repeatedly denied that discrimination against black Americans is embedded in the political, economic and social structure of the country. Trump believes there are “injustices in society,” his press secretary said, but she brushed aside the notion that antiblackness is intrinsic to U.S. law enforcement. His National Security Adviser, Robert O’Brien, said racist police are just a “few bad apples,” adding, “we need to root them out.” Attorney General William Barr warned against “automatically assuming that the actions of an individual necessarily mean that their organization is rotten.”

But, for all that’s good about America, something is rotten. The protesters in Lafayette Park on June 1 may have been galvanized by the disturbing video of the murder of George Floyd, suffocated to death beneath the knee of a Minneapolis police officer just a week prior. But at the core of their movement is much more than the outrage over the latest instances of police brutality. Centuries of racist policy, both explicit and implicit, have left black Americans in the dust, physically, emotionally and economically. The U.S. may think it has brushed chattel slavery into the dustbin of history after the Civil War, but the country never did a very good job incinerating its traumatic remains, instead leaving embers that still burn today: an education system that fails black Americans, substandard health care that makes them more vulnerable to death and disease, and an economy that leaves millions without access to a living wage.

Politicians, activists and everyday people can and should debate what to do about this reality, but it is a reality, one evident in volumes of data, research and reporting, not to mention the lived experience of millions of African Americans each and every day. What is helping make this moment historic is that over these past weeks and months, much of the rest of the U.S. appears to have woken up to this truth too.

The crowds of protesters from Seattle to Miami include not just black youth, but a diverse array that looks something like the country itself. In 2015, in the wake of unrest in Ferguson, Mo., just half of Americans said they believed racial discrimination to be a “big problem,” and, in 2016, only a third considered black Americans more likely to suffer from police brutality, according to Monmouth University polling. Today, by contrast, more than 75% of Americans say discrimination is a big problem and 57% understand that African Americans are more likely to suffer from police violence than other demographic groups are, a recent Monmouth poll found.

More broadly, the notion of “systemic racism,” once confined to academic and activist circles on the left of the spectrum, has become the phrase du jour, with Google searches for the term rising a hundredfold in a matter of months and mainstream conservatives like former President George W. Bush joining historically moderate Democrats like Joe Biden in embracing the term to call for a national reckoning.

This spreading recognition highlights an ever starker dividing line in America. On one side, a growing majority of the country is increasingly ready to repudiate its history of structural racism. On the other, many of those in power, especially at the White House, are eager to deny it. This is no surprise. By definition, systemic racism is embedded deep and wide across American society and, therefore, can’t easily be rectified. But, for many of those who have spent their lives fighting for racial justice, this is a moment of reckoning that has been a long time coming. “Not everything that is faced can be changed,” James Baldwin, the black author and activist wrote in the manuscript of his memoir Remember This House, “but nothing can be changed until it is faced.”

The origins of America’s unjust racial order lie in the most brutal institution of enslavement that human beings have ever concocted. More than 12 million Africans of all ages, shackled in the bottom of ships, were sold into a lifetime of forced labor defined by nonstop violence and strategic dehumanization, all cataloged methodically in sales receipts and ledgers. Around that “peculiar institution,” the thinkers of the time crafted an equally inhumane ideology to justify their brutality, using religious rhetoric in tandem with pseudoscience to rationalize treating humans as chattel. After the Civil War, the arrangements of legal slavery were replaced with those of organized, if not strictly legal, terror. Lynchings, disenfranchisement and indentured servitude all reinforced racial hierarchy from the period of Reconstruction through Jim Crow segregation and on until the movement for civil rights in the middle of the 20th century.

That’s the ugly history most Americans know and acknowledge. But systemic racism also found its way, more insidiously, into the institutions many Americans revere and seek to safe-guard. Established in the 1930s, Social Security helped ensure a stable old age for most Americans, but it initially excluded domestic and agricultural workers, leaving behind two-thirds of black Americans. Federal mortgage lending programs helped white Americans buy homes after World War II, but black Americans suffered from a shameful catch-22. Federal policy said that the very presence of a black resident in a neighborhood reduced the value of the homes there, effectively prohibiting African-American residents from borrowing money to buy a home. And sentencing laws of the past several decades meant that poor black Americans were thrown in prison for decades-long terms for consuming one type of cocaine while their wealthier white counterparts got a slap on the wrist for consuming another.

There’s a straight line between these policies and the state of black America today. The lack of Social Security kept black Americans toiling in old age or forced them to the streets. The obstruction of black homeownership, among other factors, has left African Americans poorer and more economically vulnerable, with the average black household worth $17,000 in 2016 while the average white household was worth 10 times that. “Tough on crime” sentencing policies have ballooned the black prison population, torn apart families and left millions of children to grow up in single-parent homes.

This systemic discrimination is also a matter of life and death, and police violence, which kills hundreds of African Americans every year, is just the start. Look no further than the coronavirus pandemic. The neighborhoods in which black Americans often find themselves confined by a legacy of discriminatory policy are rife with pollution and, in many cases, lack even basic options for nutritious food. This leaves residents more likely to suffer from health ailments like asthma and diabetes, both of which increase the chances of poor outcomes for those infected with COVID-19.

To actually capture all the ways in which the system is skewed against black people would require tome upon tome. But even a short list feels very long: black women are three to four times as likely as white women to die in childbirth, in part because of a lack of access to quality health care; black children are more likely to attend underresourced schools, thanks to a reliance on local property taxes for funding; black voters are four times as likely as white voters to report difficulties voting or engaging in politics than their white counterparts, in part because of laws that even today are designed to keep them for exercising their basic democratic rights; millions more have been disenfranchised because of felony convictions; hurricane flooding has been shown to hit black neighborhoods disproportionately.

Jeh Johnson, a lawyer who served as Obama’s Homeland Security Secretary and was recently tapped to help New York state courts conduct a racial bias review, explained it flatly. “Defined broadly enough, one could say that there’s systemic racism across every institution in America,” he told CNN recently.

With this in mind, it may come as little surprise that black Americans took to the streets in protest following the murder of George Floyd. Nearly 17% of African Americans are unemployed. When the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported a surprise up-tick in jobs in May, the unemployment rate for African Americans in particular nevertheless remained on the rise. In the U.S., black Americans are dying from COVID-19 at twice the rate of their white counterparts. In some states, the disparity is even sharper.

What’s perhaps more surprising is that the rest of America is apparently waking up to these realities. For decades, the truth of systemic racism has always been swept under the rug, lest it make white Americans uncomfortable and hurt the electoral chances of those with the power to address it. In 1968, the Kerner Commission, initiated by President Lyndon Johnson to study unrest in American cities insisted that “white society is deeply implicated in the ghetto. White institutions created it, white institutions maintain it, and white society condones it.” The results of the Commission were largely ignored.

During Barack Obama’s first presidential campaign, many Americans were outraged when news broke that the Rev. Jeremiah Wright, Obama’s pastor, had uttered the words “God damn America” for “killing innocent people,” “treating our citizens as less than human” and failing “the vast majority of her citizens of African descent.” Obama condemned the comments and reminded the public that, actually, the U.S. had made great progress, even while acknowledging far more was needed.

Today, the conversation is different, and one wonders whether such remarks, as salient now as they were then, would still be met with disavowal. The U.S. cannot deny what is plainly before its eyes. Shocking videos depict George Floyd and Ahmaud Arbery murdered in broad daylight. Tens of thousands of black lives have been taken by the coronavirus. And, in the midst of all this, the President fans the flames of racial tensions with dog whistles so unsubtle that even the most skeptical can hear them.

In urban centers, black and white protesters have come forward together in defiance, joined by allies like GOP Senator Mitt Romney and longtime Koch Industries executive Mark Holden. In predominantly white cities across the country, white Americans have shown up by the thousands in solidarity. Even small towns in rural parts of the country have joined in the protests.

A lot would need to change to address such deeply rooted bias. The first test may come this year as momentum grows in city halls, statehouses and Washington, D.C., for reforms to root out police brutality, perhaps the most flagrant and visible injustice. “Justice for George is something that many people who were killed through brutality of the police never get,” says Benjamin Crump, a civil rights lawyer representing Floyd’s family. “And that is a transformative justice, a systematic reform across the board.”

Whatever the progress transpires in the coming months, the U.S. still has a long way to go. Last year, I happened to find myself in both Berlin and Charleston, S.C. In Berlin, where Adolf Hitler planned and oversaw the extermination of millions of Jews, it felt as though I couldn’t walk a few blocks without a memorial atoning for that sin. In Charleston, I fell asleep on a picturesque beach, only to learn later that the site was a key node in the Atlantic slave trade, where traders imported 40% of enslaved Africans who came to North America. I spent the rest of the day feeling sick to my stomach, disgusted at the possibility that I had enjoyed a leisurely nap where, perhaps, one of my ancestors endured one of the most gruesome of human institutions.

Awakening can be painful. But in America, a reckoning is overdue.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Justin Worland at justin.worland@time.com