Barry Jenkins doesn’t just love James Baldwin–he calls the 20th century literary lion his “personal school of life.” But Baldwin’s work was long out of reach for storytellers like him because the writer’s family has been, since his death in 1987, reluctant to grant the rights to adapt his work.

Not so any longer. This month Jenkins brings to the screen an adaptation of Baldwin’s 1974 novel, If Beale Street Could Talk, marking the first English-language film based on one of the author’s published works. It would be easy to assume that Jenkins received the keys to the Baldwin kingdom thanks to the Best Picture statue his 2016 drama, Moonlight, won at the 89th Academy Awards. But Jenkins, who discovered Baldwin in college at the urging of an ex-girlfriend, had already adapted Beale Street well before Moonlight was filmed–without knowing whether he’d be able to secure the rights. Baldwin’s family, on the strength of that screenplay and Jenkins’ sole feature-length credit–his 2008 debut, Medicine for Melancholy, made for only $15,000–took a risk of their own and said yes.

It paid off. Jenkins’ adaptation, which stars KiKi Layne and Stephan James as Tish and Fonny, soul mates kept apart by a rotten, racist criminal-justice system as they await the birth of their child, has met with shimmering reviews and already begun collecting honors, in particular for Jenkins’ screenplay and a supporting turn by Regina King as Tish’s mother.

“I just wanted to send people back to James Baldwin,” says Jenkins, 39, over green-lentil soup at a Provençal bistro just blocks from Manhattan’s Washington Square Park, where early in the movie Tish and Fonny cavort, giddy with love, unaware of the bitter spell that awaits them. “I’m still trying to understand this new relationship I have with him, to have my voice so aligned with his.”

Jenkins, whose thick plastic glasses and chunky navy cardigan project a nerdy-chic aesthetic, is aligned with Baldwin in more ways than one. Both write from perspectives outside their own. Both amplify voices that are often marginalized in our society. And most of all, both tell stories about love–romantic, filial, fraternal–that transcend the obvious.

With Moonlight and now Beale Street, Jenkins cements his status as one of the most vibrant visual storytellers of our time and also one of the most crucial voices. His three features could be categorized by the social issues they grapple with–gentrification in his debut; the intersection of sexuality, race and class in Moonlight; and the racism that corrupts American law enforcement in Beale Street–but Jenkins doesn’t see it this way. “I’ve never considered myself making capital-I issue movies,” he says.

For him, the story begins with humans and ripples out from there. Those humans are imbued by his touch with a dignity and humanity rare for Hollywood, rarer still for characters like Moonlight’s Chiron, a poor black boy growing up to realize he is gay, or Fonny, a young artist entangled in a system that has no regard for his dreams. Many filmmakers tell great stories, but Jenkins trades in an increasingly rare quality in our divided America: empathy.

You know you’re watching a Barry Jenkins film when you find yourself wanting to press pause every few minutes, freeze the frame and hang it over your couch. His camera lingers on a face seconds longer than you’re used to, asking you not just to look but to see. The colors–the inverted yellows and blues of Tish’s and Fonny’s clothes when we first meet them walking along a wooded path in Harlem or the shades of cerulean reflecting off a boy’s skin as he stands before the ocean in Moonlight–look too lush to be true, but their brilliance feels wholly earned.

Yet in Jenkins’ dreamlike films, his characters face nightmarish realities. Fonny is falsely accused of rape and incarcerated after a racist cop targets him, leaving a pregnant Tish to fight for his release. The injustices people of color face at the hands of law enforcement are laid bare by the film’s most harrowing scene, a conversation between Fonny and Daniel, an old friend he’s run into, played by Atlanta’s Brian Tyree Henry. Daniel has just been released from prison for stealing a car, despite the impossibility of his guilt–he doesn’t even know how to drive. As the men drain one beer, then another, Daniel makes plain his anguish. He has his freedom, but he will never again feel free.

Henry attributes the scene’s power to the intimacy Jenkins created on set. “Usually you can see the director in front of you, the monitor, the boom mic,” he says. “But he removed all those elements and set them on the outside of that room. It was just me and Steph at the table.”

Jenkins toyed with the idea of spelling out the story’s connection to the present. “But it seemed to me there was an implicit power in allowing it to remain set in the early 1970s,” he says, “and to illustrate how pervasive these problems have been and how little we’ve done to correct them.” Might that lead audiences to see the tale as squarely situated in the past tense? Sure, says Jenkins. But only if they haven’t absorbed story after story of unarmed black men killed by police, not to mention untold others whose lives have been upended by the twin forces of structural racism and mass incarceration.

“Could we have put a coda with all those young men?” Jenkins asks. He shakes his head. “It would have been too many men to name. It would have been too many men to name.”

In the backyard of the housing project where Jenkins grew up, in the Liberty City section of Miami, stood a portal to other worlds: a satellite dish that craned its neck this way and that so that Eddie Murphy might be transported into a little boy’s living room. Recalls Jenkins: “Back in those days, you had to literally press a button and you’d run outside and watch as the dish pivoted and turned.”

Jenkins describes his upbringing as “difficult” and “chaotic.” His mother had a “raging drug addiction”–she was half the inspiration, along with the mother of his co-writer, Tarell Alvin McCraney, for Naomie Harris’ Oscar-nominated turn in Moonlight. His siblings were a decade older, and he was often alone. “I closed in on myself, creating a cocoon,” he says.

That cocoon began to open up, if only slightly, when he left for Florida State University, where he studied film. After graduating, he moved to Los Angeles for a gig at Oprah Winfrey’s Harpo Films, but 18 months in, he experienced a crisis of confidence. He made his way to San Francisco, where he scrounged up enough to make a feature, Medicine for Melancholy, about strangers who spend the day together after a one-night stand. The movie screened at several film festivals, where it won over critics.

But Jenkins turned to advertising, still unsure of his potential. Five years had passed, and he knew that in order to create again, he needed a change of scenery. He bought a ticket to Brussels. “Four days in, I finished the first chapter of Moonlight. I was like, Hang on, wait a second. I wrote 40 pages in four days. That’s insane.” Then he jetted to Berlin and churned out the adaptation of Beale Street in a brisk four weeks. He came home, a screenplay in each hand.

Moonlight went on to make history, although not exactly in the way Jenkins might have imagined. During the 2017 Oscars, after accepting the trophy for Best Adapted Screenplay alongside McCraney, he became the first director ever to fall victim to a backstage envelope mix-up. Presenters Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway were handed the wrong envelope and announced the Best Picture as La La Land. That movie’s producers got two minutes into their thank-you’s before informing the audience that there had been a mistake: Moonlight had won.

The win was a triumph for Moonlight–which, with its $1.5 million budget and lack of star wattage, was among the lowest-grossing winners ever and the first winner to center on the life of a gay protagonist. But the chaos of “Envelopegate,” as it came to be known, overshadowed the simple fact of the film’s much deserved win. Accidental as the error may have been, it felt to many like a glaring commentary on the unbearable whiteness of Hollywood.

Nearly two years later, Jenkins is on the campaign trail again with Beale Street. But this time, it’s different. With Moonlight, no one expected much, least of all Jenkins, who didn’t even realize he was campaigning until halfway through the campaign. “This time there’s this expectation to prove that the thing before is legit,” he says. “Added to that, I’m not the only person who adores James Baldwin.”

If Beale Street should bring Jenkins back to the Dolby Theatre in February, he’s more concerned with Baldwin’s legacy than his own. “The higher the profile of this film, maybe somebody goes, ‘Who is this James Baldwin? I really like that movie. I want to read his work.'”

Jenkins’ adaptation arrives at a moment when Baldwin’s cultural cachet is so great, it borders on trendy: his words circulate as memes on social media. The moment is overdue, to Jenkins’ mind, but also troubling. “It’s almost like those Che Guevara T-shirts,” he says. “Is he going to end up sold in shopping malls? Where is that money going to go?” Jenkins can control only so much. But when it comes to what he can–doing justice to the work in a new medium–Baldwin fans can trust his steady hands.

Jenkins remembers the day The Color Purple came out in theaters, in 1985. “It was a massive event for my family,” he recalls. Until she died, his grandmother had a cross-stitch of Whoopi Goldberg as Celie Harris, sitting in a rocking chair in Steven Spielberg’s adaptation of Alice Walker’s Pulitzer Prize–winning novel.

Three decades later, a white man helming a story by and about black women would be met with extreme suspicion. The debate over who is allowed to tell which stories is far from settled. Jenkins laughs, thinking back on “simpler times.” “My grandmother didn’t give a damn” who directed it, he says. “She just wanted that story that had meant so much to her.”

Today movies and shows are problematized before they’ve even become available for public consumption. “We live in a time where we feel like everything can be unpacked,” says Jenkins. “‘Unpacking’ is becoming an industry in and of itself.” At best, this atmosphere holds creators accountable for their stories. At worst, it burdens the artist and renders audiences unable to engage with the art.

Jenkins should know. Even before Beale Street premiered, some expressed concern about the harm a story about a false rape accusation could do in the #MeToo era, when survivors of sexual assault are finally beginning to be believed. On the last day of preproduction, the Harvey Weinstein scandal broke. As the story’s volume increased, Jenkins made adjustments, ensuring that the woman who accuses Fonny is not presented as an antagonist and that the audience never doubts the fact of her assault–only that she points her finger at the right man.

Like its source material, which is narrated by Tish, the movie is told from her perspective. “I’m not a black woman,” says Jenkins. “I understood that I needed to listen to all the black women involved in making this film.” When he adapted Moonlight from McCraney’s play, the playwright, who is gay and wrote from his own experience, was his collaborator. Here, Jenkins engaged in an “intellectual tug-of-war” with Baldwin’s ghost before realizing, “Yeah, I can’t talk to Baldwin. But he’s also not a black woman.”

One of the women Jenkins relied on was Joi McMillon, an editor who has worked with him since their days at FSU. (She earned an Oscar nomination for Moonlight.) She advocated keeping a scene in which Tish’s mother comforts her distressed, pregnant daughter. “To any other filmmaker, it would be a scene we could cut,” she says. “But when I told Barry this was a scene that women who watch this movie are going to need, he kept it in.”

Like Baldwin, whose protagonists are gay and straight, male and female, black and white, Jenkins has demonstrated that there is a responsible way to see beyond your own field of vision. “How much work are you willing to do to understand someone else’s experience?” he asks. “How far are you willing to go to allow others to help you fill in the gaps?”

The Hollywood in which Jenkins operates is drastically different from the one Medicine was released into a decade ago. “The audience has demanded stories that weren’t being told that they were hungry for,” he says. “But the test is going to be, five years from now, will we be the status quo or will there be more balance?”

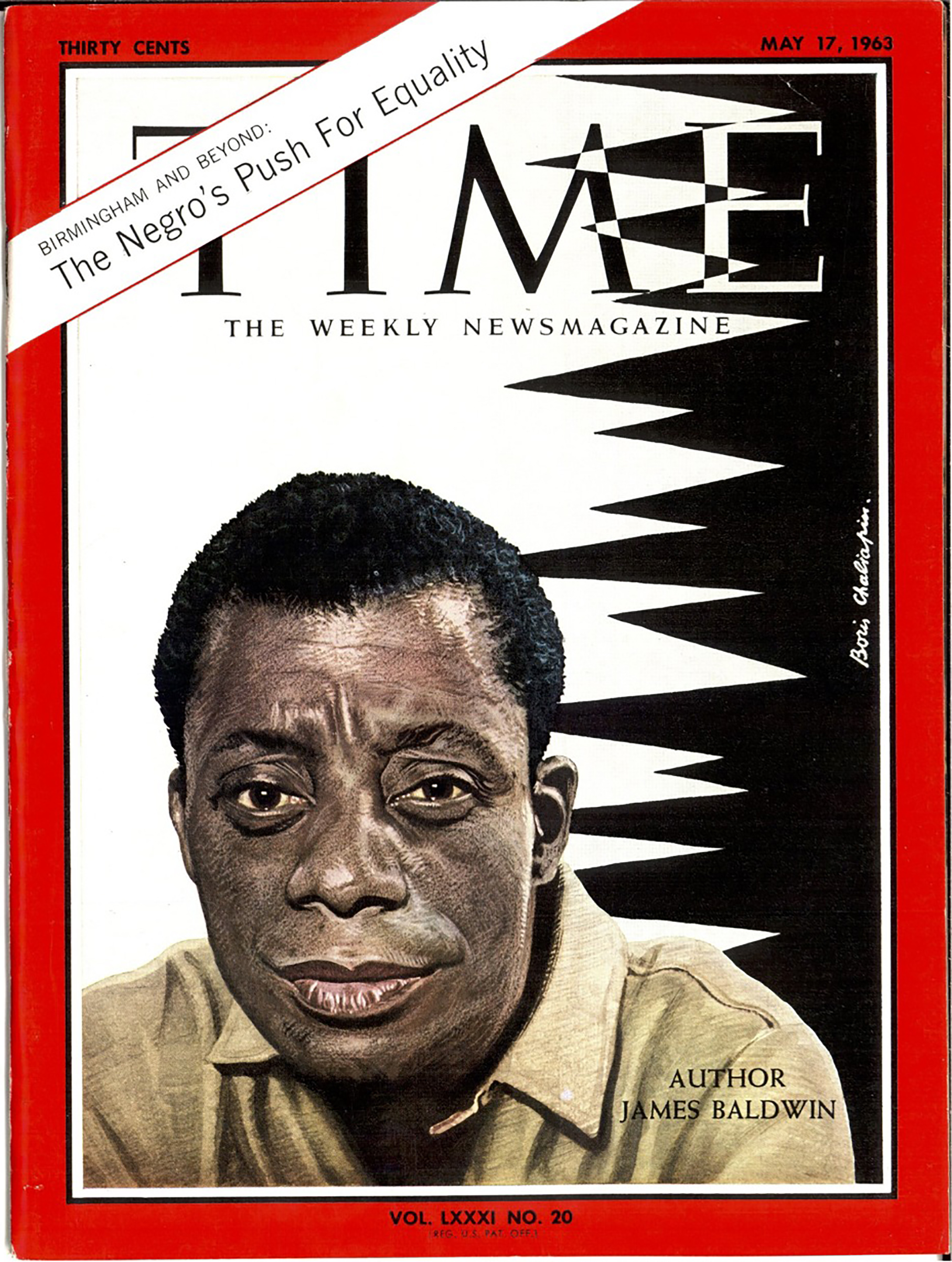

Either way, Jenkins will be part of the conversation. He’s currently at work on his first major TV project, an Amazon series based on Colson Whitehead’s Pulitzer Prize–winning Underground Railroad. But for now, he’s focused on Baldwin, whose words endure. When Baldwin appeared on the cover of this magazine in 1963, he addressed the possibility for change in the face of systemic inequality: “It is the responsibility of free men to trust and to celebrate what is constant–birth, struggle, and death are constant, and so is love–and to apprehend the nature of change, to be able and willing to change.”

Sometimes, it feels as if much has changed since then; sometimes, not so much. But as long as birth, struggle, death and love remain constant, Jenkins won’t run out of stories to tell.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Eliza Berman at eliza.berman@time.com