Building a protest movement during a pandemic requires creative — and virtual — work. For illustrators and artists with social platforms, their output has an attentive audience — and an influential role to play, in parallel to the George Floyd and Black Lives Matter protests sweeping the country. Floyd died in police custody in Minneapolis during an arrest on May 25 after Floyd gasped for air as an officer weighed down on him with a knee on his neck. The officer involved, Derek Chauvin, was since been fired and initially charged with third-degree murder and manslaughter. (Derek Chauvin now faces an upgraded second-degree murder charge.) As artists are aware, their responses can help build narratives of empathy and focus action on what matters.

The movement has seen large-scale marches and clashes with police in cities across the U.S. and abroad as late May turned to June, and has also grown online as support for anti-racism actions and systemic change against police brutality has become a dominant virtual conversation. While the act of re-sharing a portrait or re-tweeting a slogan has drawn criticism as potentially empty, the process of building solidarity through symbolism has played a core role in the history of protest, especially amid a pandemic that may rule out in-person activism for some. In the wake of Floyd’s death, social media sharing has helped to dissolve the distances between local pain and global outrage.

Creators have taken different approaches as they engage. For some, it’s a continuation of their activist spirit. For others, Floyd’s death marked a shift into newfound political involvement and more serious subjects. Millions of reposts later, however, one thing is certain: the conversation is still in its nascent stages. With that in mind, we asked artists about the creative process behind some of the most resonant original imagery of the moment. Much of the most popular works reimagine the subjects at hand, giving us new ways to grasp what’s going on.

Intentionally unfinished

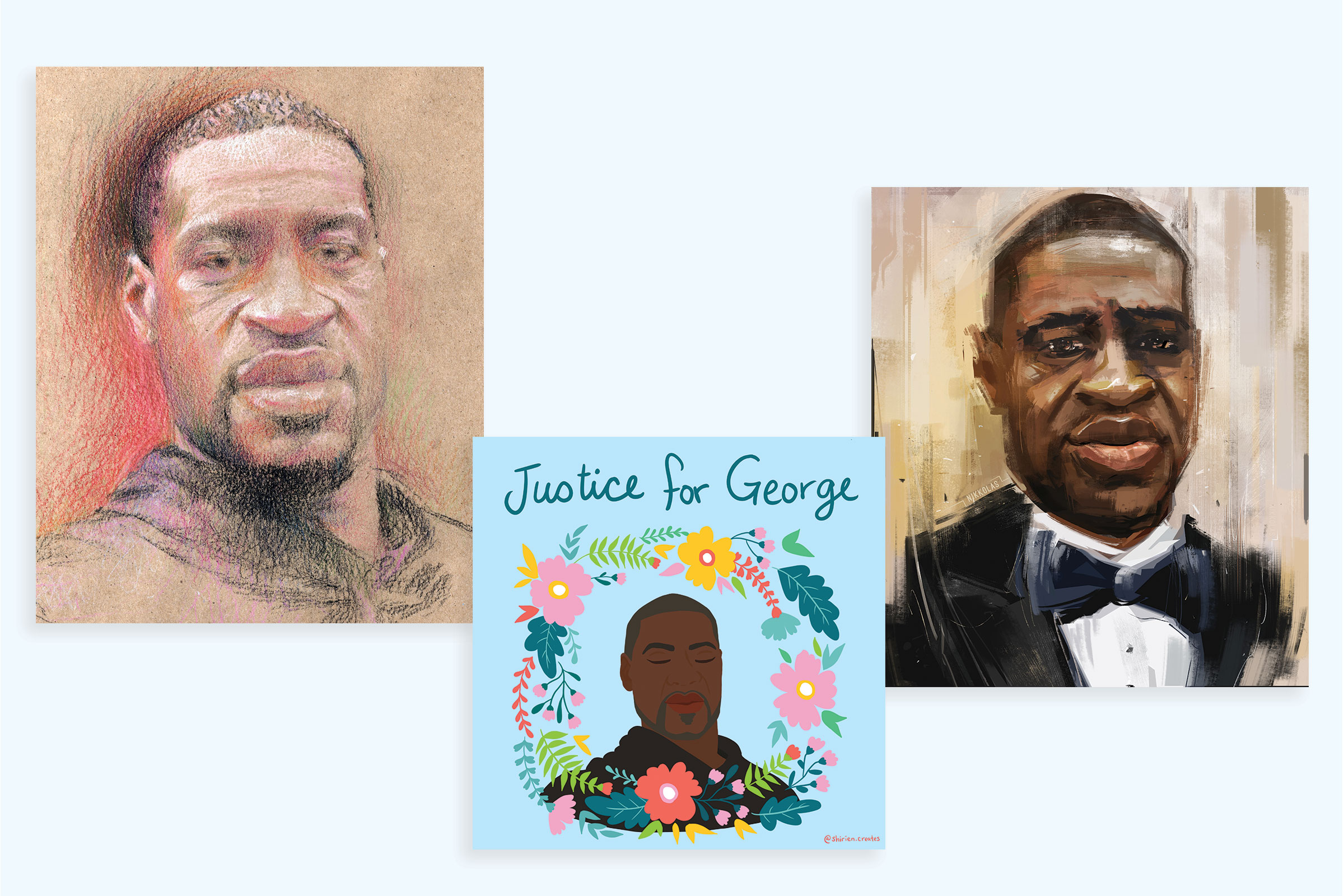

For Nikkolas Smith, an L.A.-based artist and activist who calls himself an “artivist,” there has never been a divide between the work he publishes and the justice-oriented goals of his creative endeavors. On May 29, he shared a digital painting commemorating George Floyd.

Like most of Smith’s portraits — many of which focus on other victims of police violence, like Ahmaud Arbery and Breonna Taylor — the style evokes a traditional oil painting, but is rendered almost as an abstraction. (He makes them in PhotoShop, and gives himself under three hours to complete them.) And the unfinished quality is intentional. Smith says it’s meant to echo the unfinished business of these lives, cut short. “I don’t like clean lines,” he tells TIME. “That’s a parallel to all these lives. They did not have a chance to see their end. They should still be living.”

Soon after posting his Floyd portrait, it was shared by Michelle Obama, among other celebrity fans. It was spread further by the official Black Lives Matter Instagram account, with whom he collaborated from the start. In fact, it soon became one of the widespread original images of the latest protest movement.

Smith coupled his image with a caption that calls for justice for Floyd, but recognizes that just the act of viewing and sharing is a powerful first step. “Even if there isn’t an action item, people are still seeing an image of a human being. The narrative is building up more and more that these are people who should be on this earth who are not here anymore, and their life is important,” Smith says. “To share it, even if it’s just that, is important. I’m hoping that all of this leads to a bigger, more substantial change, especially with accountability of law enforcement.”

Smith is no stranger to protest art. He was working as a Disney theme park designer in 2013 when he first captured attention for his illustration of Martin Luther King, Jr. dressed in a hoodie, meant to cast doubt on preconceptions of the differences between the civil rights leader and the young Trayvon Martin, the unarmed Florida teenager shot by George Zimmerman in 2012. Smith has been creating works with political and anti-racist themes ever since.

“A perfect poster child”

On the other hand, Illustrator Tori Press’s latest Instagram post was a departure for her. In 2016, Press checked out of her own freelance nine-to-five gig to focus on illustrating full-time, as an emotional response to the election that year. But she has always shared lightly humorous personal anecdotes with bits of advice about self-care and managing mental health in a signature style of pastel watercolors and black ink text — until now. “I’m not very political,” Press told TIME. “It’s not really something I wander into all that often. But in the wake of this murder, I’ve been sick all week. I couldn’t stay silent.”

The result: “If you want non-violent protests, listen to non-violent protestors,” reads her latest post in large black letters, with a small kneeling figure of former NFL quarterback and social justice activist Colin Kaepernick in the corner; it has over three times the likes of the prior post. “When something like this happens, and people are righteously angry, and justifiably so, but you hear folks being dismissive of the entire cause — I just think that’s a way to dismiss this fury, and the reason behind it,” she said. Press added that she feels particularly responsible to share this message as a white, privileged woman with a platform.

“I drew Colin Kaepernick because he’s a perfect poster child for someone who tried to make a peaceful protest, and was absolutely vilified for it. It’s just infuriating,” she said. “We need to have space to say, yeah, I recognize how furious you are.”

As she says in her caption, she feels there is a role for white people to play. “I can address my fellow white people and say look, this is a time we all need to stop and reflect. Really put yourself in the shoes of people who are angry right now, who are protesting. Have some empathy.” She hopes her illustration will help “at least a few people” to have that moment of self-reflection.

“It can turn into a tidal wave”

Eric Yahnker, a California-based satirist who has displayed his absurdist works in fine art galleries, laid aside his typical tongue-in-cheek tone when he published his latest Instagram post: another George Floyd portrait, done in colored pencils on a sheet of kraft paper as a “gut reaction” to Floyd’s death.

“I am absolutely unimportant in this story,” he said to TIME. He chose to draw Floyd as the “gentle giant” he was described as by friends, reflecting his “soft humanity.” “It absolutely guts me that if Mr. Floyd were a white gentle giant or anything other than black, he’d still be alive today,” Yahnker notes. “As a Jew, indoctrinated since birth to the scores of my own ancestry massacred by the hands of evil forces, I know full well that silence itself can be a painfully violent and oppressive act.” On its own, Yahnker knows a single piece of art can’t create real change. “But I am a firm believer in the power of the collective. If we all put a drop in the bucket, it can turn into a tidal wave,” he says.

Reimagining the possibilities

One of the most widely circulated images is an illustration from Shirien Damra. It’s a pastel, color-blocked portrait of Floyd that sees him wreathed in flowers, one in a series of similar portraits Damra has done for people who have recently fallen victim to violence. Damra, a former community organizer in Chicago and a Palestinian-American, turned to this form of commemoration in order to spread awareness in a way that avoided sharing videos that she said can be “traumatic and triggering,” she told TIME. “I think art can touch our emotional core in a way that the news can’t.” Damra adds that one thing artists can do is help illustrate what comes next.

“We know what we don’t want. We don’t want any more black lives targeted by police and white supremacy. But one thing that I have found we struggle with is actually imagining what kind of things we do want to see in our world,” she says. “I feel like as artists, one role we could play is allowing ourselves and others to reimagine the possibilities. Our society will likely never turn back to how it used to be before the pandemic and everything happening right now. Art can be a powerful catalyst in bringing more people together to take action.”

Damra’s Instagram account is only a year old. But especially in the pandemic era, people are turning to the digital sphere to consume art perhaps more than ever, by default. “This has opened up a way to reach more marginalized communities who need art most during this heavy time,” she says.

Inspiring protest signs

Another popular image is a gesture to the Black Lives Matter movement by the French artist duo Célia Amroune and Aline Kpade, who go by the name Sacrée Frangine. Like a spin on an earth-toned Matisse cut-out, their trio of Black faces — overwritten with the “Black lives matter” slogan — is a universal statement that is just abstract enough to be repurposed in many ways; protesters have even drawn versions of it for signs at marches. Amroune and Kpade may not be U.S. citizens, but they told TIME they feel “very close to” the movement. This has, after all, had a wide reach. The comments to their art are a chorus of “thank-yous” and heart emojis, with the promise of sharing.

As social media was overtaken by “blackout” trends on June 2, these works momentarily disappeared from feeds. But they will resurface again.

“Some people who never spoke out before — when Mike Brown or anybody else was killed — they saw this video, they see this art, and say, now I’m going to say something,” Smith said about what’s different this time around. “I don’t even really know where things are gonna go from here, but it’s getting to a boiling point. People are done. They’re going to make their voices heard.”

As for Smith, his latest piece of art, called “Reflect,” isn’t a portrait but a depiction of a single masked protester, kneeling at the foot of a line of riot-gear-clad policemen and raising a mirror to their hidden faces. “Can we just hold up a mirror to what this looks like right now?” Smith wants to know. That’s what contemporary art is for, after all: to refract back reality, and raise questions about what we are willing to accept.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Raisa Bruner at raisa.bruner@time.com