![George Grosz [Misc.];George Grosz;Adolf Hitler [Misc.] George Grosz; Adolf Hitler](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/grosz.jpg?quality=85&w=2400)

When Adolf Hitler took charge of Germany 85 years ago this summer, he did not, contrary to popular belief, “seize power.” Rather, Germans elected him their Führer, or leader, in a referendum on Aug. 19, 1934 and subsequently chose to subscribe to the cultural narrative that he created: that Germany had become too open, too tolerant of cultural diversity in the early 20th century. This openness, Hitler argued, had caused their recent national identity crisis.

Hitler knew that to conquer the wounded hearts of a broken citizenry, he must first conquer culture itself. Dozens of artists faced his persecution when he pushed “Degenerate Art” out of museums and into a derisive exhibition in 1937, but very few tried to warn against it through their work.

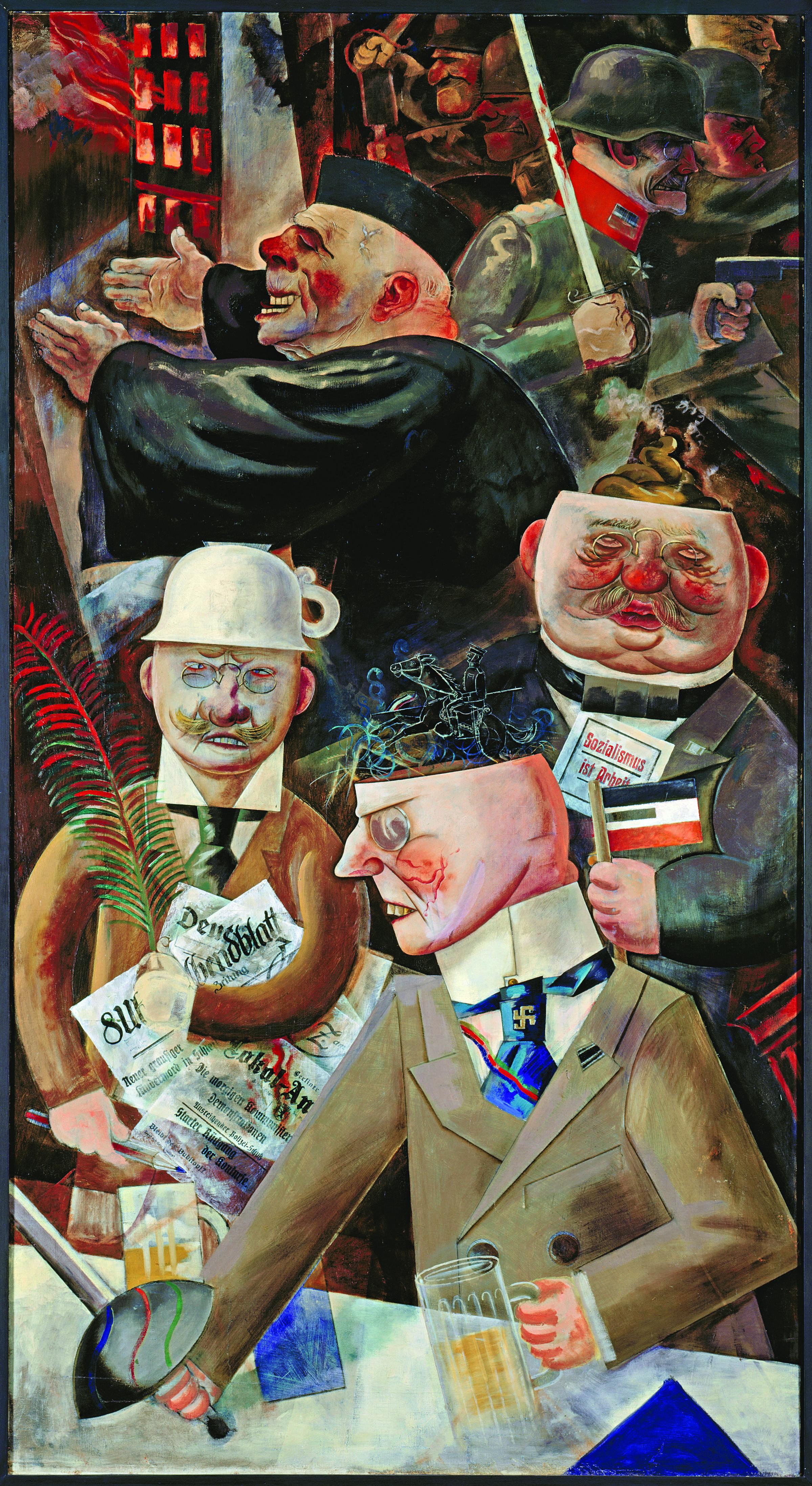

One notable exception was George Grosz, a spirited rabble-rouser who risked his career, family, physical safety and mental health to sound the alarm as early as 1923, parodying Hitler’s view of aggressive nationalism in “Hitler the Savior,” a work that mocks Hitler as a Teutonic warrior in a one-shoulder tunic. In his 1926 painting “Pillars of Society,” the then-33-year-old artist warned his fellow Germans that, if petty government sniping and extremist Christianity were not nipped in the bud, Hitler’s rise would be the likely consequence. Grosz further warned against radical far-right religious views in 1927’s “Shut Up and Do Your Duty,” a work that shows Jesus Christ nailed to the cross wearing combat boots and a gas mask—a criticism of politicizing Christianity that drew praise from pacifist Quakers in the United States.

Yet most Germans dismissed Grosz’s anti-Nazi work as hyperbolic and offensive to Christianity, a feeling that far-right activists exploited to distract from what he was saying. Then the death threats began. One night in the early 1930s, Grosz discovered an iron pipe at his front door with a note attached. “This is for you, you old Jew-Pig, if you keep going with what you’re doing.” The artist knew that the reality that he was not Jewish would make scant difference to violent extremists.

After it became clear that the Nazis would be victorious after Hitler was sworn into power in January of 1933, with elections called for two months later, Grosz and his wife Eva fled as persecuted activists to New York, with their two sons, sailing separately to avoid suspicion. He worked tirelessly to integrate and successfully learned both English and the culture of his new country. Yet Grosz still struggled to convince Americans that Hitler’s cultural clampdown was an obvious precursor to stamping out civil rights first for women, minorities and the press—before finally eradicating them for all Germans.

In his 1934 work “Peace,” Grosz foretold that powerful countries would appease Hitler, leading to a Second World War. In the striking black-and-white piece, three cars race down a road, bearing the flags of Imperial Japan, Italy and the Second Spanish Republic. Egging them on is a car brazened with a Swastika.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

Grosz created the work a full two years before the Spanish Civil War, three years before the Second Sino-Japanese War, and five years before World War II. It seemed too preposterous to be prophetic, and American culture critics dismissed the piece.

By the time Americans realized Grosz had been right, it was too late.

Decades later, in the spring of 1959, Grosz and his wife Eva moved back to Germany. Eva had been perpetually homesick, and Grosz was seeking emotional closure after years of exhibiting clear signs of trauma. Yet reentry in Berlin was difficult: Grosz had access to even fewer mental health resources than in the U.S.; the art world was in shambles, many of his friends were dead and political chaos continued in Germany with the looming Cold War. Then, on July 6, 1959, after a night out with friends, the inebriated artist slipped on the stairs of his apartment, dying in the hallway from the injuries. With him died his failed dream of warning the world of dictatorship.

So why is Grosz’s heroic story not better known?

In Germany, the reasons are twofold. For most Germans, lauding the risks that Grosz took also involves acknowledging that others—perhaps their parents, grandparents or great-grandparents—enabled Hitler’s rise by not speaking out as the artist did. Secondly, while Grosz was able to escape with some documents that facilitate research, the Nazis destroyed copious works and documents left in Berlin.

Americans, on the other hand, have an uneasy, centuries-old relationship with failure. Millions grew up with the fairytale that if an individual is fighting for what is right, that individual will certainly win and be rewarded for it.

Yet it is critical that we heed Grosz’s warning in our own time: the dismantling of civil rights is portended by the dismantling of culture. It is critical that members of a society recognize that there are times when risking our careers, and even our safety, may be necessary to protect that society’s future.

When others take those risks, the rest of us should pay attention.

Mary M. Lane is the author of Hitler’s Last Hostages: Looted Art and the Soul of the Third Reich, available now from PublicAffairs.

Correction, Sept. 18

The original version of this article misstated the timing of German elections in 1933. They were called in January but held in March, not in January.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com