On a recent evening, out of a combination of professional obligation and morbid curiosity, I sat down on my couch and turned on my TV to watch celebrities … sit on their own couches to watch TV. That is literally all that happens on Celebrity Watch Party, which now occupies a full hour of Fox’s Thursday lineup. Famous faces including the Osbournes, Tyra Banks and Rob Lowe stare into their screens—and out at viewers who get to observe them cooing over, say, an elephant doc narrated by Meghan Markle. Just like us!

As reality TV goes, Watch Party is gentle enough. It doesn’t traffic in public humiliation like Love Is Blind or inspire virulent misanthropy like Summer House. Yet it manages to offend through sheer dullness. The highlight of the premiere comes when a listless Ozzy observes the unmasking of pop-classical phenom Jackie Evancho on The Masked Singer and slurs, “Who the f-ck was that?” Shot remotely and infused with the half-glib, half-naive “We’re all in this together, never mind that I’m quarantining in a mansion with live-in staff” spirit that has pervaded celebrity-driven entertainment since March, Watch Party may be TV’s most pathetic response yet to the COVID-19 crisis.

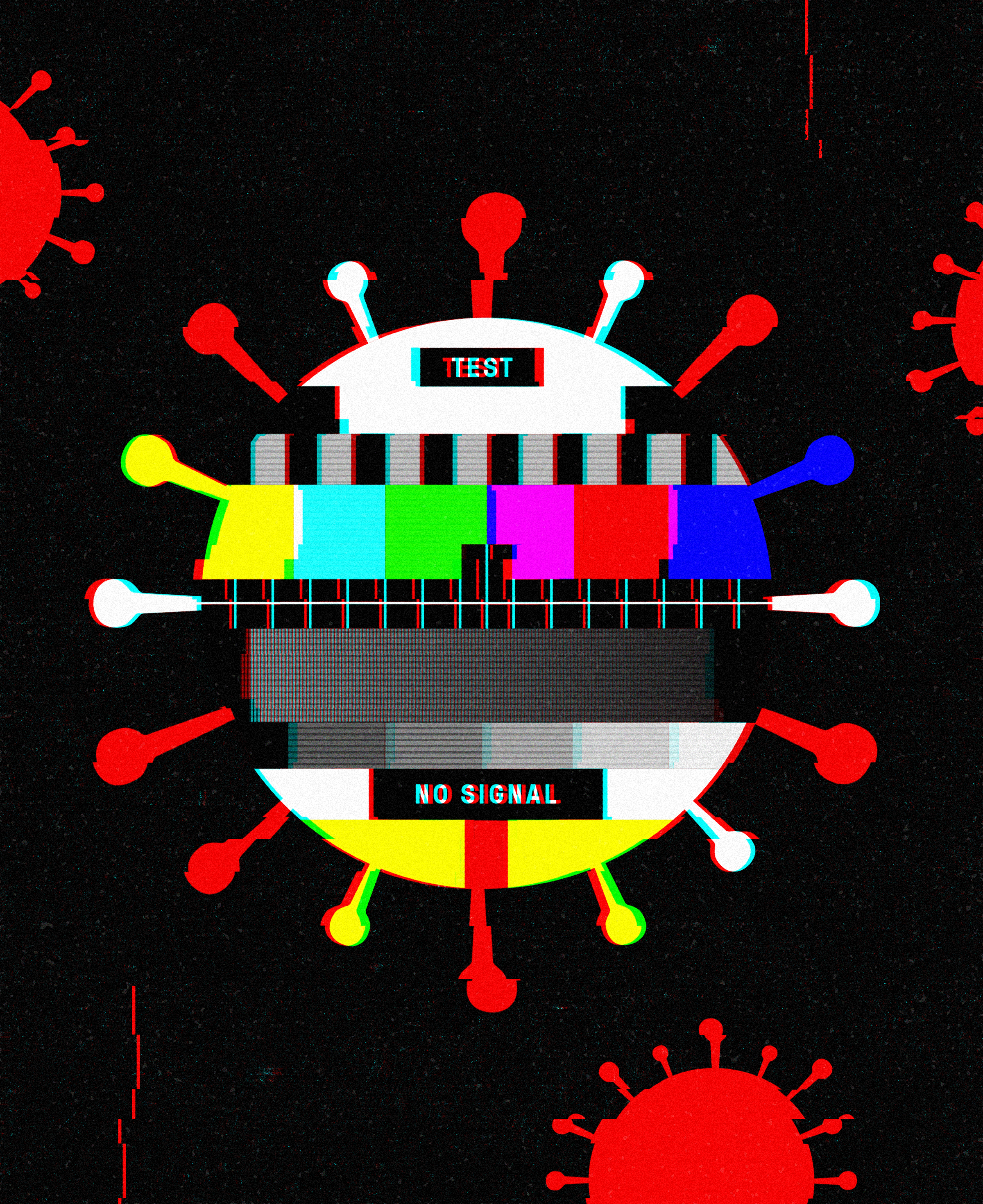

After years of audience attrition, linear television was thrust into chaos when social-distancing measures halted production on most shows. Suddenly, not only scripted series but also the sports, talk shows and reality programming that have kept broadcast and cable channels in business amid the streaming revolution were canceled. While streaming services have profited from a nation stuck at home, many traditional networks are absorbing yet another ratings blow. The future of real-time TV has looked bleak for quite some time. But, for a long list of reasons, coronavirus appears to be accelerating the decline.

Although the Big Five broadcast networks (ABC, CBS, NBC, Fox and the CW) have been bleeding viewers since cable got serious about scripted originals in the 2000s, it’s only in the past few years that the long-term future of television has started to click into place. Even as the volume of new content keeps increasing, the field of competitors is contracting. And as media ownership has consolidated—with Disney buying 21st Century Fox, while Discovery swallowed Food Network, HGTV and more in a Scripps acquisition—each conglomerate is amassing the catalog and intellectual property to support a stand-alone streaming platform.

Hence the second wave of subscription services that arrived in November with Apple TV+ and Disney+, the latter of which is coasting on its Marvel, Star Wars and family-friendly animated library. In April, the service reached 50 million paid users, having added more than 21 million in the previous two months alone. While COVID-19 likely played some role in the spike, Disney+ did launch across Europe and in India during that period. Stateside viewers also have the option of bundling it with ESPN+ and Hulu, which caters to adults, for a package comparable in price with Netflix.

Not that Netflix seems hurt by the competition. Streaming has benefited from our quarantine-induced boredom. The New York Times reported that the number of American households with at least one streaming subscription jumped by 2.5 million, to 74%, in the first quarter of 2020. Netflix gained nearly 16 million subscribers during the same period—a new record. The company warned shareholders that the rapid growth would probably end with the stay-at-home orders. Still, it’s notable that the sign-ups came despite Netflix losing some of its most popular licensed titles. (Friends left in December.) Years of content churn have given the service independence; now it can attract subscribers on the strength of a library it actually owns.

That library should also discourage defection to new and upcoming subscription sites from media super-powers that are pulling their titles from Netflix. On May 27, WarnerMedia will debut HBO Max, with a handful of day-one originals alongside old and new series from HBO, Turner and Warner Bros. (among them: Friends); movies will range from Casablanca to DC Comics superhero blockbusters. Peacock, from NBCUniversal, launches July 15. Headlining its similar mix are streaming staples Parks and Recreation, 30 Rock and, when it leaves Netflix in 2021, The Office.

This was always going to be a big year for the “streaming wars,” implicit in which was the gradual exodus from traditional TV. But quarantine has stoked viewers’ hunger for content and hastened their adoption of non-linear platforms. Shaped by the rhythms of weekdays and weekends, school and work outside the home—routines that no longer exist for many of us—real-time TV schedules suddenly seem absurd. In the time of coronavirus, the only way to watch is to binge.

Braced though they might’ve been for a bumpy year, broadcast and cable could never have anticipated what’s befallen them since March. Live and quick-turnaround programming was the first crisis. Talk shows shut down. Reality shows that aired live episodes, like American Idol, were also out of luck. Basketball, baseball and hockey had their seasons delayed indefinitely or cut short; the Olympics were postponed.

Not all of linear TV’s attempts to adapt have been as feeble as Celebrity Watch Party—a ratings flop as well as a creative one. Idol, Saturday Night Live and many talk shows, from The View to Showtime’s Desus & Mero, have returned as lo-fi video chats. Live-action series like NBC’s The Blacklist and Pop’s One Day at a Time are turning to animation. And a raft of socially distant all-star events—a Parks and Rec reunion on NBC, a pair of Disney sing-alongs on ABC—have seen networks playing their (or their corporate parents’) hits, to relatively large audiences. News shows are, for obvious reasons, more vital than ever.

But more problems lie ahead. COVID-related production delays have already postponed premieres, like the fourth season of FX’s Fargo. As the pandemic persists, broadcasters have had to slash new series orders. Fox recently unveiled a fall schedule heavy on reality and animation, with L.A.’s Finest-—a middling police procedural imported from cable provider Spectrum—filling out its scripted lineup.

Streamers have also halted production, of course, but their release models build in more wiggle room. They don’t rely on ad sales, premiere weeks or the jigsaw puzzle that is prime-time scheduling. Besides, Netflix content boss Ted Sarandos announced in April’s quarterly earnings call that not only is shooting completed on most of this year’s shows, but “we’re actually pretty deep into our 2021 slate.”

As much of a headache as this all must be for network execs, it isn’t necessarily bad for the corporations behind them. Peacock parent NBCUniversal’s holdings include NBC and its cable-news offshoots, along with cable channels including USA, Telemundo and Bravo. Warner has HBO, Cinemax, CNN, TBS, TNT and more—plus content from the CW, jointly owned with -ViacomCBS. Viacom has been among the slowest to get its streaming strategy in order, relying on à la carte offerings; now the company is scrambling to consolidate its catalog. Even Fox, which retained its broadcast and news channels in the Disney deal, acquired ad-supported streaming platform Tubi in April, indicating an investment in the technology.

Smaller cable businesses have seen mixed results in the past few months. The relatively highbrow AMC Networks (BBC America, IFC) predicted a steep revenue drop this quarter, but comfort-TV purveyor Discovery Communications is flourishing. In the long run, it’s cable and satellite services that seem doomed to lose. Dish Network and Comcast reportedly each lost more than 400,000 subscribers in the year’s first quarter; AT&T was down more than a million. Yet even that news is deceptive: Comcast owns NBCUniversal, and AT&T owns WarnerMedia.

The deeper we get into the streaming wars, the clearer it becomes that a few megacorps are destined to control the future of TV—the same ones that have shaped its past and present, for the most part. This holds true whether we’re talking about Netflix vs. Disney or paid vs. ad-supported models or broadcast vs. cable vs. streaming. Those that stand to suffer most from this shift are TV’s most vulnerable producers and consumers: smaller creators and distributors that don’t have the budgets to compete with multi-nationals, older viewers who may not be adept with technology, families that rely on broadcast because they can’t afford pay TV.

In fact, shows like Celebrity Watch Party exist on network TV neither solely because of quarantine nor because the corporations behind them are broke or uninspired. They exist because the money, and the companies’ attention, is somewhere else.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com