One of the worst symptoms of any plague is uncertainty—who it will strike, when it will end, why it began. Merely understanding a pandemic does not stop it, but an informed public can help curb its impact and slow its spread. It can also provide a certain ease of mind in a decidedly uneasy time. Here are some of the most frequently asked questions about the COVID-19 pandemic from TIME’s readers, along with the best and most current answers science can provide.

A note about our sourcing: While there are many, many studies underway investigating COVID-19 and SARS-CoV-19, the novel coronavirus that causes the illness, it is still essentially brand new to science. As a result, while we’ve drawn primarily on peer-reviewed studies published in scientific journals, we have cited some yet-to-be-published research into important aspects of COVID-19 when appropriate.

Coronavirus FAQ

What are the symptoms of COVID-19?

Who’s most at risk for COVID-19?

Are children at risk?

How long does COVID-19 last?

How long is COVID-19 infectious in people?

Can I get COVID-19 and the seasonal flu or common cold at the same time?

What’s the treatment for COVID-19?

How does a COVID-19 test work?

Should I get tested?

How does COVID-19 spread?

Is COVID-19 airborne?

Is there any difference between being indoors or outdoors when it comes to transmission?

Do masks work for preventing the spread of COVID-19?

How long does the COVID-19 virus survive on surfaces?

Is there any risk of the COVID-19 virus living on mail & packages?

Is there any risk with food delivery services?

Does rain wash away the COVID-19 virus?

What should I do to shop safely?

Should I worry about my clothes after I’ve been outside?

Can I get COVID-19 more than once?

If I get COVID-19 and recover, am I immune and safe to be around/help out older family and neighbors?

I’ve been social distancing for two weeks. When is it safe for me to go see family?

Can my dog or cat get COVID-19?

Can the COVID-19 virus live on my pet’s fur?

Do flies, mosquitoes, or other insects carry or transmit the virus?

Can cleaning products kill the COVID-19 virus?

Does it matter what type of soap I use to wash my hands?

What are the practices for doing laundry in a shared/public laundry room?

What are the symptoms of COVID-19?

Studies have shown that while some COVID-19 patients get only very mild symptoms or none at all, some can develop severe pneumonia and other health issues. A World Health Organization report from February found that around 80% of patients with laboratory confirmed cases “have mild disease and recover.” Researchers are not certain how many people infected with the virus are nearly or entirely asymptomatic. “There is not a single reliable study to determine the number of [asymptomatic sufferers],” says a metastudy conducted by scientists from Oxford University, and published online on April 6. “It is likely we will only learn the true extent once population-based antibody testing is undertaken,” write the study authors. (The metastudy, which looked at 21 earlier studies from around the world, has not been peer-reviewed.) The only way to know for sure if you are infected with SARS-CoV-19, the virus that causes COVID-19, is to get tested.

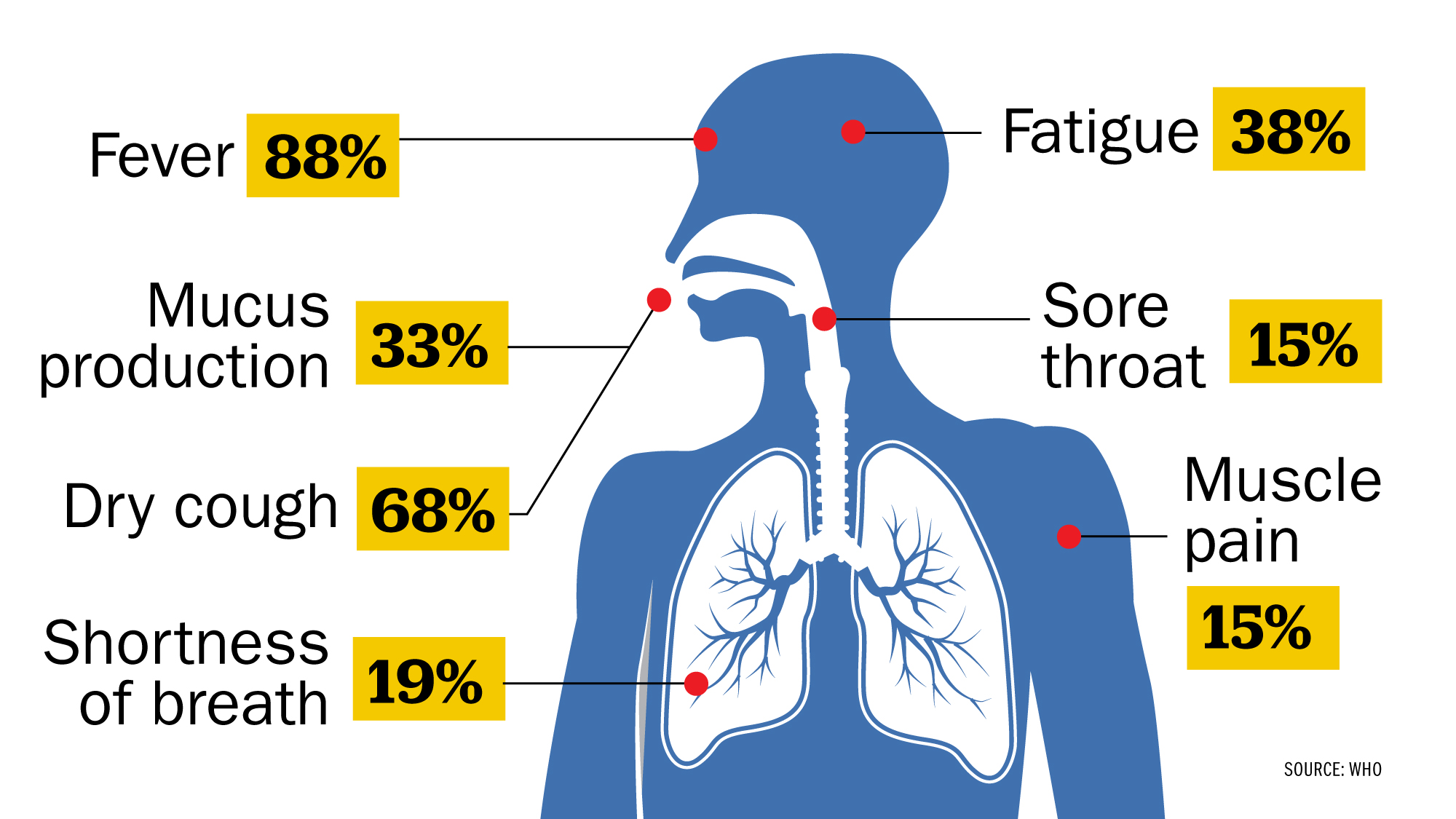

According to a study of nearly 56,000 laboratory confirmed cases cited in the WHO report, the most common symptom, experienced by 88% of confirmed patients, is a fever. The other most common symptoms according to that study are, in descending order:

One thing missing from this list is anosmia, or loss of sense of smell. Anecdotal reports suggest that people with milder cases of the disease could have telltale symptoms like the loss of their sense of smell and/or taste, however the WHO has not yet added those symptoms to its official list, as the data are not yet strong enough. But an analysis of a COVID-19 symptom-tracking app in the U.K. shows 59% of the 579 users who had tested positive for the disease reported a loss of smell and taste, compared to 18% who did not have the disease. And in April, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention updated its list of possible symptoms of COVID-19 to include “new loss of taste or smell” among them. —Billy Perrigo

Who’s most at risk for COVID-19?

At this point, it seems people of all ages are susceptible to infection of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. However, those most at risk of severe cases of the illness are the elderly and people with underlying health conditions (like high blood pressure, heart disease, lung disease, cancer and diabetes) according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) clarifies further, stating that those most at risk for severe illness are:

A study published in JAMA Network on April 22 looked at 5,700 patients in the New York City area who had been hospitalized for COVID-19, and found that over 94% had at least one underlying health problem. The most common were hypertension, obesity, diabetes, heart disease, and asthma:

In the U.S., 80% of COVID-19 related deaths have been adults 65 years and older, according to the CDC.

It is too early to tell if pregnant women are also at risk of severe illness caused by the coronavirus, according to the WHO. Some newborn babies have reportedly tested positive for the virus, but it is unclear how the transmission occurred.—Jasmine Aguilera

Are children at risk?

Yes, but the good news is that their risk may be lower than that of most adults. Chinese doctors first reported that children did not seem to be getting infected as easily as adults, and that they also did not need to be hospitalized as frequently as adults did. That trend seems to be holding true in the U.S. as well. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that compared to adults, children under the age of 18 are less likely to experience the typical symptoms of infection, including fever, cough and difficulty breathing, and are also less likely to need hospitalization and less likely to die of COVID-19.

That’s unusual for a respiratory disease, since viruses like influenza often strike the very young and the very old more aggressively, given their more vulnerable immune systems. “I can’t think of another situation in which a respiratory infection only affects adults so severely,” says Dr. Yvonne Maldonado, professor of pediatrics at Stanford University School of Medicine and chair of the committee on infectious diseases at the American Academy of Pediatrics. “This is not common at all; we just don’t know what is going on here.”

One theory is that the severest symptoms of COVID-19 in adults may be caused by an overactive immune response to the virus in the lungs, which can make breathing difficult. Children’s immune systems may not be developed enough to launch such an aggressive reaction, and that may spare them some of the infection’s worst consequences.

The data suggest that infants may be more likely to need hospitalization if they are infected compared to toddlers, but more studies are needed to better understand how the virus is affecting children overall. In the meantime, doctors recommend that parents consider children as vulnerable to infection as adults, and appreciate that young ones can spread the virus as effectively as adults too, even if they don’t have symptoms.—Alice Park

How long does COVID-19 last?

That depends on the severity of infection. If it’s a mild infection, like most people get, symptoms will likely last for about seven to 10 days and will be similar to those caused by the seasonal flu, says Dr. Emily Landon, the chief infectious disease epidemiologist at the University of Chicago Medicine. But for roughly 20% of COVID-19 patients, infection can worsen after this initial period, and in some cases lead to hospitalization. For even people with moderate cases, symptoms can last for a month or more until they are fully recovered.

“You can have people who have very mild symptoms that last a couple of days and then you have other people who can really get quite sick and go to the intensive care unit and be there for a month or more,” says Dr. Albert Ko, department chair and professor of epidemiology at the Yale School of Public Health. Those who get so severely ill that they are battling pneumonia and potential respiratory failure in intensive care units could take over a month to recover, Ko says.

Mild symptoms are unlikely to last longer than three weeks. “The fatigue can linger, as can the loss of appetite and some people routinely have a nagging cough after a viral infection that can last for weeks,” Landon says. “So some people will have lengthy symptoms but those aren’t really from active viral infection. They are more of a recovery syndrome.”—Sanya Mansoor

How long is COVID-19 infectious in people?

It’s unclear. We do know that people infected with the virus that causes COVID-19 can be “contagious a few days before they even show symptoms and some people never really have much in the way of symptoms but can definitely pass on the virus,” says Dr. Emily Landon, the chief infectious disease epidemiologist at the University of Chicago Medicine. “What we don’t know is how long they remain contagious.”

The general rule Landon and her colleagues use is that “you’re probably good” if a week has passed from when you first began feeling sick and you’ve had three full days of feeling completely well. That means no more cough and no more fever for at least three days. “You are probably contagious starting two to three days before you develop symptoms and until your fever is gone and your cough is pretty much resolved,” Landon says.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) says more or less the same in its guidelines, but is more explicit, telling COVID-19 patients that they are free to break quarantine only if:

(The full CDC guidelines are here.)

The World Health Organization offers similar guidance to the CDC, recommending that COVID-19 patients be released from the hospital, isolation or home care only after they have two negative tests at least 24 hours apart and have clinically recovered. If testing is not an option, the WHO advises keeping individuals isolated for another two weeks after the symptoms are gone because they may continue to “shed”(or emit from the body) the virus.—Sanya Mansoor

Can I get COVID-19 and the seasonal flu or common cold at the same time?

Yes.

Flu and COVID-19 are caused by two different viruses and there is nothing preventing you from getting exposed, and infected with both at the same time. It’s unusual, but possible.—Alice Park

What’s the treatment for COVID-19?

For those with mild cases of COVID-19, the key is to get plenty of rest and liquids, as well as to take vitamins and eat a healthy diet, says Dr. Emily Landon, the chief infectious disease epidemiologist at the University of Chicago Medicine.

For severe cases, “there’s no evidence, based on the typical scientific rigor that we demand, for any specific treatment at this point,” says Dr. Albert Ko, department chair and professor of epidemiology at the Yale School of Public Health.

But there are trials underway testing some promising therapeutic options. One has been in the headlines recently: hydroxychloroquine. President Trump has repeatedly touted the drug (currently used primarily to treat malaria and some autoimmune diseases) as part of a possible cure for coronavirus even though experts, including Ko, say there is not enough evidence to currently recommend the treatment. “I have several concerns about the design of those trials,” Ko says, adding that while we know that hydroxychloroquine “suppresses viral growth in the test tube,” we “don’t know exactly why and if it’s going to work in people.” Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and member of the White House Coronavirus Task Force, has said the research that produced the data so far “was not done in a controlled clinical trial. So you really can’t make any definitive statement about it.”

Another promising option is remdesivir, an injectable drug developed to fight ebola. “[Remdesivir] is probably the most promising of the drugs that we have available,” says Dr. Emily Landon, the chief infectious disease epidemiologist at the University of Chicago Medicine, but the full scope of its effects won’t be known until further analysis is conducted. Trials for remdesivir are currently underway, and early reports suggest the drug may effectively help COVID-19 patients get better, faster.

Repurposed drugs like remdesivir and hydroxychloroquine can skip several regulatory steps and go straight to late-stage trials assessing effectiveness whereas new drugs have to face many more regulatory hurdles. (Hydroxychloroquine has already been approved for a number of medical purposes, while remdesivir, though tested as an Ebola treatment, has not yet been approved for anything.) An Emergency Use Authorization issued by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration can speed up the process for newer drugs, though even then, approval typically takes at least six months.—Sanya Mansoor

For more on treatments:

How does a COVID-19 test work?

The current gold standard is a PCR (polymerase chain reaction) test, which detects the existence of the genetic material of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, in a person’s body. The test requires a sample of cells from the back of the nose and throat, and then uses chemical probes targeted to find the genes that code for the biggest feature of the virus, its spike proteins, which dot the surface the virus like a crown (hence the name “coronavirus”—corona is latin for crown). The Food and Drug Administration has also granted emergency use clearance for tests that can pick up the virus’ genetic signature from saliva. Some need to be done at a doctor’s office or medical facility, while others can be done at home and people can send the spit samples into a lab.

If someone is infected with SARS-CoV-2 and has traces of virus, these types of PCR tests will pick it up. It’s generally pretty sensitive, meaning it can pick up even relatively low levels of the virus.

But it has one key drawback: it may not find the virus if someone is tested very early after infection and there isn’t enough virus yet for the probe to spot.

The other type of test currently in use is a blood-based test that looks for antibodies to the virus. Antibodies are made by the body’s immune system to fight viral infection, so picking up antibodies is an indirect way of knowing that virus is present. This test also has drawbacks: it isn’t able to accurately identify people who are infected but haven’t yet generated enough antibodies for the test to detect.—Alice Park

Should I get tested?

That depends on a number of different things. First, if you have a fever, cough and shortness of breath, you might consider getting tested since these are the hallmark symptoms of COVID-19.

If you aren’t sick, you still might need a test if you are at high risk of being infected. That category of people includes health care workers and anyone living with or caring for someone who is infected. Your exposure means you have a higher chance of getting the disease. Getting tested and knowing if you are positive means you can self-isolate and take other precautions in order to prevent spreading the virus to others.

Remember, however, that while you can ask for a COVID-19 test, you still need a doctor to authorize it. Even at-home test kits require you to connect with and answer questions with a telehealth doctor first, who will decide if you need the test.

At this point in time, due to limited availability of tests, the focus is on using testing to identify who is positive and in need of urgent medical care. It’s also important for knowing who is positive and therefore can spread the virus to others. As cases start to subside, the latter group will become more important as public health experts turn to testing as a way to control new infections. Testing will tell them who can return to work once shelter-in-place orders are lifted, and who, if they are positive, still need to self-isolate at home.—Alice Park

For more on testing:

How does COVID-19 spread?

The prevailing means of transmission is via virus-containing microdroplets expelled when someone who is infected either sneezes or coughs. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, genetic material of SARS-CoV-2, the virus responsible for COVID-19, has been found in fluids in both the upper and lower respiratory tract, meaning that the saliva and mucus of an infected person is likely to contain the virus.

Less is known about other body fluids and products. One recent study from Sun-Yat Sen University in China found that genetic material from the virus is present in fecal samples from infected individuals. The CDC agrees that fecal transmission is possible and also reports that infectious SARS-CoV-2 has been found in blood. Even less is known about other bodily fluids, including urine, vomit, breast milk and semen. But CDC guidance for people who are sick and not hospitalized is nonetheless to “clean and disinfect all surfaces that may have blood, stool or other body fluids on them.”—Jeffrey Kluger

Is COVID-19 airborne?

The virus that causes COVID-19 is an airborne pathogen, and humans are its primary delivery vehicle. Coughing, sneezing and even just speaking release droplets on the order of 100 microns in size (or 1/100th of a centimeter) into the air. “Your larynx is vibrating as you speak and it acts as a little nebulizer,” says Dr. Christopher Gill, associate professor of global disease at the Boston University School of Public Health. (A nebulizer turns a liquid into a mist.)

The half-life of the aerosol droplets is about an hour, according to Gill, which is short, but still leaves plenty of time after which the fluids released by an infected person’s cough or sneeze are infectious. It’s unclear to scientists if a viral particle continues to be infectious when the micro-droplet that contains it evaporates.

Even in a time of social distancing, enclosed public spaces like grocery stores remain problematic, Gill says, since a great many people may pass through an infected space within the hours the virus lingers in the air. “You should worry more about the air you breathe in a grocery store than about whether someone touched the broccoli,” he says.—Jeffrey Kluger

Is there any difference between being indoors or outdoors when it comes to transmission?

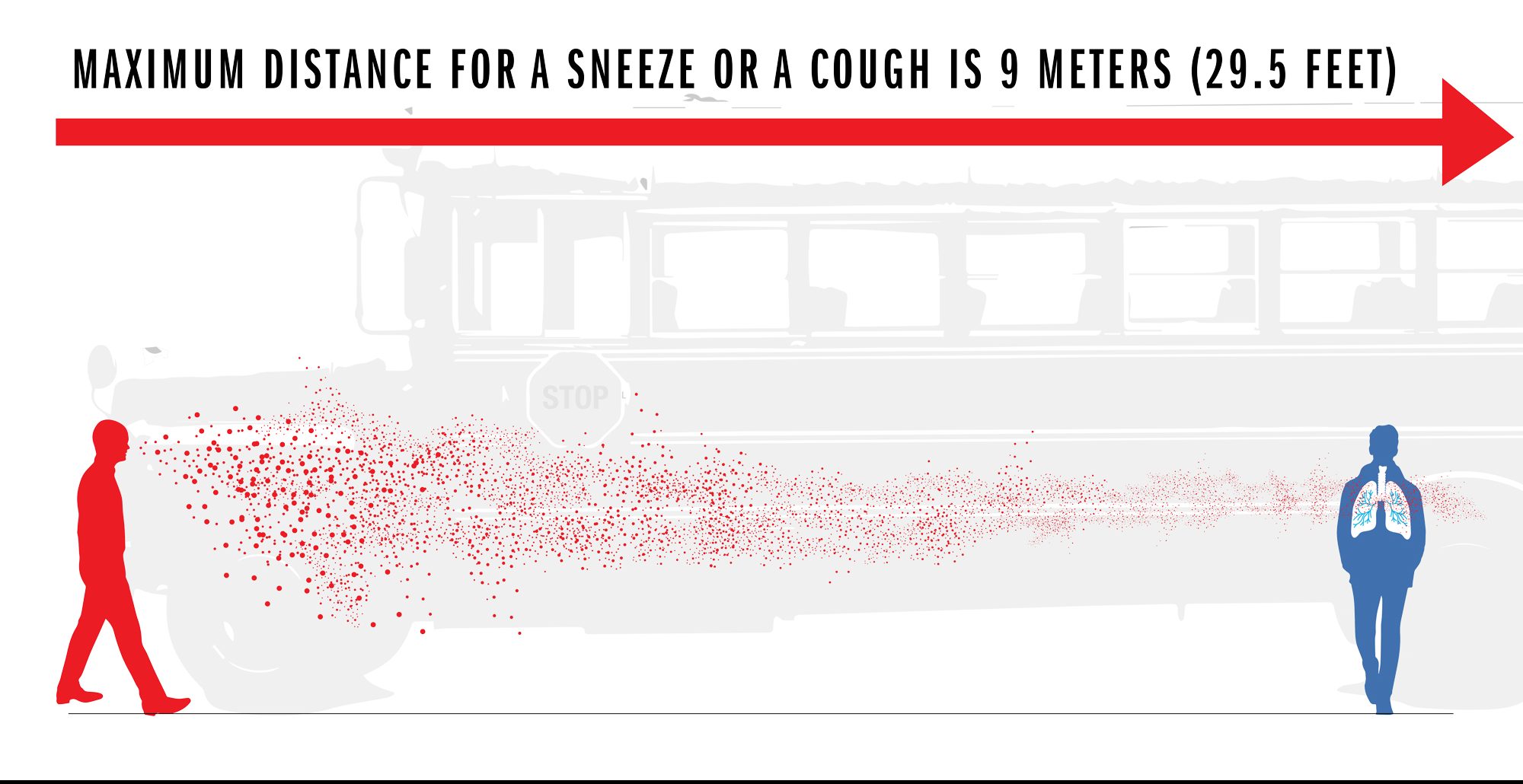

Staying home and social distancing remain the best way to control the spread of the COVID-19 virus, but if you must come into contact with other people, you’re safer outdoors than indoors. We all occupy an area in three dimensional space, and as we move away from one another, the volume of air space on which we have an impact expands enormously. “If you go from a 10-ft. sphere to a 20-ft. sphere you dilute the concentration [of contaminated air] eight-fold,” says Dr. Christopher Gill, associate professor of global health at Boston University School of Public Health. That’s important because a single sneeze can project particles a distance of 9 meters, or about 27 feet. The less concentrated those particles are in the air, the less danger they present. “Within seconds [a virus] can be blown away,” Gill says.

Sunlight may also act as a sterilizer, Gill says. Ultraviolet wavelengths can be murder—literally—on bacteria and viruses, though there hasn’t yet been enough research to establish what exactly the impact of sun exposure is on SARS-CoV-2, the virus responsible for COVID-19.

That’s not to say there’s no risk outdoors. People can still cough, sneeze or speak particles into their air space, and especially in a city, the distance between individuals is not always 20 or even 10 feet. In general though, being outdoors in the vicinity of an infected person is safer than being indoors with that person.—Jeffrey Kluger

Correction: The original version of this story said that the atmospheric dilution between a 10- and 20-foot sphere is 1,000-fold. It is eight-fold.

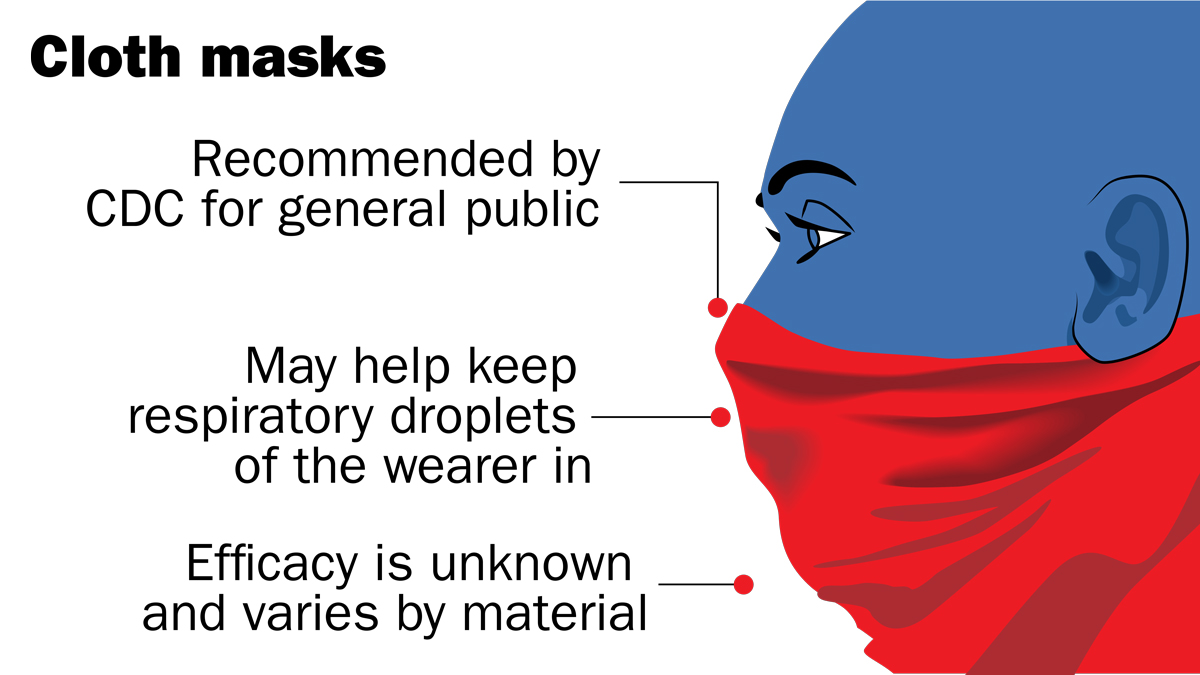

Do face masks work for preventing the spread of COVID-19?

When the new coronavirus first hit the U.S., the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) told people not to wear face masks unless they were sick or caring for someone who was. Masks help capture some of a sick person’s respiratory droplets, which might otherwise spread the virus. In early April, however, the CDC began advising all people to wear non-medical “masks”—any fabric that covers the nose and mouth—when they leave home. The reason for the shift? Scientists now know that many people who are infected with the coronavirus show no symptoms yet can still spread it to others. There’s no way to tell who’s sick and who’s not.

But the efficacy of homemade masks is not scientifically settled. Studies do find that masks can help prevent a sick person from spreading some viruses to others—and may even marginally protect healthy people from becoming ill. “Across these studies, it’s quite consistent that there’s some small effect and there’s no risk associated with wearing masks,” says Allison Aiello, a professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Gillings School of Global Public Health.

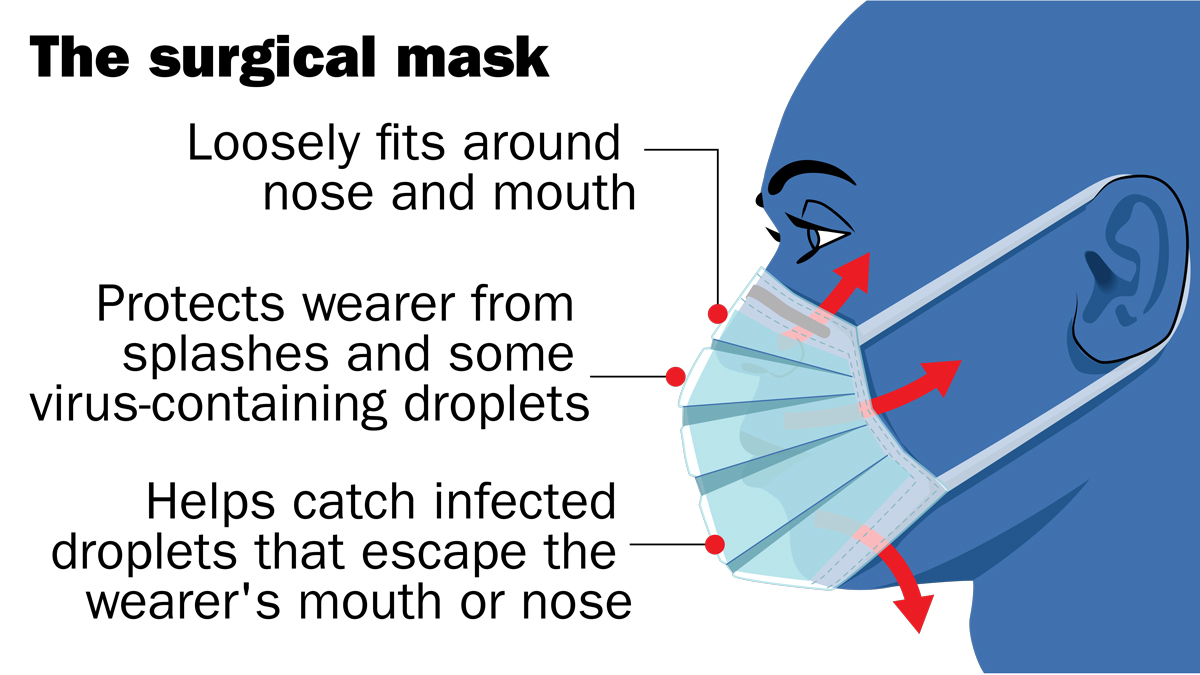

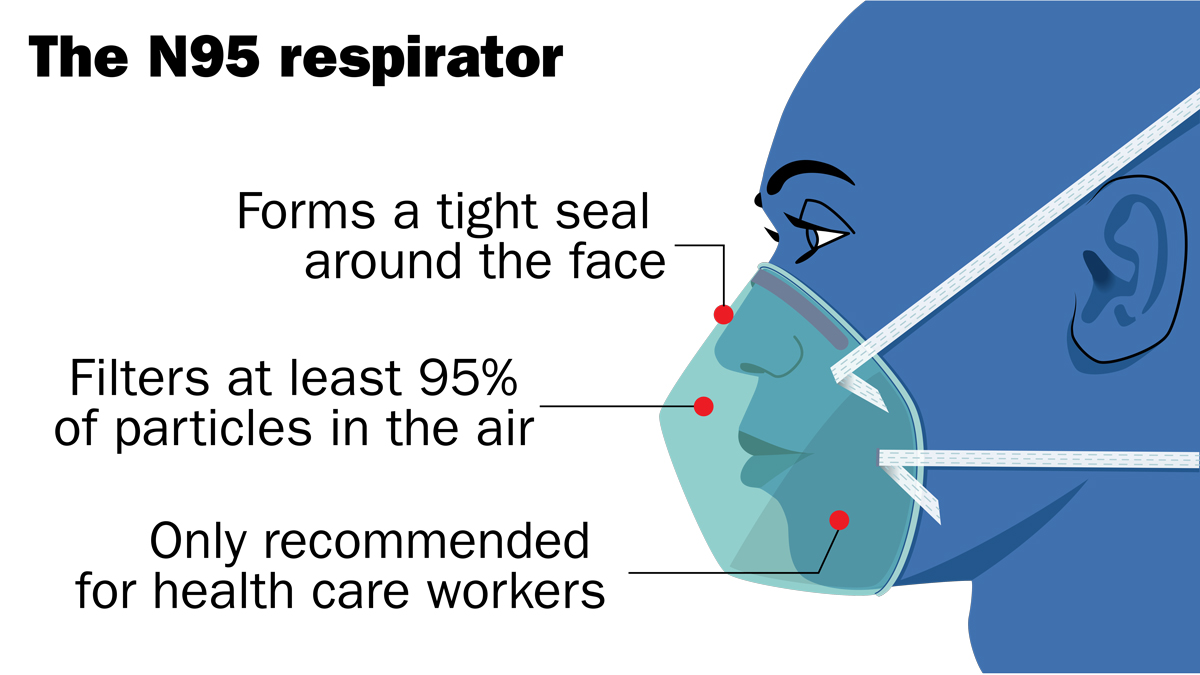

But this research is on surgical masks: loose-fitting masks designed to protect the wearer from outside virus-containing splashes and droplets, and to catch infected droplets that escape the wearer’s mouth or nose.

Neither these nor N95 respirators—tight-fitting facial devices that filter out small particles from the air—are recommended for the general public due to a shortage for health care workers.

It’s unclear if the research on masks would also apply to homemade face coverings, but Aiello and others believe that physical facial barriers are worth wearing during the pandemic even in the absence of strong evidence. As the authors of an analysis published April 9 in the BMJ put it, “In the face of a pandemic the search for perfect evidence may be the enemy of good policy. As with parachutes for jumping out of aeroplanes, it is time to act without waiting for randomised controlled trial evidence.”

Few studies have tested homemade masks. One published in 2013 found that T-shirt masks were about a third as effective as surgical masks at filtering small infectious particles. That’s “better than nothing,” says study author Anna Davies, a research coordinator at the University of Cambridge, but “there’s so much inherent variability in a homemade mask.” Other research found that homemade masks may actually increase the risk of infection if they’re not washed often enough, since damp fabric can breed pathogens.

The bottom line is that wearing a mask is probably a sensible move—as long as you clean it often, wash your hands, refrain from touching your face and continue to keep a safe distance from other people. But there’s not robust evidence that the DIY kind will definitely stop you or others from getting sick.—Mandy Oaklander

For more on masks:

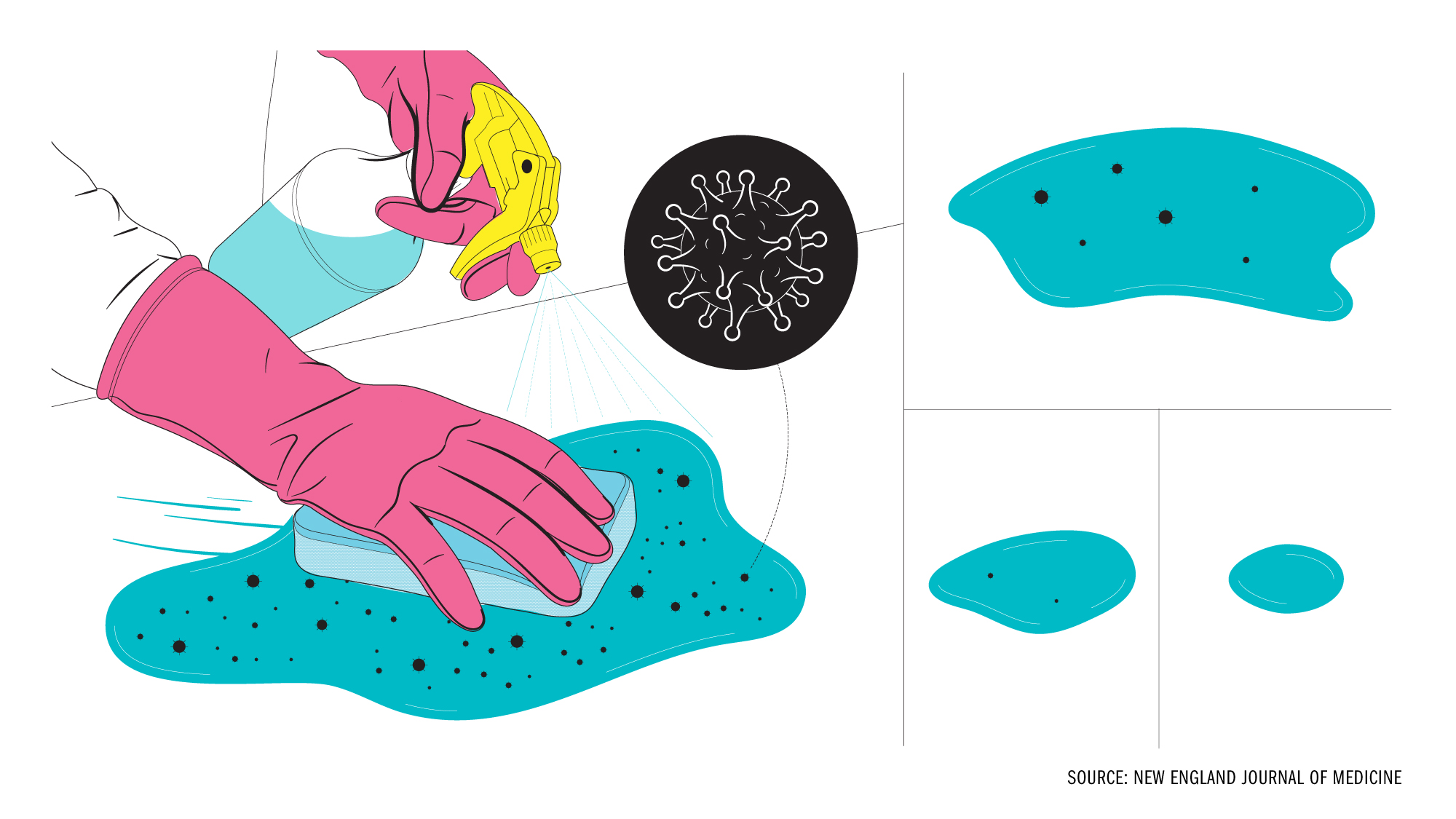

How long does the COVID-19 virus survive on surfaces?

A study published in the New England Journal of Medicine on March 17 found that SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, could last up to four hours on copper, up to 24 hours on cardboard, and two to three days on plastic and stainless steel. Another study published in The Lancet on April 2 found the virus could last for three hours on printing and tissue paper, and up to one day on treated wood or cloth. It also found that the virus lasted three days on glass and banknotes and six days on stainless steel and plastic—far longer than the New England Journal of Medicine study found. Lastly, The Lancet study also found the virus remained on the outside of a surgical mask for seven days.

However, keep in mind these results were produced in a lab. The virus likely breaks down much more quickly in the environment due to its sensitivity to sunlight and temperature, says Dr. Albert Ko, department chair and professor of epidemiology and medicine at the Yale School of Public Health.

It’s also important to remember that scientists don’t know yet how much of the virus someone has to be exposed to in order to become infected, says Jared Evans, a senior scientist at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory. While a certain amount of infectious virus could be on a subway pole, it’s unclear if it would be enough to get a person sick.

Still, experts say wiping down objects as they enter your home, including delivery food containers, is a good way to mitigate risk of exposure.—Madeleine Carlisle

Is there any risk of the COVID-19 virus living on mail & packages?

A study published in the New England Journal of Medicine on March 17 found that SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, could live up to 24 hours on cardboard. A study published in The Lancet on April 2 found that it could last up to three hours on paper. But keep in mind that the virus will likely break down more quickly outside of a laboratory, due to real-world exposures like sunlight, wind and temperature, experts say.

So yes, there is likely some risk that the virus could be on your mail, but it’s a small one. “A letter that’s been mailed to you and been traveling through the postal service for a couple of days, the virus will be off of that,” says Jared Baeten, professor of global health, medicine and epidemiology at the University of Washington. The risk comes when the carrier handles your mail and brings it to your door, potentially exposing it to the virus again.

The infectious dose of the virus—the amount a person has to be exposed to in order to become infected—is still unknown, says Jared Evans, a senior scientist at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory. So even if the virus is on a package, it might not be enough to get you sick.

Still, out of an abundance of caution, Matthew Freeman, an associate professor of environmental health, epidemiology and global health at Emory University Rollins School of Public Health, recommends opening your package or mail outside your house, disposing of the box or envelope, coming back inside and immediately washing your hands. If you want to be even more thorough, you can also wipe down the contents of a package and then wash your hands again, although it’s quite unlikely the virus will have survived. Crucially, you should make sure to stay at least 6 feet away from the mail carrier at all times.—Madeleine Carlisle

What should I do to shop safely?

When shopping, the safest thing you can do is stay 6 feet away from other people at all times, experts tell TIME. Be patient. If you see a crowded aisle, wait or come back later. While there’s a chance the virus could be transmitted on a surface, “you’re most likely to get this from another person,” says Dr. Lauren Sauer, an assistant professor of emergency medicine at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. Try to shop somewhere that already enforces social distancing, such as making people stand 6 feet apart in line. Also try to go to the store at “off-peak hours” and be respectful of the hours set aside for high-risk individuals. Ordering groceries online can also be a good option, especially if you’re in a high-risk category, experts say.

But if you must go to the store, a spokesperson for the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends cleaning your shopping cart or basket—specifically the handles and other surface areas—with disinfectant wipes. Sauer also recommends using a paper shopping list, rather than your phone, while you’re in the store, because “the less you can touch your personal items in public spaces, the better.”

Once you’ve touched an item in the store, assume your hands may have been contaminated, experts say. Touch as few things as possible and don’t touch your eyes, nose or mouth. Bring hand sanitizer and use it often. You don’t need to wear gloves, because they don’t stop you from spreading the virus to your face. However, the CDC does recommend wearing a non-medical mask to reduce the risk of inadvertently spreading the virus to others.

When you go to pay, try to have as little contact with the cashier as possible. As soon as you can, make sure to wash your hands using soap and water for at least 20 seconds.

The CDC spokesperson says that “[currently] there is no evidence to support transmission of COVID-19 associated with food or food packaging.” Still, if you want to reduce your risk of exposure even more, you can wipe down your groceries when you get home. Make sure to avoid getting hazardous chemicals on food; just wash your fruits and vegetables like you normally would. Once you unload your groceries, the CDC recommends washing your hands again and cleaning kitchen surfaces like countertops, cabinet handles and light switches.—Madeleine Carlisle

Is there any risk with food delivery services?

The dangers posed by food delivery do seem to be minimal. A spokesperson for the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention told TIME on March 27 that “[currently] there is no evidence to support transmission of COVID-19 associated with food or food packaging.”

That said, the same precautions you would take for a package delivered to your home should be applied with food deliveries. John Swartzberg, a clinical professor emeritus of infectious diseases and vaccinology at the University of California, Berkeley School of Public Health, recommends first bringing the container inside, washing your hands, wiping the container down with soap and water or a disinfectant, washing your hands again and only then then putting the contents of the the container onto your plate. Also, don’t make the precautions you take a danger by themselves: Make sure to avoid getting cleaning chemicals on anything you eat. He also stressed you should make sure to stay at least 6 feet away from the delivery person, and recommends having them set the food down at the door and leave before you come out and get your delivery.—Madeleine Carlisle

For more on food delivery and shopping:

Should I worry about my clothes after I’ve been outside?

That depends on where you go and whether you’re in contact with other people. Recent studies have found that the virus that causes COVID-19 can live in the air and on different types of surfaces for between four hours and 72 hours. An April 2 study from The Lancet shows that the virus can live on cloth fabric for up to two days; on surfaces like steel or plastic, it can be detected for up to seven days.

That said, it’s unlikely that you’ll get sick from not changing your shirt after returning home from the grocery store, says Dr. Irfan Hafiz, an infectious disease specialist at Northwestern Medicine. You’re more likely to get it through respiratory droplets from another person than contracting it from a surface.

If you are caring for someone who is sick, you should be careful and protect yourself while handling their belongings. “Their personal environment may be more contaminated,” says Hafiz. It’s okay to mix their clothes with your dirty laundry before washing them; just make sure to wear gloves during or wash your hands after doing the laundry.—Mahita Gajanan

Does rain wash away the COVID-19 virus?

Rain dilutes the virus and can also physically wash it off a surface just like “dirt can wash away,” says Jared Baeten, professor of global health, medicine and epidemiology at the University of Washington. However, experts don’t believe rain deactivates the virus or disinfects surfaces the way soap and water does.

Scientists don’t yet know how much of the virus you have to be exposed to in order to be infected, says Jared Evans, a senior scientist at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory. So it’s unclear whether the already limited impact rain would have on viruses living on the surface of, say, the bannister of your front steps, would make a difference in whether or not the bannister is safe to touch.—Madeleine Carlisle

Can I get COVID-19 more than once?

News reports out of East Asia have said that some patients in China, Japan and South Korea who were diagnosed with COVID-19 and seemingly recovered then tested positive again days or weeks later. One study—not peer-reviewed—on recovered COVID-19 patients in the southern Chinese city of Shenzhen, found that 38 out of 262, or almost 15% of the patients, tested positive after they were discharged.

However, experts say that these are likely not instances of re-infection. Instead, it’s most likely the case that the post-recovery positive tests simply found lingering infections that were not detected by earlier tests. A positive test after recovery could be detecting the residual viral RNA that has remained in the body, but not in high enough amounts to cause disease, says Vineet Menachery, a virologist at the University of Texas Medical Branch.

Experts say the body’s antibody response, triggered by the onset of a virus, means it is unlikely that patients who have recovered from COVID-19 can get re-infected so soon after contracting the virus. But as with so much about COVID-19, this is the current best guess, not yet settled science. A scientific brief from the World Health Organization published on April 24 emphasizes that “there is currently no evidence that people who have recovered from COVID-19 and have antibodies are protected from a second infection.”

Based on what’s known about other coronaviruses, Menachery estimates that COVID-19 antibodies will remain in a patient’s system for “two to three years.” (One Taiwanese study on the 2003 outbreak of SARS, which is caused by a virus that is similar to the one that causes COVID-19, found that survivors had antibodies that lasted for up to three years.) But more research is required to determine whether COVID-19 antibodies confer immunity, and for how long, according to the WHO.

—Hillary Leung

If I get COVID-19 and recover, am I immune and safe to be around/help out older family and neighbors?

The messages are mixed on this one. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines for COVID-19 patients who have recovered clears them to break quarantine if all of the following conditions have been met:

(The full CDC guidelines are here.)

But the science is still unsettled on whether recovering from the virus confers immunity. As TIME has reported, there have been cases in Japan, China and South Korea in which patients who seemingly recovered were readmitted to the hospital with a COVID-19 relapse. Some of these presumably recovered patients tested positive again, but it is unclear whether they were actually reinfected or if apparently negative tests simply failed to detect low, lingering levels of the virus. The World Health Organization has also said that “there is currently no evidence that people who have recovered from COVID-19 and have antibodies are protected from a second infection.” Until more is known with certainty, it is thus best for recovered patients to continue avoiding elderly people or members of other susceptible groups.—Jeffrey Kluger

I’ve been social distancing for two weeks. When is it safe for me to go see family?

No one knows exactly how long it will take, but experts say not yet, at least in the U.S.

As of April 13, forty-two states and the District of Columbia (covering about 97% of the U.S. population) had imposed shutdowns and stay-at-home guidelines. Millions of Americans have been social distancing since mid-March, and, as of early April, the national infection curve has not yet flattened. The rules on social distancing are, for now, open-ended, with policies likely to remain in place in one form or another for months, not weeks or days.—Jeffrey Kluger

Can my dog or cat get COVID-19?

A family dog in North Carolina has tested positive for SARS-CoV-2—the virus that causes COVID-19 in humans—Duke University researchers confirmed to TIME. The dog was tested as part of Duke’s Molecular and Epidemiological Study of Suspected Infection, and is believed to be the first dog in the U.S. with a confirmed case of the virus.

The dog’s diagnosis comes after the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) confirmed on April 22 that officials had diagnosed the first two cases of SARS-CoV-2 in pets in the country. Two cats living in separate areas of New York State developed a mild respiratory illness, but both are expected to make a full recovery.

Still, the CDC says that there’s little-to-no risk of pets transmitting the virus to humans, given that there is no specific evidence showing this type of transmission has ever happened. Not including the dog and two cats in the U.S., globally only two dogs and two other cats have tested positive for the virus, according to the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA). “That’s why in the U.S. we’re really not pushing hard to test pets at all,” says William Sander, assistant professor of preventive medicine and public health at the University of Illinois’ College of Veterinary Medicine.

A tiger at the Bronx Zoo tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19 in humans, but, says Karen Terio, chief of the Zoological Pathology Program at the University of Illinois’ College of Veterinary Medicine, “A tiger is not a domestic cat, they are a completely different species of cats. To date we have no evidence of the virus being transmitted from a pet to their owners. It’s much, much more likely that an owner could potentially transmit it to their pet.”

In the case of one of the New York cats diagnosed with the virus, the cat’s owner had tested positive for COVID-19 before the cat showed any signs of illness. In the case of the second cat, no individuals in its household were confirmed to be ill from the virus. The CDC says the second cat was likely infected by either a mildly ill or asymptomatic household member or through contact with an infected person outside its home. The North Carolina dog belongs to a family participating in an ongoing Duke University study examining how the body responds to COVID-19. The mother, father and son from the family all reportedly have confirmed cases of COVID-19.

Terio adds that there is still much that is unknown. If your pet, for example, did contract the virus, it is not clear whether signs of infection would show themselves in the way they do in humans. Out of caution, the CDC and AVMA recommend that sick humans stay away from their animal companions. “Just like you’re keeping your distance from other people, try to have somebody else in your house take care of your pet, just to be overly cautious,” Sander says. If you are sick or showing symptoms and you have to take care of your pet, the CDC recommends avoiding snuggles or touching your pet, and washing your hands thoroughly before and after feeding.

After the diagnoses of the two New York cats, the CDC offered additional guidance: Keep cats indoors when possible to keep them away from other animals and people. And for dogs, keep them on a leash and at least 6 feet away from other animals and people, and avoid dog parks or public places where large amounts of people and dogs gather.

—Jasmine Aguilera and Madeleine Carlisle

Can the COVID-19 virus live on my pet’s fur?

Studies have shown that SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, can live on a variety of surfaces for several hours or days. But none have tested dog or cat fur.

In an email to TIME, the American Veterinary Medical Association stated that while the virus can be transmitted by touching a contaminated surface or object and then touching your nose, mouth or eyes, “this appears to be a secondary route. In addition, smooth, non-porous surfaces such as countertops and doorknobs transmit viruses better than porous materials; because your pet’s hair is porous and also fibrous, it is very unlikely that you would contract COVID-19 by petting or playing with your pet. However, it’s always a good idea to practice good hygiene around animals, including washing your hands before and after interacting with them.”—Jasmine Aguilera

Do flies, mosquitoes, or other insects carry or transmit the virus?

Short answer: no, you cannot get COVID-19 though insect bites. “There are viruses that are transmitted by mosquitoes; this is not one of those,” says Karen Terio, chief of the Zoological Pathology Program at the University of Illinois’ College of Veterinary Medicine.

William Sander, assistant professor of preventive medicine and public health at the University of Illinois’ College of Veterinary Medicine, adds that previous studies of other types of coronaviruses determined that insects are not a viable mode of transmission.

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19 disease, is primarily spread from person to person by coming in contact with an infected individual’s respiratory droplets, for example saliva or mucus.—Jasmine Aguilera

Can cleaning products kill the COVID-19 virus?

Probably, as long as you use them right. Household cleaning products designed to fight viruses—i.e., not those labeled exclusively “antibacterial”—typically work against known coronaviruses, like strains that cause the common cold. So while most household products haven’t been tested specifically against the novel coronavirus strain that causes COVID-19, it’s safe to assume standard wipes and sprays will work pretty well against it, says Dr. Aaron Glatt, chief of infectious disease at Mount Sinai South Nassau in New York.

But cleaning properly takes a little patience. “Some of these [products] don’t work by contact,” Glatt says. “They work by being on the surface for a while and drying via air.” For peak efficacy, use enough of a product to leave a surface wet for up to several minutes, then let it dry on its own. Read each product’s label to make sure you’re using enough.

Don’t feel like you need to clean your home obsessively, though; if you’re social-distancing properly and washing your hands often, you don’t need to deep clean all the time, experts say. Regular upkeep, and periodically wiping down high-touch objects like light switches and doorknobs, should keep your home sufficiently clean.—Jamie Ducharme

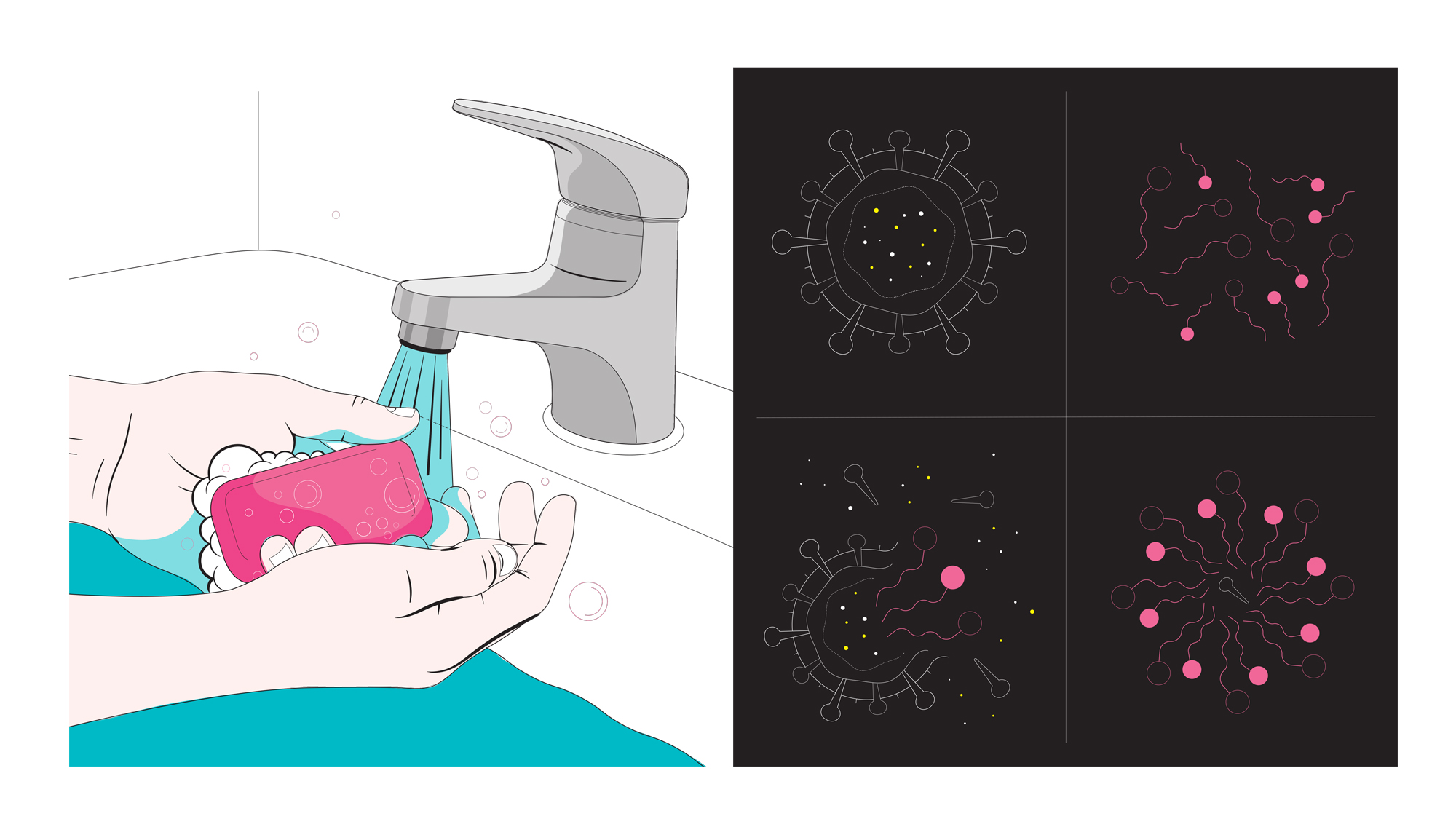

Does it matter what type of soap I use to wash my hands?

Probably not. Any kind of soap, used properly with water for the recommended 20 seconds of handwashing, will work to remove SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, from your hands. And since we’re dealing with a virus, antibacterial soap doesn’t do anything extra to help.

Soap has a hydrophobic end (meaning it repels and doesn’t mix with water) that binds with oils, and breaks down the oily lipid molecules that make up the membrane of SARS-CoV-2, according to Dr. Mary Stevenson, an assistant professor of dermatology at NYU Langone Health. The virus breaks apart and becomes trapped in the soap bubbles, which wash away in the water.

Stevenson recommends washing your hands in lukewarm water. Extremely hot water is more likely to harm your skin, and doesn’t do anything extra to kill the virus. A lukewarm temperature will keep your hands comfortable and strip away less moisture. Once you’re done washing, it is important to dry your hands on a clean towel. Cloth or paper towels both work well; if you’re at home, Stevenson advises keeping a rotation of clean hand towels that are traded out and washed at least once a day to avoid wasting disposable towels. If you’re washing your hands in a public restroom, use a clean and dry paper towel.—Mahita Gajanan

What’s the safest way to do laundry in a shared/public laundry room?

If you’re not ill, continue doing your laundry as you normally would. For some people, that means taking loads of dirty clothes to a laundromat or shared laundry room, leading to potential exposure to the coronavirus or the risk of infecting others.

In these situations, stick with your typical laundry routine but also be sure to follow guidelines from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to prevent the spread of COVID-19: keep a distance of at least six feet from others in the laundry facility, wash your hands after touching any surfaces, and wear a cloth face mask. When doing your laundry, avoid shaking out your dirty clothes; if your clothes do have any of the virus on them, shaking them could disperse the virus into the air.

If you’re taking care of someone who is sick, it’s safe to mix their dirty clothing with yours before washing, per the CDC; just make sure to wear gloves or immediately wash your hands with soap after handling the laundry.

Ideally, you can drop your laundry into the washer and leave the facility (like go for a walk or wait in your car) until your clothes are ready to go into the dryer, says Dr. Irfan Hafiz, an infectious disease specialist at Northwestern Medicine. Be sure to dry your clothes thoroughly; the heat from the hot water and dryer should “clear off any of the virus that’s there,” says Hafiz.

And once your clothes are dry, fold them at home; avoid using communal folding tables in shared spaces since you don’t know if dirty clothes have been on those surfaces previously.

The CDC also advises that people clean and disinfect their clothing hampers, or to place a disposable bag liner in the laundry baskets to further prevent the spread of COVID-19.—Mahita Gajanan

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com