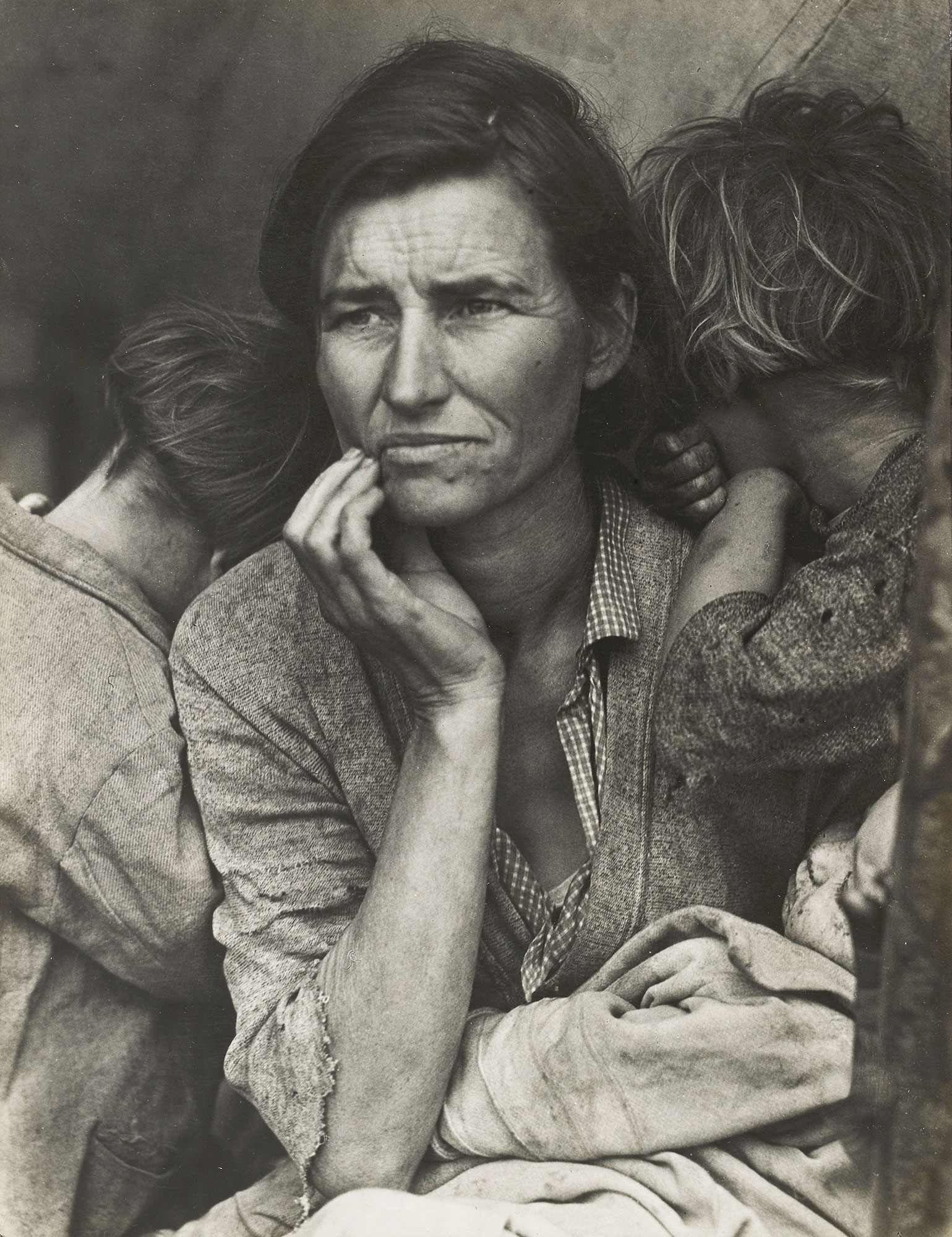

Dorothea Lange was eager to go home. After a month in the field in central California in March 1936, the photographer drove 20 miles past a sign that read PEA-PICKERS CAMP before a nagging feeling caused her to turn back. The decision resulted in a picture of 32-year-old Florence Owens Thompson and three of her children, which came to be known as Migrant Mother. It remains the most indelible image of the Great Depression, and is now one of the most famous photographs ever made. The photo prompted the government to respond to prevent starvation at the camp, and it was shown at the Museum of Modern Art’s first photography exhibition, in 1940.

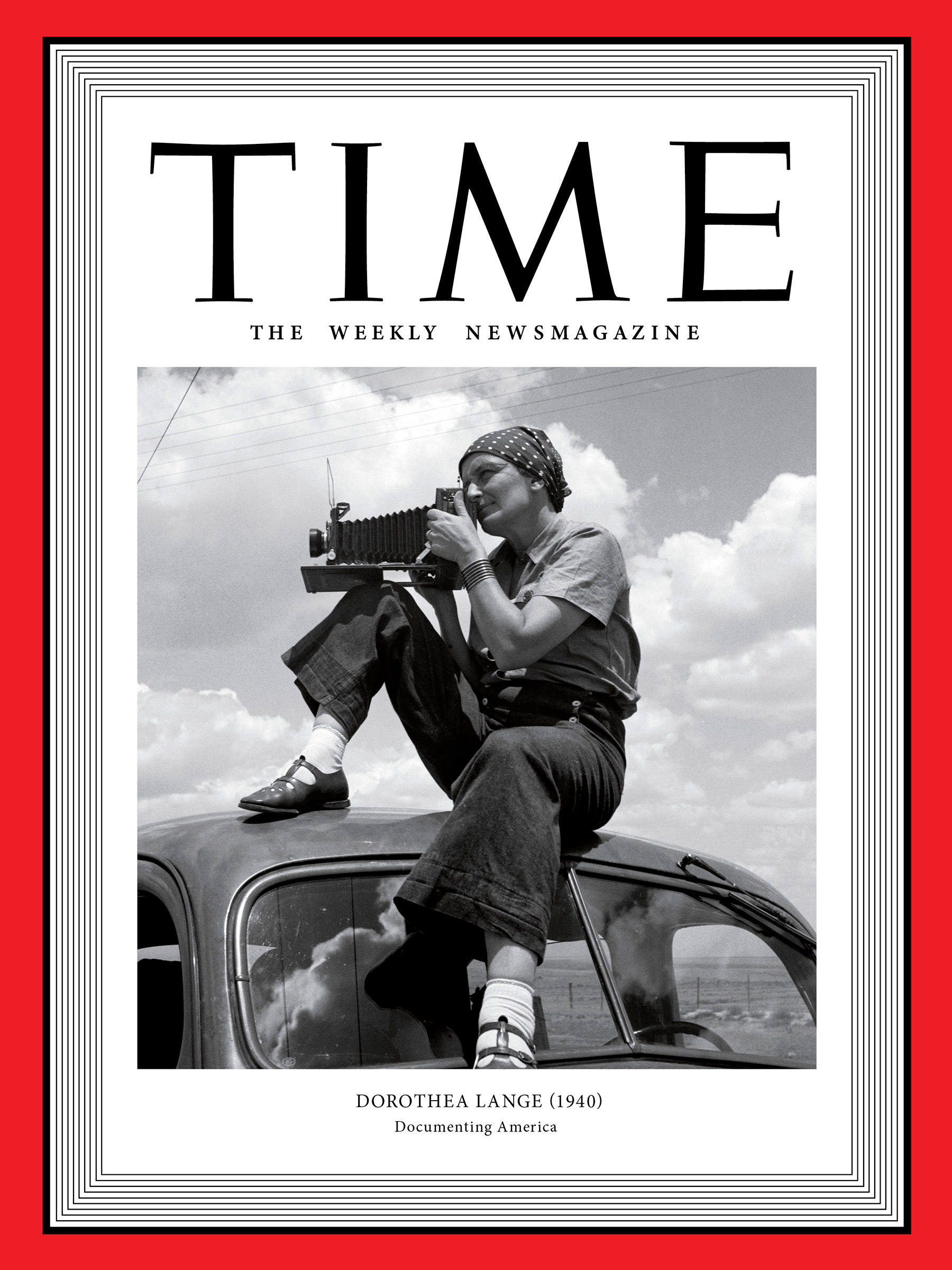

1940, incidentally, was also the year Lange was fired from her position with the Farm Security Administration for being “uncooperative.” (For one thing, she refused to follow orders to train her lens primarily on white Americans, whose suffering, it was assumed, would engender more support.) She proved incorrigible: two years later, on assignment for the War Relocation Authority to photograph Japanese-American internment camps, she made images that were searingly critical of the policy, which were suppressed until after the war.

Lange was uniquely suited to wield her camera as a tool to inspire social change by putting a human face on suffering—work she carried on for three decades following the creation of her best-known image. Contracting polio as a child had left her with a limp that helped her relate to outsiders; early work as a portrait photographer trained her to capture subjects’ dignity. Since her death in 1965, her work has been appreciated as much for its value as art as for its documentation of history, though Lange disapproved of her photos’ being divorced from context, preferring captions that captured her subjects’ voices. As she put it in an interview not long before her death, “My powers of observation are fairly good, and I have used them.” —Eliza Berman

This article is part of 100 Women of the Year, TIME’s list of the most influential women of the past century. Read more about the project, explore the 100 covers and sign up for our Inside TIME newsletter for more.