In a two-part series, art photographer Mark Steinmetz and Charlotte Cotton review the Museum of Modern Art’s latest opus – Photography at MoMA: 1960 – Now. They offer contrasting views about the Museum’s curatorial choices as the institution moves away from John Szarkowski’s legacy. Read Cotton’s take here.

So many of the photographs in the newly released “Photography at MoMA: 1960 – Now” feel like illustrations of ideas. A large number of them interrogate, in one way or another, the medium of photography or the role of mass media representations in society. Fewer might be considered interrogations of the world that we actually live in as it actually looks and fewer still could be considered interrogations of the self.

The selection is tilted towards photographs about thoughts, not feelings; by and large these are photographs that are carriers of ideas.

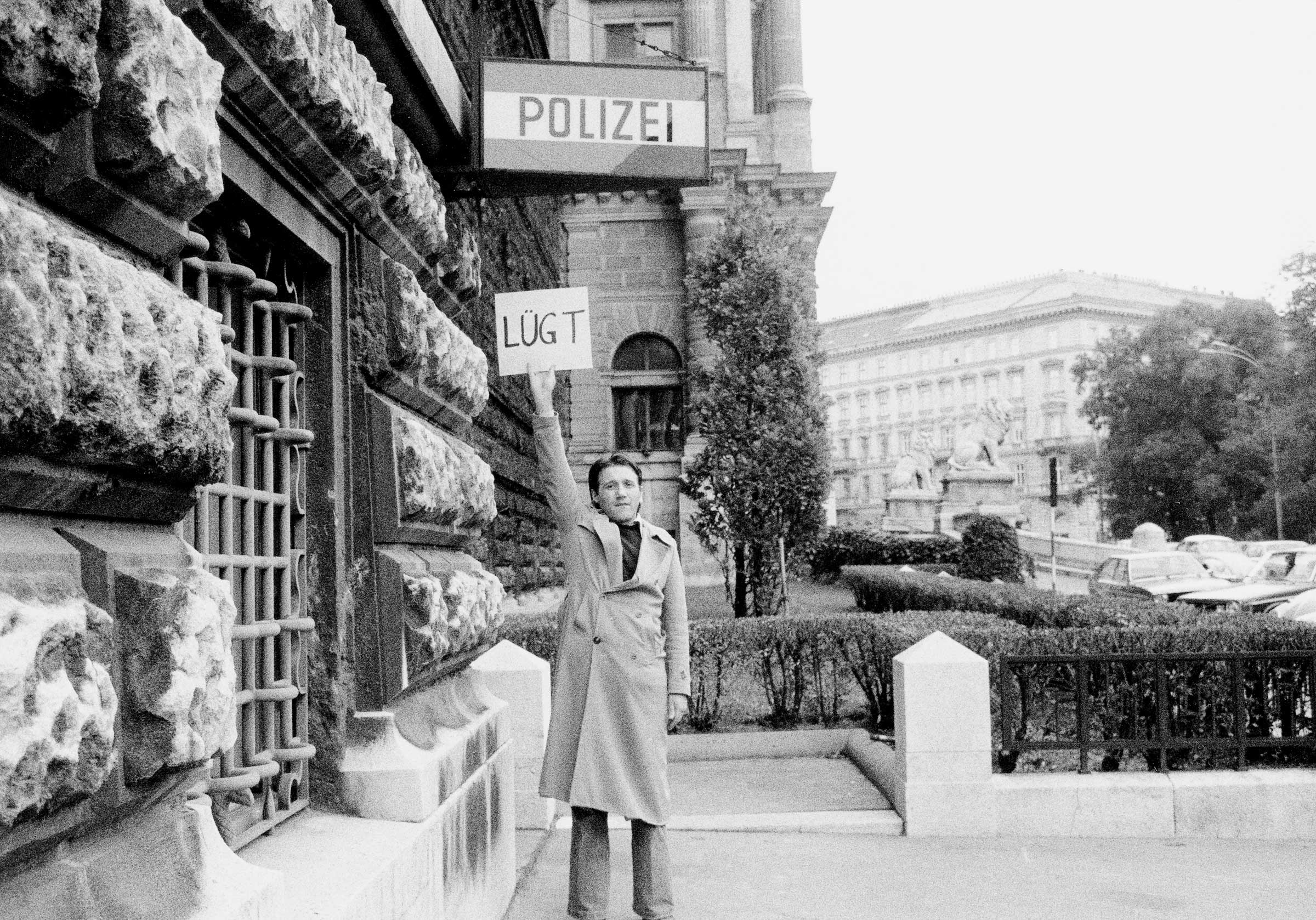

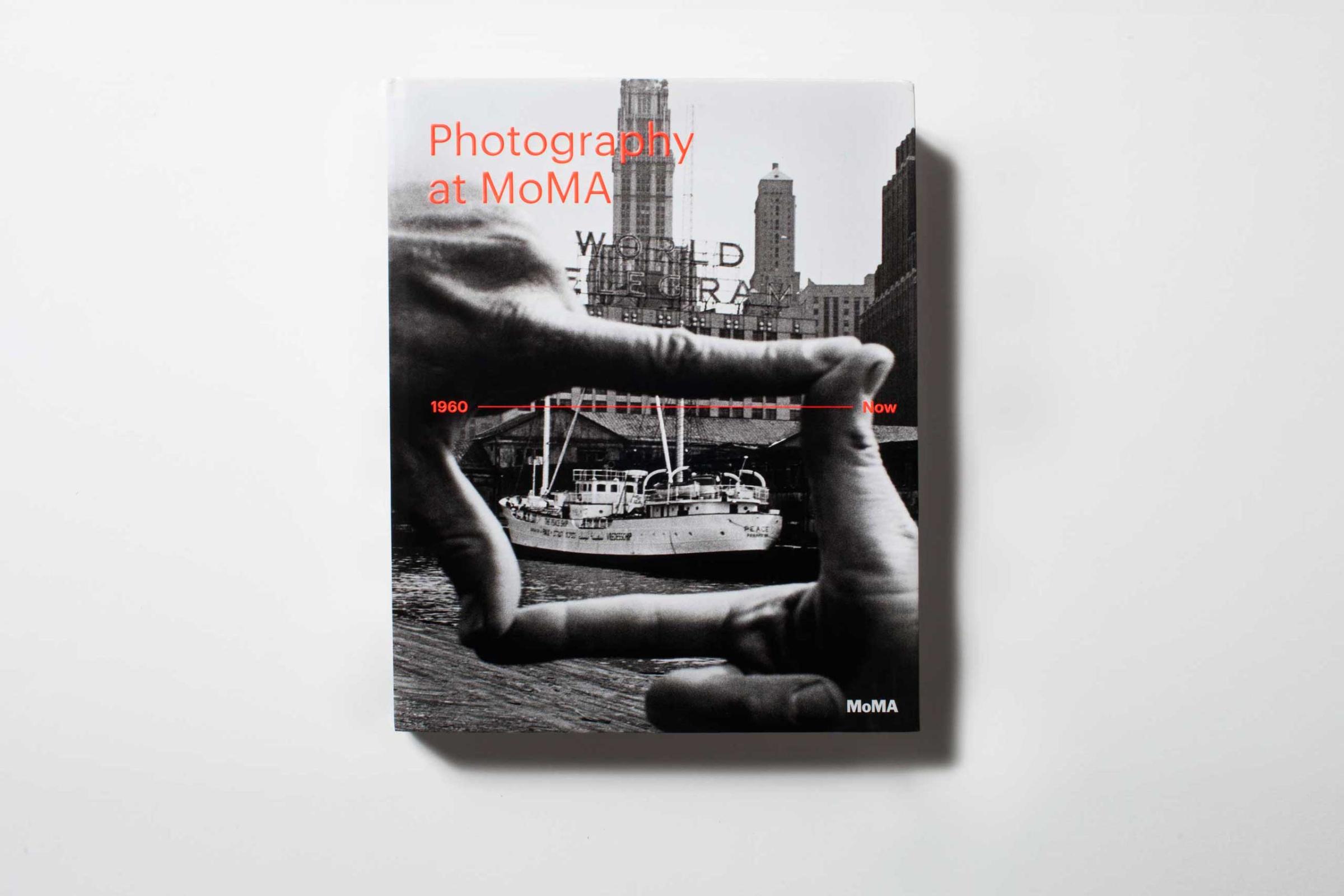

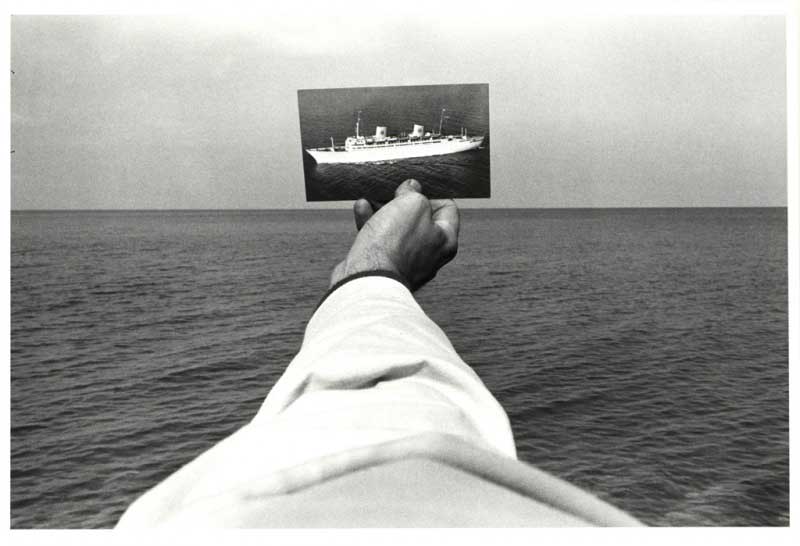

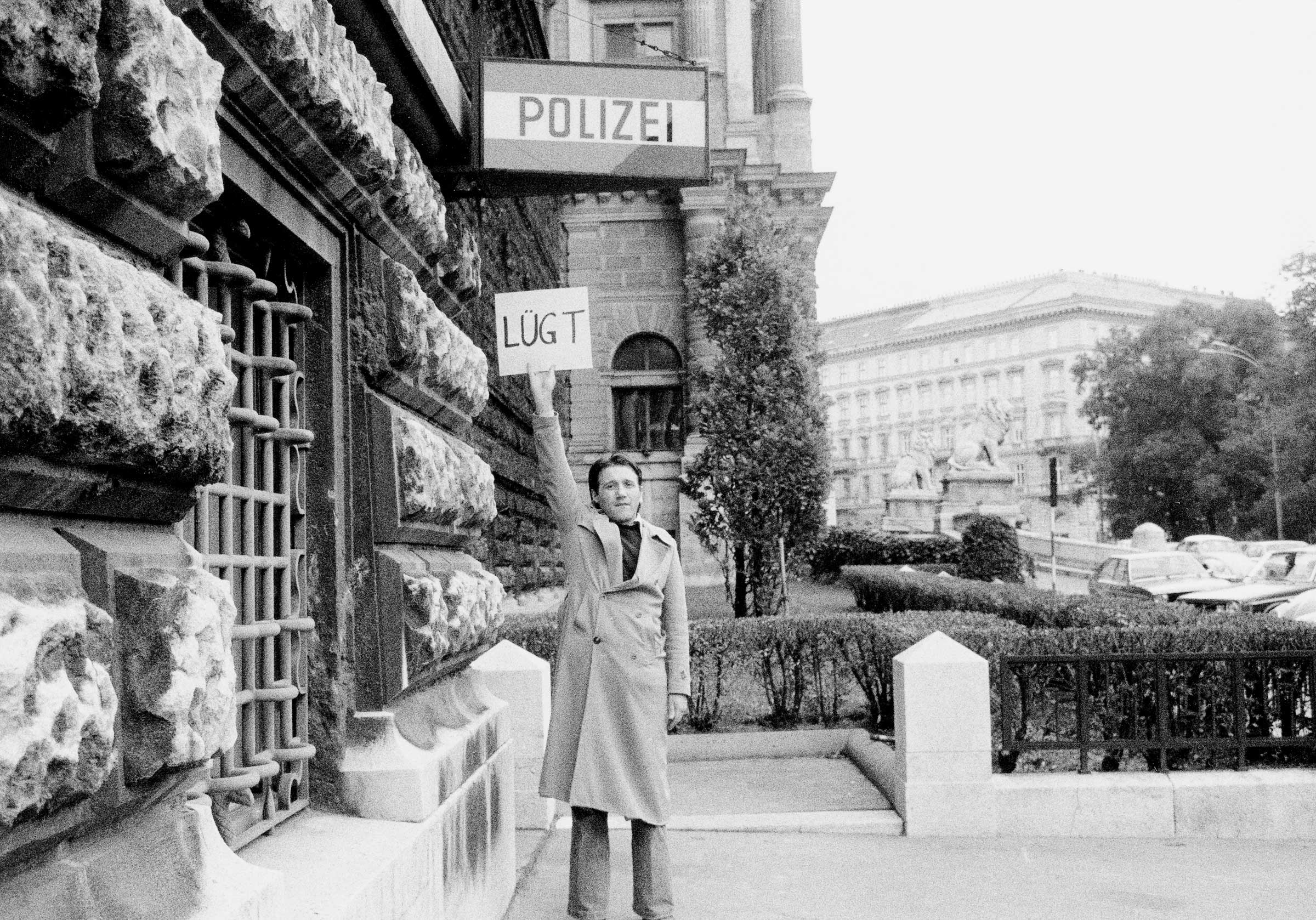

The book’s cover photograph, which was made by a pair of European photographers, Harry Shunk and János Kender, is attributed to John Baldessari, who presumably provides the hands in “Hands Framing New York Harbor, 1971.” The Shunk-Kender choice for cover signals a move towards selecting many more non-American photographers and also towards non-traditional approaches, such as collaborations among artists. It is reminiscent of earlier work by Kenneth Josephson who photographed postcards he held out at arm’s length. Josephson’s work had been included in at least two major books by John Szarkowski, a former director of photography at MoMA, but does not appear in this version, perhaps because the new curators are distancing themselves from Szarkowski’s legacy.

In his introduction, the present chief curator at MoMA, Quentin Bajac, quotes the historian John Tagg, who called Szarkowski’s work at MoMA, “a programme for a peculiar photographic modernism.” Bajac does not spell out exactly what Tagg means by the word “peculiar” nor does he make clear the extent to which he is in agreement.

In a 1975 essay, “A Different Kind of Art”, Szarkowski discusses the difficulty art audiences typically have with straight or un-manipulated photography: they are used to seeing the hand of the maker in an artwork (see again the cover image.) But in the best modernist photography, the kind that Szarkowski championed when other museums were not, from Atget to Robert Adams, the handiwork of the artist is carefully hidden.

In this book, the real enthusiasm of the new curatorial staff seems to be for photo-based art: there are chapters on conceptual art, performance art, staged photography, work drawn from archives, and abstracted, experimental art. Most of the younger artists and the recently collected work are in this vein. The current curators give the impression that they are content to let straight photography rest pretty much with the same set of photographers that Szarkowski chose for his book, “Photography Until Now (1989),” that is to say, with the generation of photographers who are now in their sixties and seventies. They’ve included a few younger photographers who work in an un-manipulated manner, but the ones they’ve chosen come from other continents and work with some sort of easily graspable political agenda. For the most part the curators’ interest in recent straight photography appears to be slight.

The number of photos in this book where the camera is used for casual note-taking seems unduly large. The vantage point is neutral; the craft is “de-skilled,” to use a word curator Roxana Marcoci uses to describe Ed Ruscha’s impersonal approach. So many of the book’s photos were made either under studio lights or indoors often without a detectable source of light. A surprising number of the outdoor photos selected seem oddly muted as well, as if stronger light would just get in the way. The light has been neutered. Few images feel buoyant; few feel intimate. Many have an experimental, laboratory-type feel or are modern day iterations of the design-driven Bauhaus – sometimes sparks are set off and some of the pictures do have flare; many are serial/sequential.

I am generalizing I hope not too horribly, but, aside from a chapter on documentary practices after Frank’s “The Americans,” the overall emotional climate of the collection is cool and overcast. Where are the shadows? Where is the light?

Cartier-Bresson suggested to a previous generation of photographers that they read “Zen in the Art of Archery,” to cultivate the pause, the spaciousness, that the zen archer draws from before releasing his/her arrow. But what good is this advice to a generation that is mostly indifferent to the role timing can play in photography? Few photos in this collection could be called sensuous. The ability to see beauty where others do not has taken a back seat to other concerns. There is also scant attention paid to the photographer as auteur, who views photography as a kind of cinematic literature. Could there not be a way to address the exciting boon in photography books of the past fifteen years?

There is more than one kind of photography and these different approaches deserve examination but in putting so much emphasis on photo-based art rather than on clear photographs that describe the photographer’s reactions to the world the museum waters down its legacy to too great an extent.

Mark Steinmetz is an art photographer based in Athens, Georgia.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com