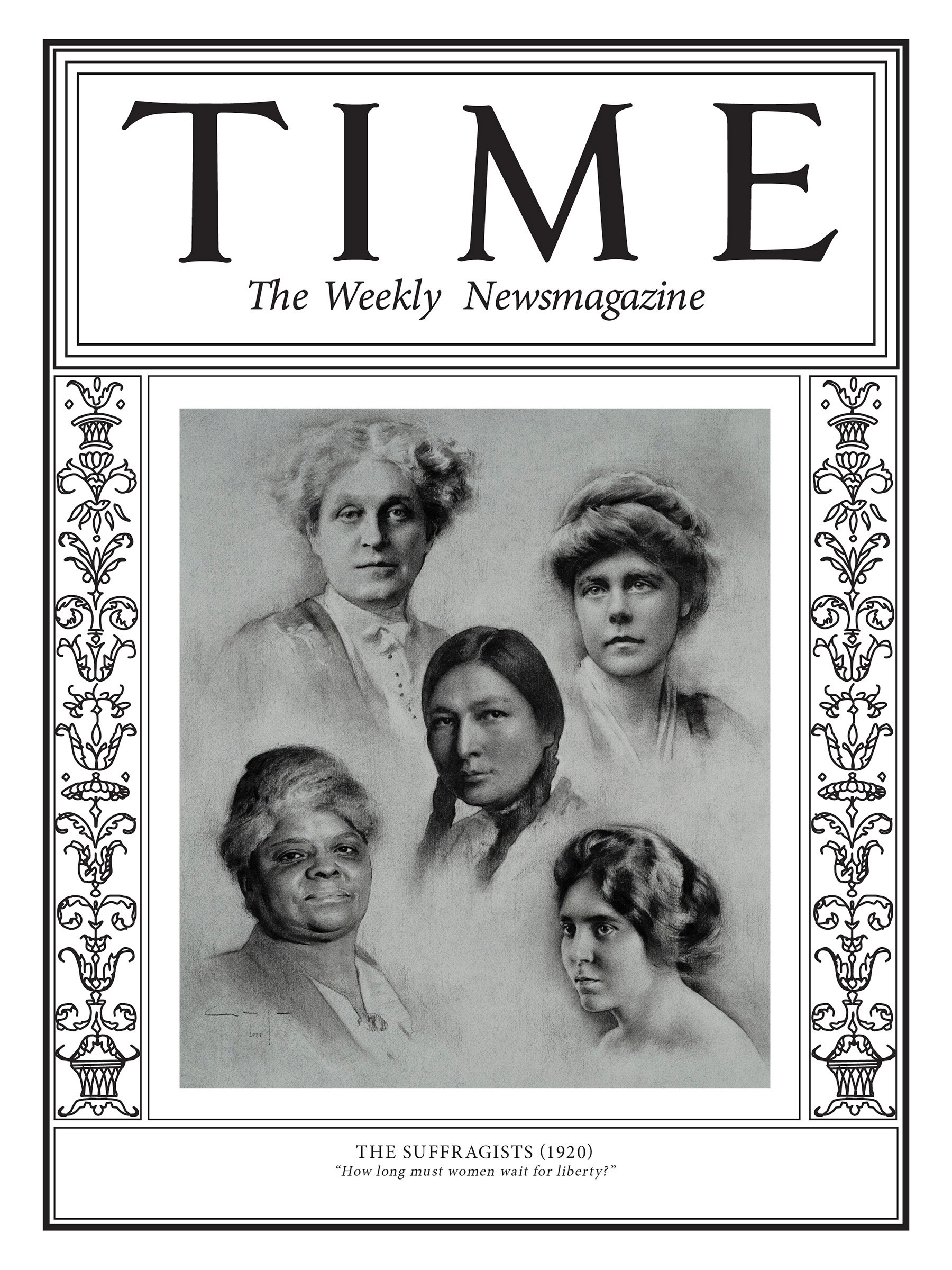

It was the culmination of generations of activism, and Carrie Chapman Catt, who had devoted three decades to the suffrage struggle, was among the crowds that celebrated the ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920. “Women have suffered agony of soul which you never can comprehend, that you and your daughters might inherit political freedom,” Catt told a victorious throng. “Prize it!”

Among those agonies was an ongoing debate about how women should go about securing those rights—and the ongoing disenfranchisement of women of color.

Catt opted for pragmatism and politics, lobbying on a state level and in the halls of Congress. Along the way, she tussled with Alice Paul and Lucy Burns, militant suffragists who preferred a more dramatic approach. Paul and Burns organized public parades and staged a groundbreaking, years long White House picket with banners that implored President Woodrow Wilson to act. The “Silent Sentinels” endured arrests and imprisonment in a squalid workhouse where they were brutalized and force-fed. Which approach was more effective? “Every movement for social change needs both,” says suffrage historian Johanna Neuman.

For women of color, though, the 1920 victory did not guarantee voting rights. Despite their fervent participation in the suffrage struggle, their voting rights were secured only with the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

Native Americans like Zitkala-Sa, a member of the Yankton Dakota Sioux, were not considered U.S. citizens and were not qualified to vote. “Americanize the first American!” she urged in 1921. Even after the Indian Citizenship Act she had lobbied for became law in 1924, it did not guarantee the vote. Zitkala-Sa agitated for full voting rights for the rest of her life. Only in 1962, decades after her death, did Native Americans gain the right to vote from every state legislature.

The 19th Amendment was also bittersweet to black suffragist Ida B. Wells-Barnett. “With no sacredness of the ballot there can be no sacredness of human life itself,” she wrote in 1910, tying women’s right to vote to Jim Crow disenfranchisement of black men. Despite her contributions to the movement, Wells-Barnett was snubbed by white activists. At a 1913 suffrage parade, she was told to march in the rear. She rebelled, claiming a spot alongside white participants instead.

“This part of the suffrage story is a tragic one,” says Wells-Barnett biographer Paula Giddings. “It’s time to re-examine the movement and its flaws so we won’t repeat them again.”—Erin Blakemore

Blakemore is a journalist and the author of The Heroine’s Bookshelf

This article is part of 100 Women of the Year, TIME’s list of the most influential women of the past century. Read more about the project, explore the 100 covers and sign up for our Inside TIME newsletter for more.