One of the first things Tom Mauser did when he learned that two mass shootings had killed more than 30 people within 24 hours was warn his wife not to turn on the television.

News that nine people were fatally shot at a nightlife entertainment hub in Dayton, Ohio—hours after 22 others were killed at a shopping complex in El Paso, Texas, over the weekend—would be another painful reminder of the day the Mausers’ 15-year-old son Daniel was murdered at Columbine High School in 1999.

“It’s a gut punch,” Mauser, 67, says of the double massacres.

The moments immediately following his child’s death two decades ago are now blurry in his mind, says Mauser, who only remembers how traumatic it all felt. But other family members of mass shooting victims recall utter chaos, having to plan a funeral, comfort relatives, greet well-wishers, field media requests and seek answers from authorities—all while grappling with a new and excruciating type of pain that some say is worsened each time another mass shooting unfolds in America.

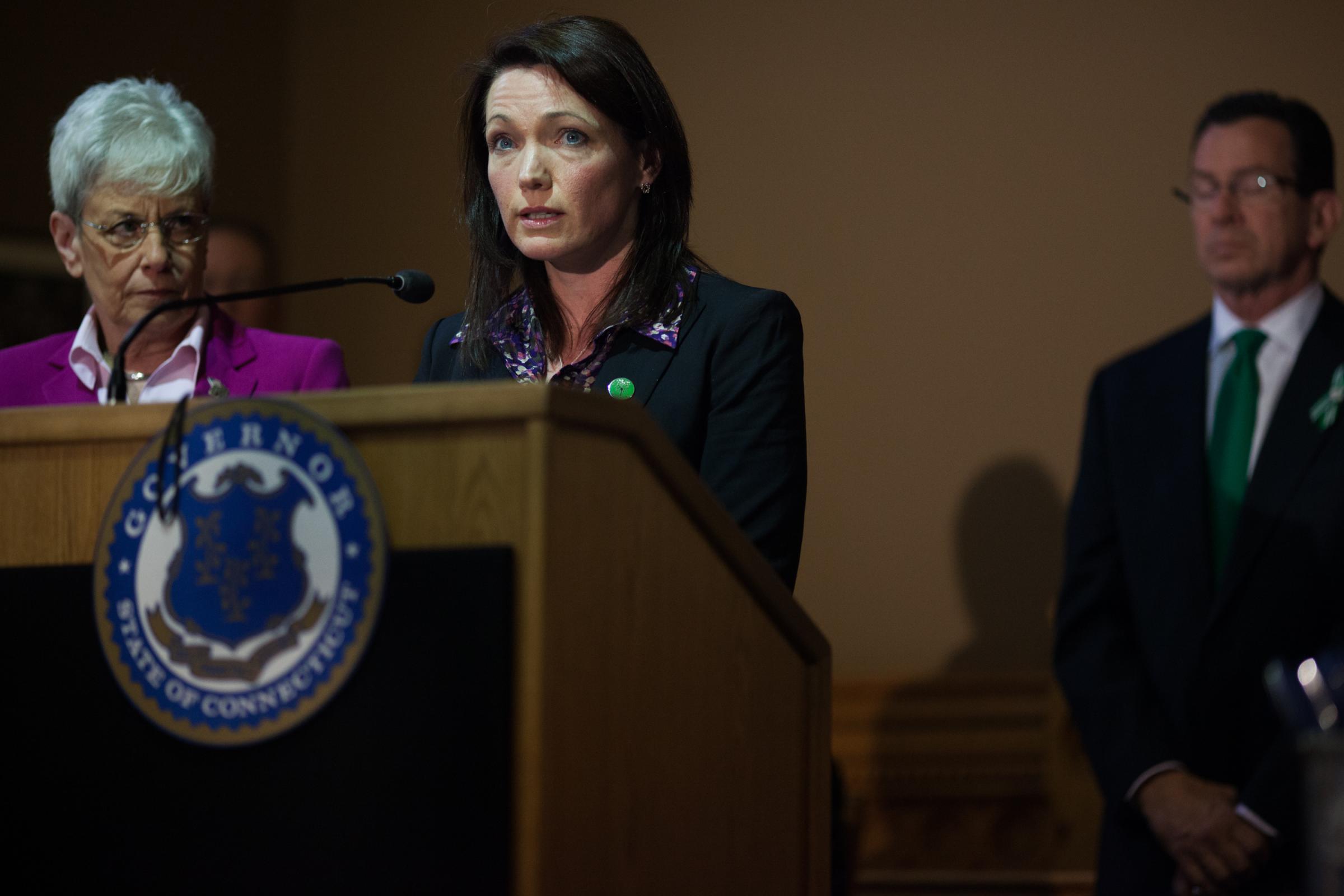

“You feel like your heart is bleeding in every new shooting,” says Nicole Hockley, whose 6-year-old son Dylan was killed in the 2012 shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Connecticut.

After this weekend’s deadly rampages, Hockley says she felt rage at the government’s “inaction” to combat gun violence and deep anguish for the families of the dead in Texas and Ohio whose lives will never be the same. “This is going to be a very long, lifetime process of never even really healing,” she says, “but just putting a scar over the wounds in your heart.”

In the months after her son was killed, out of routine, Hockley still called Dylan to dinner, still looked in her car’s rear view mirror to see his face in the car seat and still reached for his hand when she crossed the street. “These things become part of your daily life,” she says, “and suddenly there’s only space where that person once was.”

For Aryam Guerrero, no words could have consoled her after her 22-year-old brother Juan Ramon Guerrero was shot dead at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando in 2016. She was hopeful her brother was still alive when she and her family entered the hospital looking for him. Then she saw a sheet of paper with names of victims, including her brother’s. An FBI representative and hospital officials later broke the news to the family, prompting her mother to scream out.

“There’s nothing that anybody could have said that made anything make sense or make me feel better at all,” she says. The 27-year-old used to sob after hearing of new mass shootings, but because there were so many after Pulse, she became numb to them.

“It doesn’t get better. You have no choice but to live with it,” she says. “I just live my life as if I could die in the next 30 minutes.”

While the pain of loss never goes away, Mauser says, it gets easier with time. There’s no playbook or right way to handle grief, but Hockley, Mauser and Guerrero say it’s important to take time to mourn, talk through the pain and be surrounded by loved ones. “You need to give time to yourself to grieve and gather yourself and figure out what the hell just happened,” Mauser says. “If possible, talk to someone who has actually been there. There’s more of us now, unfortunately.”

Mauser also suggests leaning into anger but not dwelling on the lives of the shooters or giving them the infamy they crave. “In a case like this, you need to be angry. Something terrible happened. Someone destroyed a human life,” he says. “But then you also have to go through healing.”

“It’s hard to look at this aspect of it so early on, but before long you have to say to yourself, ‘Would my loved one want me to be in perpetual grief?’ No, they wouldn’t,” Mauser adds. “So don’t let yourself be in perpetual grief.”

In December, seven years will have passed since the Sandy Hook shooting, meaning Hockley’s son Dylan will have been dead more years than he was alive. She remembers some moments of his death with “exquisite painful detail” and others she can’t remember at all.

Hockley’s life was transformed and her marriage fell apart after the shooting, but she’s turned some of her pain into action. Hockley has become a fierce advocate for gun reform, as has Mauser, who sometimes wears the shoes his son was killed in when he rallies for gun violence prevention.

“You find a way to survive,” Hockley says.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com