They are both Democrats: Joe Biden, the 76-year-old former Vice President, and Ilhan Omar, the 36-year-old freshman Congresswoman. An old white man, with blind spots on race and gender and a penchant for bipartisanship; a young Somali-American Muslim who sees compromise as complicity. To Biden, Donald Trump is an aberration; to Omar, he is a symptom of a deeper rot. One argues for a return to normality, while the other insists: Your normal has always been my oppression.

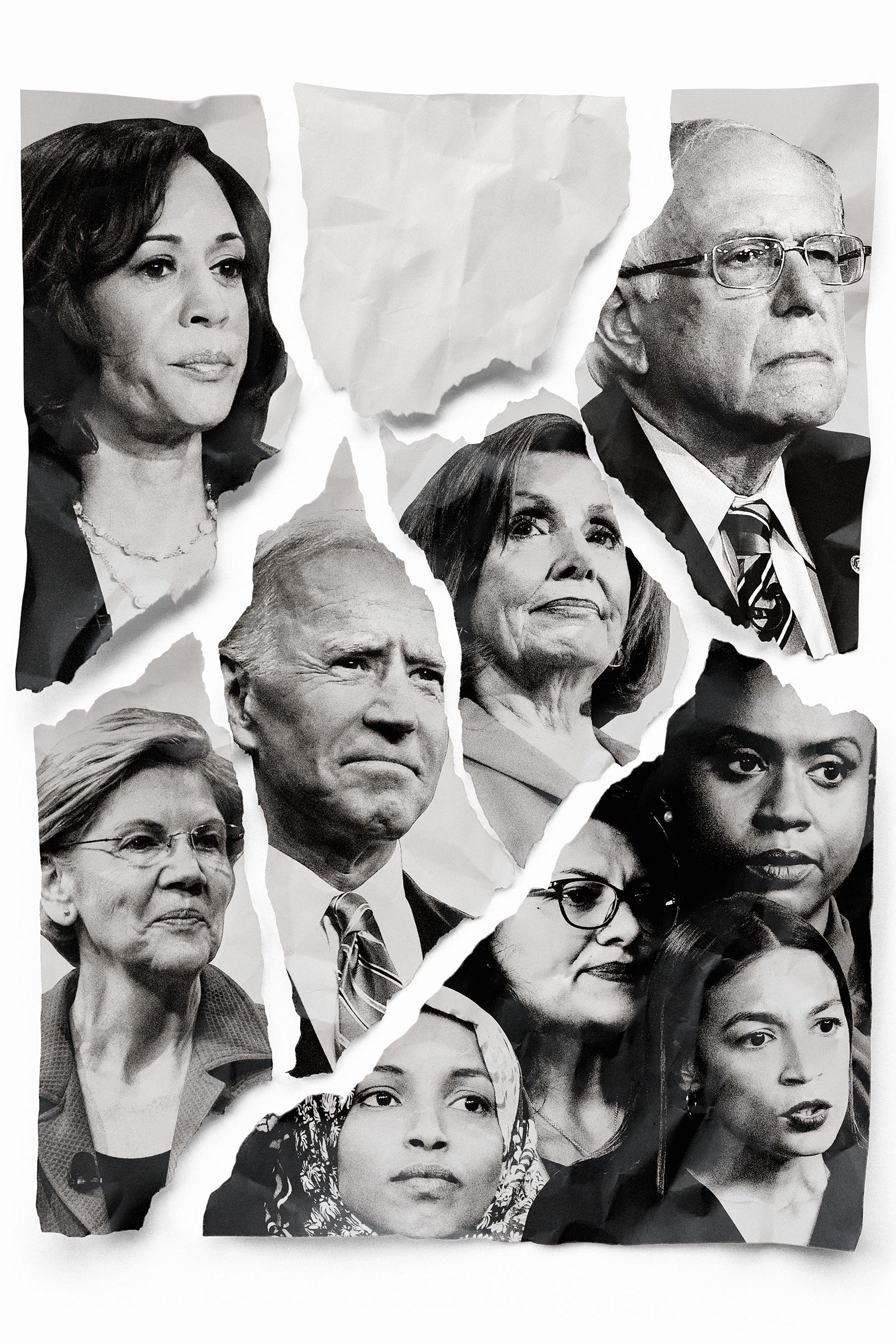

How to fit those two visions into one party is the question tying the Democrats in knots. What policies will the party champion? Which voters will it court? How will it speak to an angry and divided nation? While intraparty tussles are perennial in politics, this one comes against a unique backdrop: an unpopular, mendacious, norm-trampling President. As Democrats grilled Robert Mueller, the former special counsel, on July 24, their sense of urgency was evident.

The one thing Democrats agree on is that Trump needs to go, but even on the question of how to oust him, they are split. Ninety-five of the party’s 235 House Representatives recently voted to begin impeachment proceedings, a measure nearly a dozen of the major Democratic presidential candidates support. The party’s leadership continues to insist that defeating the President in 2020 is the better path. Half the party seems furious at Speaker Nancy Pelosi for not attacking Trump more forcefully, while the other is petrified they’re losing the American mainstream, validating Trump’s “witch hunt” accusations with investigations into Russian election interference that most voters see as irrelevant to their daily lives.

These divisions have come into focus in recent weeks. Two parallel conflicts–the fight among congressional Democrats, and debates among the 2020 candidates–have played out along similar lines, revealing deep fissures on policy, tactics and identity. A consistent majority of voters disapprove of the President’s performance, do not want him re-elected and dislike his policies and character. Even Trump’s allies admit his re-election hopes rest on his ability to make the alternative even more distasteful.

But for an opposition party, it’s never as simple as pointing out the failures of those in power. As desperate as Democrats are to defeat Trump, voters demand an alternative vision. “You will not win an election telling everybody how bad Donald Trump is,” former Senate majority leader Harry Reid tells TIME. “They have to run on what they’re going to do.”

The Democrats’ crossroads is also America’s. As Trump leans into themes of division, with racist appeals, detention camps for migrants and an exclusionary vision of national identity, the 2020 election is shaping up as a referendum on what the country’s citizens want it to become. This is not who we are as a nation, Trump’s opponents are fond of saying. But if not, what should we be instead?

“That little girl was me.” With this five-word statement at the Democrats’ June 27 debate in Miami, Senator Kamala Harris did not just strike a blow against Biden. She showed where the party’s most sensitive sore spots lie.

Harris explained that she had been bused to her Berkeley, Calif., public school as part of an integration plan; Biden, as a Delaware Senator, had worked to stop the federal government from forcing busing on school districts that resisted integration. On the campaign trail this year, Biden had boasted about being able to work with political opponents, citing his chumminess with Senators who were racists and segregationists. “It was hurtful,” Harris said, “to hear you talk about the reputations of two United States Senators who built their reputations and career on the segregation of race in this country.”

It was a powerful appeal, drawn from the personal experience of a woman of color whose life’s course was altered by the public-policy choices made in the halls of power. What was exposed wasn’t so much a real policy difference–after the debate, Harris took essentially the same position as Biden against mandatory busing in today’s still segregated schools–but a dispute about perspective. Biden, clearly ruffled, became defensive and eventually gave up, cutting himself off midsentence: “My time is up.” Biden remains the front runner, but the line had the ring of a campaign epitaph.

Presidential primaries are always the battleground for political parties’ competing factions, and some of the debates Democrats are enmeshed in now are ones they’ve been having for decades. Swing to the left, or tack to the middle? Galvanize the base, or cultivate the center? Tear down the system, or work to improve it? These familiar questions are now shadowed by the specter of Trump and his movement. If Americans are to reject Trumpist nationalism and white identity politics, what’s their alternative?

With two dozen presidential candidates and the race only just begun, the majority of Democratic voters say they are undecided. But a top tier of five candidates has emerged as the focus of voters’ attention: Biden, Senator Bernie Sanders, Senator Elizabeth Warren, Harris and South Bend, Ind., Mayor Pete Buttigieg. At the moment, it is Warren and Harris who appear on an upward trajectory, while the three male candidates trend downward.

Biden’s pitch to voters is moderation, electability and a callback to the halcyon days of the Obama Administration. Sanders seeks to expand the fiery leftist movement he built in 2016. Warren has staked her campaign on wonkishness and economic populism, while Harris paints herself as a crusader for justice. Buttigieg offers a combination of generational change and executive experience. To imagine each of them in the White House is to conjure five very different hypothetical presidencies come January 2021.

On Capitol Hill, the party has been spread along a similar axis of race, power, perspective and privilege. To address the humanitarian crisis on the southern border, Pelosi pushed a compromise bill this summer that sought to fund migrant detention while protecting the rights of asylum seekers. She was opposed by members of the so-called Squad–a quartet of outspoken freshman Representatives who have become champions of the party’s rising left wing: Omar, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York, Ayanna Pressley of Massachusetts and Rashida Tlaib of Michigan. All women of color, all 45 or under, all adept with a Twitter zinger and prone to inflammatory statements, they seek to build a movement and shake up the party–a markedly different theory of change from Pelosi’s dogged insistence on vote counting and the art of the possible.

The inevitable squabble ensued, complete with Twitter clapbacks and accusations of racism. Naturally, Trump–not content to let Democrats tear one another apart on their own–waded into the fray. He singled out the four women, implied that their American citizenship was not equal to that of others and declared that the Squad should “go back” to the countries of their ancestors rather than criticize.

The ugly sight of a President luxuriating in “send her back” chants laid down a marker for 2020. As much as traditional Republicans might like the President to campaign on a healthy economy, a tax cut that put more money in the pocket of two-thirds of Americans and a slate of new conservative federal judges, Trump plans instead to plunge even further into fear and division. And as much as Democrats might like to talk about health care, climate change and the minimum wage, their candidate will inevitably be dragged into his sucking morass of conspiracy mongering and tribalism.

For a moment, the controversy unified the bickering House Democrats, who passed a resolution condemning Trump’s comments. But behind the scenes, Democrats’ reactions to the spectacle were a test for the electoral theories of their feuding factions. Progressives (and many Republicans) argued that Trump was only making himself more toxic to swing voters. But some in the Democratic establishment fretted that Trump’s repellent statements were a political masterstroke, elevating four fringe figures as the face of the party.

There’s a reason for these fears: the Squad represents neither the Democratic majority in the House nor the Democratic mainstream. The party’s rank and file is older, more moderate and more numerous than its online-activist faction. But it’s the latter that has driven the conversation during the first phase of the primary. Candidates have voiced support for eliminating private health insurance, decriminalizing unauthorized border crossing, and providing health care for undocumented immigrants and reparations for slavery, none of which is popular with the general electorate. “The vast majority of presidential candidates are hopping on the bandwagon being presented by these four people,” says a senior Democratic congressional aide. “It just doesn’t make logical sense.”

Democrats’ success in the 2018 midterms was powered largely by moderate candidates in reddish suburban districts, where college-educated white women, in particular, swung against Trump’s brand of politics. But liberals say playing Trump’s game is the real electoral poison. “Why not be bold and brave? People want change,” says Karine Jean-Pierre of MoveOn, a left-wing group that endorsed Sanders in 2016. “Trump is not a genius. He’s just a racist. In 2018, he doubled down on immigration and the caravan, and suburban moms said, ‘No, we don’t like seeing babies in cages, we don’t like the Twitter wars, stop it.’ He was doubling down on hate, and the Democrats were talking about who we are as a country. We have got to make this election a referendum on Donald Trump.”

Trump has other plans. “He knows something that a lot of people in his universe know: if he makes this election about a choice, that bad guy … vs. Donald Trump, that he can win,” says former Democratic Senator Heidi Heitkamp, who is now running a group aimed at making inroads among rural voters to deny Trump a second term.

Only a big, diverse party could contain pols as divergent as Biden and Omar. And so the Democrats’ challenges are also an opportunity. This nasty, brutish chapter of American politics has voters hungering for stable leadership, a unifying vision, a path out of the darkness. From the ashes of Trumpism, the Democrats have a chance to build a new American creed–if only they can figure out what it is.

With reporting by Alana Abramson and Philip Elliott

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Molly Ball at molly.ball@time.com