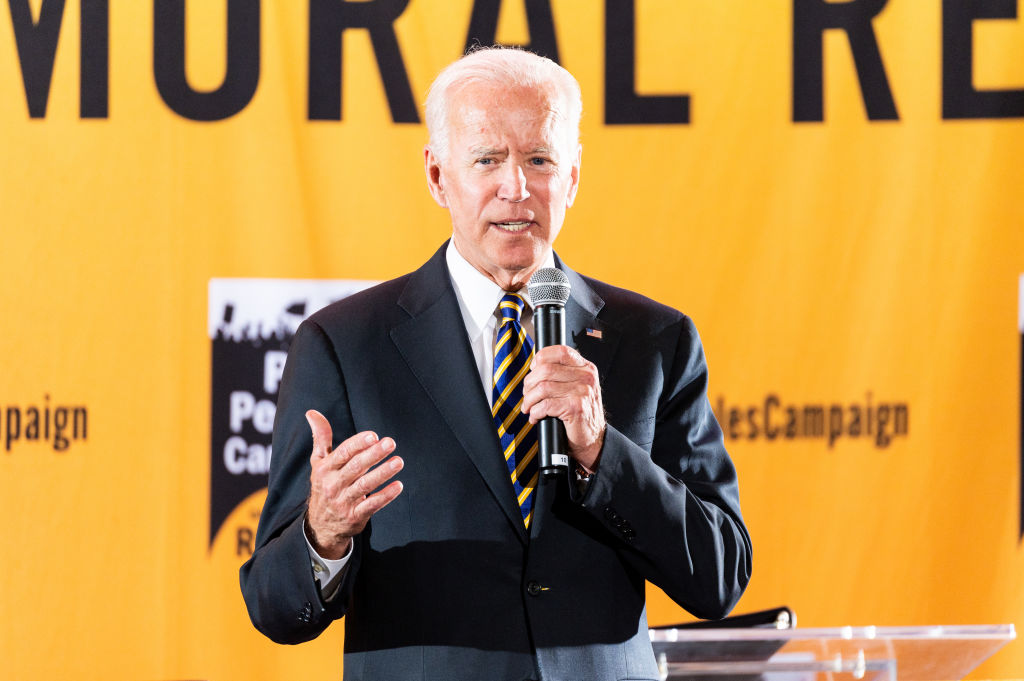

The vinegar in the slaw will hardly be the most acrid item on Joe Biden’s plate as he arrives at Rep. Jim Clyburn’s legendary fish fry.

The former Vice President had largely lucked out with news that Iran had shot down an American drone largely bumping from the headlines the Democratic frontrunner’s ill-advised comments about how he worked well with a segregationist senator. Biden has, to this point, refused to back down from those comments even as his rivals criticized him.

Still, Biden advisers warn, things between now and the July 4 holiday stand to be perilous for the campaign. On Friday, Biden is set to join most of his Democratic rivals at Clyburn’s fish fry, which will have a large African-American contingent that will want to know why, exactly, Biden, unprovoked, invoked the name of strident segregationist Sen. Jim Eastland during a New York fundraiser on Tuesday.

On Saturday, Biden will appear at a forum organized by Planned Parenthood Action Fund, where Biden’s long defense — since abandoned — of a prohibition against using federal Medicaid funds from being used to provide abortion services will be on trial. Then, next week brings back-to-back nights of debates where he’ll be the top target, even when he’s not on stage.

In other words, welcome to the Biden Pile-On.

“If anyone else wants the frontrunner role for a while,” darkly jokes a top Biden hand, “feel free to borrow it.”

Since Biden first invoked Eastland, there’s been a low-grade anxiety inside Biden’s orbit. Some advisers sought to minimize it, saying Biden was simply telling war stories from a half-century ago. Others thought Biden had done lasting damage to his relationship with African-American voters. Biden’s campaign eventually distributed a series of talking points to staff and outside advisers who were fielding calls from reporters and donors. Among them, Biden reached across ideological lines to get things done and, more recently, had served as the Vice President to the nation’s first black President, Barack Obama.

Biden’s campaign has seemed at time to be struggling to find its sea legs. Biden seemed to let the cat out of the bag that he was running during a March 12 union meeting and then a few days later, on March 16, did it again in a meeting with Delaware Democrats. He finally began his campaign with an online video on April 25, although there were mixed signals coming from his advisers about what would follow. He ended up making his first public campaign stop on April 29, with a relaunch of sorts on May 18.

Still, he’s cleared the tests his early naysayers flagged. He’s building a competent political machine and on Thursday announced 11 current or former South Carolina mayors were joining the campaign. Fundraising, always a worry for Biden and his longtime advisers, has proven strong. Online outreach, which he was seen as starting at a disadvantage, has been gangbusters. Early worries about his overly physical approach with strangers at rallies have largely faded.

Instead, they’ve been replaced with new challenges. For Biden, who has had his eyes on the White House since at least the 1980s, the actual act of campaigning has been tricky. He released an environmental plan on June 4 that omitted notes that parts of it came from others. (Staffers were to blame, aides said.) He remains an unscriptable pol who has confidence in his abilities and sincerity and isn’t one to anticipate how they will be interpreted.

Which speaks to Biden’s current predicament. On Tuesday evening, Biden told a crowded second-floor reception room at New York’s Carlyle Hotel that he remembers a time when “we got things done” in the Senate by working across party lines. The Upper East Side audience featured the likes of former Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin, Obama Administration car czar Steve Rattner and former Hillary Clinton adviser Lisa Caputo — political pros who got the gist of Biden’s push.

Then, unprompted, Biden invoked Eastland, one of the Senate’s unapologetic segregationists. While he did not praise Eastland, a Democrat from another era, he also didn’t condemn Eastland’s conduct in being the voice of the white South during the Civil Rights Movement, either.

Immediately, Biden critics and civil rights activists noted the blind spot. While Biden was preaching comity, his rivals saw, at best, a racial insensitivity in citing a man who led the opposition against the nomination of Thurgood Marshall to become the first African-American Supreme Court justice.

By Wednesday, some of Biden’s rivals were calling for an apology. “Vice President Biden’s relationships with proud segregationists are not the model for how we make America a safer and more inclusive place for black people, and for everyone,” Sen. Cory Booker said in a statement.

Speaking to reporters at the Capitol, Sen. Kamala Harris said: “To coddle the reputations of segregationists — of people, who if they had their way, I would literally not be standing here as a member of the United States Senate — is — I think, it’s just misinformed, and it’s wrong.” New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio joined in asking for an apology from Biden: “Eastland thought my multiracial family should be illegal.”

Sen. Bernie Sanders, speaking to MSNBC, kept picking the scab on Thursday. “I don’t think you have to be touting personal relations that are very brutal segregationists,” he said.

Biden was privately furious. He sensed that his rivals were not affording him sufficient respect and did not understand how Washington worked when he first arrived as a Senator in 1973. The Democratic Party has changed much since the South was represented by Dixiecrats who were hardly embracing the Civil Rights Movement. Because some of the candidates hadn’t even been born yet — Pete Buttigieg, Eric Swalwell and Tulsi Gabbard were born in the 1980s — they are largely immune to criticism of votes and politicking from that era.

The pressure was a preview of what Biden may face on Friday in South Carolina, where roughly two-thirds of the primary vote is expected to be African-American. Despite Biden’s long and deep ties to black voters, these new comments will at least be brought up. So, too, will his support for the 1994 crime bill that is now seen as unjust. At the same time, since he started running, there have been revelations that Biden long ago opposed busing as a way to desegregate schools in Delaware. And his handling of professor Anita Hill’s testimony during Clarence Thomas confirmation to the Supreme Court has been a sore spot.

Biden’s advisers knew the history was always going to be a challenge and that millennials, who are now the largest voting bloc in the country, have scant if any memory of Biden’s last bid in 2008, let alone the 1988 attempt. That means everything old is new again, according to one aide, so they’ve spent plenty of time since Biden left office in 2017 scouring the record to see what else Biden may have said or written. They think they have most if under control, or at least filed away for reference.

Instead, it’s the new material Biden provides his critics that has some Biden fans worried.

Biden for his part, insists he has nothing worth an apology. On the question of civility, he was genuinely gobsmacked by the reaction. Speaking to reporters outside a suburban Washington, D.C., fundraiser Wednesday night, Biden said that it was Booker who owed him an apology. “I’ve been involved in civil rights my whole career. Period. Period. Period,” he told reporters. (During his first run, in 1987, Biden was called out for saying he marched for civil rights. He did not.)

Biden’s life is expected to get no easier on Saturday, when he is appearing before an audience expected to be supporters of abortion rights — a position held by 78% Democratic women in the U.S., according to Pew Research Center surveys last year and speaking to the powerful role women play in picking the nominee.

Biden’s reversal on the so-called Hyde Amendment — which bars federal dollars from funding abortion — was long a sore point for voters who support abortion rights. His change was welcomed by those who back abortion rights, but there remain questions about what took him so long to switch. The campaign’s initial answers left some feeling uneasy, as if Biden were moving for political expediency. Some aides’ attempts to explain what persuaded Biden included a conversation with actress and activist Alyssa Milano. That suggestion left many amazed the former “Who’s the Boss?” child star could do what groups like Planned Parenthood have been trying since the 1970s.

Biden is not going to skate by on his answer.

Things then get messier. The campaigns start descending on Miami on Tuesday for debates scheduled for Wednesday and Thursday. Biden debates Thursday, which means everyone on night one will be focused on noting their differences with Biden — without him there to defend himself. (He or a rep from his team will, however, be allowed to visit the so-called “spin room” where they can try to push his campaign’s talking points. Trump in 2016 would sometimes do the spin himself.) Then, on the second night, all eyes will be on Biden on stage like this for the first time since 2012 and facing Democratic opponents for the first time since 2007.

Given how Biden has conducted himself so far, there are good odds he could stumble — especially if the fish fry and Planned Parenthood forum get under his skin.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Philip Elliott at philip.elliott@time.com