In her cinder block home in Venezuela’s second city of Maracaibo, 14-year-old Ana Bravo puts her hand to her mouth to signal her hunger. She is waiting for her mother to cook up a plate of yucca root, her only meal for that day.

Suffering from malnutrition and a learning disability, Bravo weighs just 44 pounds (20 kilograms) and stands below four feet, her arms thin as bone, her belly swollen. “We only eat at night, so that we don’t go to bed with nothing,” says her mother Glennis Delgado. In this embattled South American nation, they survive on charity and thin government handouts.

Advisory: Graphic content could be disturbing to some readers.

Their slum neighborhood has always been poor but since a severe economic crisis began around five years ago, it has slipped into desperation and malnutrition. It’s particularly difficult for those who already suffer from sickness or disability. In a nearby house, 28-year-old Miguel Blanco, who has a neurological condition, weighs just 66 pounds (30 kilos), his skin looking like it sticks to his bones, his muscles all but wasted away.

Neighbor Katherine Castilla fears for the survival of her two-month-old baby daughter, who was born prematurely and is failing to gain weight.

Venezuela remains far from famine, but food shortages are so persistent that the average resident lost 24 pounds in 2017, and malnutrition — a shortfall in calories and essential nutrients — is a growing concern, especially because it increases the risk of infectious disease. The latest report from Catholic charity Caritas finds that 23 percent of children under five in Venezuela suffer from malnutrition and another 34 percent are at risk.

For those who were already sick, the situation is dramatically worse. Essential medicines are, like food, have been difficult to find or afford for years now. Those who struggled for health in normal times have been most vulnerable to the country’s dysfunction. UNICEF says that 7 million Venezuelans, including 3.2 million children, are in need of assistance. “We are watching our people die,” says Carolina Leal, a community activist in the Maracaibo slum.

This humanitarian crisis has been at the heart of the political battle for control of Venezuela, including a failed uprising on April 30 that the Trump administration voiced support for. President Nicolás Maduro, the heir of socialist icon Hugo Chávez, is accused of chronic mismanagement. Since he took office in 2013, he has steered the nation that boasts the largest oil reserves on the planet into misery.

His opponent Juan Guaidó, who heads the national assembly and is recognized as the real interim president by more than 50 countries, including the United States, cites the hunger in his calls to soldiers and citizens to overturn Maduro.

Yet despite the depth of the crisis and President Trump’s backing for change, Maduro has been markedly resilient in clinging to power. Most of Venezuela’s military, especially the high brass, has stayed loyal to the socialist government while protests have been effectively put down with water cannons, rubber bullets and armored vehicles ploughing through demonstrators.

U.S. National Security Adviser John Bolton claimed on April 30 that key Venezuelan cabinet members had agreed to oust Maduro but as days went by they was no sign of these defections.

Attempts to bring in aid have been bogged down in these politics. In February, Guaidó tried to coordinate foreign convoys to ferry in food and medical supplies, which would also bolster his attempts to gain power. However, Venezuelan security forces and Chavista paramilitaries blocked them and maintained control of their own food handouts delivered in a scheme known as CLAP.

Maduro has long claimed the idea of a humanitarian crisis is manufactured by foreign forces as a prelude to regime change. “They try to justify a North American intervention and for humanitarian reasons, but they are looking for petroleum, the wealth of the county,” he said last year.

But while Trump has not ruled out military intervention in Venezuela, there are no solid signs he would commit to such a costly and problematic venture. Instead, he has bet on upping sanctions, shutting down Venezuela’s oil sales to the United States and cutting off the its Central Bank’s access to dollars.

Such sanctions, however, have a history of failing to topple governments in countries such as Cuba and Iraq, while punishing poor people the most. A report by the Center for Economic and Policy Research think tank blamed sanctions for exacerbating Venezuela’s poverty and said they could push humanitarian problems further over the edge. “The accelerating economic collapse that current sanctions have locked in assure further impacts on health, and premature deaths,” it says.

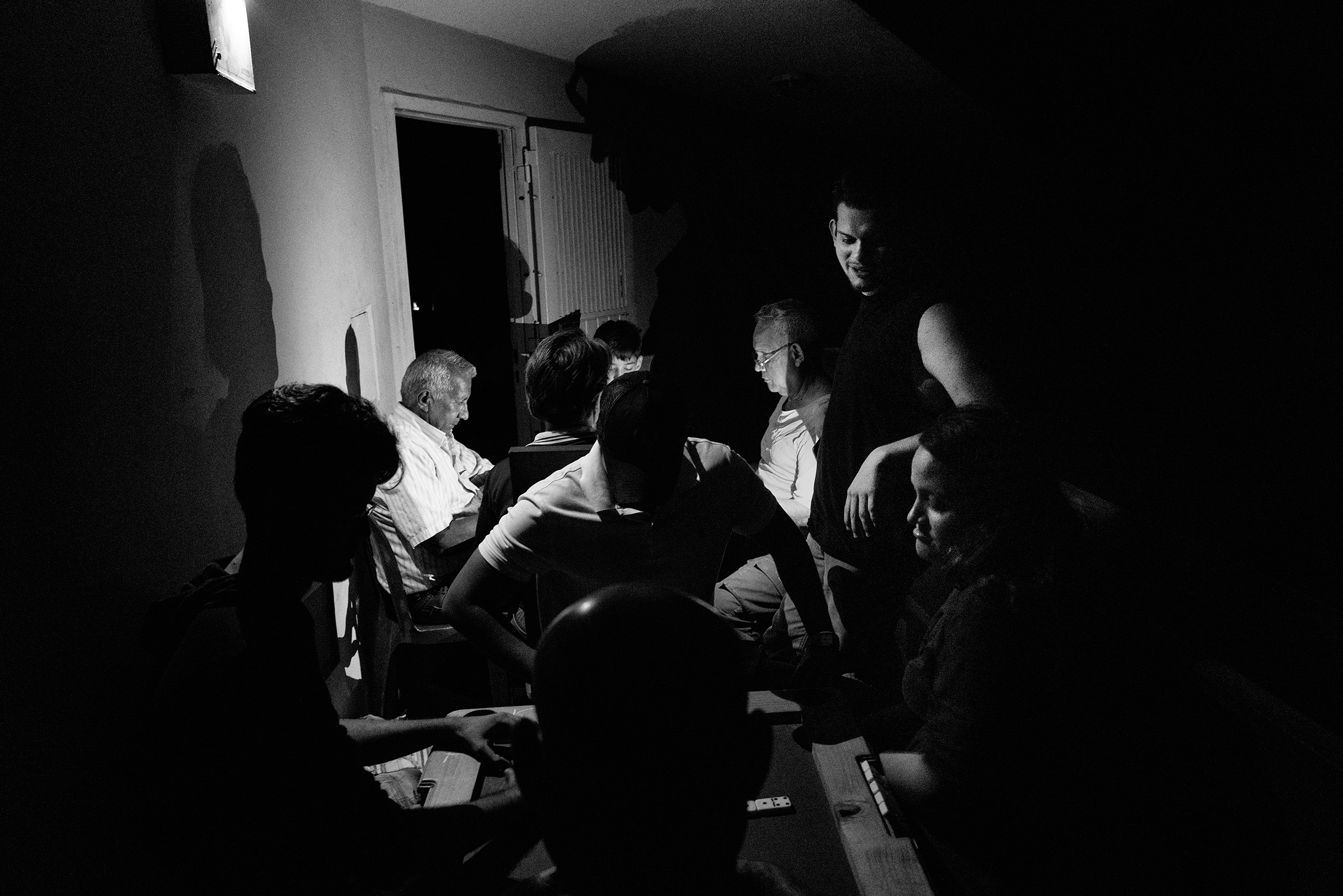

Those effects will be felt most harshly in slums like the ones in Maracaibo. The situation already feels like the aftermath of an earthquake, with a collapse in services, constant electricity black outs, sporadic running water. Garbage covers the streets, as people search through for scraps. Children only sporadically make it to school, if at all, and criminal gangs control the corners.

Gustavo Rincon, a pediatrician working in the neighborhood, says that even if the country recovers, the damage from malnutrition, including mental retardation and stunted growth, will haunt people for years to come. “This will cost a lot for the country to get over,” he says, “because the generational damage is irreversible.”

— With additional reporting by Ioan Grillo

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision