What it means to love my country, no matter how it feels about me

Love it or leave it. Have you heard someone say this? Or have you said it? Anyone who has heard these five words knows what it means, because it almost always refers to America. Anyone who has heard this sentence knows it is a loaded gun, pointed at them.

As for those who say this sentence, do you mean it with gentleness, with empathy, with sarcasm, with satire, with any kind of humor that is not ill humored? Or is the sentence always said with very clear menace?

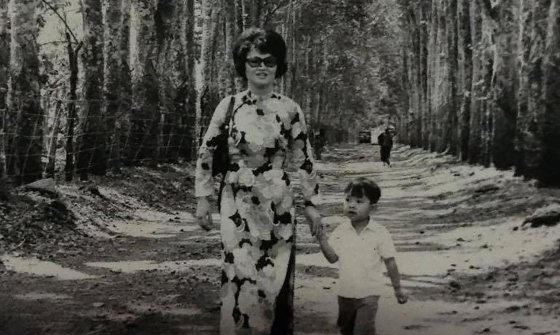

I ask out of genuine curiosity, because I have never said this sentence myself, in reference to any country or place. I have never said “love it or leave it” to my son, and I hope I never will, because that is not the kind of love I want to feel, for him or for my country, whichever country that might be.

The country in which I am writing these words is France, which is not my country but which colonized Vietnam, where I was born, for two-thirds of a century. French rule ended only 17 years before my birth. My parents and their parents never knew anything but French colonialism. Perhaps because of this history, part of me loves France, a love that is due, in some measure, to having been mentally colonized by France.

Aware of my colonization, I do not love France the way many Americans love France, the ones who dream of the Eiffel Tower, of sipping coffee at Les Deux Magots, of eating a fine meal in Provence. This is a romantic love, set to accordion music or Édith Piaf, which I feel only fleetingly. I cannot help but see colonialism’s legacies, visible throughout Paris if one wishes to see them: the people of African and Arab origins who are here because France was there in their countries of birth. Romanticizing their existence, oftentimes at the margins of French society, would be difficult, which is why Americans rarely talk about them as part of the fantasy of Paris.

The fantasy is tempting, especially because of my Vietnamese history. Most of the French of Vietnamese origins I know are content, even if they are aware of their colonized history. Why wouldn’t they be? A Moroccan friend in Paris points to the skin I share with these French of Vietnamese ancestry and says, “You are white here.” But I am not white in America, or not yet. I was made in America but born in Vietnam, and my origins are inseparable from three wars: the one the Vietnamese fought against the French; the one the Vietnamese fought against each other; and the one the U.S. fought in Vietnam.

Many Americans consider the war to be a noble, if possibly flawed, example of American good intentions. And while there is some truth to that, it was also simply a continuation of French colonization, a war that was racist and imperialist at its roots and in its practices. As such, this war was just one manifestation of a centuries-long expansion of the American empire that began from its own colonial birth and ran through the frontier, the American West, Mexico, Hawaii, Guam, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, Japan, Korea, Vietnam and now the Middle East.

One war might be a mistake. A long series of wars is a pattern. Indians were the original terrorists in the American imagination. The genocide committed against them by white settlers is Thanksgiving’s ugly side, not quite remembered but not really forgotten, even in France, where images of a half-naked Native American in a feathered headdress can also be found. Centuries later, the latent memory of genocide — or the celebration of conquest — would surface when American GIs called hostile Vietnamese territory “Indian country.” Now Muslims are the new gooks while terrorists are the new communists, since communists are no longer very threatening and every society needs an Other to define its boundaries and funnel its fears.

Many Americans do not like to hear these things. An American veteran of the war, an enlisted man, wrote me in rage after reading an essay of mine on the scars that Vietnamese refugees carried. Americans had sacrificed themselves for my country, my family, me, he said. I should be grateful. When I wrote him back and said he was the only one hurt by his rage, he wrote back with an even angrier letter. Another American veteran, a former officer, now a dentist and doctor, read my novel The Sympathizer and sent me a letter more measured in tone but with a message just as blunt. You seem to love the communists so much, he said. Why don’t you go back to Vietnam? And take your son with you.

I was weary and did not write back to him. I should have. I would have pointed out that he must not have finished my novel, since the last quarter indicts communism’s failures in Vietnam. Perhaps he never made it past being offended by the first quarter of the novel, which condemns America’s war in Vietnam. Perhaps he never made it to the middle of the novel, by which point I was also satirizing the failures of the government under which I was born, the Republic of Vietnam, the south.

I made such criticisms not because I hated all the countries that I have known but because I love them. My love for my countries is difficult because their histories, like those of all countries, are complicated. Every country believes in its own best self and from these visions has built beautiful cultures, France included. And yet every country is also soiled in the blood of conquest and violence, Vietnam included. If we love our countries, we owe it to them not just to flatter them but to tell the truth about them in all their beauty and their brutality, America included.

If I had written that letter, I would have asked this dentist and doctor why he had to threaten my son, who was born in America. His citizenship is natural, which is as good as the citizenship of the dentist, the doctor and the veteran. And yet even my son is told to love it or leave it. Is such a telling American? Yes. And no. “Love it or leave it” is completely American and yet un-American at the same time, just like me.

Unlike my son, I had to become naturalized. Did I love America at the time of my naturalization? It is hard to say, because I had never said “I love you” to anyone, my parents included, much less a country. But I still wanted to swear my oath of citizenship to America as an adolescent. At the same time, I wanted to keep my Vietnamese name. I had tried various American names on for size. All felt unnatural. Only the name my parents gave me felt natural, possibly because my father never ceased telling me, “You are 100% Vietnamese.”

By keeping my name, I could be made into an American but not forget that I was born in Vietnam. Paradoxically, I also believed that by keeping my name, I was making a commitment to America. Not the America of those who say “love it or leave it,” but to my America, to an America that I would force to say my name, rather than to an America that would force a name on me.

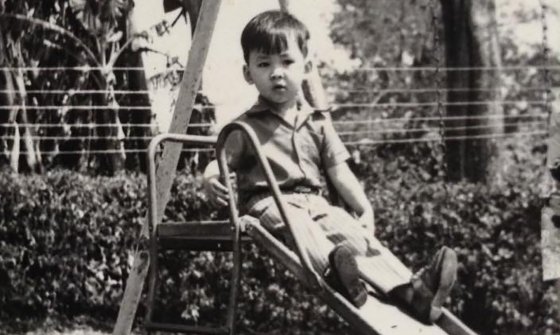

Naming my own son was then a challenge. I wanted an American name for him that expressed the complexities of our America. I chose Ellison, after the great writer Ralph Waldo Ellison, himself named after Ralph Waldo Emerson, the great philosopher. My son’s genealogy would be black and white, literary and philosophical, African American and American. This genealogy gestures at the greatness of America and the horror of it as well, the democracy as well as the slavery. Some Americans like to believe that the greatness has succeeded the horror, but to me, the greatness and the horror exist simultaneously, as they have from the very beginning of our American history and perhaps to its end. A name like Ellison compresses the beauty and the brutality of America into seven letters, a summation of despair and hope.

This is a heavy burden to lay on one’s son, although it is no heavier than the burden placed on me by my parents. My first name is that of the Vietnamese people, whose patriotic mythology says we have suffered for centuries to be independent and free. And yet today Vietnam, while being independent, is hardly free. I could never go back to Vietnam for good, because I could never be a writer there and say the things I say without being sent to prison.

So I choose the freedom of America, even at a time when “love it or leave it” is no longer just rhetorical. The current Administration is threatening even naturalized citizens with denaturalization and deportation. Perhaps it is not so far-fetched to imagine that one day someone like me, born in Vietnam, might be sent back to Vietnam, despite having made more out of myself than many native-born Americans. If so, I would not take my son with me. Vietnam is not his country. America is his country, and perhaps he will know for it a love that will be less complicated and more intuitive than mine.

He will also — I hope — know a father’s love that is less complicated than mine. I never said “I love you” when I was growing up because my parents never said “I love you” to me. That does not mean they did not love me. They loved me so much that they worked themselves to exhaustion in their new America. I hardly ever got to see them. When I did, they were too tired to be joyful. Still, no matter how weary they were, they always made dinner, even if dinner was often just boiled organ meat. I grew up on intestine, tongue, tripe, liver, gizzard and heart. But I was never hungry.

The memory of that visceral love, expressed in sacrifice, is in the marrow of my bones. A word or a tone can make me feel the deepness of that love, as happened to me when I overheard a conversation one day in my neighborhood drugstore in Los Angeles. The man next to me was Asian, not handsome, plainly dressed. He spoke southern Vietnamese on his cell phone. “Con oi, Ba day. Con an com chua?” He looked a little rough, perhaps working class. But when he spoke to his child in Vietnamese, his voice was very tender. What he said cannot be translated. It can only be felt.

Literally, he said, “Hello, child. This is your father. Have you eaten rice yet?” That means nothing in English, but in Vietnamese it means everything. “Con oi, Ba day. Con an com chua?” This is how hosts greet guests who come to the home, by asking them if they have eaten. This was how parents, who would never say “I love you,” told their children they loved them. I grew up with these customs, these emotions, these intimacies, and when I heard this man say this to his child, I almost cried. This is how I know that I am still Vietnamese, because my history is in my blood and my culture is my umbilical cord. Even if my Vietnamese is imperfect, which it is, I am still connected to Vietnam and to Vietnamese refugees worldwide.

And yet, when I was growing up, some Vietnamese Americans would tell me I was not really Vietnamese because I did not speak perfect Vietnamese. Such a statement is a cousin of “love it or leave it.” But there should be many ways of being Vietnamese, just as there are many ways of being French, many ways of being American. For me, as long as I feel Vietnamese, as long as Vietnamese things move me, I am still Vietnamese. That is how I feel the love of country for Vietnam, which is one of my countries, and that is how I feel my Vietnamese self.

In claiming that defiant Vietnamese self, one that disregards anyone else’s definition, I claim my American self too. Against all those who say “love it or leave it,” who offer only one way to be American, I insist on the America that allows me to be Vietnamese and is enriched by the love of others. So it is that every day I ask my son if he has eaten yet and every day I tell my son I love him. This is how love of country and love of family do not differ. I want to create a family where I will never say “love it or leave it” to my son, just as I want a country that will never say the same to anyone.

Most Americans will not feel what I feel when they hear the Vietnamese language, but they feel the love of country in their own ways. Perhaps they feel that deep, emotional love when they see the flag or hear the national anthem. I admit that those symbols mean little to me, because they divide as much as unify. Too many people, from the highest office in the land down, have used those symbols to essentially tell all Americans to love it or leave it.

Being immune to the flag and the anthem does not make me less American than those who love those symbols. Is it not more important that I love the substance behind those symbols rather than the symbols themselves? The principles. Democracy, equality, justice, hope, peace and especially freedom, the freedom to write and to think whatever I want, even if my freedoms and the beauty of those principles have all been nurtured by the blood of genocide, slavery, conquest, colonization, imperial war, forever war. All of that is America, our beautiful and brutal America.

I did not understand the contradiction that was our America during my youth in San Jose, Calif., in the 1970s and 1980s. Back then I only wanted to be American in the simplest way possible, partly in resistance against my father’s demand that I be 100% Vietnamese. My father felt that deep love for his country because he had lost it when we fled Vietnam as refugees in 1975. If my parents held on to their Vietnamese identity and culture fiercely, it was only because they wanted their country back, a sentiment that many Americans would surely understand.

Then the U.S. re-established relations with Vietnam in 1994, and my parents took the first opportunity to go home. They went twice, without me, to visit a country that was just emerging from postwar poverty and desperation. Whatever they saw in their homeland, it affected my father deeply. After the second trip, my parents never again returned to Vietnam. Instead, over the next Thanksgiving dinner, my father said, “We’re Americans now.”

At last, my father had claimed America. I should have been elated, and part of me was as we sat before our exotic meal of turkey, mashed potatoes and cranberry sauce, which my brother had bought from a supermarket because no one in my family knew how to cook these specialties that we ate only once a year. But if I also felt uneasy, it was because I could not help but wonder: Which America was it?