A perceptive, generous-spirited child draws on her imagination when she’s subjected to the cruelty of a boarding-school headmistress. A lone astronaut, cradled in a damaged space capsule and having lost any hope of returning to Earth, experiences a hallucination that saves her life. A young household servant, abandoned by the man who’s gotten her pregnant, miscarries—though his betrayal helps her define what family truly means to her. Loneliness, so universal it has virtually become trademarked the Human Condition, is everywhere in art, and in life: we tend to fetishize it, or at least dab it with a perfume of sentimentality. But Alfonso Cuarón, now more than 30 years into a wide-ranging career that spans pictures like the Frances Hodgson Burnett adaptation A Little Princess, the space reverie Gravity, and the memoir-as-film drama Roma, is more interested in subtle emotional textures, in gradations of feeling that are always specific to the character at hand yet also joltingly recognizable. And now he brings his big-screen, big-story gifts to a limited series, an adaptation of Renée Knight’s 2015 psychological thriller Disclaimer.

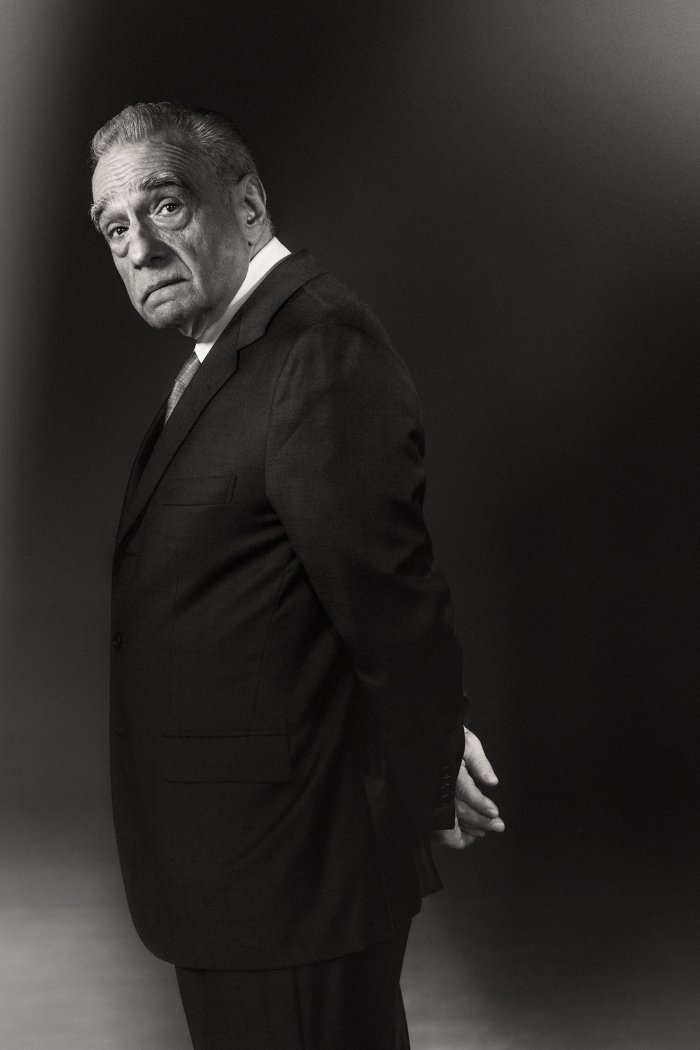

For Cuarón, who has a gift for making elegantly shaped pictures, structuring the seven-part series, streaming on Apple TV+, was a challenge but not necessarily a departure. “Some of the filmmakers I deeply admire have ventured into this [series] format,” he says in a Zoom call from his home in London. “Ingmar Bergman with Scenes From a Marriage, or David Lynch with Twin Peaks, or [Lars] von Trier with The Kingdom.” The point wasn’t to do something familiar, but to try something new. He had read Disclaimer, and wanted to adapt it, even before he made the 2018 multiple-Oscar-winning Roma. But it took him a while to realize that the story could be better told in a series rather than a movie. “I was challenged because I have never done anything that is overtly narrative. My films tend to be narratively very sparse. And I said, ‘Well, maybe that’s something I don’t know how to do.’” Why not try? Which, as he knows, is the best way to learn.

In Disclaimer, Cate Blanchett plays Catherine Ravenscroft, a successful London documentary filmmaker with a stable, devoted dullard of a husband, Robert (Sacha Baron Cohen), and a grown but directionless son, Nicholas (Kodi Smit-McPhee), who shows nothing but disdain for her. One day, Catherine receives a package, sent anonymously, containing a novel whose plot mirrors events from the early years of her marriage: She and Robert, along with Nicholas, then very young, have gone to Italy for holiday. After Robert is summoned back to London on business, Catherine, feeling lonely and neglected, flirts with a charming young student she meets on the beach, Louis Partridge’s Jonathan. Then, tragedy: Jonathan saves Nicholas from drowning, but he himself drowns in the process. Catherine leaves the scene, claiming not to have known the man who saved her son. He was just an anonymous hero, a kind of servant who had ensured the future of her safe, comfortable lifestyle.

Read More: Cate Blanchett’s Greatest Gift Is Her Humanity

But the young man had parents who, of course, felt his loss keenly. Jonathan’s mother Nancy Brigstocke (Lesley Manville) had given her son a camera before his trip. After his death, she developed his last roll of film, filled with steamy-arty shots of a lithe young blonde in lingerie, a woman so intent on seducing Jonathan that it seems she’d neglected her own child. Nancy was so undone by the loss of her boy that it seemed to hasten her death from cancer—but before she died, she left a novel behind, an imagined version of her son’s affair with this mystery blonde. Years after her death, her still grieving husband Stephen (Kevin Kline) finds the novel locked in a drawer and decides to publish it. The disclaimer on the novel’s opening page makes his intent clear: “Any resemblance to persons living or dead is not a coincidence.”

Knight’s novel is lots of things at once: a thriller, a riff on the idea of the unreliable narrator, a meditation on how easy it is, with all the digital means at our disposal, to cancel a career or, worse, ruin a life, simply because we think we know all the facts. Yet in some ways, Cuarón—who also adapted the script—has taken the themes of Knight’s book and intensified them. His take is elegant and suspenseful, but it’s also compassionate. Disclaimer is about, he says, the stories that we build out of our own lives, which we then present to others—to the people closest to us but also to society. “As humans, we’re trying to cope with many different things,” he says, “but mainly, probably, with an immense sense of loneliness.”

Our fears and insecurities influence the way we project ourselves in the world, and that can be harmful to ourselves or to the people we love. But the danger doesn’t stop there. It extends, Cuarón says, “in a macro way, in the way societies create their own narratives to hide things of the past.” We may convince ourselves of the truth of those stories, but that doesn’t make them accurate. “The history of humanity is recorded in narratives. But those narratives can also be a very powerful weapon to manipulate, because they’re hitting into the strong, deeply held beliefs of every single person,” he says. “It’s easy to say, ‘Oh, I was manipulated.’ Yeah, why? Because you already had those beliefs, even if they were dormant.”

Read More: The 100 Best Movies of the Past 10 Decades

Multiple characters in Disclaimer believe what they want to believe, easier than reckoning with reality. When Cuarón was young, he’d seen Bernard Queysanne’s 1974 The Man Who Sleeps, written, in the second person, by the experimental novelist Georges Perec. In structuring Disclaimer, Cuarón wanted to try telling the story in first-person, second-person, and third-person voices: Kline’s Stephen is the “I.” The people around Catherine—anyone who might be tempted to judge her—are the third-person observers. And Catherine’s story is told in the second person: she narrates her own arc, as if rendering judgment on her own behavior—accusing rather than defending herself, perhaps.

The use of the second person, Cuarón notes, is rare in film, and maybe not the sort of approach you could pull off with just any actor. But Blanchett, he says, was more than just the star of the series. Though he usually doesn’t write a script with an actor in mind, this time was different: “I’m writing, and I’m thinking of Cate.” He knew how fortunate he was when she said yes, and he considers her a creative partner on the project. She’d marked up her script à la Dostoyevsky’s manuscripts. “Have you seen those? How he wrote arrows moving up and down, and scratching parts out, and little things that only he understood? That was Cate’s script.” She asked questions that helped him shape the story. And she was the first person, he says, to see the initial cut. Cuarón says her feedback was invaluable. “That was Cate. Incredible! I’m so blessed and lucky.”

But then, luck comes to those who are open to it. And Cuarón’s MO is to welcome the collaborative gifts of people he trusts, like his longtime friend and creative partner Emmanuel Lubezki, who has shot most of his movies. It was Lubezki’s idea to bring on a second cinematographer, Bruno Delbonnel, whose credits include films as varied in style as Amélie and Inside Llewyn Davis. Lubezki—Cuarón, along with just about everyone else, calls him Chivo—was the one who’d suggested changing the look of the film according to the shifting points of view: there are flashback scenes requiring a softer look, while sequences set in the present might demand higher contrast or slightly crisper images. “It was beautiful,” Cuarón says, “to see the conversations between the two of them collaborating.”

Shooting with two cinematographers took a great deal of planning and coordination. But Cuarón is most aware of the demands he made on his actors—and how ably they met them. He had initially planned to write and direct just the pilot for Disclaimer. But once he started writing, he didn’t want to stop, and he agreed to direct the whole series. He decided to treat the project as one long film—which meant shooting more script pages each day, resulting in a much longer schedule. (The shoot ran from February 2022 to April 2023.) “Poor guys!” Cuarón says of his actors. “They had to be stuck with a character for more than one year.” Normally, they might do two or three films in that time, but they were committed to this project, and to these challenging characters, among them Blanchett’s Catherine, who becomes a pariah in her own family; Kline’s Stephen, motivated by a mingling of grief and a need for revenge; and Manville’s Nancy, whose vision of her lost son becomes a ghost she can’t shake. These are demanding roles, further complicated by the challenges of shooting under COVID-19 restrictions.

Read More: The 34 Most Anticipated TV Shows of Fall 2024

Cuarón is proud of all his actors, and he marvels at the fact that they stuck with him. “I’m so blessed with them,” he says, and by this point in the conversation, a theme has emerged. Cuarón may be one of our most graceful, inventive filmmakers, but even beyond that, every project he touches is marked by a distinct generosity of spirit. Blessings rarely flow in just one direction, and the more goodwill you put out there, the more you get in return.

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness