If you didn’t grow up with a well-worn copy of Sounds of Silence, Bookends, or Bridge Over Troubled Water among the LPs stacked near the family hi-fi, your parents or grandparents probably did. From the mid- to late 1960s, the sounds of Simon & Garfunkel were so ubiquitous you couldn’t escape them if you wanted to. Their songs, not overtly political, dealt with everyday things like friendship, impending breakups, the simple pleasures of spending a day at the zoo, and their opaline harmonies had a soothing, shimmering quality. Paul Simon and Art Garfunkel—who’d been friends and musical compatriots since their childhood in Queens—broke up, somewhat acrimoniously, in 1970; it took fans ages to recover. While Garfunkel pursued acting, Simon soldiered on as a singer-songwriter, and the numerous highs—and occasional lows—of his career form the arc of Alex Gibney’s perceptive and comprehensive two-part docuseries In Restless Dreams: The Music of Paul Simon. (The docuseries airs in two parts on MGM+, on March 17 and March 24.)

Gibney, known for docs like Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room and Taxi to the Dark Side, threads Simon’s past and present into a graceful whole. He spends time with Simon in the small, cozy studio adjacent to his Wimberley, Texas, home—a facility with the kind of luxe, cowboy-rustic quality that only lots of money can buy—as Simon, now 82, prepares his 15th solo album, Seven Psalms, released last May. After the Simon & Garfunkel breakup, Simon became hugely successful, with some bumps along the way. He took chances on projects that didn’t work—1980’s One Trick Pony, a movie in which he played a fictional version of himself, flopped, and his 1983 studio album Hearts and Bones, written and recorded around the time of his intensely brief marriage to Carrie Fisher, disappointed fans who’d been hoping for a Simon & Garfunkel reunion album. The two had reconciled in 1981 for a blowout concert in Central Park, though as the documentary makes clear, Simon still couldn’t get past his erstwhile partner’s annoying habits and perceived self-centeredness, which is why he decided to cut himself free once again.

Even so, in the context of such a vast and varied career, those small dips seem inconsequential. Gibney frames Simon’s past—beginning with charming black-and-white publicity photos of teenage Paul and Art taken around the time of their first, baby-step hit, “Hey Schoolgirl,” in 1957—with the realities of his present. His marriage to fellow singer-songwriter Edie Brickell appears to be one of ardent closeness. (Brickell tells a wonderful story about performing her hit “What I Am” on Saturday Night Live, in 1988, and botching the words as she catches sight of Simon standing near one of the monitors. Gibney illustrates the moment with a clip—we get to see the lightning bolt hit.) But as Simon writes and records Seven Psalms, circa 2021, he struggles with hearing loss, and he’s frank about how much this distresses him. He’s able to write with the help of small Bose speakers attached to his computer, but has trouble figuring out how to sing. He runs through a lyric in front of the mic and stops short after hitting a clunker: “I’ll have to grab that note another day.”

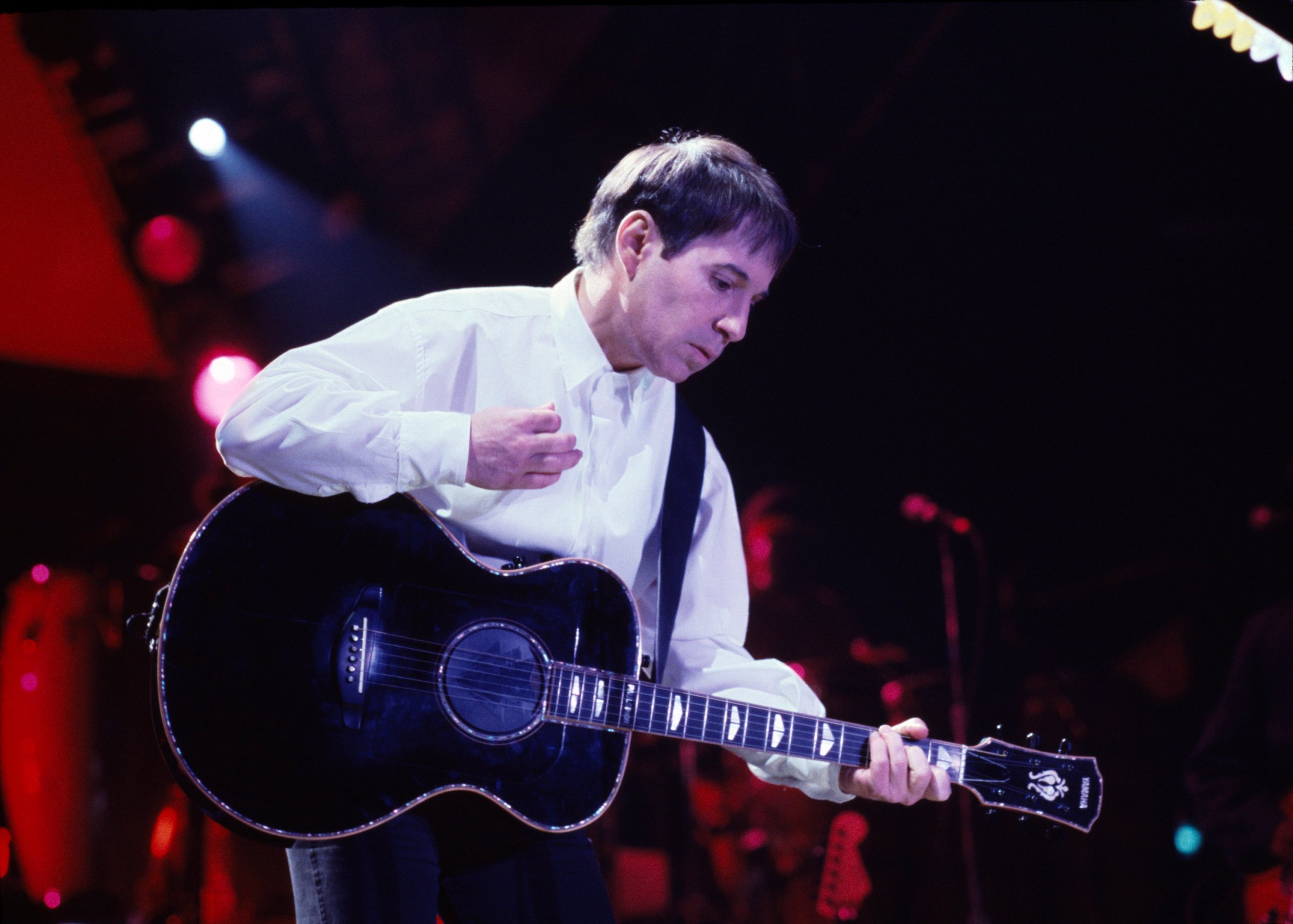

Mostly, though, In Restless Dreams rings with jubilance. Simon still revels in the mystery of where songs come from, and we also learn some tricks about how they become dazzling, finished artifacts. (The echoing drums featured on Simon & Garfunkel’s “The Boxer” were recorded, by ace engineer Roy Halee, near an elevator shaft.) Gibney includes choice clips of Simon appearing on talk shows in the 1970s, a thoughtful, elfin presence with a dry sense of humor. (At one point he says that he loves hearing his songs in an elevator, or, better yet, being hummed by a stranger on the street.) Look for his sly smile as he sits side-by-side with George Harrison, performing “Here Comes the Sun” on Saturday Night Live in 1976. Even for a big deal like Paul Simon, getting to perform with a Beatle is clearly a very big deal.

Best of all is the footage from the era of Simon’s 1986 Graceland, showing him talking and laughing with musicians in Johannesburg—though he’s also listening to them intently, and learning from them. The album was controversial in its era: Simon had broken the cultural boycott against South Africa, imposed as a response to apartheid, and he was also accused of cultural appropriation. But Gibney reframes that controversy by including vintage clips of exiled musicians Hugh Masekela and Miriam Makeba, both of whom toured with Simon after the album’s release. For these artists, unwelcome in their home country, the chance to perform with Simon and to bring their music to new and bigger audiences constituted a spiritual homecoming, at least. As Wynton Marsalis, one of Simon’s collaborators on Seven Psalms, puts it, his work represents “not the reduction of feeling, but the expansion of feeling.” That’s how a kid from Queens can reach out to the bigger world—and give it back to us, heard anew.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com