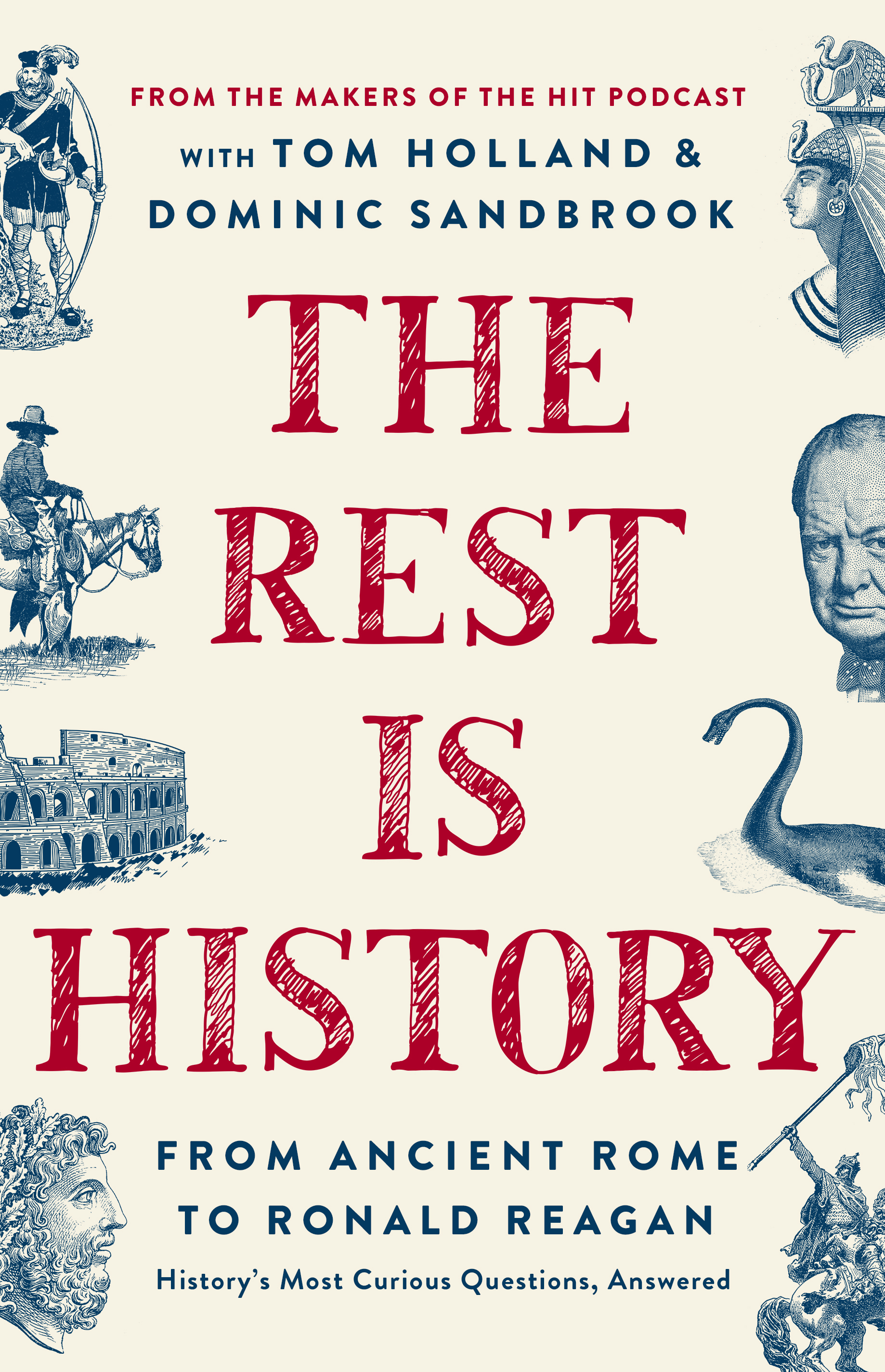

Since debuting in 2020, the hit podcast The Rest is History has broken down a range of topics in history, featuring everything from discussions on the American Revolution to lighthearted debate over whether President Richard Nixon is more like Roman emperors Caligula or Claudius. Over 535 episodes so far, each running roughly 50 minutes, historians Tom Holland and Dominic Sandbrook try to find the humor in history. But they also tackle serious topics; their latest series looks at the assassination of President John F. Kennedy and the many conspiracy theories surrounding that fateful day. On Dec. 5, the duo will release a book, also titled The Rest is History, which largely focuses on entertaining moments throughout history. There are several lists, like a ranking of history’s most famous mistresses. Pigeons get their own chapter. And because the podcasters first became friends while watching extended versions of Lord of the Rings together, they’ve included a letter that Tolkien wrote to his publisher addressing edits to his manuscript.

In a late-November video chat with TIME, Holland and Sandbrook talk about some of the funniest parts of the book and how they approach getting more young people to enjoy learning history. This conversation has been edited lightly and condensed for clarity.

What kind of problem with the way history is taught do you see your new book and podcast trying to fix?

DOMINIC SANDBROOK: There's a sense that history is some sort of hideous breakfast gruel that you are forced to eat in a Victorian workhouse because it will improve you. And we actually think history should be fun. If you don't make it enjoyable, if you don't relish in the characters, the stories, then you will never get kids interested in it.

Was there a specific episode of your podcast that catapulted it to viral fame?

TOM HOLLAND: We did an early one about the origins of the First World War. There is a story that the Kaiser attended a regatta at Cowes on the Isle of Wight, was laughed at by the British royal family for wearing the wrong shoes, and that his resulting sense of humiliation made war inevitable. We ran with this as a joke, paralleling the incredibly dark storyline of the world going to war—that definitely became viral. We still get people making jokes about how the wrong person wearing the wrong shoes might precipitate the Third World War.

What are some of the most popular episodes of the podcast?

HOLLAND: Our most popular episodes are, in the main, what you would expect—Nazis, Atlantis, Romans. One unexpected one was the Hundred Years’ War—I’ve no idea why that was so popular, except that it is a very thrilling story, featuring longbowmen, princes behaving badly, and lots of knights.

Your book has a list of the 10 most disastrous parties in history. What’s the most disastrous one, in your opinion?

SANDBROOK: This party [on Nov. 14, 1908], in which German general Dietrich von Hülsen-Haeseler. a big man with an enormous mustache, is wearing a ballerina’s tutu. He does a few pirouettes, and mid-pirouettes, he has a cardiac arrest and dies. [His staff] is trying to drag him out of the tutu and get him back into his Prussian uniform.

You also have a chapter on top dogs in history. How are dogs a lens for looking at history?

HOLLAND: Because they don't speak, people can project onto them. The reasons that people variously throughout history have loved dogs tells you quite a lot about them. So Hitler had the dog Blondie, a Teutonic wolf-like dog. It’s an embodiment of the ferocity of the primordial Aryan forests.

SANDBROOK: Hitler also had that dog in the trenches. When he was in World War I, he lost his dog, and he thinks it was taken by the British when he had to move down the line. This scar in Hitler's soul because of the loss of his dog was massive because Hitler was very sentimental about animals.

You even have a chapter on beavers! Why do people have beavers to thank for making Manhattan such a destination?

HOLLAND: Before the Europeans arrived, the whole of North America and particularly Canada, was absolutely teeming with beavers. Beaver pelts are very water resistant, and when the Europeans came, they discovered that they were absolutely perfect for making hats. On the back of this [discovery], enormous fortunes were made. It was appalling news for the beaver. It was tremendous news if you were a gentleman who wanted to keep his head warm and dry in the rain. And Manhattan became a center for the beaver trapping trade. In a way, beavers were one of the earliest [examples] of the process of environmental disruption that accompanied the rise of capitalism in America, and indeed, Canada.

How will future historians write about the present?

SANDBROOK: [It’s] a period of great anxiety, one of enormous cultural and technological opportunity, in which lots of people are making a lot of money, but one in which all kinds of anxieties and paranoias are flourishing. A lot of old certainties have been swept away, but we're not really clear what's coming. The present is an age of religious enthusiasm—not strictly speaking organized churches and things as it would have been in the past—but [defined by] cults of superstitions, revivalist movements of the political kind.

What overall theme do you want readers to take away from the book?

SANDBROOK: By and large if you're a curious person, then the past is a source of endless entertainment—stories, characters, remarkable things happening, unanticipated consequences. Ultimately, the single thing that people should take away not just from our book or from our podcast, but from studying history more generally, is that learning about other people is part of being human. And there's nothing more fun than that.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com