Though the new movie Jojo Rabbit opens in U.S. theaters on Friday, it has already acquired a divided reputation. It won the People’s Choice Award at the Toronto International Film Festival and has drawn strong Oscar buzz, but its satirical approach to a story of Nazi Germany has also turned some critics off.

Perhaps that’s no surprise given the way the film’s plot mixes two combustible ingredients: the Holocaust and childhood. The adaptation of the 2004 novel Caging Skies is about Jojo (played by Roman Griffin Davis), a 10-year-old member of a Nazi organization for preteens called the Jungvolk, who realizes his mother (Scarlett Johansson) has been letting a Jewish girl named Elsa (Thomasin McKenzie) hide out in their home. Meanwhile, Jojo’s imaginary friend, played by director Taika Waititi, is Nazi dictator Adolf Hitler himself.

While these characters are fictional, Nazi youth groups like the one Jojo joins were very real. As in the movie, some members were fiercely dedicated to Hitler while others would fit Elsa’s description of Jojo, as “a 10-year-old kid who likes dressing up in a funny uniform and wants to be part of a club.”

And, even nearly a century after these groups were first established, the questions raised by their existence — about the role of children in the history of hate, and the way hate affects those children — remain powerfully relevant.

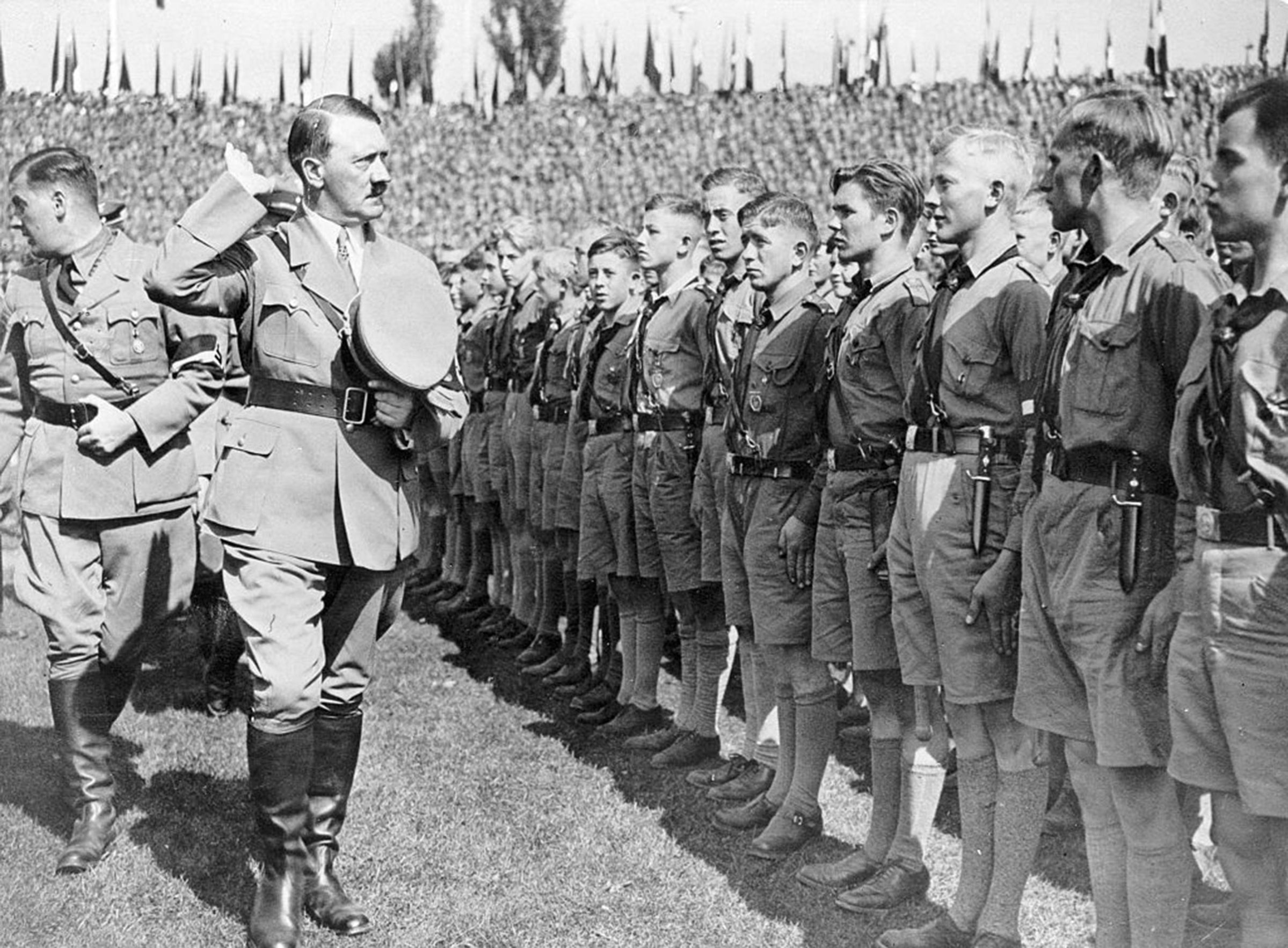

That children would be involved in the Nazi regime was clear from the beginning. As Adolf Hitler put it at the annual Nazi party rally in 1935, “He alone who owns the youth gains the future.” (This quote has also been paraphrased as “Whoever has the youth has the future.”)

The development of youth organizations meant to groom the future leaders of his Nazi Party dated back to the establishment of the party in the early 1920s. Membership was voluntary until 1936, when all boys and girls in Nazi Germany were required by law to join a Nazi youth group. All boys over 10 years old joined the Jungvolk (meaning “Young People”), and then graduated to the Hitler Youth when they turned 14. Likewise, girls joined the Jungmädel (“Young Girls”) and then graduated to Bund Deutscher Mädel (the “League of German Girls” or BDM for short).

When Adolf Hitler assumed power in 1933, about 100,000 girls and boys were members of all the organizations combined. By the end of 1933, there were over 2 million, and over 5.4 million by the end of 1936. Youths who were discovered not to have joined could be sent to “re-education” camps or their parents were fined and imprisoned.

“He had to have recruits, people who would take over as grown-ups and continue the ideology of the Third Reich,” says historian Michael Kater, author of Hitler Youth and Culture in Nazi Germany.

“History is fed to boys as a story of the great German destiny,” TIME described in a July 1941 report on the inner workings of youth organizations in Nazi Germany. “Mathematics is taught in terms of bullet trajectories, range-finding, sextant-reading, aerodynamics. As members of the Hitler Youth, the little leader-geniuses are searched for the qualities every German warrior must have: punctuality, orderliness, reliability, subordination, gregariousness, adaptability, diligence, will power, aggressiveness, acute sensory perception, practical talents. Each boy’s record is tabulated, analyzed and filed away, so that his complete case history of character development will be available for the future use of Army psychologists.”

But while the adults involved knew that they were grooming a new generation of Nazis, many of the children would later recall the period in more innocent terms, even as their fun was in the service of hateful indoctrination. A July 8, 1935, TIME article reported that 9 million “apple-cheeked, wondering children” had participated in Summer Solstice Festivals through the Hitler Youth, at which they were told by Hermann Göring that Adolf Hitler was performing God’s miracles. Later, students in Germany were required to read material like the 1938 essay Comradeship, by Hans Wolf, which presented camping with the Hitler Youth as a time of “wonderfully thrilling stories” and communing with nature.

In his 1985 memoir, another former member, Alfons Heck, described the program in its pre-war days as similar to Boy Scouts. He fondly recalled activities like the “test of courage” in which members were required to jump from a high diving board. “There were some stinging belly flops,” he wrote, “but the pain was worth it when our Fähnleinführer, the 15-year-old leader of Fähnlein (literally “little flag”), a company-like unit of about 160 boys, handed us the coveted dagger with its inscription Blood and Honor. From that moment on we were fully accepted.”

Heck also reveled in the chance to get out of the house and socialize with people his own age. As he wrote, “Far from being forced to enter the ranks of the Jungvolk, I could barely contain my impatience and was, in fact, accepted before I was quite 10. It seemed like an exciting life, free from parental supervision, filled with ‘duties’ that seemed sheer pleasure.”

Meanwhile, girls collected tin foil and warm clothes for soldiers, and received lessons on farming, cooking, cleaning, singing, swimming, gymnastics and running — activities that might sound pleasant enough, but were designed to keep their bodies and their homes in good physical shape so that they could attract a mate and raise children in the Nazi ideology. For some, participation in the Hitler Youth was also seen as a leg up in society, Kater adds, as children from all economic backgrounds wore the same uniforms.

Some members of Hitler Youth organizations who went on to fame after World War II have cited these more innocent attractions as central to their memories of participation in such a group, or said they only joined because they had to.

For example, the artist Gerhard Richter told TIME in 2012 that he was in a Hitler Youth group “just like the Cub Scouts” in a village on the border of Czechoslovakia, describing it as “not very serious” compared to other groups, and admitting, “I was proud of this nice uniform I had, with this belt.” Others have said that mandatory participation meant that being in such a group didn’t necessarily say anything about a person’s beliefs. When Pope Benedict XVI’s past with the Hitler Youth made headlines in 2005, for example, he said he went to the meetings in order to receive a tuition discount he needed for school, and his brother said their father would still gather them to listen to Allied radio broadcasts.

But, especially after World War II officially began in 1939, being a member of a Hitler Youth organization was not about seemingly innocent camping trips and the bonds of friendship.

Members of Hitler Youth groups aided storm troopers in atrocities carried out by the Nazi regime, according to Kater — from ordering Jewish people in Vienna to clean the pavement with toothbrushes or their own hands, to raiding synagogues and destroying sacred Hebrew scrolls and texts. Members of the girls’ groups served in administrative positions in Nazi offices, or as nurse’s aides, farm laborers or munitions-factory workers.

In a 1943 TIME article on life in Nazi Germany, one British Army chaplain who had been a prisoner of war gave the Gestapo and the Hitler Youth shared credit for the situation: “Hitler has made the youth and the youth are ruling Germany.”

Some members of these organizations were particularly infamous. The Auschwitz guard Irma Grese, who was notorious for setting a pack of attack dogs on her inmates, began that work as a teenage member of a youth organization. A British Army court sentenced her to death by hanging in the fall of 1945. In 1946, Baldur von Schirach, the first leader of the Hitler Youth, was convicted of war crimes in 1946, and sentenced to 20 years in prison.

Even the example of Günter Grass, the 1999 winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature who was often called Germany’s moral conscience, showed how membership in a youth organization could seamlessly lead to a more adult Nazi role, just as was intended. Grass made no secret of the fact that he joined the Jungvolk at 10 and the Hitler Youth at 14, and as he said in a 1970 TIME cover story, that he thought “right up to the end in 1945 that our war was the right war.” But he made the explosive revelation in 2006 that he had also served in the SS, the Nazi German police force — a belated disclosure that many saw as hypocritical.

At the same time, despite the mandatory nature of participation, the history of Nazi youth organizations does contain examples of resistance.

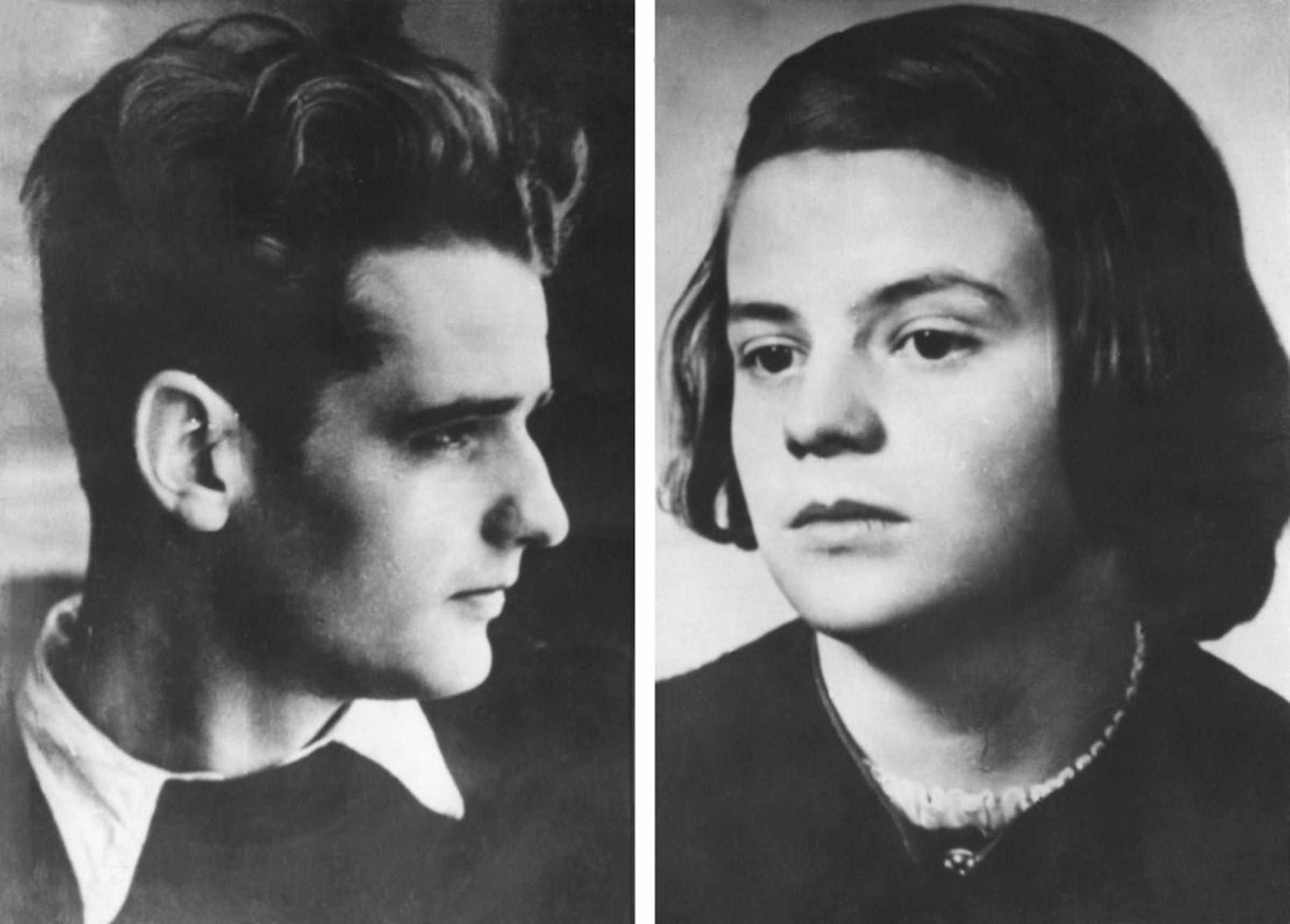

The most famous resisters were Hans and Sophie Scholl, a brother and sister who were executed by guillotine on Feb. 22, 1943, for distributing anti-Nazi leaflets through their underground resistance group at the University of Munich after learning about what was happening at the Dachau concentration camp. Hans and Sophie were 24 and 21 years old, respectively — not children, but, as TIME noted in reported on their deaths, young enough that they “were reared under Hitler’s National Socialism, drilled in its rituals, supposedly imbued with its doctrines.”

“We are your bad conscience,” said one of the leaflets. “Everyone wants to exonerate himself from his share of the blame … But it cannot be done: everyone is guilty! guilty! guilty!”

TIME reported that the pamphlet that got them discovered said: “The eyes of even the most stupid Germans, these eyes have been opened by the terrible blood bath in which Hitler and his confederates are trying to drown all Europe in the name of the freedom of the German nation. Germany’s name will remain forever dishonored if German youth does not at last rise up, avenge and destroy its tormentors and help in the building of a new spirit in Europe. Girl students and men students, the nation looks to us. It expects from us in 1943 the breaking of the National Socialist terror.”

The end of the Nazi regime would not come for another two years.

The world’s fascination with what was forced on young people under that regime — and what young people, under duress or not, did under its influence — has endured much longer. And today, especially amid trends such as the rising presence of white supremacist messages on college campuses, the vulnerability of young people to propaganda is no longer just a matter of historical interest.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com