I Can Get It for You Wholesale was a major Broadway show, written by Jerome Weidman, with music and lyrics by Harold Rome. Arthur Laurents, who wrote the book for West Side Story and Gypsy, was directing. The producer was David Merrick. They were all Broadway royalty, and I thought there wasn’t much of a chance that they’d want to hire me.

That’s my negativity, which I inherited from my mother. She always told me, “Don’t count on anything good, because then God will snatch it away.” And I probably used that negativity to protect myself.

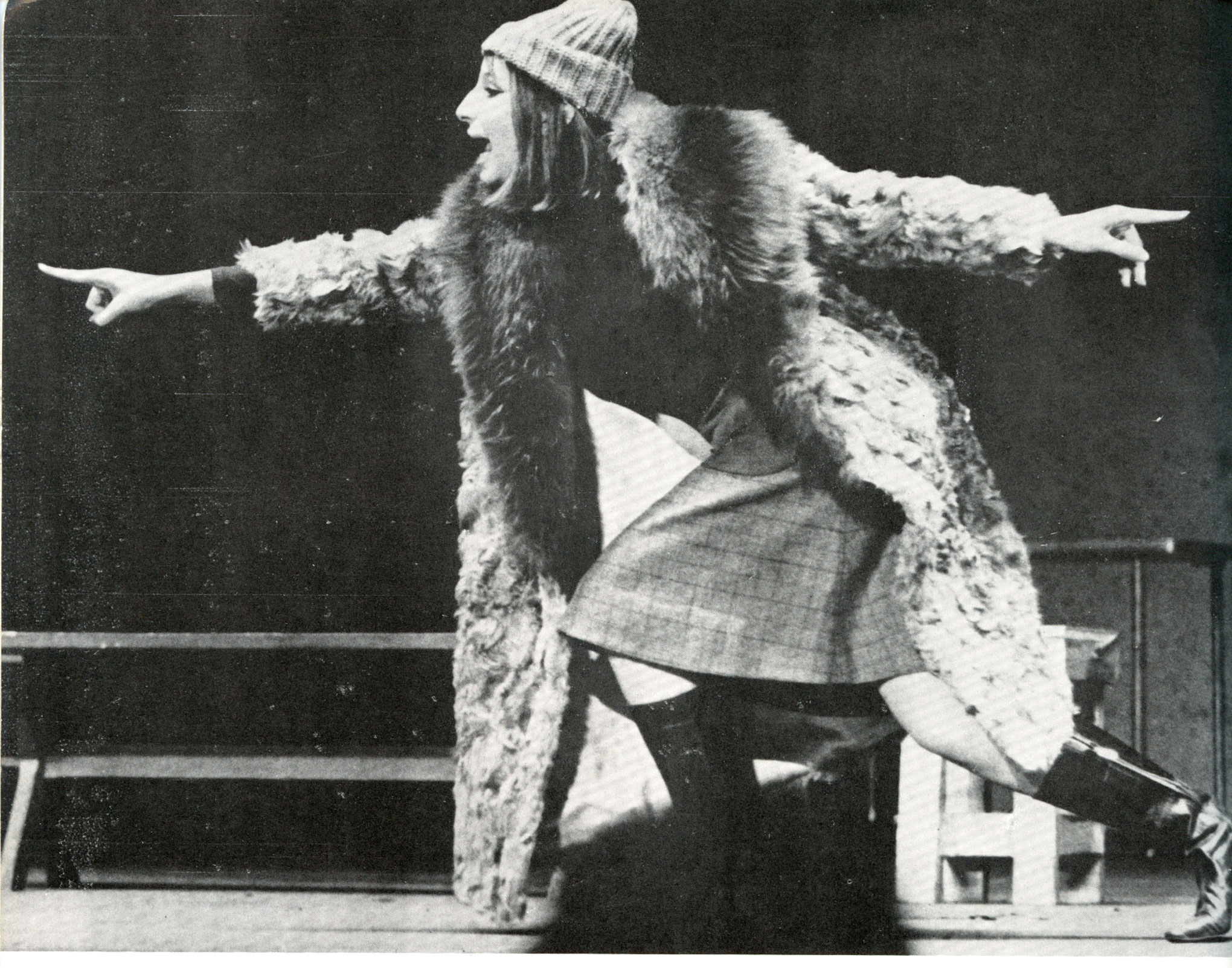

I came in to audition in November 1961. Since the play took place in the 1930s, I was wearing my 1930s coat, to put me in a period mood. It’s made of karakul, the smooth honey‑colored fleece of a lamb, trimmed around the collar and the hem with matching fox fur (this was way before PETA). I bought it in a thrift shop for $10 and thought it was the most beautiful thing I had ever seen. What made it so special was that the inside was just as lovely as the outside . . . the lining was embroidered with colorful baskets of flowers, done in chenille threads, with a little pocket made of ruched silk. Somebody had to really care in order to go to all that effort for something hardly anyone would see. I loved that idea, and I still have that coat. (The lining fabric has fallen apart, but the chenille flowers are still intact.)

Someone announced my name, and I stepped out onto the bare stage at the St. James Theatre, still wearing my coat, so everybody else could appreciate it. But of course whoever was announcing my name mispronounced it, so I had to correct it. As I was explaining this, I was setting down my shopping bag. I always carried some food . . . unsalted pretzels, Oreos (but I have to remove that white guck in the middle), almonds . . . because you never know when you’ll want a snack. I think that idea came from my mother. Maybe it’s part of the collective unconscious of European Jews, because what if a pogrom came and you had to get across the border fast? You have to have a little something to eat until you get to the next country.

Read More: Barbra Streisand Had a Foolproof Way of Proving to Her Mother That She Would Be a Star

I shaded my eyes and looked out into the dark theater, but I couldn’t make out any faces. “Hello! Is anyone out there? What would you like me to do?”

A voice replied. “Can you sing?”

More From TIME

I thought to myself, If I couldn’t sing, would I be standing here? But I said, “I think I can sing. People tell me I can sing. What would you like to hear?”

Nobody answered quickly enough, so I said, “Do you want something fast or slow?” I was like the guy behind the counter in the deli. Order your sandwich, already! Pastrami or corned beef?

Someone said, “Anything you like.”

“Well, this is a comedy, right?” I said. “So I’ll do a comedy song.”

I pulled my sheet music out of my shopping bag and headed over to the piano, not noticing that the pages, which were all attached and folded up like an accordion, were unfurling behind me into a long, 20‑foot tail. Actually, I was only pretending not to notice because I had done it deliberately. I knew I could be funny, and I thought I should show them. I heard some snickers from the audience, so it seemed to be working.

I told the accompanist, “Play the one on top,” and launched into “Value”:

Call me a boob, call me a schlemiel.

Call me a brain with a missing wheel.

Call me what you will, but nonetheless I’m still in love with Harold Mengert

And it’s not because he has a car. Arnie Fleischer has a car.

But a car is just a car . . .

The man who was talking to me . . . who turned out to be Arthur Laurents . . . was laughing, and then he asked, “Do you have a ballad?”

“Oh yeah, I have several.” I turned back to the accompanist and asked him to play “Have I Stayed Too Long at the Fair?” It was a song from another obscure show, and I loved it because it was about yearning, about wanting somebody to care, and I completely related to that.

Jerome Weidman was there that day, and later he described what happened next in a magazine article:

“Softly, in a voice as true as a plumb line and pure as the soap that floats, with the quiet authority of someone who had seen the inevitable, as simply and directly and movingly as Homer telling about the death of Hector, she told the haunting story of a girl who had stayed ‘too long at the fair.’ It was a song, of course, and a good one. But emerging through the voice and personality of this strange child, it became more than that. We were hearing music and words, but we were experiencing what one gets only from great art: a moment of revealed truth.”

I wish I could write so poetically. All I can say is I stood on that stage and went into my own inner world, forgetting anyone else was there.

There was silence after I finished the song. Then they asked me to sing another, and another.

I could hear them talking among themselves, and then Arthur stood up and asked if I could come back in a few hours.

“Why do I have to come back?” I asked. “You didn’t like what you just heard?”

I think Arthur laughed and explained that David Merrick would be there later, and they wanted him to hear me.

“No. I can’t come back,” I told him. “I have to go to the hairdresser.”

I could practically hear their shock. I was well aware that nobody would ever say no to a request to come back for another audition. And I was aware that what I had just said was funny. But it was also the truth.

“I’m opening tonight at the Blue Angel and I have to get my hair done. Hey, all of you should come!”

“Can’t you come back after your appointment?” Arthur asked.

I called out to my manager, Marty Erlichman, who was sitting in the back of the theater, “Marty, do I have time?”

I can just imagine him holding his head in his hands. “Yes!” he said vehemently. “Yes, you have time!”

So I went to the hairdresser, and when I got back to the theater and walked onstage, I asked, “So what do you think?”

They were taken aback, assuming I was talking about my audition. “No, my hair!” I said. “It’s different. Do you like it?”

I don’t think they knew what to make of me.

I sang my songs again for the group, which now included Merrick. It seemed to be going well, but I wasn’t sure. There was clearly some sort of consultation going on down there in the seats. It was only years later that the stage manager, Bob Schear, told me that Merrick called him over as soon as I finished the first song and said, “Don’t let her go. In fact, lock the door.”

I had come in for the part of the ingénue, but now they asked if I would be willing to play the part of the lovelorn secretary, Miss Marmelstein. Arthur said they had been planning to cast the role with an older woman, but now they were rethinking it.

“Sure,” I said. “Why not? After all, I’m an actress.”

Read More: Barbra Streisand Calls Out Hollywood’s Double Standard

They gave me the music to her song and asked if I could come back the following week and sing it for them. On my way out Bob Schear stopped me to make sure he had my address and phone number.

“My address? Well, during the week I’m usually at West 18th Street but then on weekends I sleep in this rehearsal studio on Eighth Avenue.”

He looked confused. “Don’t you have an apartment?”

“No, but I’m looking for one. I read the ads in the New York Times every night and I can’t find an apartment that I can afford.”

“I can ask my landlord,” he told me. “I think there’s an empty apartment in my building.”

It was a tenement building at 1155 Third Avenue, near 67th Street, and Bob’s landlord was Oscar Karp, who couldn’t have been more appropriately named because he also owned the seafood restaurant, Oscar’s Salt of the Sea, on the ground floor. Bob went home and talked to him that night, and it was only after Bob promised to guarantee the rent that Oscar agreed to show me the apartment. It was a third‑floor walk‑up, and as soon as you started up the narrow, bare‑bones staircase, there was the smell of fish.

It was as if I couldn’t escape that odor. My father’s parents owned a fish store, and I still remember the sight and the smell of all those dead fish, packed in ice on slanted metal trays. My grandparents lived over the store, but we rarely visited, because they never liked my mother and blamed her for my father’s death. (That wasn’t fair.)

To this day I can only eat fish that doesn’t smell.

The apartment was a railroad flat, with four little rooms in a line and a bathtub in the kitchen, and the rent was $60 a month. As soon as I saw it, I said, “I’ll take it.” So I, too, would be living over fish. But at least food was close by, and I eventually became good friends with Oscar.

Things were looking up. I had an apartment on the East Side of Manhattan, where I had always wanted to live . . . and that meant I was not going back to Brooklyn . . . and I had a callback for a Broadway show.

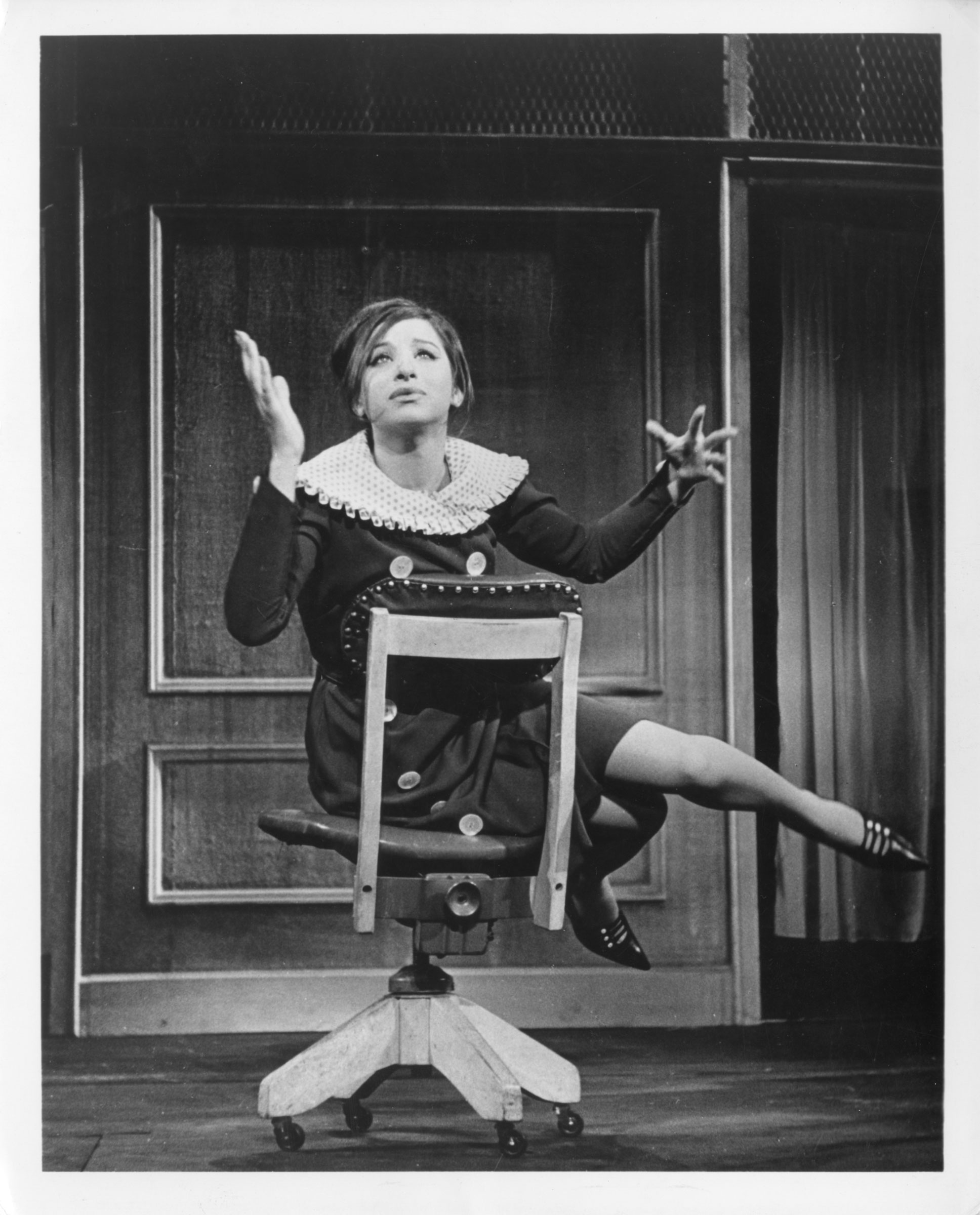

I learned Miss Marmelstein’s song. When I came back to do it for Arthur and the group, I said, “I’d like to sit in a chair, if that’s okay.” I wanted to sing the number sitting down for two reasons: one, because I was nervous and didn’t want to stand, and two, because I thought it would be funny if the secretary did her song in a secretarial chair, the kind on casters, so she could roll around the stage, pushing herself with her feet. I just saw it that way in my head.

Just before I started to sing, I remembered I had gum in my mouth and stuck it under the chair. The song seemed to go well. Everyone laughed, and Arthur said, “Thank you. We’ll be in touch,” or something like that.

Later I found out that Arthur had gone over to the chair after I left and tilted it, to see if the gum was still there. I guess he wanted to know if the moment had been spontaneous . . . had I really been chewing gum? Or was it just a funny bit of business that I had worked out before I got there?

Arthur says there was no gum.

Listen, I wouldn’t have left my gum on their chair, spoiling their property. That’s not nice. The truth is, I pulled it off before I got up and started to chew it again. There was still some flavor left in it.

From My Name Is Barbra by Barbra Streisand, published by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2023 by Barbra Streisand.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Contact us at letters@time.com