These are independent reviews of the products mentioned, but TIME receives a commission when purchases are made through affiliate links at no additional cost to the purchaser.

LaGuardia Airport offers no fewer than four opportunities to purchase Colleen Hoover’s books between security and the gate—this is expected. What feels almost too on the nose is when, an hour into my flight to Dallas, the woman beside me wakes up from a nap and pulls out a copy of Hoover’s best-known novel, It Ends With Us.

I shouldn’t be surprised: Hoover’s books are everywhere. The story of her rise to literary success is straight out of a movie plot, and not a particularly believable one. She was a 31-year-old social worker living in a mobile home with her husband and three boys when she got inspired to start writing a story about a teen slam poet—a way to pass the time while her son was in rehearsals for a play. Hoover’s mom and sisters read the first few chapters and wanted to know what happened next, so she kept going. When she finished, Hoover uploaded the manuscript to Amazon’s self-publishing platform so her grandmother could read it on her new Kindle, and just months later, thanks purely to word-of-mouth buzz, Hoover got the call: her book, Slammed, was a New York Times best seller.

That was in 2012. She’s released 24 more plot-driven romance, thriller, domestic-drama, and young-adult novels and novellas since then (some self-published, some with traditional publishers, some through both). At least 17 have become Times best sellers, and many have lingered on the list at the same time, largely due to a surge of impassioned reviews on TikTok during the pandemic. Hoover, 43, is known for converting reluctant readers into fanatics. Last year, she outsold the Bible.

Read More: Colleen Hoover Is on the 2023 TIME100

More from TIME

Hoover is so popular, in fact, that, as I note my seatmate’s reading choice, I’m flying to Texas to witness her fandom in action, following her behind the scenes of Book Bonanza, the romance-book convention created and run by the author and her two sisters under their nonprofit the Bookworm Box. This year, 2,700 people—including 187 authors—signed up to converge on the Gaylord Texan Resort & Convention Center in Grapevine for two full days of panels, signings, and parties.

Book Bonanza, launched in 2018, is the literary equivalent of a Taylor Swift stadium tour: 15,000 people logged on to try to buy fewer than 2,000 $250 tickets for this year’s event when they went on sale in September, and they sold out in minutes. The resort set aside 1,020 rooms for the group—I got the very last one.

THURSDAY, JUNE 22: 6:12 p.m.

It’s a little past 6 p.m. when I arrive at the private welcome dinner for authors, sponsors, and industry members, and Hoover is nowhere to be found. Thirty minutes pass, then an hour. Partygoers fill the room, hit the taco buffet for seconds. It’s almost 7:30 when she walks through the door in silver platform shoes, blond hair flowing despite the Texas heat wave. Her sisters Lin Reynolds and Murphy Rae Fennell greet her at the front, then head back in. Hoover lingers at the threshold. A self-described introvert who struggles with impostor syndrome, she confesses that she’s nervous about remembering names and recognizing people she’s met before. “It looks really overwhelming in there,” she says, peering into the crowd. She’s able to make it to the bar in the center of the room before guests notice her and she’s snagged. But once she is, that’s it: Hoover is locked in conversation until she makes her exit around 9 p.m. She’ll be in bed by 11—a marathon lies ahead.

FRIDAY, JUNE 23: 7:17 a.m.

On the first official morning of Book Bonanza, the line to claim wristbands—passes that save a spot in line to meet a given author during the signing sessions—officially starts forming at 7 a.m. But by 7:17 when I wander downstairs to the conference center, it’s already hundreds of people long. Readers sip coffee and strategize: only 800 people will get wristbands for Hoover, 800 for Fifty Shades of Grey author E.L. James, and 300 to 800 for the other authors. The Book Bonanza app offers a map showing each author’s location in the hall, but many attendees have been planning for weeks, printed charts on hand. Still, there’s some confusion about which set of double doors will open and who will be let in first. A couple from Corpus Christi tells me they arrived at 4. They hope they’re standing in the right place.

FRIDAY, JUNE 23: 7:48 a.m.

Just 12 minutes before the mad rush is set to begin, I find Hoover in her suite in a hair and makeup chair, two stylists at work at once. She and her husband have been living here for over a week, using it as a home base for family and friends after a storm knocked out their power lines and they gave up on rotating nights in the RV with their kids. The surfaces of the suite are strewn with the remnants of swag-bag assembly and the detritus of living with teenagers. I show her a video of the line downstairs and describe how the heat in the hallway spikes near the cluster of bodies at the front, expecting this to be received as good news. But Hoover’s mind goes straight to worry: “I hope they’re blasting the AC.”

Hoover worries a lot. She worries every book she writes is the last one she has in her. That every new best seller is a fluke. That her latest rerelease, Too Late, which is a darker read, will get shelved with her more innocuous romance novels and she’ll “traumatize a generation.” Hoover has come to realize that being a public figure comes with tremendous pressure. She doesn’t do the heavy lifting of planning Book Bonanza anymore—there’s a team for that. “The only stress that I get from this event,” she says, holding still for the makeup artist, “is the fact that whatever goes wrong is going to be on my shoulders, because it’s my name.”

That same unsettling awareness arose earlier this year when she posted a photo from the set of Justin Baldoni’s film adaptation of It Ends With Us. Hoover spent two weeks in May and June in New Jersey where the movie is being filmed with Baldoni directing and starring opposite Blake Lively. She gave feedback on the footage they’d captured so far, correcting pronunciation of certain terms and flagging moments in the script that might cause confusion. And she filmed two cameos: one at a party, where she and other extras danced all day to imaginary music, and one as a customer exiting the flower shop owned by Lively’s character Lily. The photo Hoover posted was of herself in front of the shop, and soon after, WGA members, who are on strike, demonstrated outside the set. “I was like, did that cause the picketers to show up?” she says. “I don’t know.” A couple weeks later, production officially shut down. (This was the real reason they had to hit pause—it was not, as some on TikTok seem to believe, because of persistent ragging on Lively’s folksy costumes, which Hoover insists look better in person.) The filmmakers seem confident they’ll be able to complete their work soon: It Ends With Us will be released on Feb. 9, 2024, according to the Hollywood Reporter.

Read More: How the Writers Strike Will Affect Your Favorite Shows

Production delays notwithstanding, Hoover feels assured her book is in good hands: “They really are sticking to the book,” she says. And she loved being on set so much that she and her assistant Claudia Lemieux each got the phrase “had a blast” tattooed on their forearms.

There’s more Hollywood glitz to come. Amazon has optioned the screen rights to another of her biggest titles, the psychological thriller Verity. She read a script two years ago and hasn’t heard much since, but it’s the book she’d most like to see come to life onscreen. Her book Regretting You is currently under option as well. “Everyone keeps coming trying to make a blanket offer,” she says. “I would never sell everything to one company, because what if I don’t like how they do it?” Hoover is taking greater control over her business: she has partnered with producer Lauren Levine, who worked on a 2017 adaptation of Confess, to create a production company of her own. “Why am I selling my rights for them to do whatever they want with it,” she says, “when I could actually be a partner in this?”

FRIDAY, JUNE 23: 8:46 a.m.

Hoover changes into a black dress she originally bought to wear for a funeral-scene cameo in It Ends With Us and grabs the 40 oz. tumbler of Diet Pepsi she keeps with her at all times. A security guard escorts her through the bowels of the resort to meet Jenna Bush Hager and film a quick scene for the Today show before they sit down together for the convention’s opening panel. Moments before she’s set to go onstage, Hoover presses her hands into a table and braces herself. “I wish I was the kind of person who microdosed,” she says.

But the conversation flows seamlessly, Hoover appearing relaxed and in her element, even shedding a few tears when talking about Reynolds, who was diagnosed with early-onset Parkinson’s this year, and their choice of the Michael J. Fox Foundation as one of the convention’s beneficiaries. After the talk, she tapes a separate interview with Bush Hager in the resort’s steak house. Then, as Book Bonanza attendees begin lining up again to enter the conference hall for the signing session, Hoover ducks out for a quick nap. It’s only noon.

FRIDAY, JUNE 23: 1:57 p.m.

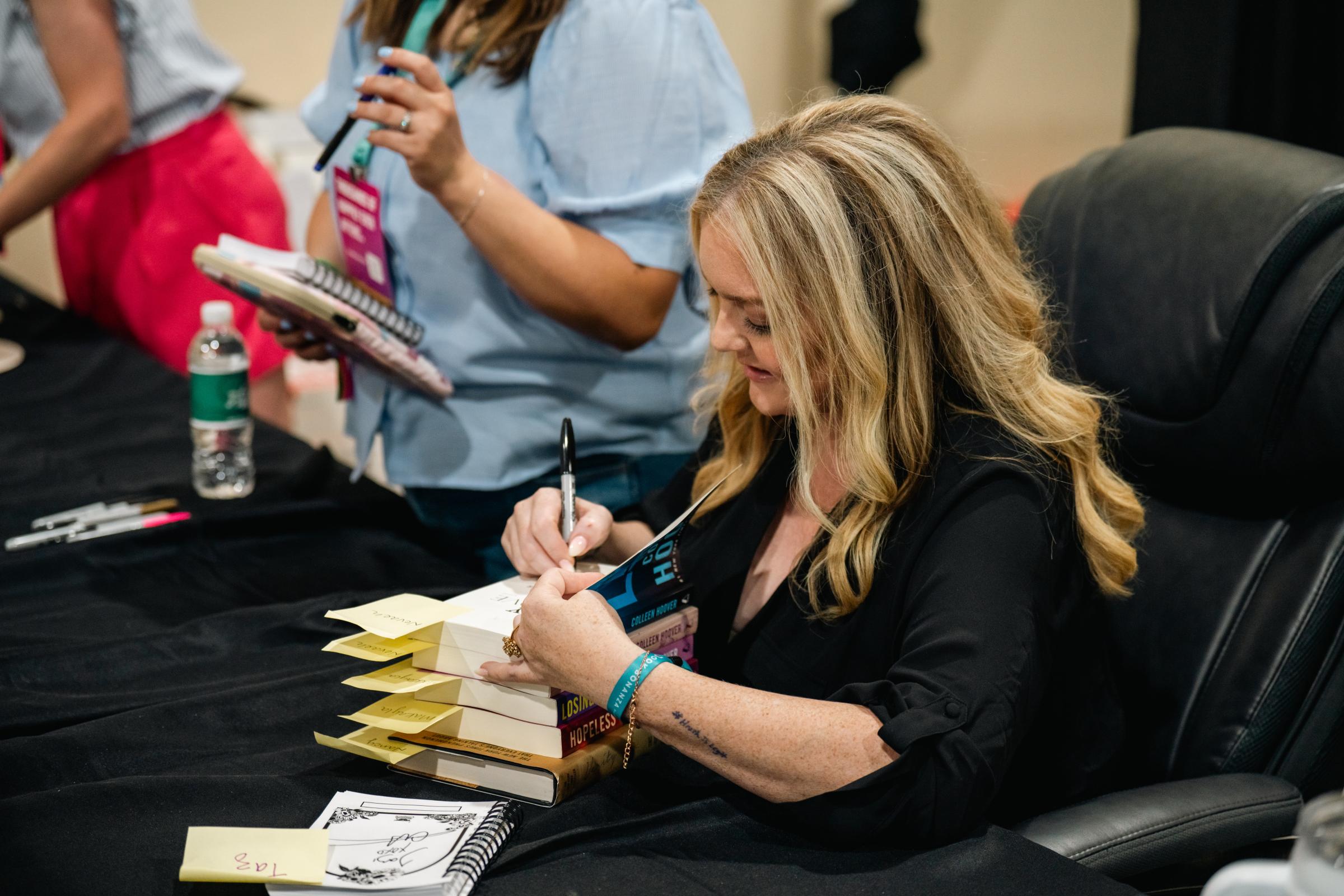

Across the signing room—a concrete cavern now lined with glittering, balloon-decorated booths—authors and volunteers are setting everything just so, getting into position to embrace the chaos to come. Hoover takes a seat behind a long table set with free bits and bobs for her readers: pins and ribbons emblazoned with CoHo and CoHort, the nicknames her fans have given her and themselves, bookmarks, pens. Lemieux, standing by Hoover’s side, wears a sample sweatshirt, emblazoned with lilies and a quote from It Ends With Us, from Hoover’s first official merch line, which they’ll launch in November. Lemieux has big dreams for her boss: “I’d love to put her in a position similar to J.K. Rowling,” she says. “I really do want to build an empire with her.”

If Book Bonanza is any indication, she’s on the way. When readers rush to line up to meet Hoover, there are women from Tennessee, Colorado, Oklahoma. A 52-year-old from Fort Worth in Eras tour merch who loves both Swift and Hoover for the way their work gets her out of her head. A 23-year-old from Atlanta who hated reading until she tried Verity, binged every one of Hoover’s books in the next month, and ditched her interior-design degree to work in book publicity with her mom. In-the-know readers have come prepared with rolling carts—$17 on Amazon, I’m advised—to tote around all their signed books and merch.

Read More: 8 Ways to Read More Books—And Why You Should

At Hoover’s table, fan bear gifts—candy, slippers, hand-knitted stuffed unicorns, a mini foam roller to relieve symptoms of carpal tunnel, should she ever need it. For Hoover to sign, they bring hardcovers, paperbacks, Spanish language translations, rare printed copies of a book self-published by Hoover’s best friend Tarryn Fisher that Hoover put her own face on as a prank. They also bring cowboy hats, protective neoprene cases for paperbacks, hand-painted posters, travel mugs, wooden wall hangings. Hoover has three women helping her at once, noting names and spellings, managing the Sharpie supply, snapping photos, and encouraging fans onward.

These interactions last less than 60 seconds, but readers leave beaming, shaking, and, later in the day as overstimulation sets in, crying. A fan shows Hoover her tattoo inspired by her unlikely love story Heart Bones. One woman apologizes for her sweaty palms and makes a flustered request: “Could you please write it for Maureen, so my mother-in-law will like me more?” Another who approached with an armful of Hoover books has somehow forgotten her copy of her favorite, Layla, so Hoover gives her one for free. When she walks away to meet her friend, tears are welling in her eyes and she’s so overwhelmed she can barely speak. Everything slows for a moment when a woman brings the program for her mother’s memorial service and shows Hoover the quote from Reminders of Him printed on the back. Hoover stands to give her a deep hug.

For four hours, the line never lulls. Sharpies run dry, and Hoover chucks them over her shoulder, a new one appearing in her hand. Dead markers fly in my direction every now and then, and when Hoover remembers there’s a person where there usually is not one, she swivels around, horrified. She gulps down a bottle of 5-Hour Energy and takes two swift, escorted bathroom breaks. By 6:07 when the signing period ends, Hoover’s out the back door, her husband beside her. “My face hurts from smiling,” she tells him. “But it was a good day.”

SATURDAY, JUNE 24: 1:05 p.m.

It isn’t until lunch on the second full day of Book Bonanza that Hoover has time to sit and talk. After back-to-back panels—one about the popular trope of second-chance romance and one about the editing process moderated by the publisher of Atria—Hoover makes her way to the signing room, where the team is setting up for round two. She hugs everyone hello, then rolls her chair into the makeshift staging area behind her table, a cramped space created by black curtains, and props her feet up on some empty boxes. “It can be a very intimate interview,” she says, then jokes, “You want to sit on my lap?”

Hoover has a disarming casualness about her—she so clearly thinks of herself as the same person she’s always been. If you ask about her biggest challenge in life, she’ll talk about her family, how she and her husband have just become empty nesters, and now they have to figure out what’s next. “I feel very disconnected from the statistics, all of the stuff that’s out there about the year or two I’ve had,” she says, dragging a sip from her Pepsi cup. “I’m not walking around my house going, ‘I outsold the Bible, honey, you need to make my dinner tonight.’”

Read More: Why We Can’t Stop Reading Colleen Hoover’s Trauma-Filled Novels

That sense of distance is a theme—none of this feels real to her, and she’s adamant that she doesn’t want it to. “I don’t know that I want to accept that it’s as big as it is, because it terrifies me,” she says. She used to enjoy telling the fairy-tale story of Slammed, but now she feels “almost ashamed” of how she burst onto the scene. “I feel like I haven’t paid my dues. There are so many writers who are such good, literary writers who have been hoping to hit the New York Times or find their audience for years, and it happened to me in a matter of months almost by accident,” she says. “I know I can’t compare my story to other people’s, but the more I tell it, the more guilty I feel.”

Reynolds noted earlier that the week before Book Bonanza, the number of Hoover’s titles on the Times paperback fiction list dropped (from six to five). And when someone shared the news, Hoover exhaled and thanked God: “She was like, OK, enough, this is getting awkward.”

“I can’t explain it,” Hoover says. “I just hate the attention. And I hate saying that because I don’t want to seem ungrateful.”

Success has not come without controversy or criticism. Hoover’s books are often maligned by more literary audiences. And It Ends With Us—which tells the story of Lily, a woman who was raised in an abusive household and falls in love with a neurosurgeon named Ryle who turns out to be violent—has been denounced for simplifying and normalizing domestic violence. Hoover contends that she never set out to educate; she merely wrote a book inspired by her own mother’s experience getting out of a violent marriage. “And I did simplify her abuse,” she says. “I simplified what she went through. Ryle is a nicer character than my dad was.” At the same time, many readers have asked her to write a book from Ryle’s perspective, which she says makes her sad. “They just don’t realize what a slap in the face it would be for all the women who have read this book and left their abusive marriages,” she says. The author is generally averse to making declarative statements about what she will or will not write, but she’s unequivocal on this: “I will never write a Ryle redemption story.”

Other controversies have bubbled up, including a misguided announcement of plans to publish a coloring book based on It Ends With Us (“I can absolutely see how this was tone-deaf. I hear you guys and I agree with you. No excuses,” Hoover wrote on Instagram). And as Hoover’s audience has grown beyond her strictly supportive community of readers, she’s faced both personal insults and critical press. “I could sit there and read reviews all day and have to go to therapy and take Xanax, but I don’t want that life,” she says. “Luckily, I’ve always had a healthy relationship with the fact that I’m creating art. It’s going to have people who hate it and people who are moved by it. I just want to focus on the people who find entertainment and value in what I’m writing and ignore the rest of it.”

There are enough people who love Hoover’s books that her financial reality has drastically changed. Earlier that morning, Reynolds had detailed Hoover’s generosity, telling me about houses she had purchased or built for her grandparents, aunts, and her mother and stepfather, cash she’d offered to other family members, and the dream car she got for her sister: a Cadillac SUV that Reynolds once put on a vision board.

For herself, Hoover is thinking about travel. Most of the trips she’s taken have been for book tours, but she tells me she wants to get out on the road in the RV with her husband—the plan would be to keep writing while they camp. This is when she also confesses that for the first time in her career, she recently missed a deadline. “I’m so far beyond it at this point that I feel like it doesn’t matter anymore,” she says. “And now they’re like, just write a book when you can. We’ll be happy to get it.”

It’s easy to understand how she could fall behind—the demands on Hoover’s time never cease. After 30 or so minutes in our hiding spot, the din of the signing room growing ever louder, Lemieux pokes her head in: it’s time to get ready.

SATURDAY, JUNE 24: 2 p.m.

The Saturday signing is more of the same, only more intense, if that’s possible—there’s a sense of urgency in the air given that today is the last chance to meet the authors. Readers charge into the hall, carts rolling behind them, plans of action in place. Many sport the Colleen Hoover-branded neck fans that came in the welcome bags.

For four hours, fans lay their treasures before Hoover, soaking up her attention. Then every author but she clears out of the hall. A little after 6 p.m. the doors have closed and volunteers have started breaking down tables, popping balloons, packing everything up, but Hoover is still signing. A pregnant fan drags a chair through Hoover’s line, taking a seat every few minutes. A woman who lost her cool when she missed her chance to meet Hoover earlier talks her way into the last slot of the day. The author stays focused, giving each reader their due time. At 6:40, a woman in her 20s shares that she drove all the way from Ohio by herself, and even Hoover gets teary. By 6:50 the ticket holders are gone, but Book Bonanza volunteers start trickling over, hoping to share a moment with Hoover before she leaves. Even one of the event photographers hands her camera to Lemieux so she can get a photo. It’s 7:22 by the time Hoover disappears out the back in pursuit of a moment’s rest and a slice of pizza.

SATURDAY, JUNE 24: 8:27 p.m.

Hoover sat out last night’s party—the theme was Mardi Gras, and that’s all I can say about it, because I went straight to bed, too. But tonight is when Hoover and her sisters preside over the closing ceremony and kick off the goodbye party, dubbed Boots & Bling. There’s a mechanical bull in the back of the ballroom and a stage up front where Hoover, Reynolds, and Fennell step out in cowboy boots and colorful prints.

“Are you going to ride the bull?” Reynolds asks her sisters.

“Listen, I tried to get over there and ride it before y’all got in here, but I couldn’t,” Hoover says, gesturing to the crowd. “I’m not doing it with all these people in here. I’ve got a dress on.”

By the end of these intense two days, there’s a strong family vibe in the room. I strike up a conversation with a woman bent over her Kindle and she tells me she thinks Hoover’s friendship with Fisher has influenced the former to write darker books. She speaks as if she knows them: “Tell Colleen to spend more time with Tarryn.”

Onstage, the sisters invite representatives from Reach Out and Read and the Michael J. Fox Foundation to join them—this is the part that makes Hoover forget the stress of the event each year and want to do it all over again. Toting cardboard checks, the trio presents $110,000 to each organization, with Hoover making a last-minute announcement that she’s throwing in $30,000 to KultureCity to make it an even $250,000.

“Y’all did this!” Reynolds shouts to the crowd. The sisters announce the dates for next year’s convention—June 13 to 15—and raffle off tickets and comped hotel stays to two ecstatic winners.

In theory, Hoover’s day should end here. She should slip away with security and wind her way back to her suite. But she’s learned that not everyone who received a wristband for her line actually made it to see her. So she has told the room that anyone who was promised the chance will still get it—she’ll set up a booth in a corner down the hall. (“I’m a little buzzed,” she warned before presenting the checks, “so if my spelling’s wrong…” There was a loud “We love you!” from somewhere in the audience.)

The line forms almost immediately after Hoover and her sisters finish onstage. I count 10, 20, 40 people—and more are on the way, having dashed back to their rooms to collect their books. In a few minutes, Hoover will take a seat behind her table. But there’s a problem to be solved. A staffer looks nervously down the line and makes a plea: “Does anyone have a Sharpie?”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- How Far Trump Would Go

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- Saving Seconds Is Better Than Hours

- Why Your Breakfast Should Start with a Vegetable

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Ryan Gosling

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Lucy Feldman at lucy.feldman@time.com