In 40 minutes, the former grocery bagger from Puerto Rico will try on outfits worth thousands for the cover of this magazine. In 12 hours, he will be photographed embracing the world’s highest-paid supermodel. In one month, he will be staring out onto a sea of 125,000 superfans from the heights of Coachella’s main stage.

But right now, Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio, who also goes by Bad Bunny, is slouched almost completely horizontally on a green-room couch in downtown Los Angeles, thinking about being with his parents back home in Puerto Rico.

“Outside of that house, perhaps the world is listening and talking about me,” he murmurs in Spanish. “But in that house, everything is the same. Nothing has changed. It’s beautiful for me to go there and they still look at me with the eyes of, ‘Come here, Benito Antonio. The baby. The son.’”

Bad Bunny wants to be the biggest artist in the world—and he is. Last year, his fifth solo studio album, Un Verano Sin Ti, was Billboard’s top-performing album of the year, beating out Taylor Swift and Harry Styles. He broke the all-time record for tour revenue in a calendar year—with $435 million earned—and was Spotify’s most streamed artist for the third year in a row. But Bad Bunny also wants to just be Benito; to do whatever he wants, or hace lo que le da la gana, as he named his sophomore album. And until this point, it is exactly this mentality that has brought him unprecedented success. Where other musicians reaching for his level of stardom have hidden certain parts of themselves, Benito has refused to compromise: on the language he sings in; the political stances he assumes; the dresses and nail polish he wears.

Bad Bunny is perhaps the world’s first reverse crossover artist, whose success comes from a refusal to cater to the mainstream. His stubborn originality, independence, and fiercely local lens have made him a radically new kind of global pop star, etching pathways to success that completely bypass New York or Hollywood industry gatekeepers.

But the further Benito ascends into the stratosphere, the more the expectations of his growing fandom threaten to exceed what his whims can deliver. His unequaled stature means he is often asked to speak for an entire region, a responsibility that he alternately embraces and chafes at. During the course of our conversation, he dances around political questions and refers to himself as a chamaquito—a little boy.

Seven years into his career, Benito, 29, is a legitimate heir to Frank Sinatra, Michael Jackson, or Beyoncé. How he navigates this next fraught period could determine how close he can come to meeting the near impossible expectations placed on him by his fans, his homeland, an exacting industry—and himself.

“I always say that if a thousand people listened to me and I performed once a month at a little place, just with that I would be happy,” he says in his deep baritone and distinctly Puerto Rican inflection. “But the hunger and the passion that I have for this is impossible, because I always want to give more and more and more.”

In 2022, Bad Bunny had the type of pantheon year that even other pop superstars dream about. Un Verano Sin Ti topped the Billboard charts for 13 non-consecutive weeks, with the least played song on the record racking up 190 million Spotify streams. In November, Un Verano Sin Ti became the first entirely Spanish-language album to receive a Grammy nomination for Album of the Year.

Benito’s success starts with his inimitable singing voice, which is malleable enough to be imbued either with cutthroat swagger or pathos. He’s a master aural chemist, melding together decades of Latin music into cutting-edge mixes that resonate at the club, on the beach, or at home on a lazy Sunday afternoon. And he creates at a startlingly fast pace. “I’ll send him an idea and tomorrow night, there are vocals in an email that don’t need any adjustments,” the producer Tainy, who is one of his main collaborators, tells TIME.

Benito has achieved all of this without releasing a single song in English, or making any real attempt to cross over. Other Latin artists have scored megahits in Spanish: Ritchie Valens’ “La Bamba” back in 1958, Los Del Río’s 1993 hit “Macarena,” Luis Fonsi’s “Despacito” in 2017. But U.S. interest has ebbed and flowed, with subgenres like Latin pop and reggaeton—a genre that blends Jamaican and Latin musical influences with hip-hop elements—dismissed by industry insiders as fads.

Bad Bunny grew up in the midst of reggaeton’s first mainstream moment. San Juan, P.R., and artists like Daddy Yankee and Ivy Queen played crucial roles in the genre’s evolution in the ’90s and ’00s. As a teenager, Benito listened to reggaeton and other forms of Latin music, and anointed himself Bad Bunny based on a childhood photo taken of him in a bunny costume. He started recording in his room and uploading songs to Soundcloud, and his first hit, “Diles,” blew up when he was 21. Five critically acclaimed and commercially successful solo albums followed, along with a Super Bowl performance with Shakira and 10 music videos that have each surpassed a billion views on YouTube.

Read More: Allow Bad Bunny to Teach You Puerto Rican Slang

You don’t accomplish all this without being relentlessly motivated. When asked whether he cares about maintaining his position at the top, he says, “I always say no, but I think I lie. Because if there is someone who made a cabrona song, I am going to make a more cabrona song.” The word cabrón, which is a stronger vulgarity in some cases, often signifies “badass” in Puerto Rican slang.

All this has unfolded against the streaming boom, which has given fans direct access to regional music. Executives are now focused on sheer streaming numbers as opposed to radio spins, and Latin music is growing faster than any other genre in the U.S. No one is streamed more than Bad Bunny. He has proved to the industry that hits don’t need to be manufactured by Max Martin’s assembly line: that they can be freestyled on an island 3,000 miles away from Los Angeles.

While accepting a Grammy onstage in February, Benito dedicated his trophy to Puerto Rico, where his journey began. He grew up the oldest of three brothers in Almirante Sur, a rural area in Vega Baja, a 45-minute drive from San Juan. His parents, a truck driver and a teacher, went through both easy and “difficult times to bring us food,” he says. All the while, they filled their Catholic household with salsa and merengue music from stars like Héctor Lavoe and Elvis Crespo.

Benito’s rise has paralleled a particularly tumultuous period in Puerto Rican history. In 2016, the same year he released his first single, Congress enacted the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act (PROMESA) in an effort to restructure the island’s estimated $70 billion in debt. The federal law resulted in austerity measures that have cut back on public services for the island, which has one of the highest poverty rates in the U.S. Puerto Rico was under Spanish colonial rule for 400 years before transitioning into a fraught, century-long commonwealth relationship with the U.S., which has been marked by such indignities as coerced sterilization. Debates surrounding statehood have been in limbo since the population first voted on a status referendum over 50 years ago.

During Hurricane Maria in 2017, one of the deadliest natural disasters and the largest blackout in U.S. history, Benito’s parents lost power for months. In 2018, after President Trump visited the island and threw paper towels into a crowd, Benito declared on The Tonight Show that “more than 3,000 people died and Trump is still in denial.” In 2019, he put his tour on hold to join protests in San Juan calling for the removal of Governor Ricardo Rosselló.

Read More: How Puerto Ricans Are Fighting Back Against the Outsiders Using the Island as a Tax Haven

Benito is increasingly careful with his words on politics, conscious that being the biggest Puerto Rican star in the world comes with the ability to shift public discourse. Whereas a 2019 Instagram post encouraging Puerto Ricans to join him in protest was direct, his comments today are more equivocal. “I think the [U.S.] government has failed Puerto Rico,” he says, before backtracking slightly. “It’s failed the United States. Equally, Puerto Rico has failed Puerto Rico. I believe that all governments have failed their country at some point.”

His music is less inhibited. His 2022 song “El Apagón” rails against Puerto Rico’s current Governor Pedro Pierluisi and the constant power outages since its electrical grid was privatized. Instead of a traditional music video, Benito released a short documentary alongside independent journalist Bianca Graulau about the displacement that has resulted from Act 60, a law that offers tax incentives to foreigners.

Benito makes music that reflects the multi-faceted experience of life itself, moving within a few verses from lyrics about sex to Puerto Rico’s lack of infrastructure. He isn’t interested in making reggaeton that’s only perreo (dance-party tracks), nor is he trying to make politically correct records for an older, more conservative, and vulgarity-averse Latino demographic.

Read More: Bad Bunny Speaks Out on Black Lives Matter Protests

His songs and acts of political resistance are widely celebrated—and are now even the subject of at least one college class. But his ascendence has not come without criticism. In 2020, many on social media called out him and other urbano artists for failing to engage in conversations about anti-Blackness following the murder of George Floyd, especially given reggaeton’s history of rewarding white-presenting artists while neglecting its Black roots. Benito is white-presenting, but is often referred to as jabao, a Puerto Rican of mixed race.

When Benito is asked whether he believes race and colorism play a role in the success of a reggaeton artist, he responds, “Because I haven’t seen it or lived it, I can’t say. It’d be irresponsible of me to say yes. They asked me about if [’00s reggaeton superstar] Tego Calderón would’ve been bigger if he wasn’t Black. But in my eyes, Tego Calderón is the biggest singer in the industry.”

Music historian Katelina “Gata” Eccleston of Reggaeton Con La Gata, who has long studied reggaeton and its racial elements, calls Benito a “great ambassador,” and believes that no one artist should be held accountable for the industry’s failures around colorism. Still, she says Benito’s comments above show that “he still does not understand his positionality.”

Benito is frustrated by how his political lyricism seems to necessitate his answering political questions on behalf of the millions of disparate residents of his home island. “That question could be a bit unfair because I simply do a song and then a responsibility so big falls on you,” he says. “You’re not going to ask Daddy Yankee something like that.”

Over the pandemic, Benito hunkered down in Puerto Rico. Now, he often finds himself in Los Angeles, which is where TIME meets him on a balmy March morning. He arrives in fashionable yet comfy clothes: baggy Balenciaga sweats and a yellow-trimmed Moncler puffer jacket covering a shirt of the Mexican pop icon Juan Gabriel. His accessories include Y2K-style sunglasses, a skull ring, mismatched heart earrings, blush-pink nails, and three layered gold chains.

Read More: Reggaeton Is So Much More Than Party Music. This Podcast Breaks Down Its Political Roots

Over the course of several hours, Benito speaks in hushed tones, at times raising his voice excitedly to punch home a point or jokingly insult a member of his posse sitting in the corner. Later on, he teases playing an unreleased song, reaching for his phone in jest.

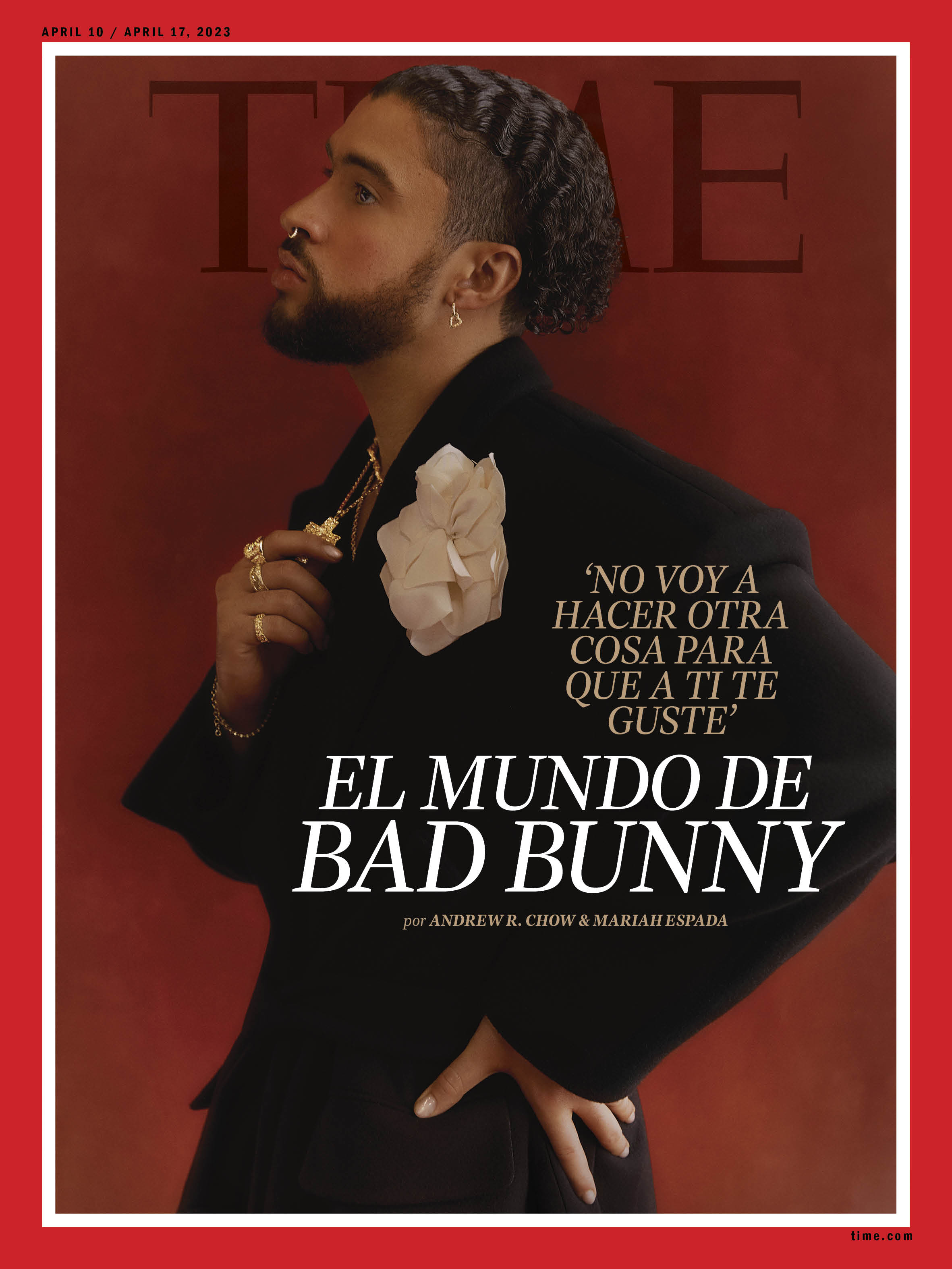

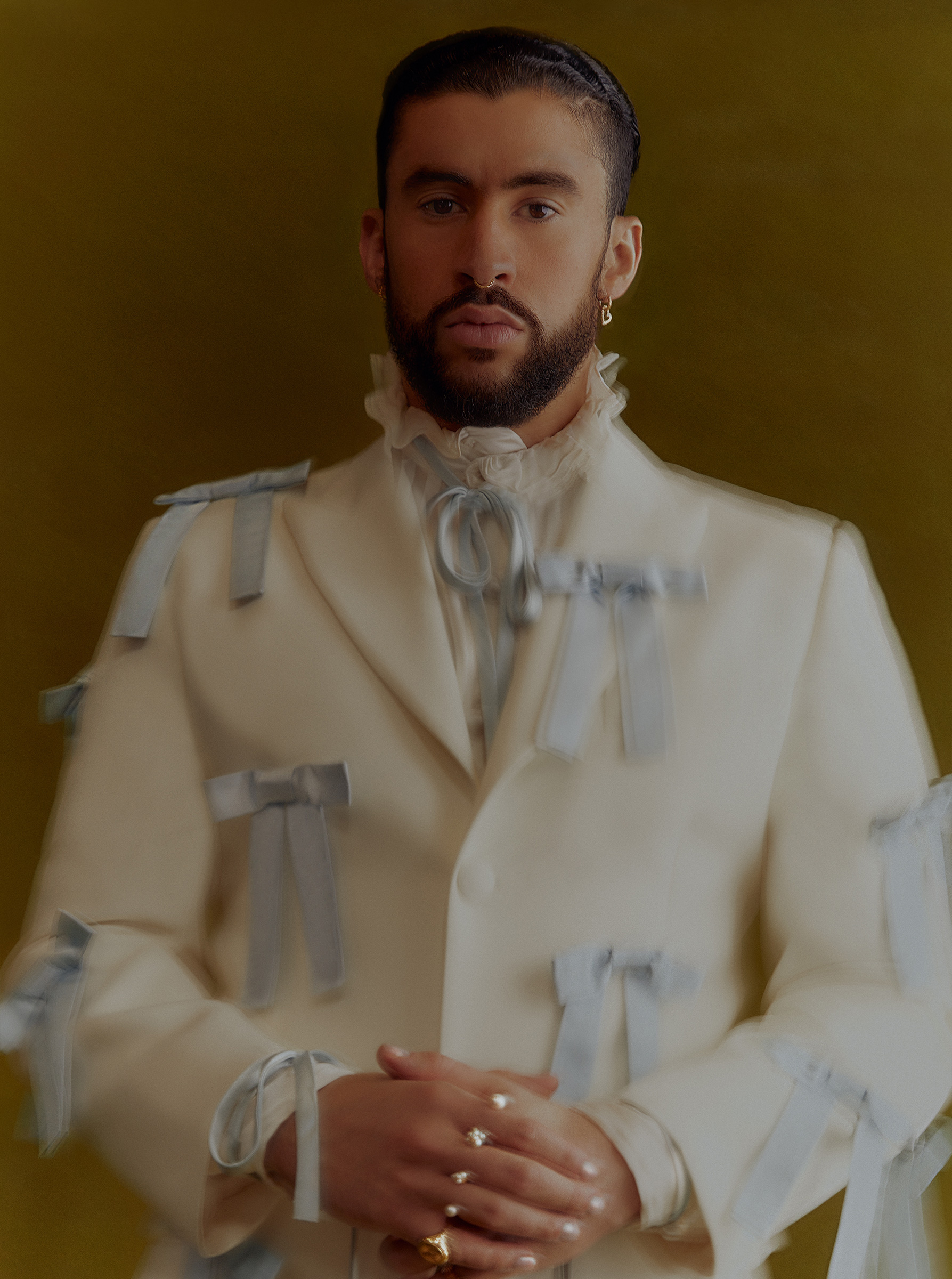

Benito’s attention to detail is apparent as he prepares for the photo shoot. Wearing a floor-length Willy Chavarria coat and a sizable white flower on his chest, he makes his way through piles of jewelry before adding a pearl necklace to his already well-adorned neck. “Beautiful. Me gusta,” he says in Spanglish as he looks in a mirror.

Los Angeles’ appeal to Benito includes Hollywood, which he is keen to immerse himself in. He recently appeared in Narcos: Mexico and Bullet Train, which featured him in a life-or-death brawl opposite Brad Pitt. David Leitch, Bullet Train’s director, says that Benito was fastidious about learning the fight choreography, asking to rehearse scenes over and over. “I’d love to do an action movie where he’s the lead,” Leitch says. “He has a soulfulness and an incredible empathetic quality.”

Benito also appeared in biopic Cassandro, in which he plays a paramour to Gael García Bernal. “My first kiss for a movie and it was with a man,” he says, laughing. “That’s the penalty I get for being with so many women during my life.”

He took the job seriously. “If you’re acting, you’re being someone you’re not,” he says. “So when they asked me for that, I said, ‘Yes, I’m here for whatever you want.’ I think it was very cool; I didn’t feel uncomfortable.”

Read More: The Best Latin Songs and Albums of 2022

Benito is part of a rising generation of male pop stars challenging stereotypical masculine ideals. He has kissed a male dancer onstage, appeared in drag, and declared that his heterosexuality does not define him. He used a 2020 appearance on The Tonight Show to call attention to the murder of a transgender woman, Alexa Negrón Luciano, in Puerto Rico. This month, he will receive GLAAD’s Vanguard Award for his LGBTQ allyship.

Last year, Sony Pictures announced he would star in a Spider-Man spin-off, El Muerto, as Marvel’s first Latino superhero. At the time, Benito said that the role was “perfect” for him, as he grew up watching wrestling and called his 2021 WWE Wrestlemania debut “the best day of my life.” But during our interview, Benito feigned confusion when asked about the movie and said that no filming had yet taken place. Benito’s publicist said that the movie was “at a standstill,” and later clarified that it’s “in development.” (A representative for Sony declined to comment on the record.)

“Maybe they’ll switch me out for Pedro Pascal,” Benito says jokingly.

Benito’s Hollywood dreams are sometimes dampened when he encounters a lack of understanding about his homeland: “If I hear something very ignorant about my country or my culture, I always try to educate them, like ‘No, it’s not like that.’” At the Grammys in early February, his exuberant opening number was nearly overshadowed by the program’s live captioning, which read “singing in non-English.” “It was porqueria (crap),” Benito says dismissively.

He is currently preparing for his Coachella performances, which will take place on April 14 and 21 in Indio, Calif., and mark the first time a Latino artist has headlined the festival. Coachella has hosted massive stars, but the gig doesn’t seem to faze him. “Am I supposed to feel something?” he asks incredulously. “I felt more pressure at the Hiram Bithorn [Stadium in Puerto Rico] than I feel for Coachella.”

Read More: Bad Bunny Is on the 2021 TIME 100

The bigger he gets, the more invasive his fans have become. In January, he was filmed throwing a fan’s phone in a nearby body of water after she started to film them together. “I always say I will never say no to someone who comes up to me to say hi. If you’re coming up like you’re going to rob me, then yes, it’ll bother me,” he says. “Why do you want a picture with me? Because I’m the Statue of Liberty? I’m a human. Greet me.”

Several hours after the interview, Benito ignites another firestorm when paparazzi photograph him embracing supermodel Kendall Jenner, a member of the Kardashian dynasty. Many Latino social media users treated this potential romance as a fundamental betrayal. Benito has often sung about his love for Latin women and culture, even dismissing the non Latinos who want to participate in reggaeton culture or take advantage of Puerto Rican land as lacking sazón (flavor). “It ain’t Benito no more, it’s Ben,” went a common refrain on social media.

Benito declined to comment on the dating rumors. But he says he feels less strongly about the sazón lyric than when he wrote it. “I was upset,” he says. “But now that feeling has passed me. Our culture and music impacts people in other places. They want to try it and feel it. So why am I going to be bothered by that, if they do it with respect?”

Benito says that the “only reception” for his music he cares about is from Puerto Rican fans. But he also says he remains unbothered by his critics. “When I read comments that say, ‘Bad Bunny now I’m not going to listen to your music,’ that’s fine,” he says. “I’m not going to do something else for you to like it. There are plenty of artists, and perhaps you’ll find someone you’ll like.”

As much as Benito purports to be carried downstream by his desires, he also acutely understands the fleeting nature of fame. “I release an album now and a week passes and 15 new albums have arrived,” he says. “So to maintain yourself right there in the position at the top is way more difficult than before.”

Read More: The 10 Best Albums of 2022

Bad Bunny doesn’t have to change anything: he’s already fulfilled the dreams of so many Puerto Ricans and flipped the music industry on its head. Musically, he will continue to do whatever he wants: while he decorated his studios with a tropical decor for Un Verano Sin Ti, he says that lately, his space embodies a ’70s vintage vibe. He has continued to record music this year, he says, but without a specific deadline.

Yet because he loves being on top, he is realizing that some compromise may be necessary in order to stay there. This includes learning more English. “There’s a lot of things that I’m losing, like opportunities, ’cause the language,” he says in English. “I didn’t care about [learning] English. But now, I think I care.” He adds that any English-language song he writes will be on his own terms: “The day I feel like I need to do a song in English, I’ll do it because I feel it.”

The social media fallout of the Jenner photo reinforced how every one of his personal choices is scrutinized through a larger cultural lens. This is a heavy weight to bear for someone who, as much as he genuinely cares about his country, doesn’t feel like an island’s fate should fall on his shoulders alone.

“I am a chamaquito, and we have different preoccupations and desires to do one thing one day and the next not. One moment we go to the club to drink and smoke, and tomorrow I want to be chilling at home watching a movie. And then next I’ll be thinking about my ex or a girl that I like,” he says, sitting slightly more upright than when the interview began. “And then tomorrow I am bothered over something I think is an injustice. But then by night I go to eat tacos, they give me a bit of tequila, and I’ve forgotten.”

—With reporting by Israel Meléndez Ayala

Styling by Nycole Sariol; Hair by Tanya Melendez; Make-up by Bo; Production by Aries Rising Projects

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Mariah Espada at mariah.espada@time.com