Oliver Jeffers still keeps a workspace in Brooklyn, where he lived for 17 years before returning to his native Belfast to be closer to family during the pandemic. When I meet the author and artist in his studio on a drizzly afternoon—a few hours before he’ll recite an original poem at a gala for the UN General Assembly—it’s awash in paint-splattered amusements. In one corner sits a ghost, a sheet with eyeholes that Jeffers proudly says glows in the dark and “really freaks people out.” On a ceiling-high chalkboard, written in his signature scrawl—a cross between a child’s handwriting and a ransom note—his list of tasks begins: “Glue moon.” Sure enough, on a large painted moon, he’s been testing out paper cutouts of astronauts from old books. There’s a can of Modelo beer by the sink, old wooden drawers whose labels read “Sorry cards” and “Library cards,” and every artistic instrument imaginable.

The scene is everything the mother of a 4-year-old Jeffers devotee could imagine, and then some. Jeffers, 44, best known for the nearly 20 picture books he’s both written and illustrated since 2004, and another 10-plus he’s illustrated, many of them best sellers and award winners, is a bedtime fixture in my house. In his work, he often balances his playful sensibility with serious topics. Earlier books constructed allegories around grief (The Heart and the Bottle) and friendship (Lost and Found). Recent ones have tackled capitalist greed and environmentalism (The Fate of Fausto) and walls (What We’ll Build).

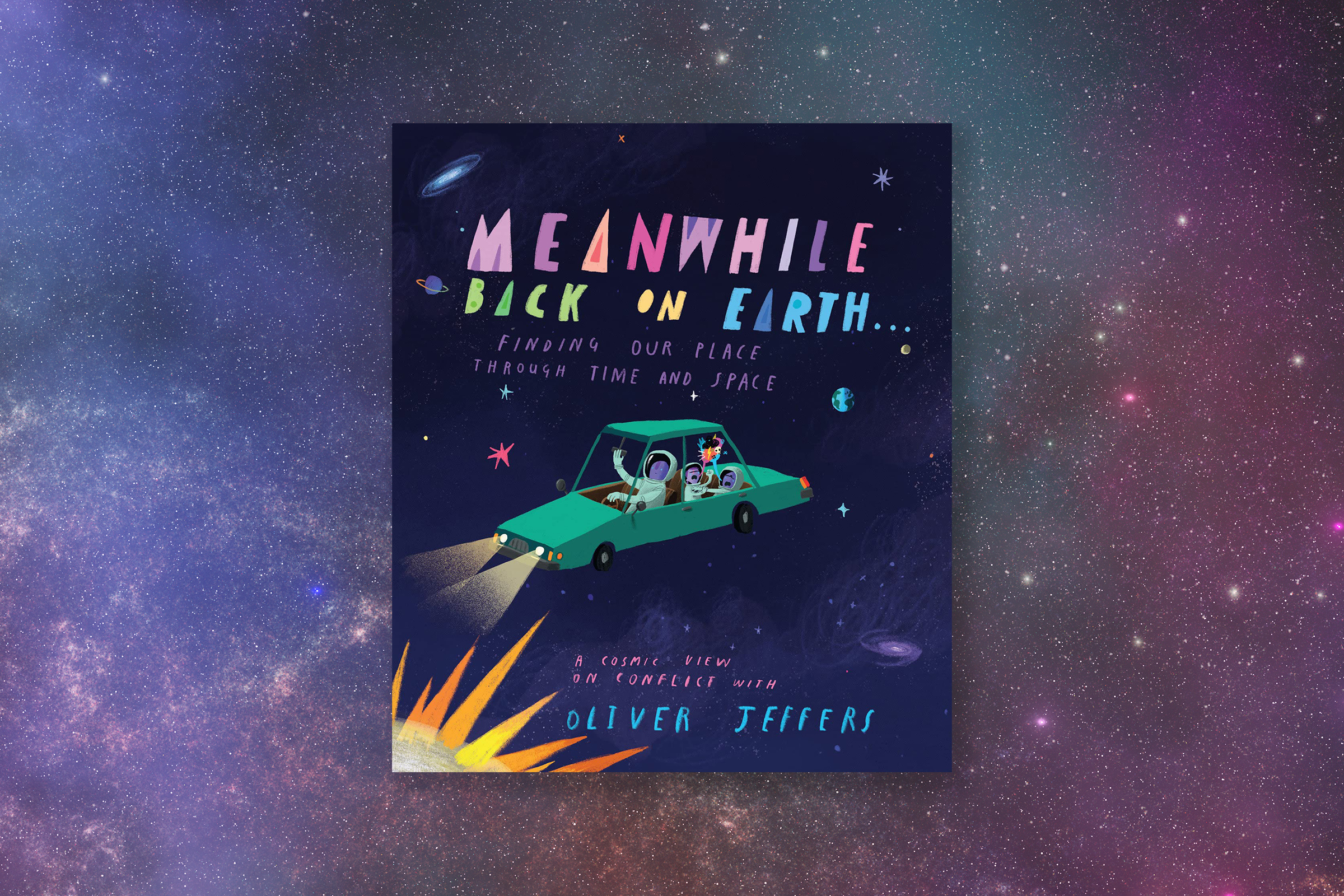

His latest, Meanwhile Back on Earth, coming Oct. 4, follows a Jeffers-like dad and his son and daughter through the solar system in a car turned spaceship. They look back on dark moments in history—wars, the devastating first encounters of colonization, cavemen fighting to survive. Images depicting tragic chapters are interspersed with those of the trio’s little green car, bickering siblings in the back seat. A dose of reality, a dash of whimsy.

Read more: The 10 Best YA and Children’s Books of 2021

In our conversation, I refer to Jeffers as a children’s book author, and he gently responds that he doesn’t see himself that way—he makes picture books. They’re primarily consumed by kids and parents, but not specifically intended for them. “It just so happens that most 5-year-olds share my sense of humor,” he says. But who’s got much use for boxes these days? When he went to COP26 in Glasgow last fall, none of the options for “profession” fit; whoever made his name tag chose “observer and translator,” which felt just right.

In 2017, Jeffers traveled to Nashville to witness a total eclipse of the sun. He recalls standing “in that path of totality and you’re suddenly looking at a black hole in the sky.” He felt the distance of 93 million miles the way you feel the distance to a tree or a house: “It buckled the knees from under me.”

Meanwhile Back on Earth channels this sense of perspective. Its subtitle is A Cosmic View on Conflict, and it has strong Lennon-esque “Imagine there’s no countries” vibes. It calls to mind Earthrise, the first photo of Earth taken from space, shot by astronaut William Anders during 1968’s Apollo 8 mission, which Jeffers suggests was perhaps less about exploring the moon than it was about looking back at the blue marble we live on.

The book was largely inspired by another experience Jeffers had looking at someplace familiar from a distance: his attempts to explain the conflicts of his native Northern Ireland to outsiders, beginning when he first came to the U.S. at age 11 on a summer camp scholarship to New York state. The Americans he met hardly knew the difference between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland, let alone why they were fighting. Decades later, shortly after his son was born, he watched news reports of violence in his hometown, flare-ups between Catholic and Protestant factions. “It’d be teenagers, 12-, 14-, 16-year-olds. What do they know? They’ve just been told a story,” he says. He looked at his newborn and thought about how he might use his particular talents to offer up a new narrative. “I don’t want to tell you that story,” he remembers thinking. ”I get to change the story.”

Storytelling, a deeply ingrained part of Irish culture, came naturally to Jeffers, much like his penchant for art. The two were intertwined as he grew up in a lively household with three brothers, a lot of cousins, and many nurses, doctors, and family members filing in and out to help because his mother had multiple sclerosis. He found that his talent for drawing had a pleasant effect: “Being in a big family and often ignored, I did whatever the hell I could to get some attention.” He began to specialize in art in secondary school, and as a fledgling artist a friend pointed out to him that his proclivity for creating series of paintings might lend itself to books.

As his bibliography grows longer, it’s also getting deeper. Sure, some of his books are just for fun—“I still need to entertain myself sometimes,” he says. But many of them wrestle with the very survival of humanity, and the many issues we keep failing to adequately face. He’s become increasingly aware of their interconnectedness. In interviews and discussions about the themes of his books, people have asked, “Is this book about the climate crisis?” and “Is this book about equality?” His answer: ”Well, yes. Everything is connected.”

Back in Jeffers’ Brooklyn studio hangs a small replica of a piano that appears to be on fire. It’s from a 2019 exhibit of his work inspired in part by a quote from Buckminster Fuller’s 1969 Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth. To paraphrase, Fuller writes that if you’re in a shipwreck, and a piano top comes along, it would make for a passable flotation device—but that does not mean it’s an optimal flotation device. The point is: when facing today’s global problems, we are clinging to yesterday’s solutions, despite our potential to do better.

This is what Jeffers is so galvanized by: if we could just see ourselves with a bit more perspective, see with clarity that the systems we’ve built aren’t working anymore, maybe we would be more compelled to try to change them. And he thinks that we can change them. It’s this belief he’s trying to champion in his work. And thank goodness, because what kind of picture books would result from someone who thinks we’re doomed?

But if we’re going to succeed, he says, we need to take a wider point of view, which brings him back to outer space and his latest book. “It’s this notion of the overview effect that happens when astronauts look at earth,” he says, “and are far enough to see that this is one giant, single system.”

A lot of people, when confronted with the unfathomable vastness of the universe, feel insignificant to the point of apathy, or even nihilism. Jeffers takes a different tack. “When people feel nihilistic, they haven’t finished that thought: if nothing matters, in a strange way, everything matters,” he says, the levity and optimism that make him a favorite of parents and kids everywhere shining through. So we should try to solve our problems, yes, but also have a little bit of fun while we’re at it. “The chances of being here at all are so infinitesimal. Why not just enjoy it as much as possible?”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Write to Eliza Berman at eliza.berman@time.com