Most years have at least a little something going for them, but 1968 was awful from the start. On just the 23rd day, North Korea seized the U.S.S. Pueblo, killing one sailor and holding the rest prisoner; on the 30th day, the start of the Vietnamese holiday of Tet, the Viet Cong launched a massive military offensive that cost more than 35,000 lives on both sides; on the 95th day, the Rev. Martin Luther King was murdered; on the 157th day, Senator Bobby Kennedy’s murder followed; on the 233rd day, Soviet army tanks crashed into Czechoslovakia; on the 241st day, the Democratic National Convention in Chicago descended into violence.

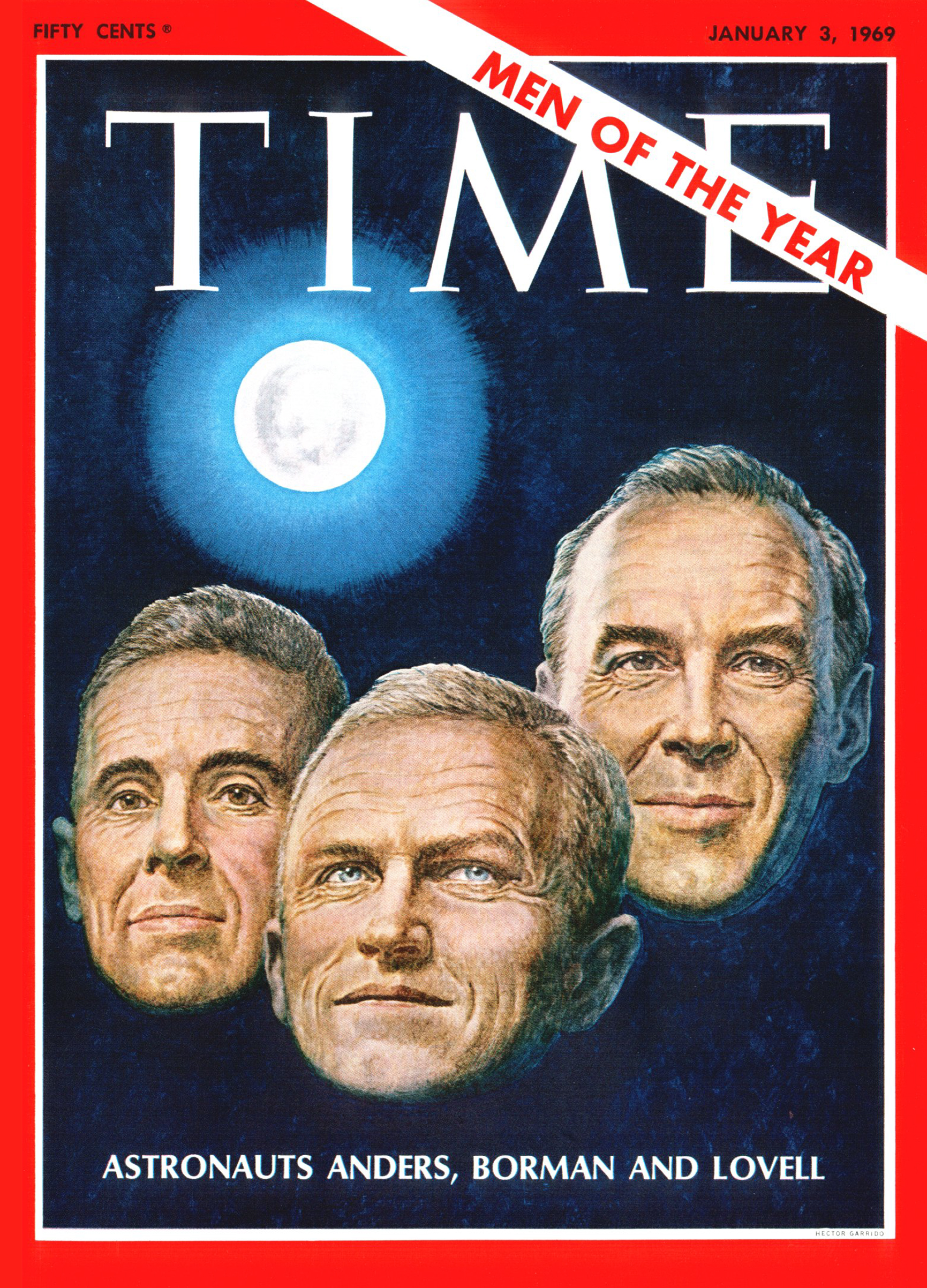

The year was shaped—and soaked in—the blood that was shed. And then, on the 359th day, there was poetry. Three days earlier, the crew of Apollo 8—Frank Borman, Jim Lovell and Bill Anders—had rocketed away from the mess at home and ventured out to the moon, becoming the first human beings to reach and orbit our closest celestial neighbor.

They arrived, as history would have it, on Christmas Eve. During the eighth of their 10 orbits, they pointed a TV camera out of one of their five windows and showed a global audience of 1 billion—nearly one of every three people alive—the grainy, flickery but undeniably otherworldly sight of the ancient lunar surface crawling by below their spacecraft. As that image played, Anders began reading: “In the beginning, God created the heaven and the earth,” and then handed off to his crewmates, who took turns reading further verses from Genesis—verses of renewal in a year of loss.

Borman, now 90, was the commander of the mission and is often said to have made the call to read from Scripture, but he describes it as a collaborative decision.

“I didn’t choose it,” he said this past October, when all three astronauts met with TIME to mark the 50th anniversary of their mission, at Chicago’s Museum of Science and Industry, where their spacecraft is displayed. “We all agreed it was the right thing to do.”

Half a century on, there are still lessons to be learned from the mission—about enterprise, about commitment, about how a shared undertaking larger than any individual can redeem, if not wholly heal, a fragmented nation.

As with so much about the early space program, part of what drove the decision to fly Apollo 8 was geopolitics. The U.S. and the Soviet Union had been in a footrace to the moon since cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first human being in space in 1961. In the summer of 1968, word began pinging across the intelligence web that the Soviets were going to skunk the Americans again.

“[Our flight was] going to be an Earth-orbital test of the lunar module,” says Lovell, also 90. “Instead we heard that the Russians were going to put a man or men around the moon by the end of 1968.”

So the decision was made in August that Apollo 8 should get there first, giving the crew and ground team just 16 weeks to figure out how to do it. Nobody had any illusions about how dicey a plan that was. Just the year before, the Apollo spacecraft had killed astronauts Gus Grissom, Ed White and Roger Chaffee in a launchpad fire before it had even made its first flight.

The Saturn V rocket that would be needed for a moon trip—a piece of ordnance so huge that if it blew up on the pad, it would produce a 2,500° fireball, 1,400 ft. in diameter—had had just two unmanned test flights. On the second one, it vibrated so badly, it nearly shook itself to pieces. That test would have made more news had it not occurred on April 4—the same 95th day of that ugly year as King’s assassination.

“Just four or five years before Apollo 8, they had the first test firing of the J-2 [upper-stage] engine,” says Borman. “And here we were riding a Saturn V to the moon. To me, it’s still a miracle that it went so well.”

Then too, there was a darker danger Apollo 8 faced. If the astronauts made it into lunar orbit but their engine failed to fire when it was time to leave, rescue would be impossible. They would circle the moon forever.

“You’ll ruin the moon for everyone,” one of the Apollo 8 wives was said to have warned Chris Kraft, NASA’s director of flight operations.

But the crew did go into orbit and they did come home, and in the process they gave the world yet another gift: the celebrated photograph that came to be known as Earthrise, which Anders captured as they came around the lunar far side on their third orbit. It illustrated, as nothing else had, the fragility of our planet, and is widely credited with helping to kick-start the environmental movement.

Even five decades later, Borman and Lovell, who were spaceflight veterans when they flew Apollo 8, continue to needle Anders, 85 now but the rookie of the crew then.

“I’m still trying to figure out who took that [picture],” says Borman, with a wink.

“Frank took it, I think,” Lovell answers.

“Bill took the picture,” Borman concedes.

“He didn’t want me to take it,” Anders mock-gripes, indicating Borman who, as commander, oversaw the picture-taking schedule.

When the crew splashed down in the Pacific on Dec. 27, it was clear that in the six days they’d been gone, a hinge in history had been turned. TIME was at that point considering its options for what was then known as the Man of the Year; the smart betting was that the choice would be Richard Nixon, who had been elected President the month before. But Nixon would be denied. A presidential election is quadrennial; Apollo 8 was epochal.

“It was elation, vindication, satisfaction, exaltation,” a TIME reporter in the Houston bureau wrote in a file he telexed to New York, describing the post-splashdown mood.

“There hasn’t been a night like this in the annals of space flight,” wrote another. “Within hours after splashdown, the staid and sober society surrounding the Manned Spacecraft Center came apart at the seams.”

So, in some ways, did the country. But unlike the first 361 days of the year, during which the national coming apart was an act of tearing, of rending, the 362nd day saw an exuberant bursting. “Thank you, Apollo 8. You saved 1968,” was the simple text of a telegram an unnamed American sent the crew.

That kind of collective joy—born of collective striving—can seem beyond us now. From the factory floor to the three men in the spacecraft, an estimated 400,000 people had a hand in making the lunar missions possible. Washington did its part too. The lunar program spanned four presidencies and eight Congresses, and while there was squabbling over scheduling and funding, there was bipartisan agreement that the larger mission would be seen through to the end.

The most recent four presidencies, by contrast, have seen America’s space goals change repeatedly: from the space station, to a return to the moon, to asteroid exploration, to Mars, to the moon again. That does not impress the old pioneers.

“NASA is banging around, hoping to get some direction, but mainly hoping to get some funding,” Anders says.

“You guys are wrong,” Borman laughs. “[Elon] Musk says we’re going to colonize Mars in the 2020s.”

The crew doesn’t dismiss the space entrepreneurs; indeed, they see them as part of an aviation tradition. “You had these nutty guys like Howard Hughes who invested their own money,” says Anders. “Some lost it, some made it. So you have to hand it to Musk.”

America could yet find its way back to the moon, either on public or private rockets. Nations do regain their sense of mission. The astronauts who made the long-ago journeys seem never to have lost theirs.

“I have never said it before publicly,” said Borman, with a clap on the knees of his crewmates as they sat together in Chicago, “but these two talented guys, I’m just proud that I was able to fly with them. It was a tough job done in four months, and we did a good job.”

And so heroes roll.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com