The cartoon has a king on his throne addressing a courtier. “I’m concerned about my legacy,” he says. “Kill the historians.” So, it might seem, it has come to pass.

How we record the past is currently headline news. In February 2020 Matthew Connelly of Columbia University wrote how under President Trump “vital information is actually being deleted or destroyed, so that no one—neither the press and government watchdogs today, nor historians tomorrow—will have a chance to see it.” And in the last two months we have learned that China’s President Xi Jinping plans to rewrite his country’s history and Russia’s President Vladimir Putin to liquidate the research group Memorial and its archives that document the Gulag prison camps.

What form of history should be taught is, of course, also a matter of intense debate in the U.S. The proponents of the 1619 Project argue for one version of America’s history, while another version is furiously defended by a huge—notably white, Evangelical, and/or Republican—section of the population, so that what is the past is now a vital political issue.

Yet such revisionism has itself a long history, going back at least to ancient Rome. Tacitus begins his Annals: “The histories of Tiberius and Caligula, of Claudius and Nero, were falsified, during their lifetime, out of dread—then, after their deaths, were composed under the influence of still festering hatreds.”

From the recounting of the Spanish Armada story (valiant small British ships against massive Spanish ones) to heroic tales of the battle of Britain, British history is crowded with myths. After 1945, the country exulted in tales of how the country had all pulled together valiantly during the world war, preserving Britain’s place as one of the Big Three powers—what the military historian Michael Howard has called “nursery history,” as sent up by the 1960s satirical revue Beyond the Fringe in its sketch “Aftermyth of War.”

Read more: Britain Can No Longer Hide Behind the Myth That Its Empire Was Benign

The French thought themselves the decisive factor in the outcome of the First World War; many in the United States have only a hazy notion of who helped them win the Second. Kwame Nkrumah, president of Ghana from 1960 to 1966, commissioned huge murals to show European scientists being instructed by African predecessors, a fiction he deemed necessary for national self-respect.

Hardly a single nation or country has not molded its history to advantage. The late-19th-century French historian Ernest Renan is famous for his statement that “forgetfulness” is “essential in the creation of a nation,” his positive gloss on Goethe’s blunt aphorism, “Patriotism corrupts history.” But this is why nationalism often views history as a threat. What governments declare to be true is one reality, the judgments of historians quite another. “History always emphasizes terminal events,” Albert Speer commented sharply to his American interrogators just after the end of the war. He hated the idea that what he saw as the earlier achievements of Hitler’s government would be eclipsed by its final disintegration.

Another case study can be found in Japan. Between December 1937 and January 1938, its army invaded China, going on a six-week rampage, massacring three hundred thousand civilians and raping more than twenty thousand women. (Both figures are Chinese estimates and are likely exaggerated, but since no records were kept, exact numbers are unknown.) There were other crimes committed over the next seven years, from the use of poison gas to the Bataan Death March.

But a postwar Japan not reconciled itself to such knowledge. Nationalist historians began to question whether the Nanjing Massacre ever happened, and in October 1999 an alternative textbook for schoolchildren, Kokumin no rekishi (The History of a Nation) was released, extolling Japan’s wartime record while vehemently attacking those who publicized its outrages. The founder of this faction, a 53-year-old professor of education named Nobukatsu Fujioka, declared that past events were not a fixed tabulation: “History is not just something that involves the discovery and interpretation of sources. It is also something that needs to be rewritten in accordance with the changing reality of the present.”

The Japanese historian Michiko Hasegawa has posed the question: “Why is it that people do not look at history honestly?” Her words invite an ironic response, given that Hasegawa argues that the atrocities committed by the Japanese military never occurred or at least have been greatly exaggerated. To this day, Japan has not prosecuted a single war criminal. From 1985 on, its prime ministers have made a point of visiting the Yasukuni Shrine in downtown Tokyo, where the remains of more than a thousand war criminals are buried, including fourteen Class A felons. Next door to the shrine is a museum that reiterates the revisionist view of Japan’s wartime history. The Nanking Massacre is referred to as “an incident”; history recedes into myth and becomes a form of propaganda. This is understandable, but also tragic.

One might argue that all wars require a heroic narrative, to inspire soldiers to risk their lives and, after the conflict has ended, to ensure that they and their survivors believe that they have not suffered or died in vain. However, such a comforting comes at great cost. As John Carey has said: “One of history’s most useful tasks is to bring home to us how keenly, honestly, and painfully, past generations pursued aims that now seem to us wrong or disgraceful.”

Without confronting the reality of what came before, however, that lesson goes unlearned.

Japan is not alone in having airbrushed its past, given that there is scarcely a nation that has not to some degree massaged accounts of its history. “I know it is the fashion to say that most of recorded history is lies anyway,” wrote George Orwell in 1942, reflecting on pro-Franco propaganda in the aftermath of the Spanish Civil War. “I am willing to believe that history is for the most part inaccurate and biased, but what is peculiar to our own age is the abandonment of the idea that history could be truthfully written.” The problem continued to trouble him. Three years later he went further: “Already there are countless people who would think it scandalous to falsify a scientific textbook, but would see nothing wrong in falsifying an historical fact.”

Read more: Putin’s War on Ukraine Shows the Dreadful Power of History

Thus the situation that Orwell satirized in Nineteen Eighty-Four with his vocabulary of state power and deception— Big Brother, Hate Week, Newspeak, doublethink, and the Thought Police: “The past was erased, the erasure was forgotten, the lie became the truth. . . . History has stopped. Nothing exists except an endless present in which the Party is always right.”

In June 2007, during a national televised conference of high-school teachers in Moscow, Putin grumbled about the confusion he saw in the way that Soviet history was taught and called for well-established criteria. He told the history teachers:

“As to some problematic pages in our history—yes, we’ve had them. But what state hasn’t? And we’ve had fewer of such pages than some other [states]. And ours were not as horrible as those of some others. Yes, we have had some terrible pages: let us remember the events beginning in 1937, let us not forget about them. But other countries have had no less, and even more. . . . All sorts of things happen in the history of every state. And we cannot allow ourselves to be saddled with guilt.”

Meanwhile, the battle for good history continues. As Francis Bacon famously said, truth is the daughter of time, not of authority.

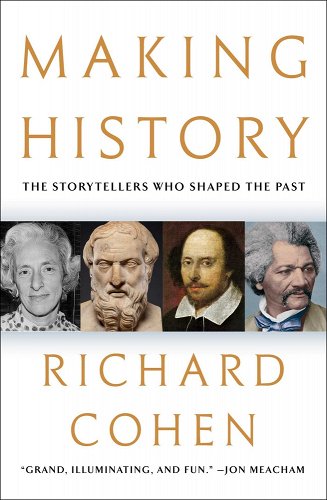

Copyright © 2022 by Narrative Tension, Inc.. From the forthcoming book MAKING HISTORY: The Storytellers Who Shaped the Past by Richard Cohen, to be published by Simon & Schuster, Inc. Printed by permission.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Breaking Down the 2024 Election Calendar

- How Nayib Bukele’s ‘Iron Fist’ Has Transformed El Salvador

- What if Ultra-Processed Foods Aren’t as Bad as You Think?

- How Ukraine Beat Russia in the Battle of the Black Sea

- Long COVID Looks Different in Kids

- How Project 2025 Would Jeopardize Americans’ Health

- What a $129 Frying Pan Says About America’s Eating Habits

- The 32 Most Anticipated Books of Fall 2024

Contact us at letters@time.com