Want a good, solid, rollicking laugh? Contemplate the end of the world—the whole existential shebang: the annihilation of civilization, the extinction of all species, the death of the entire Earthly biomass. Funny, right? Actually, yes—and arch and ironic and dark and smart, at least in the hands of Adam McKay (The Big Short, Vice), whose new film Don’t Look Up was released in theaters on Dec. 10 and is set to begin streaming on Netflix Dec. 24.

The premise of the film is equal parts broad, plausible and utterly terrifying. A comet measuring up to 9 km (5.6 mi.) across is discovered by Ph.D candidate Kate Dibiasky (Jennifer Lawrence), while she is conducting routine telescopic surveys searching for supernovae. Kudos and back-slaps from her colleagues follow—find a comet, after all, and you get to give it your name. But the good times stop when her adviser, Dr. Randall Mindy ((Leonardo DiCaprio), crunches the trajectory numbers and determines that Comet Dibiasky—which is about the same size as the asteroid that wiped out the dinosaurs 65 million years ago—is on course to collide with Earth in a planet-killing crack-up exactly six months and 14 days later.

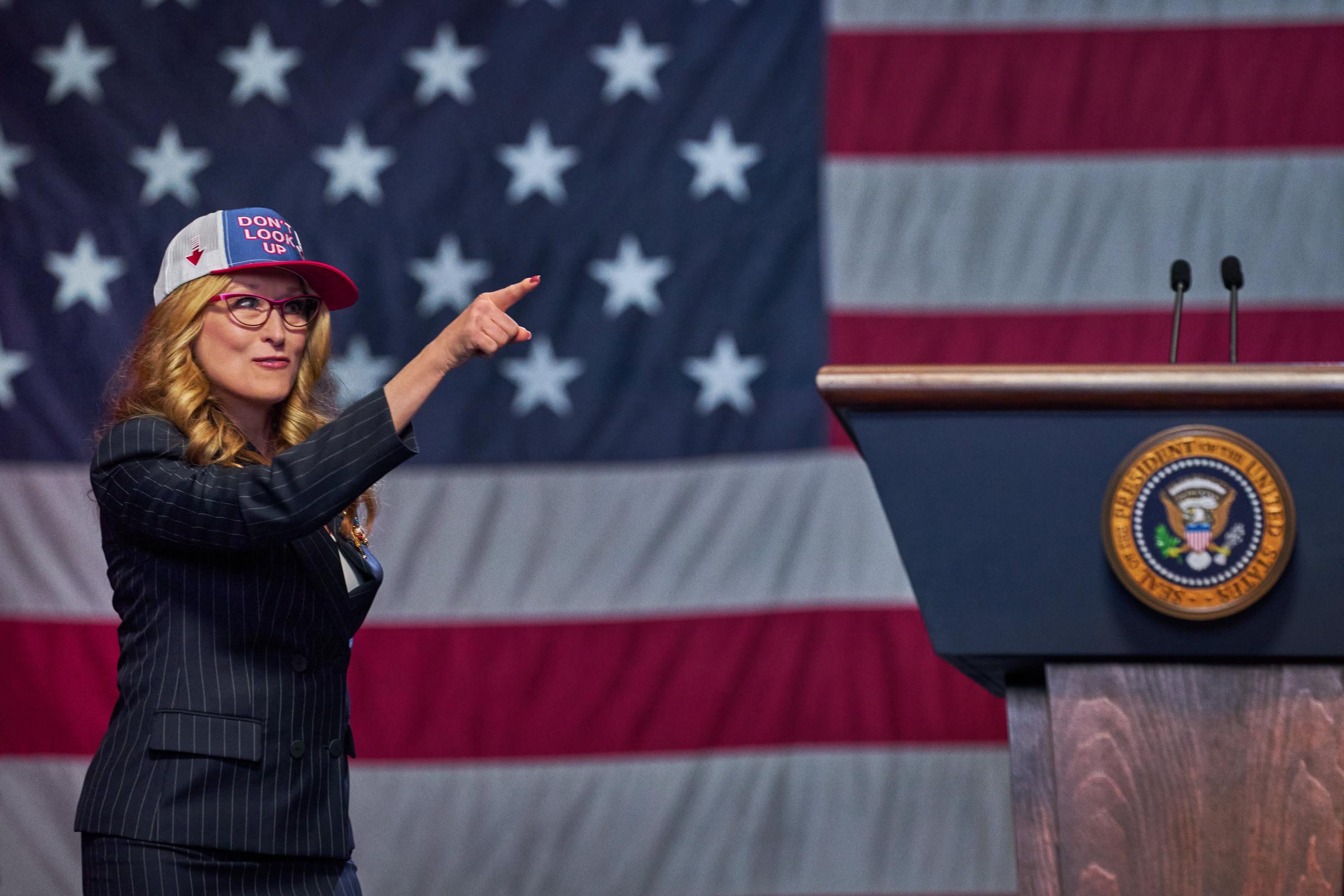

Mindy and Dibiasky bring the matter to the attention of the potty-mouthed, chain-smoking, deliciously corrupt President Orlean (Meryl Streep) and her pampered son and chief of staff Jason (Jonah Hill).

“I hear there’s a comet or an asteroid you don’t like the look of,” says Orlean, who is preoccupied with the upcoming midterms and her most recent Supreme Court nominee, who turns out to have been a former soft-core porn star. “What’s the ask here?”

“I’m so booored,” moans Jason, as Dr. Mindy tries to explain the science.

Rebuffed by the White House, the astronomers take their case to a morning cable show, The Daily Rip, but can’t get their message heard through the hosts’ incessant happy talk. The public responds with equal parts denial, conspiracy mongering and instant meme-making, declaring Dibiasky crazy and Dr. Mindy an AILF, with A standing for astronomer and ILF standing for, well, ILF. The president, meantime, is persuaded by Peter Isherwell (Mark Rylance), a Jobsian-Muskian-Zuckerbergian head of a technology company named Bash, that there is money to be made mining the comet for precious metals, distracting her from the more pressing business of just blowing the thing up.

For the planet and all life on it, the clock is ticking and there are mortal decisions to be made—decisions a frivolous, fractious, distracted humanity does not appear up to handling. There is an undertow of grimness to the story, one that could have dragged it under entirely if not for a hilariously absurd final scene. But the grim is there all the same—and that is very much the filmmakers’ apparent intent.

How real-life scientists monitor threats in the skies

Don’t Look Up is being widely seen as a climate change parable, with the same delay, debate and politicization of a simple, binary, life-or-death issue preventing the world from taking action. A strike from space is death by gunshot while climate change is a slow, global poisoning, but the result—the end of days—is the same. The key solutions for climate change are well-known by now—switching over from fossil fuels to clean renewables and retrofitting cities and other vulnerable places for the floods, wildfires, hurricanes and more that are increasingly resulting from the warming already baked into the system. It’s long-term planetary therapy as opposed to a fast cure. The solutions to the threat of incoming ordnance from space are less commonly discussed but could be equally and—more important, immediately—effective.

NASA, as Don’t Look Up reveals, already has a wonderfully named Planetary Defense Coordination Office (PDCO), whose remit is to scan the skies to discover and catalogue potentially menacing space rocks long before they can reach Earth, and help the government coordinate a response, either by deflecting or destroying the object. In the case of comets, there might be only so much time to muster a defense. Agglomerations of ice and rock that come barrelling towards us from beyond the orbit of Pluto, comets whip around the sun and then fly back out—moving at speeds that can top 70 km/sec (156,000 mph). They are not easily visible until they draw as close as the orbit of Jupiter, where outflowing energy from the sun fires them up and gives them their signature tail. Depending upon the size of the comet, the six months the world has to act in Don’t Look Up is not off the mark. Asteroids—which have little ice, no tails, and are not much more than space rubble—ply a smaller, less sweeping path around the sun and move more slowly than a comet. A rock that was discovered today might not intersect with the orbit of Earth—and threaten the planet—for a century.

“Our strategy is to find the population of objects out there of significant size, so we know where they all are,” says NASA’s planetary defense officer Lindley Johnson, who vetted an early draft of the Don’t Look Up screenplay more than two years ago. “Once we do that, it will give us decades of warning and we will then have the time to use whatever technology is available.”

When it comes to asteroids, just what constitutes “significant size” is something of a judgment call. In 2013, a 20 m. (66 ft.) asteroid exploded in the skies over Chelyabinsk, Russia as the drag of the atmosphere essentially ripped the rock apart before it could reach the ground. The blast damaged 7,200 buildings and injured about 1,500 people—though claimed no lives. That was scary but survivable. The asteroids that concern the PDCO most—and get the majority of their attention—are those measuring 140 meters or more.

“You work out the numbers from a sort of actuarial point of view,” says Amy Mainzer, professor of planetary science at the University of Arizona and a consultant on the film. “And 140 meters was the threshold that can cause a lot of damage.”

It’s not just size that makes a space rock a menace. It’s location, too. For a sufficiently large projectile to go from what NASA straightforwardly calls a near-Earth object (NEO) to a potentially hazardous asteroid (PHA) it must also intersect Earth’s orbit no further than 7.5 million km (4.65 million mi.) from the planet. That’s a whole lot of acreage by any common measure, but on the cosmic scale it’s a relatively near miss. Since 1998, when Congress began allocating funds to look for NEOs, NASA and astronomers from around the world have found 90% to 95% of the 1,000 or so one-kilometer or larger objects that are thought to be out there, but just 30% to 40% of the estimated 25,000 asteroids zipping about that are 140 meters or larger.

“It’s a really hard problem because the objects are small,” says Mainzer. “I mean, well, in astronomy terms they’re small. If one hits the Earth, it’s big.”

How to actually protect the Earth from an object hurtling toward it

What to do with an asteroid or comet of sufficient size that is on a death plunge toward our planet is another matter entirely. Nobody is really going to break up and mine the object—that plot turn was a cinematic confection for Don’t Look Up—especially a comet that gives Earth not years or decades to prepare, but months. Destroying it with explosives—and yes, even nuclear ones—is not off of the menu of options if time was short and the object was huge. But that would present problems of its own, since the giant rock would not be vaporized, but rather, shattered into a lot of smaller rocks.

“It’s hard to predict where all of those pieces are going,” says Johnson, “and it’s difficult to make sure that you’ve broken it into pieces small enough that Earth’s atmosphere can deal with it.” Still, if it’s duck a lot of small objects or go the way of life on Earth after the great collision 65 million years ago, there’s little doubt what humanity would do. “The dinosaurs,” says Johnson, “didn’t have a space program.”

Asteroids, which give us much more time to act, could be dealt with not by destruction, but deflection—slowing them down or altering their path just enough that they fly wide of Earth. On November 24, 2021, NASA launched the Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) spacecraft that will attempt to prove that this concept works. Its target is the asteroid Didymos (which poses no threat to Earth), a 780-meter rock that circles the sun in a path that takes it from just outside Earth’s orbit to just outside Mars’s. Didymos is itself orbited by a 160-meter moonlet named Dimorphos. When DART arrives at the Didymos system, it will deliberately crash into Dimorphos and scientists will then determine how much the speed and direction of its orbit have changed around its parent body.

It’s a small test on a small rock and does not mean the Earth is anywhere near having a robust planetary defense system in place, but as a proof-of-concept experiment showing that deflection can work, it’s an important first step. To help find asteroids that, unlike Didymos, might in fact pose a risk to us, NASA also plans to launch the Near Earth Object Surveyor spacecraft, which will go aloft in 2026, scanning the skies in our planetary neighborhood looking for anything suspicious. None of these solutions is perfect; all of them, however, can be of help.

Unlike climate change, which is the handiwork of humans, planetary bombardment is simply a risk of living in a busy, buzzing solar system. But like climate change, it is a problem we can mitigate—and even solve, provided we decide to take the necessary steps. In Hollywood’s latest yarn of the apocalypse, humanity plays dice with its very existence. In the world off the screen, we can choose differently.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com