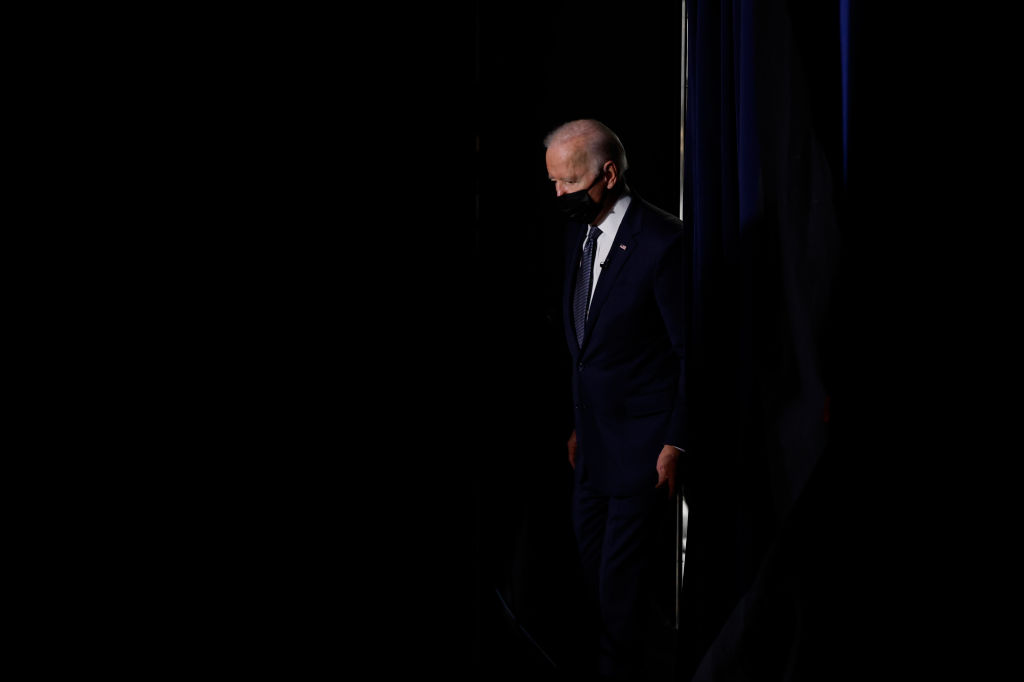

It was supposed to be in person, but the long tail of the COVID-19 pandemic meant Joe Biden’s first gathering of the world’s democracies would have to be held virtually. Opening the first day of meetings with heads of states of more than 100 countries that joined the Summit for Democracy, Biden walked onto a stage set inside the Eisenhower Executive Office Building in Washington and sat down at a wooden table with his Secretary of State Antony Blinken.

“Democracy needs champions,” Biden said, adding that the meeting had been on his mind for a long time.

Biden had promised to convene such a summit on the campaign trail while he was running against then President Donald Trump, who pressured federal judges, interfered in the Justice Department, used the tools of his office to campaign, and attempted to overturn legitimate election results. “Here in the United States, we know as well as anyone that renewing our democracy and strengthening our democratic institutions requires constant effort,” Biden said.

After the Cold War, the U.S. and world’s democracies were ascendent. The collapse of the Soviet Union was widely pitched as a verdict that authoritarian states not only sapped personal freedom but were proven to be forms of government that will fail. But in the last several years, as Trump acted on his undemocratic impulses and leaders in other democracies like India, the Philippines, Hungary, Poland and Brazil showed their own autocratic tendencies, the world has slowly awoken to the fact that maintaining robust democracies will take work.

“Democracy is in serious trouble. We’ve seen more and more democracies weakening their respect for political rights and civil liberties,” says Michael Abramowitz, president of Freedom House, which has rated countries on political rights and civil liberties since 1973. “It’s gonna take some time for us to dig out of the hole.”

During the two-day summit, which was widely seen as another way to build a broad and informal alliance against autocratic powers in Russia and China, leaders of countries have made commitments to fight corruption, support human rights advocates, bolster independent media and more clearly define and defend fair elections. The Biden Administration pledged to divert $424 million to help fund those efforts by civil society organizations and governments around the world. Many countries promised to return in a year and describe what actions they’ve taken.

But convening the summit has been a delicate balancing act for Biden. Instead of being able to present itself as a model democracy, the U.S. has become a test case for what it takes to push back against forces that would undermine the will of voters and take actions that disenfranchise citizens.

The U.S.’s autocratic rivals China and Russia relished the irony of the U.S. hosting a summit on democracy as its own system of government is going through such a tumultuous period. Beijing’s propaganda system kicked into gear in advance of the meetings, releasing a pair of reports calling China’s own authoritarian government a “democracy,” and describing the U.S. as a country where “money decides everything” and “political paralysis” hampers governing.

Russia’s foreign ministry said the U.S. shouldn’t be convening a summit and deciding who is a democracy and who is not. “It looks pathetic, given the state of democracy and human rights in the United States and in the West in general,” said Maria Zakharova, a spokeswoman for the Russian foreign ministry, according to Tass, Moscow’s state-run news agency.

The invitation list to Biden’s democracy summit was also a point of contention among human rights advocates. Biden was criticized for inviting Pakistan, which Freedom House rates as only “partly free” for intimidating media, curbing civil liberties and selectively enforcing laws. India, the world’s largest democracy, was also rated “partly free” in Freedom House’s 2021 report for discriminatory practices against its Muslim citizens and crackdowns on press and civil society. A Biden Administration official said the invitations to the summit were meant to represent a diversity of views and experiences and not designate which countries are healthy democracies and which are not.

Read more: Joe Biden’s Democracy Summit Is the Height of Hypocrisy

Democracy is not a “perfect end state,” says Rose Jackson, director of the democracy and tech initiative at the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab. “If the point of democracy is to course correct when things go wrong and have mechanisms to do that, then we actually have to be talking about the stuff that has been going wrong,” Jackson says. “We can have our flaws on display. Sometimes we are stronger when we acknowledge the flaws.”

Biden has repeatedly said during his presidency that he wants to show the country and the world that democratically elected political leaders can solve hard problems. He’s pointed to the recent enactment of a trillion dollar bipartisan infrastructure law as a sign that U.S. politicians from across the political spectrum can tackle issues.

But Biden has a lot of ground to make up. Under Trump, the global public soured on the U.S. as a model of democracy. General perceptions of the U.S. overseas rebounded strongly when Biden was elected, according to the Pew Research Center’s Global Attitudes Survey, but 57% of respondents in the Pew survey this spring agreed that the U.S. “used to be a good example, but has not been in recent years.” At home, Biden has promised to push for legislation to protect Americans’ right to vote from a wave of restrictions being passed by Republicans in state legislatures around the country, but the bills have languished in Congress as Democrats debate internally over a raft of social spending measures designed to reduce costs of health care and child care and address climate change.

Having forces inside the U.S.continuing to undermine democratic systems “makes it more challenging for the United States to try to have a summit like this,” Abramowitz says. The U.S. still has a vibrant media, strong rule of law and tradition, but Abramowitz points out that “there’s no question U.S. democracy has been backsliding” in recent years. “It’s very significant that the President has put a marker down,” Abramowitz says. “Now it’s time to show results.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com