On a Thursday afternoon in June, five months after Inauguration Day, I asked Tucker Carlson whether Joe Biden was the legitimately elected President of the United States.

This was halfway through a meandering phone conversation—me in my apartment in New York, he at his home in Maine—in which I spent most of the time trying to get a word in edgewise. Carlson paused. “What do you mean by ‘legitimately elected’?”

Did Biden win the election? I asked again.

“He did win the election,” Carlson said, his voice rising. “Do I think the election was fair? Obviously it wasn’t.” He ticked off a bunch of reasons he believed this: media bias, tech censorship of right-wing outlets, a shortage of voter-ID laws. I asked whether any of this resulted in determinative changes in vote counts, knowing that Donald Trump’s own Department of Homeland Security and Attorney General found no evidence of widespread fraud.

More from TIME

“Oh, I have no idea,” Carlson said, in an aw-shucks kind of way. “I’ve never said that. No one’s ever proved that. I don’t know if it’s provable.” But that was incidental to what seemed to be his larger point: “This weird insistence on pretending the election was fair when everyone knows that it wasn’t, even people who are happy about the outcome, is part of a much larger ritual that makes me very uncomfortable,” he said. “You’re required to say things that everyone knows aren’t true, but you’re punished if you don’t say them. It’s like a religious ritual.”

By this point, my head was spinning. This is Tuckerism in miniature: he sanitizes and legitimizes right-wing conspiratorial thinking, dodges when you try to nail him down on the specifics, then wraps it all in an argument about censorship and free speech. He has a way of talking about culture and politics that is rooted in defiance: defiance of elites, defiance of the federal government, defiance of scientific consensus. And it has won him the loyalty of millions of Americans who are already suspicious of everything he questions.

As of July, Tucker Carlson Tonight is the highest-rated show on cable, averaging about 3 million viewers a night, according to Nielsen, far outstripping his rivals who appear on CNN and MSNBC at the same time. In October of last year, Carlson had the highest monthly viewership of any show in cable-news history. He’s recently expanded into daytime TV, with Tucker Carlson Today on Fox Nation, the network’s digital streaming service. Seth Weathers, founder of BringAmmo.com, an online retailer that sells right-wing merchandise, reports that demand for Carlson-themed T-shirts and mugs has spiked: he’s already sold five times as much Carlson merchandise in 2021 as he did in 2020. “Our Tucker stuff is actually selling more than our Trump stuff,” he said.

Right now, Carlson may be the most powerful conservative in America. “No one carries more weight in Republican and conservative politics—no one—than Tucker Carlson,” said Jeff Roe, a Republican strategist who managed Ted Cruz’s 2016 presidential campaign. “He doesn’t react to the agenda, he drives the agenda. He’s the gold standard for Republican philosophy.”

Read more: The Conservative Case Against Banning Critical Race Theory

That “philosophy” is less of an ideology and more of a posture. Carlson has mastered the Trumpian mathematics of outrage—the more outlandish his rhetoric, the more vehement the backlash, the more formidable he becomes. Consider the controversies he has sparked and survived over the past four years. Carlson has referenced the white-supremacist “replacement” conspiracy theory—which claims elites are planning to replace white Christian voters with nonwhite immigrants—by name on his show, making him a hero to many white nationalists. He suggested that American “antiwhite mania” could lead to a situation comparable to the Rwandan genocide. He repeatedly argued—contrary to official findings—that George Floyd died of a drug overdose, then questioned Derek Chauvin’s conviction for Floyd’s murder. He has compared making kids wear masks outdoors to “child abuse.” Yet even as major brands like Disney and Lexus pulled millions of advertising dollars from his show, his hold on Fox’s conservative audience remained absolute. (A Fox News spokeswoman notes that as of the past quarter of this year, Carlson had 150 advertisers.)

Carlson is so influential that his show can even ruffle feathers in the upper echelons of the national-security establishment. He recently claimed that a “whistle-blower” inside the National Security Agency told him that his electronic communications were being monitored in order to take his show off the air (because, he said, he was attempting to set up an interview with Vladimir Putin). The allegation prompted an extremely rare denial from the tight-lipped agency, which called the claim “untrue.” (The Fox News spokeswoman pointed me toward a statement given to Axios: “We support any of our hosts pursuing interviews and stories free of government interference.”)

“He was sort of an untouchable,” according to Joseph Azam, a former executive at NewsCorp, another company in the Rupert Murdoch media empire, “because of the signal that touching him would send to the viewers that Fox never wants to lose. If you touch Tucker, you’re succumbing to the radical left. If you touch Tucker, you’re succumbing to cancel culture.” Azam left NewsCorp partly over differences around handling rhetoric like Carlson’s.

He has strengthened his hold on the conservative mind at a moment when most of the right’s elected leaders have been dethroned. The Senate’s top Republican, Mitch McConnell, has lost the GOP majority there, House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy is fumbling to corral a fragmented caucus, and Trump has lost both the White House and his social media megaphone. When I asked Carlson why Republicans had lost their grip on the federal government, he was unsparing. “First of all, they’re inept and bad at governing,” he said. “The party is much more effective as an oppositional force than it is as a governing party.”

Culture has supplanted policy as the central organizing principle of American conservatism, and Carlson has emerged as the leader of that oppositional force. His brand of grievance is considerably slicker than the former President’s but similar in its appeal to disparate corners of the conservative universe. He peddles conspiracy theories that thrill the paranoid base, economic populism to workers who feel ignored by billionaires, and anti-antiracism to whites who feel judged by progressive activists. But instead of Trumpian boasting, Carlson insists he’s just asking questions. What makes Carlson “awesome,” according to Turning Point USA founder Charlie Kirk, is that “he’s unafraid to kind of ask things that are on people’s minds that might be Orwellian thought crimes, that you’re not allowed to say and you’re not allowed to talk about.”

It has made him the top general in the war against Americans’ sense of shared reality. He throws kerosene on the controversies that divide the nation. He rejects science, history and even video evidence. Tuckerism is a mindset that gains its strength from perceived oppression, a voice that becomes louder the more you try to reason with it. Or as Carlson put it to me: “The truer something is, the more penalized you are for articulating it.”

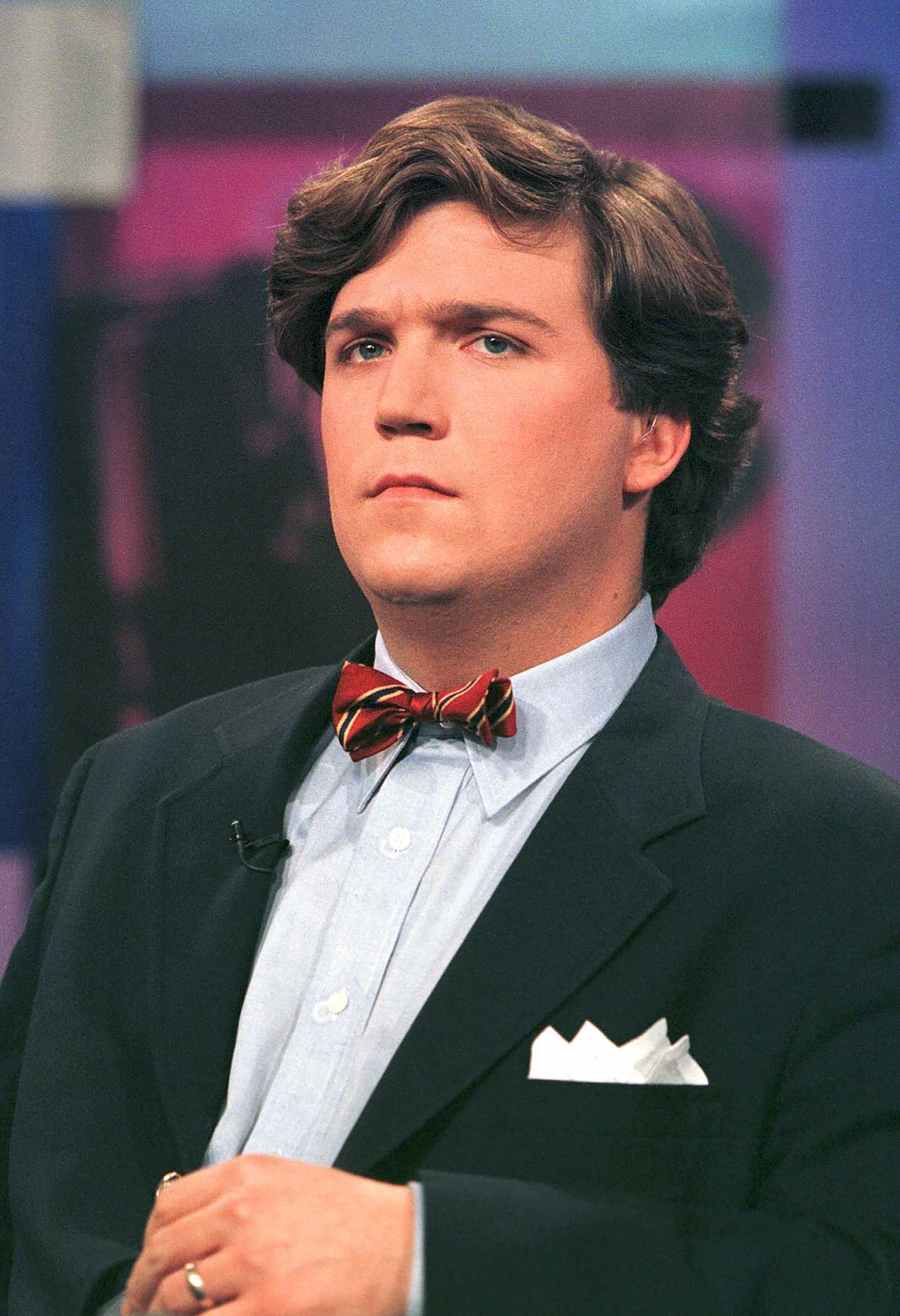

If you already love or despise him, there probably aren’t many biographical facts I can tell you about Carlson that you don’t already know. He is, at 52, the human embodiment of white contrarianism, the patron saint of golf dads. The details of Carlson’s winding journey through American media—how he married his high school sweetheart, how Jon Stewart once humiliated him on live TV, how he used to be a token conservative on CNN and MSNBC, how he co-founded the conservative website The Daily Caller, how he used to wear a bow tie but now doesn’t, how he used to drink but now doesn’t, how he used to follow conventional standards of journalistic practice but now doesn’t—have been exhaustively cataloged by fellow journalists who have spent years asking, “What happened to Tucker Carlson?”

What happened to Carlson is less important than what happened to the American right. The years since Carlson took over Bill O’Reilly’s coveted Fox News 8 p.m. slot in 2017 have been defined by few Republican policy wins but lots of drama. The Trump Administration was always more about grievance than governing. Now the crusades on the right have shifted even further from the political realm and into the cultural: from “free speech” to “cancel culture” to critical race theory (CRT). “The culture war—that is the new political war,” said Kirk. “It’s less about ‘Democrats bad and Republicans good,’ and it’s more like ‘What do we believe and why do we believe it?’”

What Carlson seems to believe is that anytime the “ruling class” agrees on something—that racism creates unfairness in American life, that masks and vaccines stop the spread of COVID-19, that Jan. 6 was an attempt to subvert the democratic process—you should suspect the opposite. To Carlson, objectivity is conformity, and conformity is cowardice. The more authoritative the facts, the more skeptical he becomes.

His rants sometimes have a grain of truth to them—more often than his critics would like to admit. Or, more specifically: there are kernels of fact within the miasma of misdirection. He does sometimes tell outright falsehoods—like his bizarre claim that “FBI operatives were organizing the attack on the Capitol”— but Carlson is often more careful than other right-wing hosts to avoid assertions that are factually disprovable, instead sticking to innuendo. While he never, for example, booked Trump’s fiction-spewing lawyer Sidney Powell on his show when she was making the rounds on Fox News last year, he did raise questions that fueled conspiratorial suspicions of an unfair election. “The people now telling us to stop asking questions about voting machines are the same ones who claim that our phones weren’t listening to us,” he said in a November segment. “They lie.”

And unlike many others in conservative media, Carlson was not a pure Trump booster. For all his pugnacity, Hannity rarely punches to the right, preferring to praise anybody wrapped in the cloak of MAGA. But Carlson projects a “pox on both houses” attitude that gives him credibility with his populist fan base. “Tucker is not afraid to wield power and hold Republican politicians accountable,” said a source who’s worked closely with him but who was not authorized to speak publicly. “Because of that, Republicans are wary of crossing Tucker.” According to Politico, Carlson told multiple people—perhaps jokingly—that he voted for Kanye West instead of Trump in 2020.

Carlson devoted portions of his 2018 book, Ship of Fools, to exploring how U.S. corporations have paid lip service to progressive ideas while continuing to ship jobs overseas. He has praised Democratic Senator Elizabeth Warren’s policies as “economic patriotism.” During our call, he made a compelling argument that elites have abandoned workers—one that would likely win nods from Americans on the left as well as the right.

But then just as quickly, he pivoted to argue that the “ruling class” had conspired to focus on racial inequality as a means to deflect from class inequality. “The way we’re thinking about these problems is false, and that’s by design,” he told me. “And the more time we spend arguing about Latin vs. Latinx, or whatever the f-ck it’s called, the less time we’re talking about the carried-interest loophole, or the 15,000 other ways that a tiny group of people are looting the country.”

Did he really believe American elites, most of them white, had hatched a plan for a reckoning on racial injustice as a way to increase their power? When I pressed him, he insisted he didn’t mean it was actually a “conspiracy.” Just, maybe, sort of one. “I think it was a conspiracy of shared interest and temperament,” he explained.

This distinction may be lost on some of his viewers. Much of his commentary traces a narrative similar to those you might read on QAnon message boards, minus the lurid fantasies of body doubles or child exploitation: Tuckerism is about resisting a shadowy group of elites conspiring against hardworking Americans, the corrupt establishment colluding to brainwash the masses, the plot to control what people think and say.

And viewers seem to interpret his rhetoric as legitimizing and spreading their thinking. After he name-checked the “replacement” conspiracy theory on his show, the anti-immigration website VDare called it “one of the best things Fox News has ever aired.” Andrew Anglin, founder of the neo-Nazi website the Daily Stormer, has called Carlson “literally our greatest ally.”

I asked Carlson if it bothered him that white supremacists seemed to love him so much. “I’ve never met a white supremacist in my entire life,” he said. “According to Joe Biden they’re everywhere,” he jokes. “Maybe I’m surrounded by them and don’t know about it.”

In 2020, Carlson’s former head writer Blake Neff resigned after his racist and sexist screeds on online message boards were revealed; Carlson addressed the scandal on air, saying it was “wrong to attack people for qualities they cannot control,” and the network condemned the posts as “horrendous and deeply offensive” in a statement. “I’m often accused of having those politics. Those are the opposite of my politics,” Carlson insisted to me. “I want a far less race-conscious America.”

But he seemed to be primarily outraged by the rhetoric condemning white supremacy. “The never-ending attacks on ‘white supremacists,’ ‘white nationalists,’ ‘white this,’ ‘white that’—what effect is that going to have?” he said. “I don’t want to live in a country where your race is the most important thing about you. That is a dead end. It never ends well.” This was shortly after President Biden had given a speech condemning racist violence on the 100th anniversary of the Tulsa massacre.

“If he got up there and said, you know, ‘The problem is the Blacks’ or ‘the Asians’ or ‘the Jews,’ we’d be like, ‘What! No! You can’t talk that way, that’s horrible.’ What effect is this gonna have on people?” he said, getting increasingly animated. “You think there won’t be a backlash to that? You think this isn’t making people radical in bad ways? Oh yes it is.”

Near the end of our call, I asked Carlson if he’d been vaccinated against COVID-19. He paused. “Because I’m a polite person, I’m not going to ask you any supervulgar personal questions like that.”

I told him he was welcome to ask me whatever he wanted.

“That’s like saying, ‘Do you have HIV?’” he said. “How about ‘None of your business’?” He broke into a cackle, like a hyena let loose in Brooks Brothers. “I mean, are you serious? What’s your favorite sexual position and when did you last engage in it?” (This has apparently become his go-to line when asked whether he’s been vaccinated; Carlson offered the same retort to Ben Smith of the New York Times.)

For someone who talks a lot about the right to ask questions, Carlson never did give me a straight answer. But he did find a way to drive the conversation back to his core theme: Elites are “censoring” conservative views and infringing on the people’s right to believe what they want. “I think there are systems in place that censor people for challenging the people in power,” he said. “It’s expressed as a kind of religious mania: Hunt down the heretics. How dare you defend Beethoven, or math, or Dr. Seuss, or whatever. But to focus on them is to miss the point, which is, this is no longer a free country.”

The resistance to people who “tell you what to say” is woven through many of his show’s segments, whether the topic is race, the coronavirus or the election outcome. It’s a rhetorical trick that allows him to attack anybody who disagrees with him as a mindless conformist. When Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Mark Milley—a burly white war veteran—testified in Congress that he thought it made sense to educate himself about CRT and was curious about the “white rage” that led to the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol, Carlson called him a “pig” and “stupid.” “Feed him a script and he will read it,” he said.

Carlson used to invite progressive guests on his show, if only to try to pummel them. Lately he’s mostly stuck to Republicans and right-wing provocateurs. “If I had to bet, most of this is performance for an audience,” said Christopher Hahn, a liberal pundit who appeared frequently on Carlson’s show until about two years ago. “I think that having lost shows in the past—like his show on CNN—probably has made him feel like ‘I’m going to stay relevant no matter what it takes.’”

Others say they once felt they could find common ground with Carlson, but no more. “I think he’s interested in propelling the propaganda that he wants to propel,” said New York City public advocate Jumaane Williams, a progressive who has appeared several times on Carlson’s show but not in recent years. “Truth is not particularly important to that.”

Unsurprisingly, the source who has worked with Carlson has a different explanation. “He recognizes that you have to be a survivor to be in TV. You can’t apologize in a society that doesn’t forgive,” the person said. “He knows this is the last time he’ll have a megaphone this big, so he wants to use it.”

That megaphone doesn’t seem to be going away anytime soon. “Tucker Carlson is an important voice in America which deeply resonates with millions of viewers,” said the Fox spokeswoman. “We fully support him.”

I asked Carlson why he thought his show occupied this unique space in the conservative ecosystem. “I wound up working at the last mass medium where you can say pretty much whatever you want, and that’s true, and I think my show is evidence that that’s true,” he said. “And they don’t ever tell you what to say.”

Despite speculation that he would make a formidable presidential contender, Carlson scoffs at the idea. “That seems like the unhappiest job you could have,” he said. “I just don’t have any ambitions like that. I have zero interest in being loved by people I don’t know.”

He didn’t have much to say when I asked whether he thought the 45th President should run again. “Oh, I don’t know,” he said, as if he was bored even thinking about it. Enthusiasm for Trump, he suggested, was really just about conservative “dissidents” wanting to be “protected” from the left. He pointed to the fact that the party didn’t bother to develop a policy platform for the 2020 presidential election as evidence that Republicans had abdicated their political responsibilities. “That’s disgraceful, in my opinion,” he said. “What’s the point in having a convention or a political party more broadly if you can’t be bothered to define what it is you stand for? I found that contemptible.”

Meanwhile, Carlson’s show has been the arena for the cultural combat exciting the right. The controversy over CRT, which has fueled right-wing activism on the state and local level, took off after researcher Christopher Rufo appeared on the show to argue that it had infiltrated the U.S. government. A frenzy over how race is taught in schools soon followed. According to the Washington Post, the anti-CRT organization No Left Turn in Education, which is dedicated to opposing antiracist education, saw its Facebook group jump from 200 page views to 1 million in the week after its leader appeared on Tucker Carlson Tonight.

Some critics, even on the right, say that Carlson is being cavalier about his influence. “He doesn’t understand his responsibility and the implication he has in actual people’s lives,” said Elle Kalisz, former vice president of communications for Gen Z GOP, a conservative youth group. “These aren’t just Fox News viewers. They aren’t just numbers. They are believing the absolute mess that Tucker Carlson is feeding them. And he knows, but he doesn’t take responsibility for that.”

Studies have suggested that Carlson has the ability to alter viewers’ behavior. Early in the pandemic—before he began arguing that the COVID-19 threat was overblown, before he called Biden’s mass-vaccination efforts “the biggest scandal of my lifetime”—Carlson was more concerned about the virus than Hannity and other Fox hosts. He even traveled to Mar-a-Lago to urge President Trump to take the outbreak more seriously. Researchers from Harvard and the University of Chicago found that during this period, Carlson viewers started changing their behavior—like washing their hands more frequently and canceling travel plans—three days earlier than the baseline Fox News viewers. Hannity viewers started changing their behavior four days later than the baseline. As a result, the researchers argue in a working paper, Carlson viewers started taking the pandemic seriously roughly a week before Hannity viewers did—a difference they say led to fewer cases and deaths in areas with higher Carlson viewership. (The Fox News spokeswoman pointed out that Hannity has since endorsed mask wearing, encouraged social distancing and said he planned to get the COVID-19 vaccine.)

The same researchers also suggest in a different working paper that Carlson’s show has a powerful effect on willingness to share anti-minority views. In February, they designed an experiment in which they gave conservatives the opportunity to tweet a petition to deport all Mexican immigrants. The participants were all shown a video of Carlson linking immigrants to serious crimes, but only some were allowed to say they had seen the segment before sharing the petition. Those who could refer to the Carlson video were roughly 33% more likely to want to share the petition. “Carlson is very good at providing excuses for people to express beliefs that they otherwise might feel uncomfortable with,” said Aakaash Rao, a Harvard researcher who co-authored the study. He can “legitimize views that were previously seen as extreme and bring them into the mainstream.”

Of course, Carlson disputes the notion that extremist views are more prevalent on the right than the left. When I asked him why, for example, 23% of Republicans believe in the QAnon conspiracy theory, he immediately responded with a Tuckerist whataboutism. “What percentage of primary-voting Democrats believe that you can change your biological sex just by wishing it so?” he asked. (Despite his purposely provocative description of trans people, Americans as a whole are becoming much more accepting; according to the Public Religion Research Institute, nearly two-thirds of all Americans and 47% of Republicans now say they’re “more supportive” of trans people than they were five years ago.)

“Not all the irrational people are on the left. There are irrational people on the right for sure,” he continued, twisting the premise of the question around itself. “But the idea that it’s the rational people vs. the irrational people is not actually true. If you think the main threat to America is white supremacy, when there’s not a single number that shows that’s even close to true, then you’re not rational.”

Here’s a single number: white supremacists and far-right militias were responsible for 66% of the domestic-terrorism threats in 2020, according to a study from the Center for Strategic and International Studies, and have been responsible for the most domestic-terrorism threats of any ideological group since 1994. I tried to make a point to that effect to Carlson; once again, I got derailed.

And round and round we went. Was Carlson repeating conspiracy theories, or was he creating them? Was he parroting the right-wing activists, or was he feeding them? The longer I talked to him, the harder it was to know. —With reporting by Simmone Shah, Mariah Espada and Nik Popli

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Charlotte Alter at charlotte.alter@time.com