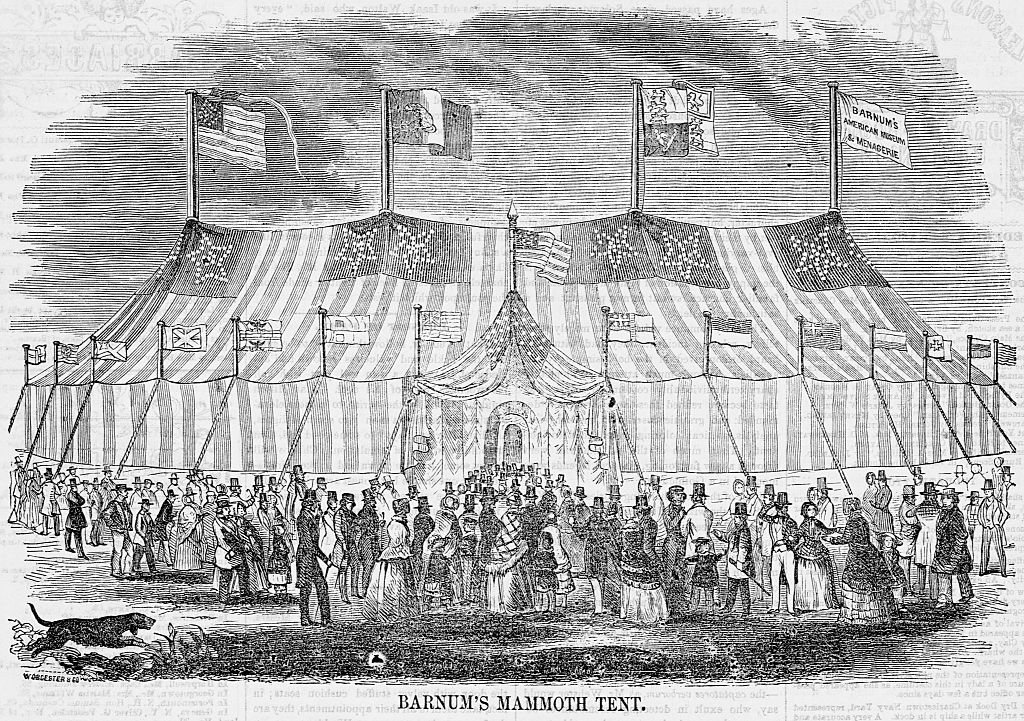

For the better part of a century—a period that encompassed the Civil War, America’s Gilded Age, WW I, and through the Great Depression—the circus reigned as far and away America’s premier form of popular entertainment. At the industry’s peak, the day the circus came town ranked with Thanksgiving, Christmas and the Fourth of July: banks and businesses closed, schools were dismissed, and an entire populace assembled on early morning main streets to watch the elephants and clowns and bejeweled entertainers parade from the train station to the circus grounds where the big top was raised to house thousands for afternoon and evening performances.

For most in attendance, it was an opportunity to see the impossible made real: aerialists, tightrope walkers, and equestrians performed superhuman feats; lion “tamers” turned their charges into obliging pussycats; elephants performed ballets by Balanchine; and the clowns were there to elicit laughter and compassion, bridging the gap between the incredible feats taking place in the rings and the awed onlookers in the stands. In an age before film and television, before professional sports and mammoth arenas, before PC monitors and cellphone screens, widely diverse audiences gathered under the canvas for a communal celebration of limitless possibility and a rare glimpse of a wider world of beauty, mystery and wonder.

Little wonder, then, that the circus had drawn the attention of the fabled showman P.T. Barnum, who had in the 1840’s amazed audiences around the world with his exhibitions of the diminutive Tom Thumb and introduced American audiences to songstress Jenny Lind, the “Swedish Nightingale.” For most of the final quarter of the 19th Century, Barnum, aligned with veteran circus man James A. Bailey, dominated the industry. But following the deaths of Barnum and Bailey, John Ringling and his brothers assumed control of Barnum & Bailey operations and would go on to form the behemoth of all circus-dom: The Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus, a.k.a. “The Greatest Show on Earth.”

For more than a decade after the merger of the two principals in 1906, the Ringling brothers toured the two shows separately, enjoying a virtual monopoly on plum dates and prime venues about the country and serving essentially as the impresarios for a nation. At the time that the United States entered WW I in 1917, the Ringling show employed about a thousand people and traveled about the country on 92 railroad cars, with the Barnum & Bailey show about the same size.

However, forces that would ultimately reshape the circus industry had begun to emerge. With so many workers and performers gone off to fight, the shows were for the first time in history lacking the personnel to stage full programs and move efficiently about. The Ringling show’s 250 canvasmen were reduced to 80, while the property men dropped from 80 to 20, most of them aging 4-F’s instead of the burly personnel who had swelled the ranks before the war. As for the cadre of grooms into whose care the show’s 335 horses were entrusted, it too had been decimated, for during World War I, a horse cavalry was still a vital component of the forces.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

Were all this not enough, in 1918 the Spanish flu epidemic, which would claim more than 22 million lives worldwide, swept through the United States, taking tens of thousands of lives and dragging down attendance at all public venues to levels that would not be experienced for more than a hundred years, with the onset of COVID-19. All these factors led the Ringling brothers—following the 1918 season—to make a momentous decision. Instead of returning the two big shows to their respective winter headquarters—the Ringling to Baraboo, Wisc., and Barnum & Bailey to Bridgeport, Conn.—all the properties were sent to the Connecticut facility. It was a decision not made lightly, for the Ringlings had begun their operations in rural Wisconsin, with five of the seven brothers, none outside their teens, drawing crowds of locals willing to pay 5 cents each to watch a bit of plate juggling, bareback riding of the family pony, and 6-year-old John Ringling’s efforts as a singing clown.

John Ringling had progressed from clowning to a role as the company’s business-meister, however, and to him the move was unavoidable. Not only would the administration and maintenance of a single operation be vastly more practical, but the tax burden in Connecticut was significantly lower than that in Wisconsin. And the truth was that in just a few short years, the circus had lost its virtual stranglehold on America’s choice for popular entertainment. Movies had matured from minutes-long diversions experienced in storefront nickelodeons to complex, full-length productions exhibited in comfortable theaters, including the first full-length features produced in Hollywood: The Squaw Man (1914) by Cecil B. DeMille and D. W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation (1915) and Intolerance (1916).

In addition, reaching the theaters where films and other more transitory entertainments could be enjoyed had become a vastly simplified endeavor for even the most remote farm family, owing to the ubiquity of the automobile. The first Model T Ford rolled off the assembly line in Detroit on Sept. 27, 1908. Less than 20 years later, the 15-millionth would follow. Americans would buy nearly 30 million cars and trucks in the years leading immediately up to the Great Depression, and it was estimated that by 1929 four out of five families owned a motor vehicle. Thus, John Ringling saw that combining the two big shows and confining their appearances to larger population centers only made sense for postwar America. And though many in Baraboo would never get over the loss of the circus, moving central operations to Connecticut, closer to major populations centers and transport lines, was the logical and inevitable choice.

If Ringling saw the move as anything other than a precursor to an even more grand and glorious future, he was not admitting it. Asked by an American magazine interviewer during the 1919 tour if the circus would ever be altered by progress, Ringling responded: “It never will be changed to any great extent, because men and women will always long to be young again. There is as much chance as Mother Goose or Andersen’s Fairy Tales going out of style.”

This article has been adapted from Battle for the Big Top: P.T. Barnum, James Bailey, John Ringling, and the Death-Defying Saga of the American Circus by Les Standiford. Copyright © 2021. Available from PublicAffairs, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com