Lakshmi Kuril woke up feeling unwell on April 27. A community healthcare worker in India’s western state of Maharashtra, Kuril, 35, had a pre-existing heart condition and the increased work and stress of fighting the COVID-19 surge that is ravaging India meant she often felt exhausted and lightheaded. But she didn’t let it stop her. “She wanted to be a doctor,” her husband Dinesh Kuril, tells TIME, but she grew up poor and “this was the closest she could get to that dream.”

After attending a meeting of fellow health workers, she felt worse and returned home—busying herself with housework and cooking dinner for her husband, her 15-year-old daughter and her 12-year-old son. As she stood to clear the dishes, she collapsed.

Dinesh rushed her to a nearby hospital, but was refused admission, possibly because there was no room due to a surge in COVID-19 patients—though Dinesh says the doctors “barely threw a glance” at Lakshmi. Unwilling to accept that Lakshmi was beyond help, Dinesh took her to another hospital 5 miles away. Doctors there said she arrived too late for them to save her. “I was so angry, helpless,” Dinesh says. “My wife sacrificed her life working for a government that did not care about her as a human being.” She was tested for COVID-19 after her death, though the results haven’t yet come through.

As a new wave of infections rips through India, many community health workers feel abandoned by a government that they say has consistently put their lives at risk with little protective equipment, little pay (sometimes just $30 a month) and little recognition. Lakshmi was an Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA), part of a 1 million-strong force of female health workers who serve as a connection between smaller, mostly rural communities and India’s overloaded public health system.

Experts warn the Indian government’s failure to support ASHA workers in the midst of a COVID-19 spike that is claiming thousands of lives a day is a public health risk of its own. “We need people to be tested, to be home-quarantining, and to be educated about where to seek healthcare. If we don’t have these individuals who are vital to that process, it creates another layer of insecurity,” says Dr. Amita Gupta, the deputy director of the Johns Hopkins University Center for Clinical Global Health Education. “We need to improve their livelihoods, because they function as a critical frontline workforce.”

‘Our lives don’t matter’

Since last year, ASHAs—who have traditionally worked with maternal and child health in their communities—have been the first defense against COVID-19 for many communities. During the first wave, they were instrumental in testing, tracing and arranging treatment for people with COVID-19.

Lakshmi’s death in Wardha, a district 400 miles northeast of Mumbai, has been a wakeup call for many of her fellow ASHA workers, who have long felt overlooked and unheard. “They say we are frontline workers, that we should be celebrated. But when we are sick they refuse us admission and leave us to die,” says Archana Ghugare, a friend of Lakshmi who is an ASHA in a nearby village. “It feels terrible to be treated this way—like we don’t matter, our lives don’t matter.”

Read More: India’s COVID-19 Crisis Is Spiraling Out of Control. It Didn’t Have to Be This Way

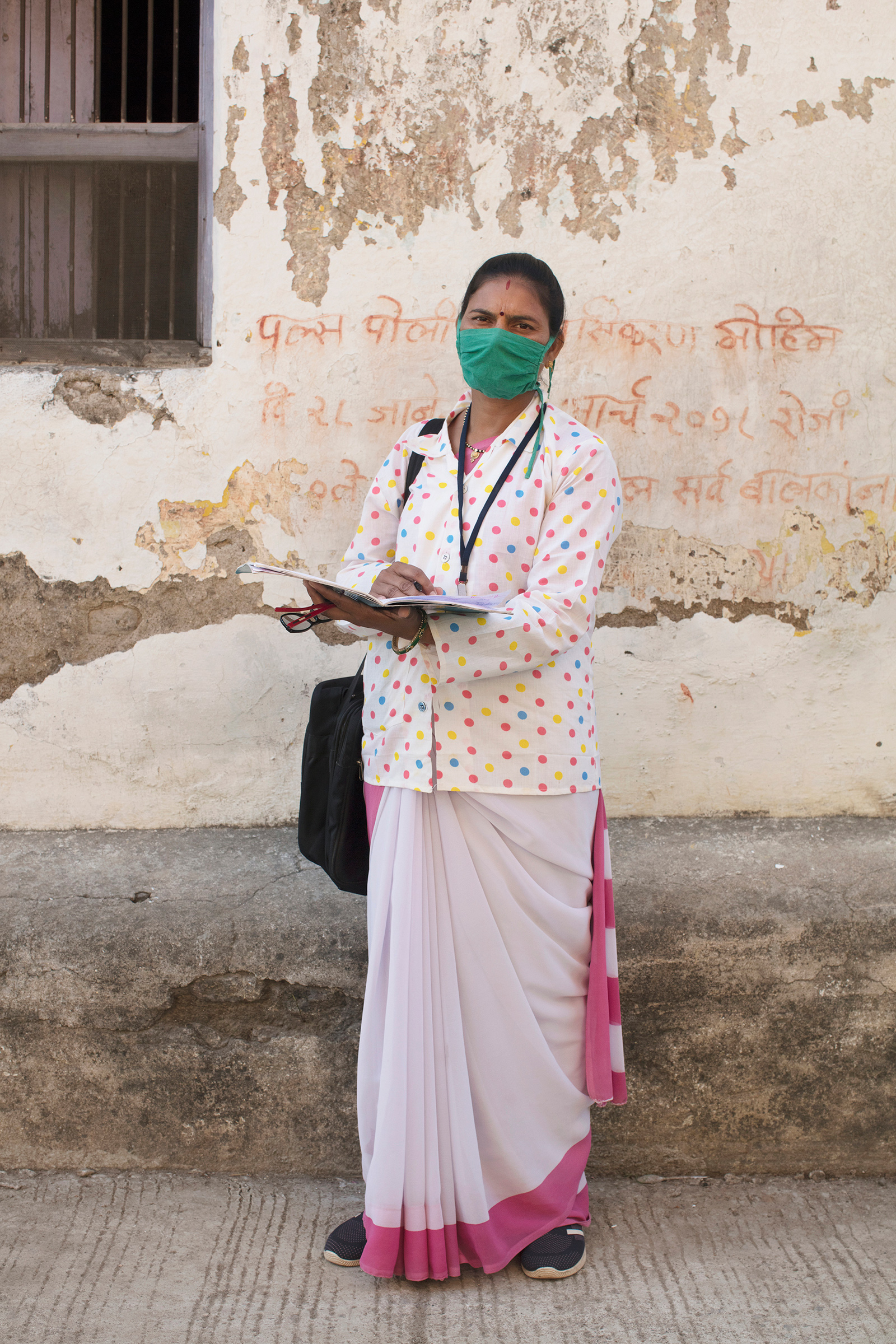

TIME first followed Ghugare in October last year as she rushed around her village helping to administer COVID-19 tests, dispel misinformation and educate her community about public health. Her voice catches when she thinks about her friend Lakshmi. “This is too close to our own lives—it could have been any of us.”

As of last September, 18 ASHAs had died fighting COVID-19, according to the government. In this latest, devastating surge, there are no definitive estimates on the number of ASHAs that have been infected by COVID-19, says Gupta. But the risks are clear. “ASHAs have been extremely vital to vaccinating and quarantining in rural areas,” Gupta says. “Having them come down with COVID infection leaves really major gaps in being able to respond effectively in rural areas.”

Fighting the pandemic without masks

Even before her friend’s death, Ghugare knew first hand her work was dangerous.

When Ghugare had asked her superiors for a mask at the start of India’s second wave, she was told she wouldn’t need one because she had received her first dose of vaccine. During the first major COVID-19 wave, the government gave ASHAs two masks per month, but “this time, nothing.”

Ghugare received the first dose of India’s homegrown vaccine, Covaxin, on Feb. 22. She delayed receiving the second dose of vaccine because she said she didn’t have the time or energy to walk the 5 miles to the clinic. “I could have taken an auto rickshaw but that’s too expensive at 50 rupees [$0.69],” she says. “We don’t get paid so much to afford an auto ride to the vaccination center.” The average salary of an ASHA is $30 to 40 a month, but it can be higher depending on incentives offered by different state governments.

On April 17, she tested positive for COVID-19. Initially, she was not scared, but as the COVID-19 cases skyrocketed across the country and she witnessed people pleading for hospital beds and oxygen and saw news reports of bodies piling up in crematoriums, she began to feel uneasy. And then Lakshmi Kuril died. “I am now petrified,” she says.

Ghugare’s own case of COVID-19 turned out to be mild. But even on leave from her job for 21 days, quarantined at home, she still makes sure to call her patients every day to advise them. “I feel responsible for them,” she says. “I need to stay with them through this ordeal.”

Read More: The Survivor’s Guilt of Watching India’s COVID-19 Catastrophe Unfold From Afar

ASHA workers want the government to supply them with masks and protective equipment that other medical workers who are in close contact with COVID-19 patients receive. A survey by Oxfam India, reported by the Indian media last September—showed that only 75% of ASHA workers were given masks and only 62% were given gloves. ASHA workers interviewed by TIME say they have even less access to masks, gloves and sanitizer now than during the first COVID-19 wave last year.

Also troubling to many ASHAs is that a government life insurance scheme for health workers expired in March—meaning they are fighting the pandemic without assurances that their families will be supported if they die. The health ministry, in a tweet on April 18, had said it was working to finalize a different insurance plan for the health workers.

COVID-19 overwhelms villages and small communities

Despite the risks, ASHA workers say their only option is to continue to work because their communities are in such dire need. And like experts, many warn that official COVID-19 counts—which have peaked at more than 400,000 cases a day—don’t come close to telling the true story.

“There was not a single case in my village last time,” says Kanchan Pandey, an ASHA from a village in the northeastern state of Uttar Pradesh. “But this time there are already 5-6 active cases and as people keep coming from cities and there are no quarantine centers, the cases will rise even more.”

In Ghugare’s village there are officially just 200 cases. But if testing was ramped up “the number of cases will be much higher,” she says.

In low-income areas in cities, newer hotspots are emerging. “Every second home is affected this time,” says Usha Thakur, an ASHA from Najafgarh, a city outside New Delhi. “There are four to five people affected in the same house. But the lists are being updated with only one name from one house. “

She adds: “Last time, we were under tremendous pressure to test, test, test. This time not so much.”

And the pressure on ASHAs, who are the only health resource in many of the communities they serve is immense. “My phone rings through days and nights,” Thakur says. “I have been overwhelmed. And sometimes I do not know how to handle it…. All I know is that I will try to save as many lives as I can with my limited resources.”

Lakshmi Kuril’s husband blames this stress for his wife’s death. Despite having been diagnosed with a congenital heart condition,“she worked day and night—walked in the heat to different centers as and when assigned,” Dinesh says.

He says Lakshmi would come back home tired and exhausted and grumble that her job was going to be the death of her. “And look what happened?” he says, breaking down into tears. “Today it’s my wife, tomorrow it will be another ASHA. This is not right—someone needs to intervene. Someone needs to stop this injustice.”

With reporting by Billy Perrigo / London

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com