Just before noon on Jan. 20, Joseph Robinette Biden jr. put his hand on a bible and vowed to uphold the Constitution as the 46th President of the United States.

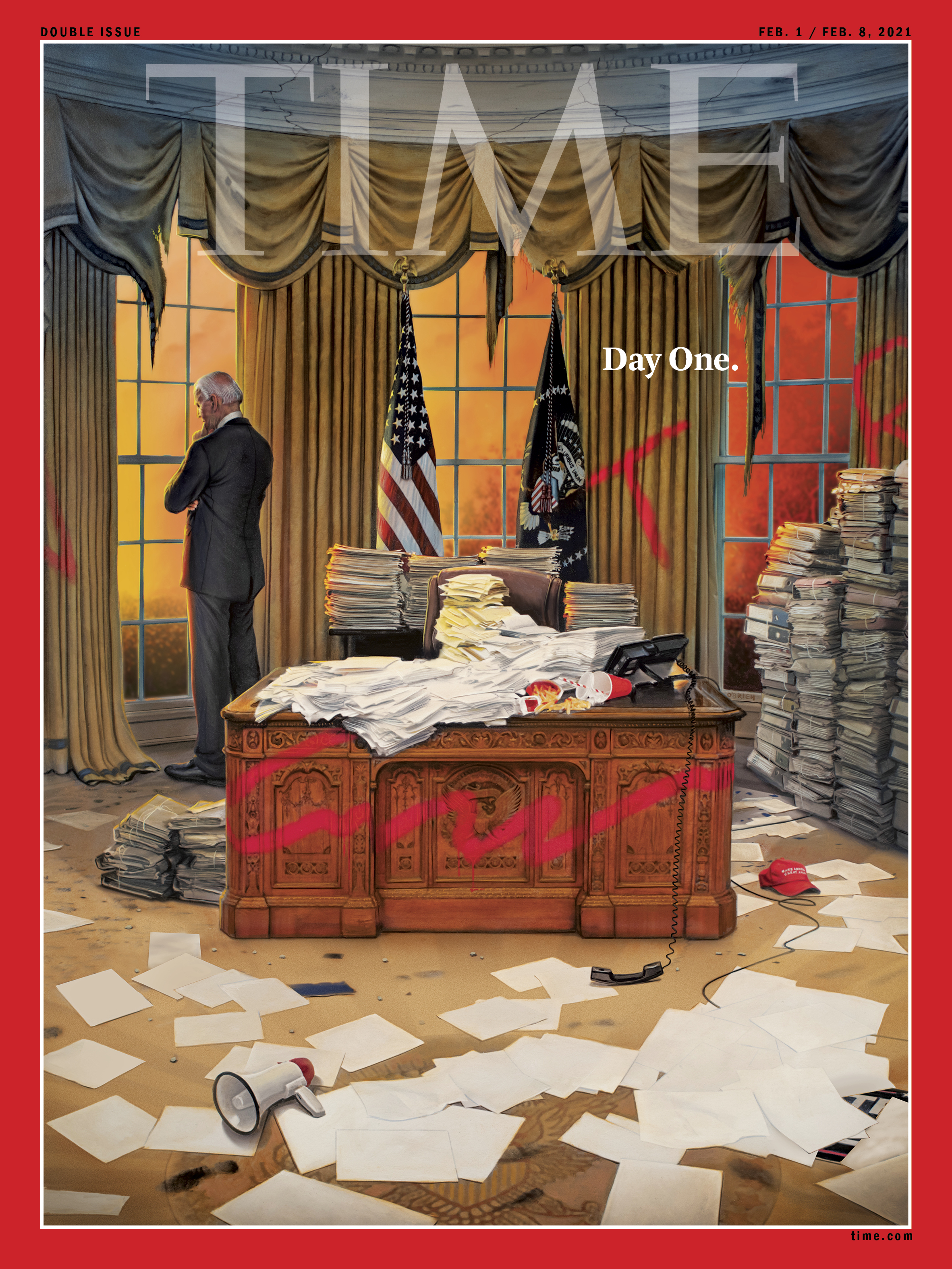

It was a first step toward restoring a semblance of normalcy to a shaken democracy. His predecessor, after two months of trying to stay in power by overturning the people’s will, told the American people to “have a good life” before skipping the ceremony. The National Mall was nearly empty, cleared of crowds because of the threat of violence. Biden’s words rang out over a capital under lockdown, fortified by some 25,000 National Guardsmen. It felt like a wartime Inauguration.

“We must end this uncivil war,” said the new President, “that pits red against blue, rural vs. urban, conservative vs. liberal.”

Biden stood on the West Front of the Capitol, a building that two weeks earlier had been invaded for the first time since the War of 1812. He was flanked by members of Congress who had spent that day fleeing the armed mob that desecrated the citadel of democracy with the encouragement of Donald Trump, breaking windows, destroying artifacts, smearing blood on the marble. “We’ve learned again that democracy is precious, democracy is fragile,” Biden said. “And at this hour, my friends, democracy has prevailed.”

But only barely. Biden now leads a country divided between Americans who believe in facts and Americans who distrust them, between those who want a multiracial Republic and those who seek to invalidate nonwhite votes, between those with faith in democratic institutions and those who put faith only in Trump.

A democracy is only as strong as the faith of its participants. At the very least, that faith must be rooted in some sense of shared reality, a willingness to agree to disagree according to the laws laid out in the Constitution. At the dawn of Biden’s presidency, when millions of Republicans believe the false conspiracy theory that the election was stolen, and thousands turned to violence to “stop the steal,” even that simple foundation seems wobbly. Biden seeks to unite a country whose differences are not political but epistemological. “The people who already believe that the election was stolen and that Joe Biden isn’t a legitimate President, I don’t know if there’s anything we can say to them,” says Whitney Phillips, an associate professor of communications and disinformation at Syracuse University. “That would require these believers to completely reconfigure their sense of self and their identity.”

The Civil War historian Eric Foner says this moment reminds him less of the start of that conflict and more of the end of the postwar Reconstruction, a bloody period of armed insurrection and racial terror. Trump’s refusal to accept the outcome of the election resembles the “Lost Cause” narrative, in which white Southerners romanticized their defeat, telling themselves, “‘We lost, but really, we won,'” Foner explains. “Things happen that you don’t like. You’ve got to find somebody to blame, so you glorify the loss.” The narrative of the Lost Cause provided the emotional underpinnings of more than a century of white-supremacist glorification that endures to this day; it’s no coincidence that at least one of the rioters was waving a Confederate flag.

The siege at the Capitol may be the start of a similar period of division sharpened by delusion. How Biden handles it will help determine his legacy. Uniting a nation this fractured may be beyond the powers of any American President. Yet if Trump could use the presidency to undermine the foundational consensus of our nation, Biden is betting he can use the same bully pulpit to rebuild it. He spoke of the “better angels” of American democracy surviving Civil War and World Wars, the Great Depression and 9/11. “In each of these moments, enough of us have come together to carry all of us forward, and we can do that now,” the new President said. “History, faith and reason show the way.”

It may be harder than Biden thinks. Watching the mob storm the Capitol, I was reminded of a Trump protest I’d covered in September, outside a Biden campaign event in Warren, Mich. As Biden spoke, a scrawny man in his 60s looked me straight in the eye and said that if Democrats won the election, “We will eliminate them.”

He told me his name was Mark. “If they win, the American people are going to personally, bodily remove them from office,” he repeated. “Bare hands. Go.”

I asked if he planned to join this violence. Mark said he usually was more of “a guy that stands by and watches,” but that could easily change. “If I was told, ‘Hey, you got to do or die,’ I’m there,” he said.

Over the next six months, Trump and his enablers in the GOP told people like Mark that the stakes were, in fact, “do or die.” They fed the conspiracy-addled base more and more lies to inspire more and more devotion. It was this mass delusion, not the facts of the election, that motivated GOP lawmakers to object to the certification of Biden’s victory. The faith of the voters demanded it, explained Senator Ted Cruz as he claimed (inaccurately) that 39% of the nation thinks the election was rigged. “You may not agree with that assessment,” Cruz said, “but it’s nonetheless a reality for nearly half the country.”

Biden addressed the reality gap head-on. “Recent weeks and months have taught us a painful lesson: there is truth, and there are lies,” he said. “Lies told for power and for profit.” He called on fellow leaders to “defend the truth, and defeat the lies.”

Faced with such rampant and cynical senselessness, the word unity seems to have lost its meaning. House Republicans pleaded for “unity” as they voted against impeaching Trump; to them, unity meant something closer to political impunity. When Biden calls for unity, he envisions bipartisan collaboration, a kind of peace through process. For some on the left, unity is achieved through change. “Unity is policy,” says Nelini Stamp, director of strategy and partnerships for the Working Families Party. “If you satisfy people’s economic needs and the racial inequities, there will still be divides, but it would go much further toward unity than just words.”

Unity is not the same as uniform opinion or even widespread agreement. By those standards, the United States of America has rarely been unified, and never for long. Our deep divisions date from the original sin of chattel slavery. White supremacists, conspiracy theorists and right-wing militias have stalked American history, from the Ku Klux Klan to the John Birch Society to the Oklahoma City bombing. Even achievements that now unite us were divisive in their time. Most Americans opposed intervening in World War II after the Nazis swept across Europe, most Americans disapproved of the civil rights movement as it was happening, and the space race was controversial because of its high price tag. Disunity is as American as putting a man on the moon.

Biden realizes this. “Every disagreement doesn’t have to be cause for total war,” he said in his Inaugural Address. “And we must reject the culture in which facts themselves are manipulated and even manufactured.” But the 46th President now must lead a vast swath of the electorate that has declared its allegiance not to a particular party or political creed but rather to a single individual–a scenario the founders feared so much they designed a system of checks and balances to prevent it from defeating their experiment in self-government.

Many Trump voters, of course, did stand up for the rule of law in the bitter aftermath of the election: the Republican lawmakers who certified the result in their states; the local officials who refused to bend to Trump’s pressure; the conservative judges who threw out baseless lawsuits; the GOP members of Congress who risked their political futures to vote for his impeachment. Many received death threats in response. “I got one around my birthday in the middle of November that said, ‘Enjoy your last cake,'” recalls Georgia GOP election official Gabriel Sterling, who repeatedly shot down Trump’s false claims of election fraud. U.S. District Judge Matthew Brann, a conservative who dismissed Trump’s legal attempt to invalidate nearly 7 million votes cast in Pennsylvania, says he got threats “that would make a sailor blush.” At least one GOP lawmaker who voted to impeach Trump for inciting the mob bought body armor to protect himself.

But Biden’s inauguration marked a turning of the page. If Trump’s rhetoric invited conspiracy theorists and white supremacists into the middle of the political arena, Biden has wagered his presidency on an ability to banish them to the fringes, and to restore a sense of calm and decency, if not total agreement. “Hear me clearly: disagreement must not lead to disunion,” he said. “I pledge this to you: I will be President for all Americans. And I promise you, I will fight as hard for those who did not support me as for those who did.”

Although the nation braced for violence, Biden took the oath without interruption. Speaking from the site of a violent insurrection, he argued the events of recent weeks had vindicated the strength of American institutions–a message he sought to project to the world. “America has been tested,” he said from the Capitol steps. “And we’ve come out stronger for it.

But unity will require more than agreeing not to overthrow elections. It will require convincing Americans in the throes of Trumpism to stop thinking of their political opponents as their enemy.

For Republicans like Glenn Centolanza, the attack on the Capitol was a breaking point. Centolanza, 63, owns a limo business in Bensalem, Pa. Normally it works up to 600 weddings a year, but COVID-19 canceled almost all of them. A couple of weeks ago, a woman called looking for a ride to Washington on Jan. 6. “She said, ‘Are you for Trump or against us?'” Centolanza recalls.

Centolanza voted twice for Trump but had since grown disillusioned by his lies. “I’m a Republican with common sense and a heart,” he says. “I don’t believe the Kool-Aid with Trump, but I thought he was 80% right until the last two months.” Since he was driving clients to D.C. anyway, he figured he’d go and see Trump speak.

At first, it seemed like a rally full of peaceful protesters who were just as mad as he was. “My business is upside down, the world is upside down, I’m not happy about anything,” Centolanza says. When Trump urged the crowd to march to the Capitol, Centolanza joined them. Along the way, he saw two rough-looking guys screaming about “taking our country back.” At the steps of the Capitol, the two men started to push at the police barricade, confronting the officers guarding the building. One of them turned to face the people behind them, Centolanza recalls, “and said, ‘If you’re not willing to die here today or go to jail, you have to leave.'”

That was enough for Centolanza. “I turned and started to walk backward,” he recalls.

Joe Biden may never unify America. That may not even be possible in a nation so riven by disinformation and delusion. But if he can get Americans who disagree on everything else to agree on the democratic process, if he can help restore political debate to the realm of truth, if he can deliver enough solutions to restore some small faith in government, that would be a start. America still won’t be united, but it could be united enough. The retreat of Glenn Centolanza is a place to start. He says he plans to give Biden a chance. “I didn’t hate Joe Biden,” he says. “I like him. I’m gonna give him the benefit of the doubt.”

With reporting by Julia Zorthian

Correction, January 21:

The original version of this story misstated Gabriel Sterling’s last name. It is Sterling, not Sperling.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Charlotte Alter at charlotte.alter@time.com