When the count of Georgia votes for former Vice President Joe Biden overtook those for incumbent President Donald Trump on Friday, Nov. 6, the congratulations that began rolling in weren’t directed at Biden’s camp alone. They also went to Stacey Abrams, the former Minority Leader of the Georgia House of Representatives who, after a failed race as a Democratic gubernatorial candidate in 2018, began a massive voter registration effort in a state that’s been voting for Republican presidential candidates for nearly three decades.

In this year’s election, 1.2 million African Americans in Georgia voted, up from 500,000 in the 2016 election, according to the Georgia Legislative Black Caucus. As the state has grown more diverse over the last decade, Black turnout helped make the state’s historically-close election trend toward Biden. Some credit for that leap has gone to the organizers in Georgia who helped register more than 800,000 new voters since Abrams lost the governor’s race; of those registered to vote after Nov. 2018, about half are people of color and 45% are under 30—both demographics that tend to lean Democrat.

Social media users, and Abrams herself, were quick to point out that she did not work alone. In particular, there were many Black women—such as advocates Nsé Ufot, Helen Butler, Deborah Scott and Tamieka Atkins—involved in Democratic voter registration and motivation efforts in the still too-close-to-call state.

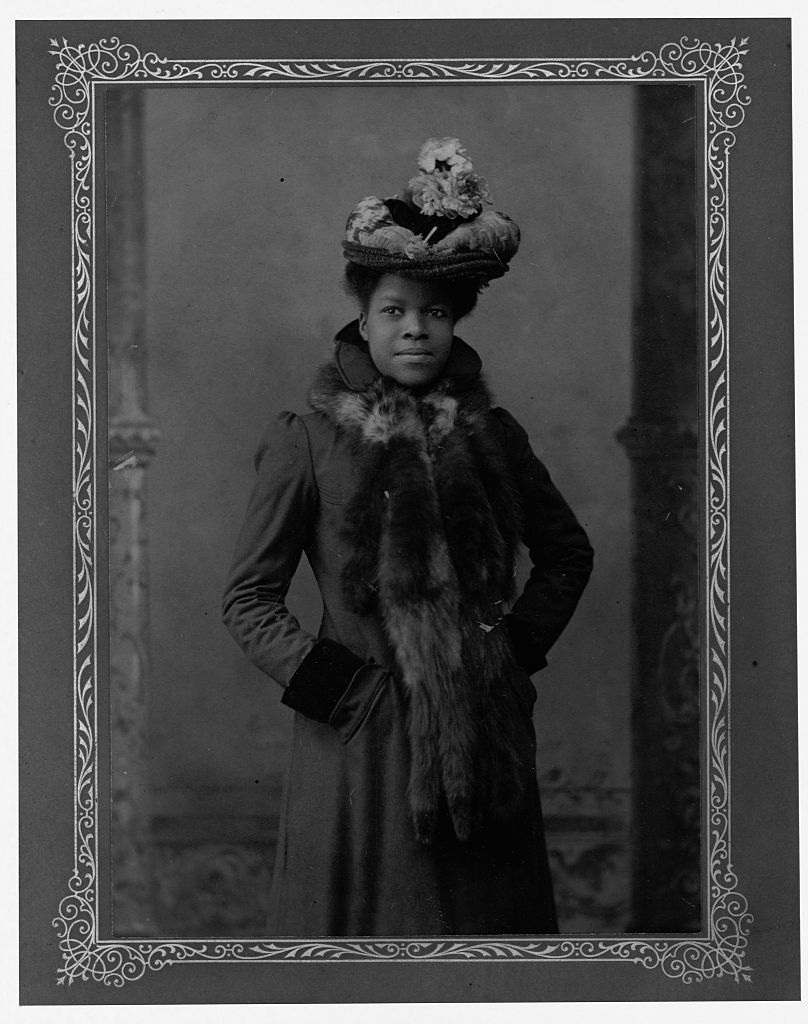

And while these particular voter-turnout efforts have recent roots, having become better known in the aftermath of Abrams’ historic run for governor, they’re also part of a long—and often overlooked—tradition of voting-rights activism led by Black women.

In the history of voting rights, the stories of Black women are often “held out at moments when they are convenient or they seem to serve another argument or purpose,” Martha S. Jones, the author of Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All, told TIME recently. “But too often we don’t get the full sense of their lives and how they are connected to their own histories and the histories of other Black women.”

Those histories go all the way back to the beginning of the modern American movement for women’s political rights. Sojourner Truth represented Black women at the first national women’s rights convention in 1850 in Worcester, Mass., and the following year, in her famous “Ain’t I a Woman” speech, she laid out the core argument that fueled voting rights activism for decades: that equal access to the ballot is a matter of human rights. After having campaigned for Civil War General Ulysses S. Grant for President in Michigan in 1872, she—alongside several other suffragists nationwide—tried to vote and got turned away, thus raising awareness of the issue.

“One of the things I always say—and I teach Black women’s history—[is that] most of the activists I’ve studied don’t just focus on one cause, because our lives intersect in so many places,” says Daina Ramey Berry, a historian at the University of Texas at Austin. “That’s why you’ll see Truth fighting for freedom and the abolitionist of slavery, but also fighting for women’s rights. You’ll see this across time. There’s not like this monolithic focus on one type of activism.”

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

But as the suffrage movement continued into the early 20th century, many white suffragists excluded Black women from their activism, in a calculation meant to appease white supporters they were trying to rally. As a result, despite their activism, Black women end up underrepresented in some of the most famous moments from the history of voting rights. For example, roughly two dozen members of the Delta Sigma Theta sorority at Howard University walked in the March 3, 1913, women’s suffrage parade in Washington, D.C.—a precursor to the Black sorority sisters who went viral on social media for their “stroll to the polls” in Atlanta this election cycle—but they are believed to have been the only African American women’s group to participate in that march. (Ida B. Wells marched in that parade as well, representing the suffrage club she founded, but not as part of a group.)

This dynamic means that finding the stories of Black voting rights activists often requires going beyond the mainstream versions of the white voting-rights story. Kellie Carter Jackson, a historian at Wellesley College, points out that, while Tennessee is hailed as the state that put the 19th Amendment over the threshold for ratification in 1920, thus extending the franchise to women, popular versions of that story often leave out the Black women who fought for that cause—like Juno Frankie Pierce and Mattie E. Coleman, who helped 2,500 Black women get the right to vote in Nashville’s 1919 municipal elections and become among the first Black women eligible to vote in the South.

Even after the ratification of the 19th Amendment, Jim Crow state laws meant that Black Americans were in many cases still unable to exercise the right to vote. So as white suffragist groups disbanded, the burden fell to Black women’s groups to keep marching to achieve full voting rights. And they did.

In the 1920s and 1930s, Mary Church Terrell and Nannie Helen Burroughs were key leaders of organizations for Black women voters, and educators like Septima Clark set up citizenship schools to prepare women for the obstacles they would face trying to vote. Other Black women created their own newspapers, magazines, and pamphlets, to publicize their fight for voting rights.

Black women carried on these voter-education efforts through the early 1960s, at churches and bus stops and beauty shops, on farms and at community meetings. But they rarely became household names, especially as the male leaders of the fight for voting rights were the spokespeople who talked to and got quoted in news outlets, and there was a lot of chauvinism, as the late Congressman John Lewis pointed out in his memoir.

One of the most powerful voices for Black women’s voting rights came out of this period, when, at a community meeting at a church in rural Mississippi in 1962, a sharecropper in her 40s named Fannie Lou Hamer found out she could register to vote. Though she lost her job for doing so, she gained a reputation as one of the most important voting rights activists of the 1960s. As a Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee field secretary, she crisscrossed the country speaking to fellow Black farm workers about the importance of voting. “When Hamer became aware of her constitutional rights, she was determined to use them,” historian Keisha N. Blain, who is working on a biography of Hamer, has written for TIME. “But even more, she wanted to ensure that others would also benefit from this knowledge.”

In her story, experts see many parallels to the women who organized the vote in Georgia this year.

“Like Fannie Lou Hamer, Stacey Abrams didn’t let people who turned her away or cheated the system, she didn’t let that stop her,” says Berry.

In 2013, the Supreme Court invalidated part of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, the law that had brought to fruition many of the goals of Hamer and her peers. That change helped shape the world in which voting rights activists like Abrams do their work. On Nov. 9, Abrams tweeted that her get-out-the-vote organization Fair Fight had raised $6 million in three days for those races. Georgia organizers’ efforts paid off in the Jan. 5, 2021, U.S. Senate run-off elections. Black turnout was key to helping Democrats Rev. Raphael Warnock and Jon Ossoff win their races, allowing their party to regain control of the U.S. Senate.

That dedication to moving forward is one these historians recognize in the women who paved the way for today’s activists—and, they point out, there’s another parallel too: that often under-recognized voter-encouragement work by Black women stands to impact people of all races and genders.

“It’s been left up to Black women not just to open up the door for themselves, but in opening up the door for themselves they open up the door for every other women of color, white women included,” says Jackson. “We deserve to count and to matter and to have our voices heard, and the only way you can do that politically is with a vote.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com