Grace Ndiritu has always thought of her work as both spiritual and political. The British-Kenyan artist uses video installations, paintings and performance practices with different communities, working with groups including refugees in Brussels and Indigenous activists in Argentina. Since 2012, she’s been working on a personal project called “Healing the Museum,” stemming from her feeling that museums were not connected with what was going on in the outside world, and were not welcoming to all communities. “I felt like the way to change or engage with museums is to use other methods like shamanism and meditation to open up the discussion about how we use objects and how we interact as people together in museum spaces,” she says.

As part of a two-year international project titled “Everything Passes Except the Past,” Ndiritu was invited by Germany’s Goethe Institute to hold a “Healing the Museum” performance and workshop last year in the Royal Museum for Central Africa in Brussels. The institution has a loaded history: it was initially built in 1898 to showcase the colonial spoils and violence led by King Leopold II in what was then the Congo Free State, even housing a “human zoo” in the museum’s gardens. After a long-awaited renovation promising to address and revamp the museum’s telling of its colonial history, it reopened in 2018 to mixed reactions. A year later, Ndiritu held a meditation workshop in one of the museum’s rooms showcasing objects, specifically mineral artifacts, that had been stolen from the Congo. For Congolese artist Freddy Mutombo, joining the workshop in this setting had a profound effect on him. “For me, this room symbolizes the current suffering of the Congolese people and the war for minerals. So it was all the more powerful.”

Debates over the restitution and repatriation of looted colonial-era objects from European museums back to their sites of origin have been happening for decades. But this year, amid the Black Lives Matter movement originating in the U.S., and broader protests against racial injustice across Europe, more people are connecting the scars of colonial violence to its modern-day legacies.

Read More: Why a Plan to Redefine the Meaning of ‘Museum’ Is Stirring Up Controversy

These considerations coincide with the culmination of “Everything Passes Except the Past,” which brought together artists like Ndiritu and Mutombo, as well as curators, art historians and educators from across Africa, Latin America and Europe to explore the colonial heritage of European museums. The Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo, an Italian arts gallery based in Turin, is hosting an exhibition featuring the work of Ndiritu and other artists in response to these themes.

The project comes at an interesting time for both Germany and Italy, which experienced waves of protests against racial injustice this year. As the pandemic and the eruption of the Black Lives Matter movement have prompted people to reflect on issues like restitution, institutions across Europe are grappling with how to respond to demands for the return of objects. These debates are particularly fraught in Germany and Italy. The German colonial empire occupied large parts of modern-day African countries in the late 19th and early 20th century, including Rwanda, Tanzania and Cameroon. It also committed the first genocide of the 20th century, against the Herero and Nama people of modern-day Namibia; earlier this year, the Namibian president turned down the German government’s offer for reparations saying that compensation and terminology used needed to be revised. Italy’s colonial empire included Eritrea, Ethiopia and Libya, and under Fascist leader Mussolini in the 1930s, expanded and consolidated its empire, merging these countries to become the Italian East Africa colony. Observers note today that the country’s colonial history is not taught in schools and is rarely acknowledged by politicians. The Black Lives Matter movement struggled to take off in Italy in the same way as other European countries this summer, although the brutal beating and killing of a young Black man near Rome sparked public outcry in September.

How the restitution debate has changed in recent years

In 2017, French President Emmanuel Macron gave a speech in Ouagadougou, capital of Burkina Faso, in which he promised that the return of African artifacts would be a “top priority for his government.” Art historian Didier Houénoudé says that speech set a different tone for the debate on restitution. “We went from a categorical and polite refusal to an expression of a possibility of discussion, from a ‘No! Impossible!’ to a ‘Yes, maybe but…,’” says Houénoudé, who is a specialist in Beninese cultural heritage and contemporary art, and also participated in the “Everything Passes Except the Past” project.

Macron later commissioned Senegalese economist Felwine Sarr and French art historian Bénédicte Savoy to investigate the question of repatriation in France. Their groundbreaking 2018 report called for French museums to permanently return an estimated 90,000 sub-Saharan African artifacts, if the country of origin asks for them. The report also suggested a procedure for their return. “[The origins of these artifacts] is no longer a secret. Now more people are realizing this is a war-related and colonialism-related issue, and there’s more knowledge, awareness and transparency,” Savoy says.

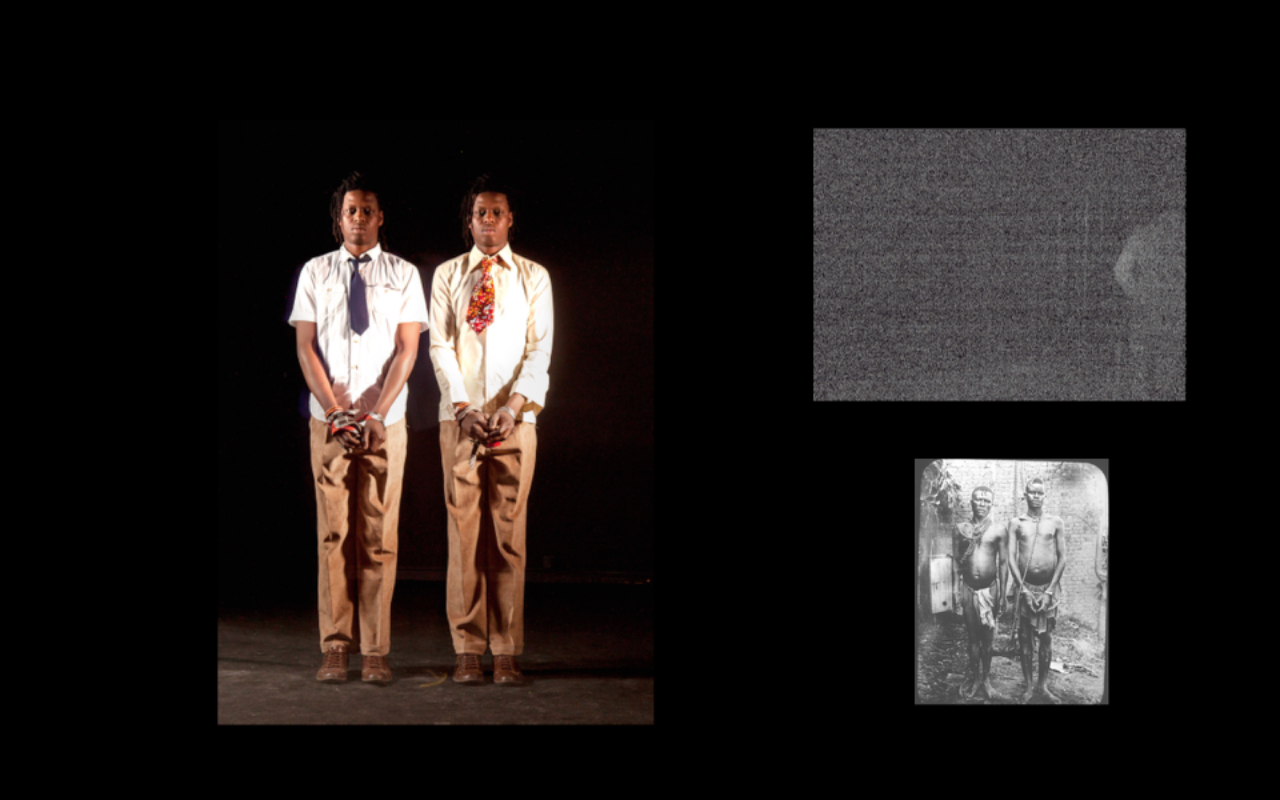

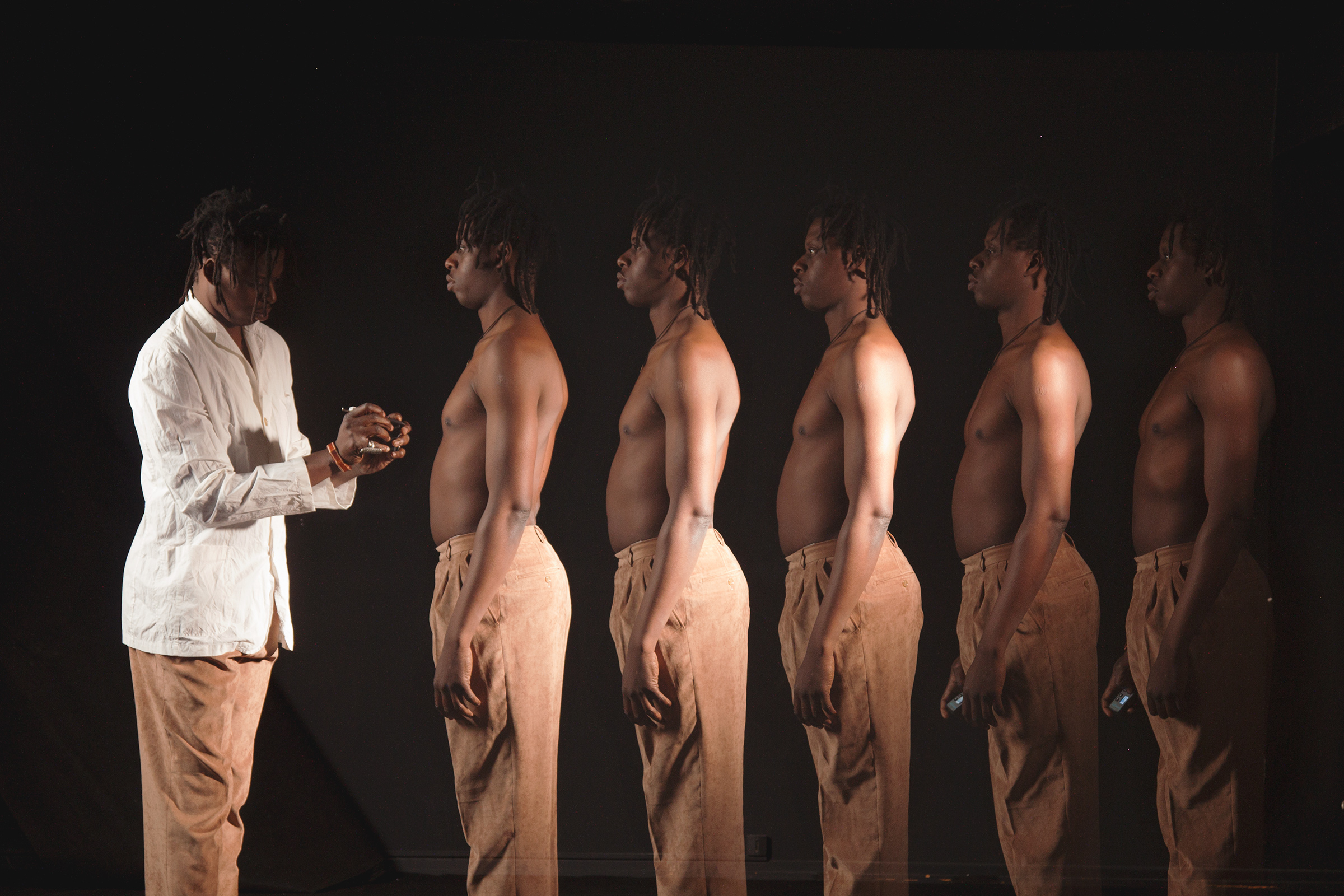

For artist Mutombo too, there has been an evolution in attitudes towards restitution since Macron’s announcement. Mutombo’s artistic practice is multidisciplinary, and reflects on the history of the Congo. His recent project, titled “Explorations,” uses archive images from the Congo during the colonial era. “History has a central place in my work,” he says. “I think of it from a double point of view: that of the colonized and that of the colonizer.” Mutombo says that in recent years, it has become much easier for him to access the archives at the Royal Museum for Central Africa near Brussels. He says that his requests for archival material used to be refused, but the museum now supports his work.

Action has been slow

While some museums have shown themselves to be more willing to engage in these discussions, others have “shown their anguish at seeing themselves stripped of the collections they hold,” says Houénoudé. Although a recent bill passed through the French Senate that would guarantee the permanent return of 26 objects looted from Benin during a violent 19th century siege, as well as a Senegalese sword and scabbard, no items have been returned permanently from French museums since Sarr and Savoy made their recommendations two years ago. The British Museum too has been critiqued for announcing plans to loan the Benin Bronzes back to Nigeria, rather than permanently return them. “In a way, colonization continues, and Europe does not want to give back the thousands of objects it has badly acquired,” Mutombo says. “Paternalistic and unbalanced relationships have not disappeared with the wave of a magic wand.”

He is not alone in critiquing the slowness of museums to act, rather than only talk or debate about the issue of restitution. For art historian Houénoudé, the cooperation and dialogue between European countries and African states has mostly been one-sided, and often condescending on the part of European states. “Europe gives (lessons) and Africa receives (these lessons),” he writes in an email to TIME.

How African artists, activists and curators are taking matters into their own hands

Historically, arguments against restitution and repatriation have included the claim that “African institutions may lack capacity and resources to preserve, research, and display [objects] adequately,” according to a recent report by the African Foundation for Development. Some say this reflects an ongoing paternalistic attitude towards African countries, where curators and experts have for some time been planning how to best store and display these objects in ways more relevant to their specific cultural context. Yaa Addae, a Ghanaian writer and researcher who took part in a workshop in Lisbon as part of “Everything Passes Except the Past,” is planning a series of community workshops looking at the futures of restitution, and what it might look like when a community, rather than a state or government, takes stewardship of returned ancestral art and objects. She’s been inspired by the work of indigenous and Black American curators and activists, as well as institutions who have approached restitution in innovative ways, like Yale Union, a contemporary arts centre in Portland, Oregon, which repatriated its only building to a Native American group earlier this year.

“Even in Ghana, we still use colonial forms of display,” says Addae, who has been thinking of ways objects can connect with communities. “I’m looking at case studies for how to reintegrate loot back into communities, and how to work against that paternalistic idea of, ‘oh we can’t return the art because nobody knows how to look after it,’” she says.

Addae, along with artist Ndiritu and other participants of the project, wrote an essay about her practices for inclusion in a catalogue to accompany the project, scheduled to publish in December. In her contribution, Addae writes about the different forms museums could take, and how objects in Ghanaian culture are not just works of art, but works of craftsmanship with purpose and function, like ancestral masks for example. “It doesn’t seem helpful to have something that was made to be used in life and the community behind a glass wall with a label, and not honoring its true intention,” she says. Addae previously worked with the ANO Institute of Arts and Knowledge in Accra, Ghana, as a researcher on their mobile museums project, which reimagined a museum as dynamic rather than fixed in one location, moving around different regions of Ghana and interacting with different communities to tell their own histories through their words.

Across the continent, researchers and experts are preparing to safely receive and conserve their cultural heritage. Benin City, the capital of Edo State in Nigeria, will host a new Benin Royal Museum, intended to house the famous Benin Bronzes and scheduled to open in 2021. In Senegal, the Museum of Black Civilizations opened in 2018, and currently holds the sword and scabbard included in the list of objects that France could move to permanently return.

Some fear that despite African efforts, European institutions remain unwilling to reckon with the past. Mutombo points to the case of Belgium’s legacy in the Congo. While he would like to see restitution of at least 70% of the Royal Museum for Central Africa’s collections to the Congo, he doesn’t think Belgium is prepared to recognize “the dark side of its history” in the country.

And some are refusing to wait for European museums to stop talking about restitution and reparation and are starting actions in a literal sense. In June, Congolese activist Mwazulu Diyanbanza, along with four other activists, livestreamed themselves attempting to remove a Chadian funeral staff from display at Paris’ Musée du Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac. Four activists were charged in October of aggravated theft and received fines.

The lack of African cultural heritage in Africa will only lead to greater discontent among younger people, says Houénoudé, who is also a lecturer and teacher at University Abomey-Calavi in Benin. He says many of his students support Diyabanza’s actions as a legitimate way to reclaim their heritage. “It is painful that others always want to teach us about how we preserve our heritage, about our history that these others have themselves painstakingly destroyed.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com