In every generation, citizens of a republic have to decide what to do if their country is on a course they consider unjust or immoral. Today this decision confronts those frustrated and outraged by police brutality and other aspects of a status quo that produces persistent racial and economic inequality. In the 1960s, opponents of the war in Vietnam asked themselves what forms of resistance to government policy were justified and appropriate.

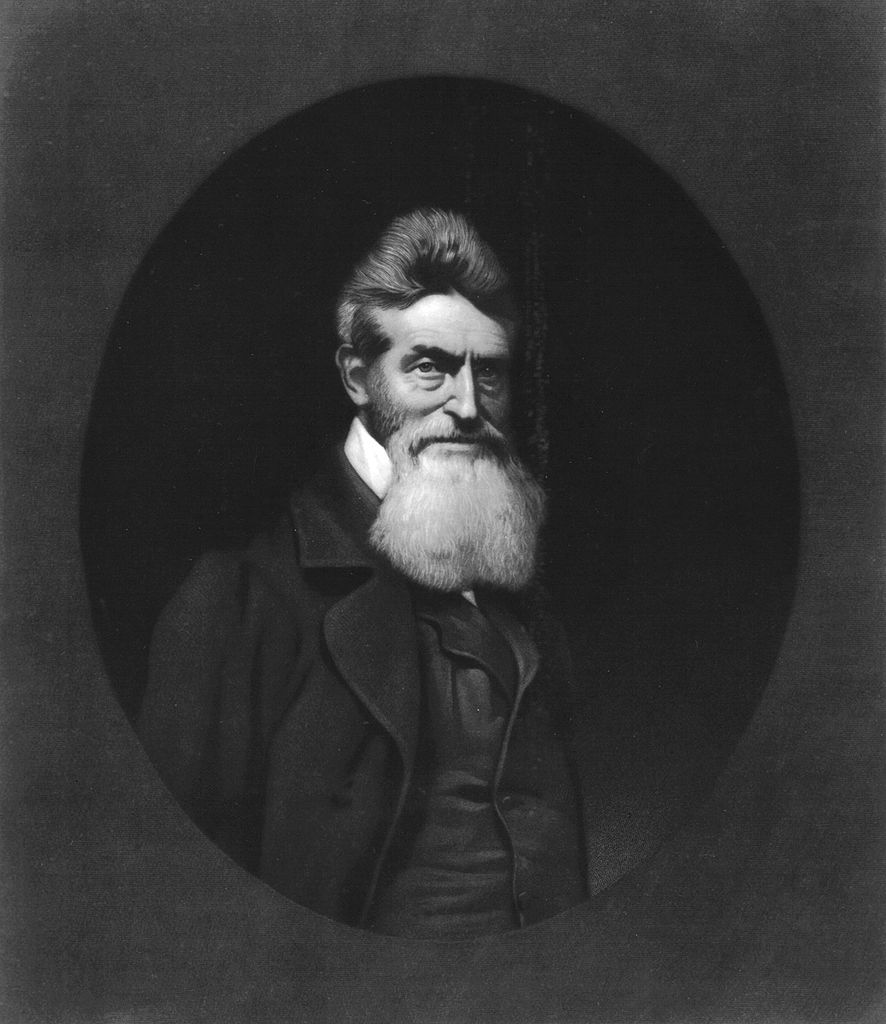

In the mid-19th century, John Brown pondered the means by which slavery should be challenged. Connecticut-born, Ohio-bred Brown had never liked slavery, but not until the death of Elijah Lovejoy—an abolitionist editor in the free state of Illinois, who was killed by a proslavery mob—did Brown make opposition to slavery his life’s work. He stood up in his church in Hudson, Ohio, and declared, “Here, before God, in the presence of these witnesses, from this time I consecrate my life to the destruction of slavery.”

At first, this consecration took the form of organizing and campaigning. Brown joined forces with abolitionists in New England and New York, including Frederick Douglass. He moved his family to North Elba, N.Y., where wealthy abolitionists had established a colony for free Black people. He urged free Black men and women to make common cause, by arms if necessary, with their brothers and sisters in chains. He organized something he called the League of Gileadites, named for Gilead, the mountainous region east of the Jordan River; his idea was to encourage slaves to escape to the Allegheny Mountains, and from there to Canada.

Then came the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, which opened Kansas Territory to settlement on the principle of “popular sovereignty.” The brainchild of Senator Stephen Douglas of Illinois, popular sovereignty encouraged emigration to Kansas by proslavery and antislavery settlers alike; when a sufficient population of residents had been reached, they would vote to make Kansas a slave state or a free state.

The new law turned Kansas into a battleground. Advocates of slavery poured across the border from slave-state Missouri, while opponents of slavery raced to the territory from farther away. John Brown joined the fight, along with several of his adult sons. Brown, like most opponents of slavery, had thought the Missouri Compromise of 1820 had secured the northern part of the Louisiana Purchase, including Kansas, for freedom; he was incensed at what he considered Douglas’ double-cross. He grew more incensed when proslavery guerrillas in Kansas descended on the antislavery settlement of Lawrence and ravaged the place.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

Brown concluded that violence justified violence. He gathered a small band of antislavery men who in the middle of the night dragged five proslavery settlers from their cabins and hacked them to death. The murders shocked Kansas and the country. Authorities in Kansas linked Brown to the killings and sought his arrest, but he changed his name and appearance and made his escape. He took refuge with other abolitionists, who declined to press him on whether he had actually done what he was being accused of. And he talked them into supporting a larger assault on the slave system, again deflecting questions that might compromise him or them.

In October 1859 the world learned the details of Brown’s scheme. He led his followers to Harpers Ferry, Va., where they seized and occupied a federal arsenal. Their goal was to distribute the arsenal’s weapons to enslaved men in the vicinity who would rise up against their masters and take their freedom by force. They believed that the example of Harpers Ferry would spread across the South, shaking and ultimately destroying slavery as an institution.

Things didn’t go as planned. Harpers Ferry was easier to get into than get out of, and Brown and his men were quickly surrounded. More crucially, slaves in the area refused to join what they deemed—accurately, as it turned out—a suicide mission. Brown and his surviving followers were captured and imprisoned. On his way to the gallows, following his conviction for treason against Virginia and murder of individuals killed in the raid, Brown passed an ominous note to a guard declaring, “The crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood.”

He was more right than he could have imagined. The raid on Harpers Ferry—and the adulation Brown received from Northern abolitionists—caused many slaveholders to think their institution and their very lives were in danger as long as the South remained part of the Union. Southerners were thus primed to react decisively when Abraham Lincoln, the nominee of the antislavery Republican party, was elected president in 1860. Seven Southern states quickly left the Union and formed a new country, the Confederate States of America. Four more states joined them after fighting began at Fort Sumter.

Lincoln initially tried to separate the issue of slavery from that of secession. The Southern states could keep slavery as long as they wanted, he said, but they could not leave the Union. Yet when this argument failed, Lincoln concluded that preserving the Union required freeing the slaves, and in the Emancipation Proclamation he embraced freedom for the enslaved as a fundamental Union war aim.

By the end of the war, Brown’s bloody prediction was being treated by many in the North as akin to divine revelation. Even Lincoln, who had condemned the Kansas murders and the Harpers Ferry raid, echoed Brown when, in his second inaugural address, he allowed that it might be God’s will that “every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword.”

Yet one has to take great care in drawing lessons from Brown and Lincoln. Brown demonstrated that a person can be on the right side of history and still go terribly wrong. His Kansas murders were inexcusable, his raid was a failure and the war he helped trigger killed perhaps 700,000 Americans—the population equivalent of more than 7 million today. As the death toll mounted, some opponents of slavery judged the war deaths a necessary atonement for slavery’s evil, but no one would have accepted such ghastly arithmetic ahead of time. Surely even Brown would have quailed at the carnage. And so should we, no matter how much we applaud the war’s role in emancipation.

A more apt lesson follows from something else Lincoln said. Before the war began, he appealed to “the better angels” of Americans’ nature to halt the slide toward disaster. The angels weren’t listening, and the war came. We are not on the brink of war now, and we certainly hope we don’t go there. But as tension and violence mount, the sobering memory of the Civil War should encourage us to heed the voice of our own angels when it tells us not to let our good intentions lead us astray.

H.W. Brands is the author of The Zealot and the Emancipator: John Brown, Abraham Lincoln and the Struggle for American Freedom, available now from Doubleday Books.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com