Juan Olivarez was 24 when he first went to the United States in 1966. He entered as a tourist, but he really went to work. After returning to his small town in the central-western Mexican state of Jalisco the following year, he headed north again and found jobs picking beets, tomatoes and cherries in California. Olivarez and some friends later went to Oregon, where they repaired train tracks until, one night after dinner, an immigration officer knocked on their door and asked to see their papers. “We told him, almost in unison, ‘We don’t have any,’” Olivarez recounted. He spent the next week being shuffled between four different jails and detention centers in California and Texas before authorities finally deported him.

Olivarez’s expulsion is one of nearly 50 million deportations U.S. authorities have carried out during the last half century. Between the late 1970s and the late 2000s, annual expulsions exceeded one million, on average, and rarely dipped below 900,000 in any given fiscal year. Though the years before had seen the episodic enforcement drives, such as those of the Great Depression and the infamous “Operation Wetback” campaign of the 1950s, the magnitude and regularity of deportations after 1975 marked a break from the past and the dawn of a new era: the age of mass expulsion.

Like Olivarez, some 90% of the people pushed out of the country during the 20th century were Mexicans deported via a coercive, fast-track administrative process euphemistically referred to as “voluntary departure.” Similar to prosecutors in the criminal justice system relying on plea bargains, immigration authorities depended on voluntary departure, making it seem like the best of all the bad options facing people who had been apprehended. These deportations without due process also functioned as a cost-saving measure, since they minimized detention-related expenses and reduced the number of immigration hearings.

In the 1970s, immigration authorities’ near-exclusive reliance on voluntary departure, the United States’ dependence on cheap migrant labor and the border’s relative porousness combined to create a revolving door effect and a sense of perpetual crisis.

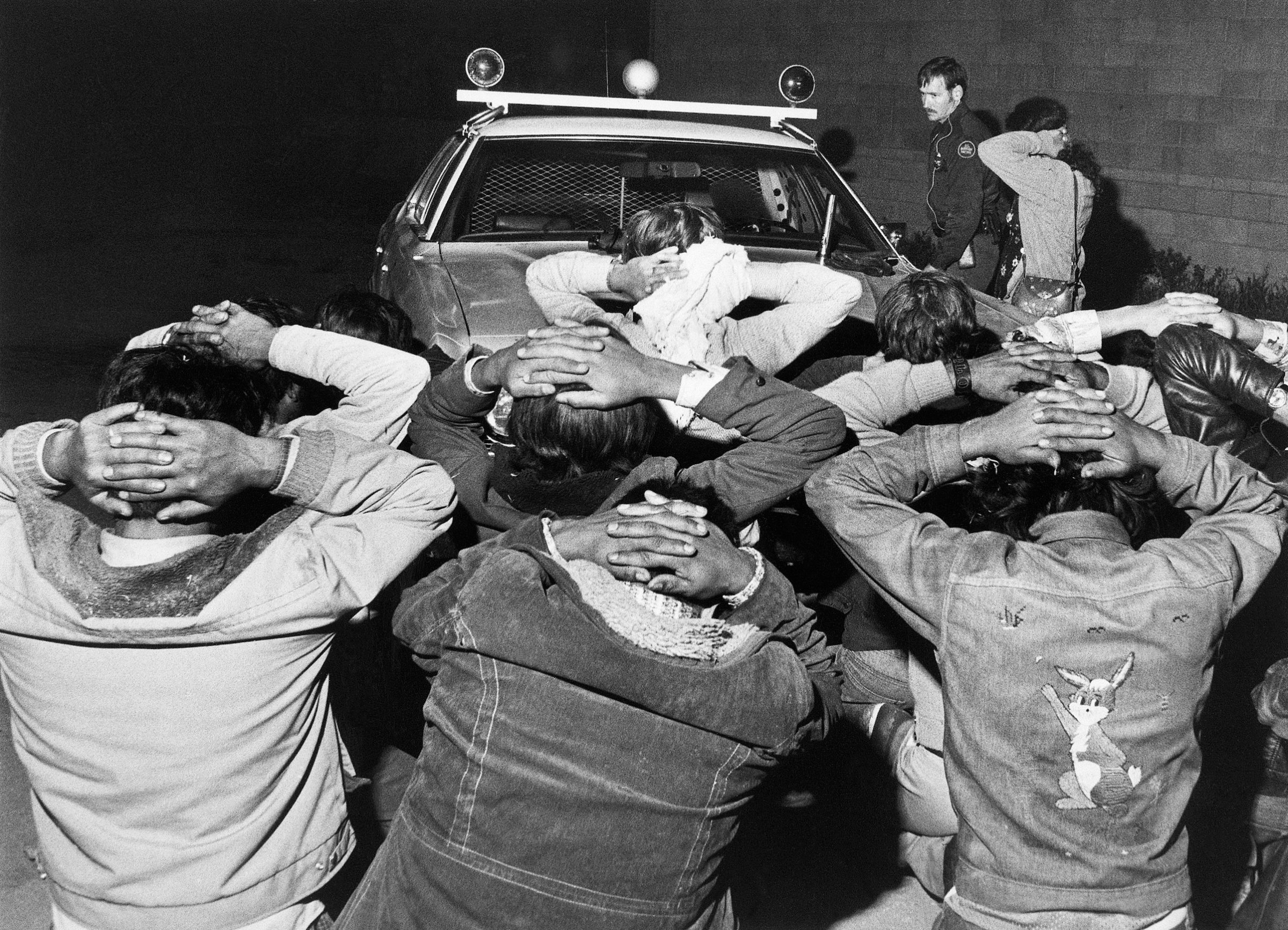

While most apprehensions occurred at or near the border, agents (with assistance from local police forces) also targeted millions of people living in the nation’s interior, many of them long-term U.S. residents. This caused widespread anxiety in immigrant communities and the establishment of de facto internal borders that circumscribed the physical spaces people inhabited, and sometimes confined them to their homes.

Deportation, or the possibility of being deported, became a part of many people’s everyday lives during this period. A man I’ll call Jorge was well aware of the fact that when he left for work each morning there was always the possibility that he wouldn’t return home. Fearing apprehension, he always carried $20 with him, hidden somewhere on his body, to ensure that he would have a little bit of money if immigration agents deported him to Tijuana. The precaution was not unreasonable: on many occasions agents showed up at the ranch where he worked, forcing him and his friends to flee.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

Ongoing demand for migrant labor, wage differentials and the desire to reunite with family often led migrants to return to the United States after being deported to Mexico. As a result, authorities expelled many people on multiple occasions. They removed Alfonso, a 27-year-old man who first entered the United States in 1968, seven times during his first five years in the country. In 1977, officers in El Paso apprehended Laura Mendarez-Pérez, who supposedly had 48 prior deportations. Officials in San Diego claimed to have detained another man 25 times. As the immigration commissioner put it during a television interview in the late 1970s, “We catch them in the morning, we deport them in the afternoon. We apprehend them. We deport them. We deported one guy five times in one day out of El Paso. It’s just an unbelievable revolving door.” The number of people deported who had at least one previous expulsion increased from fewer than 14,000 in 1965 (13% of all deportees) to more than 372,000 in 1985 (35% of all deportees).

The nature of border enforcement angered agents on the ground, but it actually served the interests of the immigration bureaucracy. As sociologist Gilberto Cárdenas has noted, authorities turned to statistics to create “a sense of alarm, urgency and a call for action.” They used the ever-rising number of apprehensions and deportations inherent to the revolving door system to simultaneously celebrate their “accomplishments” and to draw attention to the dire need for additional funding, all while helping to fulfill the United States’ labor needs, since migrant workers continued to cross the border.

“The pressure from the top people in the administration . . . is extreme,” a former statistician for the immigration service explained in the mid-1970s. “We are told periodically that ‘the heats [sic] on,’ and we know that we had better get to work and make it look like we’re after the ‘devils’ who are taking away the jobs from the little-man.” To do so, he and his colleagues turned to the media, which he described as “one of our best tools in emphasizing the threat that the illegals pose to the stability of the economy.” The media obliged with xenophobic coverage that scapegoated Mexicans for the country’s economic woes.

The constant cycle of unauthorized migration–apprehension–deportation–repeat unauthorized migration led officials to increasingly single out Mexicans. In fiscal year 1965, the 55,000 Mexicans apprehended represented 50% of all apprehensions; two decades later, the 1.2 million Mexicans apprehended made up 94% of total apprehensions. The Border Patrol’s obsession with stopping Mexican migrants eventually led them to split their apprehension statistics into two categories: Mexicans and “Other Than Mexicans,” or “OTMs” in agency lingo. The fact that officers were tasked with barring both people in search of work as well as narcotics and drug smugglers sometimes led to the conflation of the two, which further demonized Mexicans within the immigration agency, in the media and in the public’s imagination.

Ultimately, officials’ disproportionate targeting of a single group created and reified racist stereotypes of ethnic Mexicans—irrespective of citizenship or legal status—as prototypical “illegal aliens.”

Excerpted from The Deportation Machine: America’s Long History of Expelling Immigrants (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2020)

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com