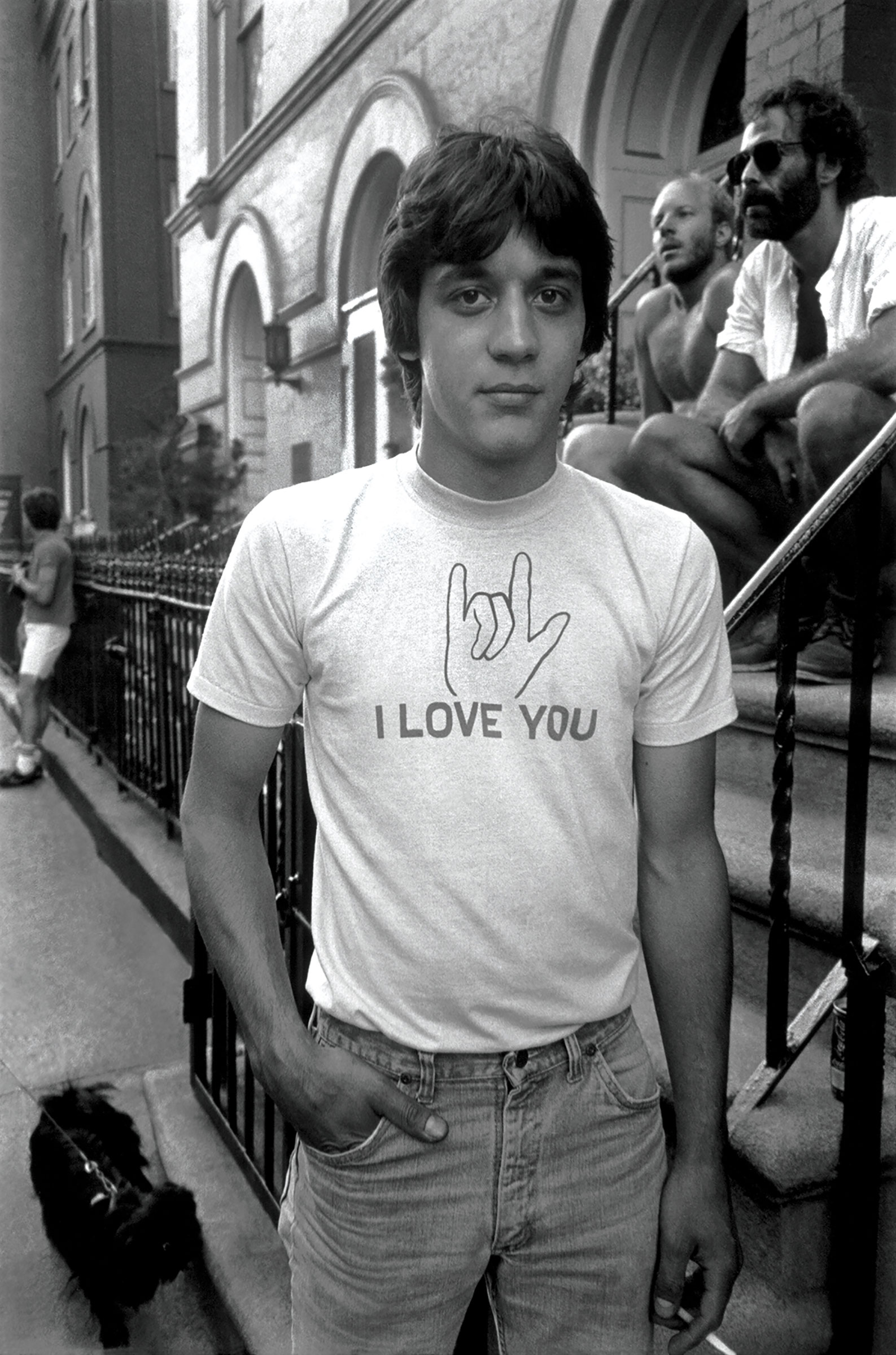

Recalling the first years of Pride celebrations in the early 1970s, photographer Stanley Stellar remembers how all the energy was concentrated in a small area of Christopher Street in New York City’s West Village. At the time, it was the rare neighborhood where gay people could go and meet in public, and Pride parades operated at a neighborhood-level size too — a far cry from the estimated five million people who attended last July’s World Pride event in New York City, the largest LGBTQ celebration in history.

“It started as a small social thing,” Stellar, now 75, recalls. “There were marchers too — very brave souls with signs, like Marsha P. Johnson, who inspired all of us. When people would taunt us, cars would drive by and spit at us, yell at us constantly, Marsha would be there, looking outrageous and glorious in her own aesthetic, and she would say ‘pay them no mind.’ That’s what the ‘P’ is for, is ‘pay them no mind, don’t let them stop us.’”

That unstoppable spirit is now marking its 50th anniversary: the first Pride parades took place in the U.S. in 1970, a year after the uprising at the Stonewall Inn that many consider to be the catalyst for the modern LGBTQ liberation movement. In a year when large gatherings are prevented by the coronavirus and many Pride events have been cancelled or postponed, over 500 Pride and LGBTQIA+ community organizations from 91 countries will participate in Global Pride on June 27. But, over the decades, Pride parades have evolved in a way that goes beyond the number of participants — and, having photographed five decades worth of them, Stellar has seen that evolution firsthand. “That was the epicenter of the gay world,” he says of the early years of Pride.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

The Stonewall Uprising took place over a series of nights at the end of June 1969. Although the LGBTQ community had pushed back against police discrimination in several other smaller occasions in the late 1960s in cities like San Francisco and L.A., Stonewall cut through in an unprecedented way.

“People were ready for an event like Stonewall, and they had the communication and the planning in place to start talking right away,” says Katherine McFarland Bruce, author of Pride Parades: How a Parade Changed the World. Activist groups in L.A. and Chicago, which also held Pride Parades in 1970, immediately made connections with counterparts in New York to plan actions around the anniversary. Where in L.A., the spirit was more about having fun and celebrating, Bruce says, New York was planned more as an action to connect activists. “We have to come out into the open and stop being ashamed, or else people will go on treating us as freaks,” one attendee at the parade in New York City told the New York Times in 1970. “ This march is an affirmation and declaration of our new pride.”

By 1980, Pride parades had taken place around the world in cities like Montreal, London, Mexico City and Sydney. But as that decade got underway, the tone of the events shifted, as the tragedies of the AIDS crisis became central to actions and demonstrations. By this time, Stellar had a large circle of queer friends and started making more photos of the community to document their every day lives. “I really felt like I owed it to us, as in the queer ‘us,’ to start just photographing who I knew and who I thought was worthy of being remembered,” says Stellar, who has an upcoming digital exhibition hosted by Kapp Kapp Gallery, with 10% of proceeds going to support the Marsha P. Johnson Institute.

To Bruce, Pride shows how the LGBTQ community has been able to consistently demand action and visibility around the issues of the day.

Where in the 1980s, groups organized around the AIDS crisis, the 1990s saw greater media visibility for LGBTQ people in public life, leading to more businesses starting to come on board for Pride participation. While the Stonewall anniversary had long provided the timing for annual Pride events, President Bill Clinton issued a proclamation in 1999 that every June would be Gay and Lesbian Pride Month in the U.S. (President Barack Obama broadened the definition in 2008, when he issued a proclamation that the month of June be commemorated as Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Pride Month.)

The early 2000s then saw greater campaigning for same-sex marriage. During the summer of 2010, Bruce did contemporary research for her book, attending six different Pride parades across the U.S., including one in San Diego, home to the nation’s largest concentration of military personnel, where campaigning was concentrated on repealing the “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy. “I think Pride is a vehicle for LGBT groups to make the issues of the day heard both in their own community and in the wider civic community to which they belong,” Bruce reflects — adding that in recent years, campaigns for racial justice and transgender rights have become more prominent.

Yet as these intersectional injustices have risen to the forefront of public consciousness, several aspects of major, long-running Pride parades have come under greater scrutiny — returning Pride, in some ways, to its protest-driven origins.

Some LBGTQ activists and community organizers have criticized the corporatization of Pride, as parades look to businesses for sponsorship to help with the financial demands of rapidly growing crowds. Others question whether any deep-rooted action is behind the rainbow flags. “What happens on July 1 when our seniors can’t get housing, and kids are being thrown out of their homes, and both trans women and cis women are being murdered in the street? Have that rainbow mean something 365 days out of the year,” Ellen Broidy, a member of the Gay Liberation Front and co-founder of the first annual Gay Pride March in 1970, told TIME last year.

Activists in New York and San Francisco have started their own separate parades to protest police and corporate involvement at the more established parades, given both historic and contemporary levels of disproportionate policing of Black and queer communities. And, responding to the lack of diversity in the biggest pride events, organizers have started events to create a safe space for the more marginalized among the LGBTQ community. In the U.K., support has swelled for U.K. Black Pride, which started in 2005 as a small gathering organized by Black lesbians to come together and share experiences. The event is now Europe’s largest celebration for LGBTQ people of African, Asian, Caribbean, Middle Eastern and Latin American descent, and is not affiliated with Pride in London, which has been criticized in the past for its lack of diversity.

For others, living in environments where being gay risks state-sanctioned violence and even death, Pride events perform a function similar to that seen in places like New York in the 1970s, as a vital lifeline. Recent years have seen communities in eSwatini, Trinidad and Tobago, and Nepal organize to hold their first Pride parades. Activist Kasha Jacqueline Nabageser organized the first Pride celebration in Uganda in 2012, after realizing she had been to several Prides around the world but never in her own country, where long-running laws left over from the colonial era criminalize same-sex activity. “For me, it was a time to bring the community together, and for them to know they are not alone, wherever they are hiding,” says Nabageser, adding that people who might not have seen themselves as LGBTQ activists came to the event, and later joined in with advocating for gay rights in the country. At least 180 people showed up to the first event in the city of Entebbe, and while the Ugandan government has attempted to shut subsequent Pride celebrations down, Nabageser sees the retaliation as a sign of the community’s power in its visibility.

“The more [the government] stops us, the more they make the community more angry, and more eager for Pride. For us, that has been a win,” she says, adding that the community is planning ways to celebrate safely in small groups amid the coronavirus pandemic. “One way or another, we will have Pride, and we have to continue the fight.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com