In the past several weeks, as calls to defund the police have gone mainstream, pop culture critics and fans have been reconsidering how Hollywood heroizes cops. Legal procedurals and shoot-em-up action movies have long presented a skewed perception of the justice system in America, in which the police are almost always positioned as the good guys. These “good cop” narratives are rarely balanced out with stories of systemic racism in the criminal justice system. The “bad guys” they pursue are often people of color, their characters undeveloped beyond their criminality.

In this period of reckoning, the long-running show Cops and the widely-watched Live PD have been canceled. Actors and writers who contributed to police procedurals are criticizing their own work and donating money to the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. Parents are protesting benevolent portrayals of canine cops in the children’s television show Paw Patrol. And Ava DuVernay’s film collective ARRAY is launching the Law Enforcement Accountability Project (LEAP) to highlight stories of police brutality and counteract a biased narrative.

But as we engage in this long overdue conversation about law enforcement, it’s high time we also talk about the most popular characters in film, the ones who decide the parameters of justice and often enact them with violence: superheroes.

Cops with capes

Superheroes have dominated popular culture for the last decade—they are fixtures of the highest-grossing movies and icons to more than just our children. They are beacons of inspiration: protesters dressed as Spider-Man and Batman have turned up at recent Black Lives Matter demonstrations. And yet what are superheroes except cops with capes who enact justice with their powers?

With a few notable exceptions (more on those later), most superhero stories star straight, white men who either function as an extension of a broken U.S. justice system or as vigilantes without any checks on their powers. Usually, they have some sort of tentative relationship with the government: The Avengers work for the secretive agency S.H.I.E.L.D.; Batman takes orders from Gotham police commissioner Gordon; even the villainous members of the Suicide Squad execute government orders in exchange for commuted prison sentences. And even when superheroes function outside the justice system, they’re sometimes idolized by police because they are able to skirt the law to “get the job done.”

In fact, real-life police officers sometimes adopt the symbolism of these rogue anti-heroes. The Punisher, a brutal vigilante introduced in a 1974 Spider-Man comic who also starred in a 2017 Netflix series, has become an emblem for some cops and soldiers—to the point where Marvel felt the need to address this idolatry in the pages of its comics. In a 2019 story, a group of police fanboys run up to the Punisher and say, “We believe in you.” One shows off a Punisher skull sticker on his car. The Punisher rips the sticker off and says, “We’re not the same. You took an oath to uphold the law. You help people. I gave that up a long time ago. You don’t do what I do. Nobody does.” Another cop replies, “Like it or not, you started something. You showed us how it’s done.”

The Punisher is representative of a larger problem in superhero narratives. When Batman ignores orders and goes rogue, there’s no oversight committee to assess whether Bruce Wayne’s biases influence who he brings to justice and how. Heroes like Iron Man occasionally feel guilt about the casualties they inflict, but ultimately empower themselves again and again to draw those moral lines.

In the real world, meanwhile, tolerance for law enforcement acting with impunity is eroding. Those calling for the dismantling of modern policing point, in part, to the lack of consequences faced by officers who have killed Black people like George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and Elijah McClain and many others without being fired or prosecuted—or at least with significant delays and public pressure before action was taken. As these urgent conversations dominate the news, it’s increasingly unclear how either the “arm of the law” or the vigilante narrative can survive without serious reconsideration.

Most of the blockbuster Marvel and DC comics movies skirt the issue of who should define justice for whom. Captain America: Civil War and Batman v. Superman: Dawn of Justice briefly float the idea of superhero oversight but both devolve into quip-filled CGI fistfights. (In fairness, the Civil War storyline in the Marvel comics more thoughtfully plumbs the depths of that socio-political debate.)

What’s more, given that the creators and stars of these movies have historically been white men, it’s hardly surprising that so few reckon with issues of systemic racism—let alone sexism, homophobia, transphobia and other forms of bigotry embedded in the justice system or the inherent biases these superheroes might carry with them as they patrol the streets, or the universe.

A new kind of hero

There is some history of reckoning with policing in Black superhero films. Blade, the 1998 Wesley Snipes superhero movie, launched the superhero movie boom we’re still in today, giving Marvel its first box office smash. The movie, written and directed by white men, references tensions between Black communities and the police. In one scene, two cops walk in on Blade fighting what is clearly a monstrous vampire and begin shooting at Blade instead. Blade turns around and asks, “Are you out of your damn mind?” It’s played as a throwaway moment, but one that rings true decades on. (Marvel announced last year that two-time Oscar winner Mahershala Ali will star in Blade reboot.)

More recently, racial injustice has become the centerpiece for some superhero films. The clearest example of that shift is Black Panther, Ryan Coogler’s 2018 superhero movie that takes as its main subject the oppression of BIPOC people worldwide. In that movie, Black Panther, a.k.a. T’Challa (Chadwick Boseman), rules over Wakanda, a secluded, scientifically-advanced African country unfettered by colonialism. He faces off against a would-be usurper named Killmonger (Michael B. Jordan), who argues that Wakanda must abandon its policy of isolationism and help combat systemic oppression across the world.

T’Challa eventually discovers that his own father and Killmonger’s father had a similar debate in the 1990s. When Killmonger’s father was deployed to America as a spy, he became radicalized by the racism he saw there. He smuggled weapons from Wakanda to help Black people suffering in America. When T’Challa’s father confronts Killmonger’s father, the latter argues, “Their leaders have been assassinated. Communities flooded with drugs and weapons. They are overly policed and incarcerated. All over the world, our people suffer because they do not have the tools to fight back.” Killmonger’s father eventually loses his life for his political stance.

T’Challa’s arc is to realize his nemesis is right: While Killmonger and his father broke laws and enacted violence for their cause, their conviction that people of color have historically lacked the tools to fight systemic oppression was correct. T’Challa eventually comes to represent a compromise between these two viewpoints: He uses his relative privilege to empower people who have been held back by colonialism and racism but finds non-violent methods to do so.

At the end of the movie, T’Challa opens a community center in Killmonger’s hometown, Oakland. He asks his girlfriend to run a social-outreach program for Black communities and his tech-savvy sister to head up an education program—the same sorts of community investment that activists calling to redistribute police budgets into social support systems are now calling for. A Black Panther sequel is in the works from Coogler, and audiences can expect further exploration of this tension between policing and community support.

When superheroes and cops collide

It’s not just that superheroes act like members of law enforcement; sometimes they interact with them directly. Spider-Man has long had a complicated relationship with the NYPD. Last year’s Spider-Man video game received some pushback over what many critics called “copaganda.” In that game, Peter Parker is a fan of the police, even fantasizing about being “Spider cop.” He spends much of the game fixing surveillance towers for the NYPD.

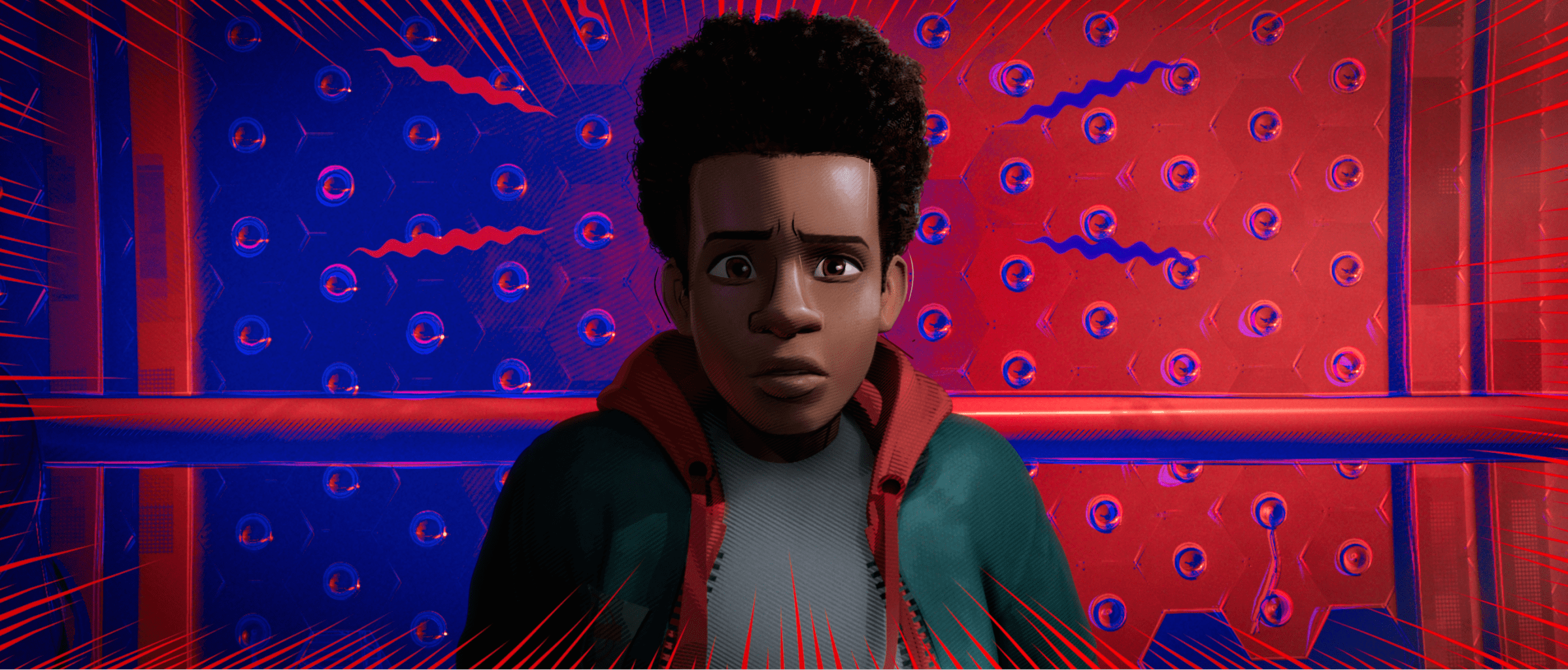

But the introduction of Miles Morales, who made his debut in the comics in 2011, could offer opportunities to explore the contentious relationship between New Yorkers and police. Miles, who is half-Black, half-Puerto Rican, is the son of a cop. In 2018’s animated Spider-Man: Into the Spiderverse, Miles’ father doesn’t know his son’s secret identity. Miles spends much of the movie trying to reconcile his father’s love for him with his dislike for Spider-Man as a vigilante.

A Spiderverse sequel is in the works, and many fans hope it will focus more on Miles (and less on Peter) and deal with race more directly. Before that, a Miles Morales video game will arrive, hopefully with a more nuanced take on the NYPD than the game that preceded it. With a Spider-Man who’s a young man of color in a city with a painful, recent history of stop-and-frisk policies disproportionately inflicting trauma on young Black and brown men, it will be a striking oversight if it doesn’t.

But the superhero property that most directly engages with corruption in policing is Watchmen. In Alan Moore’s 1986 graphic novel, vigilantes who believe they have the right to fight and live by their own moral codes often prove themselves despicable bigots or megalomaniacs. One particular image of so-called heroes confronting a riot looks an awful lot like the recent videos we’ve seen of police officers shooting rubber bullets and tear gas at protesters.

Still, the comic was a product of its time and its storylines that have not all aged well. Damon Lindelof’s 2019 HBO series adapted from the comic “remixes” the original story and serves as a spiritual sequel. (In recognition of its relevance to the current moment, HBO made all episodes briefly available to watch for free over the Juneteenth holiday weekend.) Unlike Moore’s story, which ultimately becomes a tale of white men fighting over power, Lindelof’s show begins with the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre. As Victor Luckerson writes in the New Yorker, that event was “the country’s most significant incident of racial terrorism, during which the city’s ‘Black Wall Street’ was strafed by planes and burned to the ground by white supremacists, abetted by the National Guard. It’s a true story that will be left out of schoolbooks, mislabelled a ‘race riot,’ and deliberately forgotten.” This misremembering of history becomes a theme of the show.

After that preface, the show fast-forwards to modern-day Tulsa and centers primarily on Angela (Regina King), a cop pursuing a white nationalist terrorist group akin to the KKK. In order to fight them, cops have begun to cover their faces and adopt superhero alter egos. The portrayal of the police is complicated: Angela, a Black woman, is a cop and the hero of the show. She also does some objectionable things, like kicking the crap out of a suspect in an interrogation room and lying to the FBI.

But as the mysteries unravel, it becomes clear that Watchmen’s real intent is to revisit one of the most lauded stories in the comic book world and re-examine it from the perspective of historically excluded Black characters. In doing so, the show reveals the connective tissue that links harm committed against Black people from the Tulsa Massacre to the racism that Angela deals with in the present day. Black heroes rise up to meet the darkest force, one that’s ignored by most superhero stories: racism.

The way forward

If Hollywood is to do better in telling these stories, more creators of color need to be given the reins to tell them. It’s worth noting that while Lindelof employed a diverse writers’ room, it likely took his name and cache as the creator of Lost and The Leftovers to get such an ambitious story greenlit. Similarly, while the director of Spiderverse, Peter Ramsay, became the first Black man to win an Oscar for animation, Sony initially approached the two white men (who ended up producing the film), Lego Movie directors Phil Lord and Christopher Miller, with the opportunity to make an animated Spider-Man.

Writers must also shake the notion that they are bound by the strictures of outdated intellectual property. These days, few big-budget projects move forward unless they are based on existing IP. But the success of Watchmen suggests that creators can snatch up those familiar characters and still weave a new story, with new politics and a new perspective, using only fragments of what came before. Just as the Watchmen series is a radical departure from a dusty Reagan-era graphic novel, both Black Panther and Into the Spiderverse borrowed the names and backstories of their main characters from the comics but took those characters in new and ambitious directions.

Only when this creative freedom is encouraged and Hollywood offers more opportunities to BIPOC creators—and white creators use their capital to support creators who are too often overlooked—will we get more superhero tales that adequately grapple with the complexity of justice in America.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Write to Eliana Dockterman at eliana.dockterman@time.com