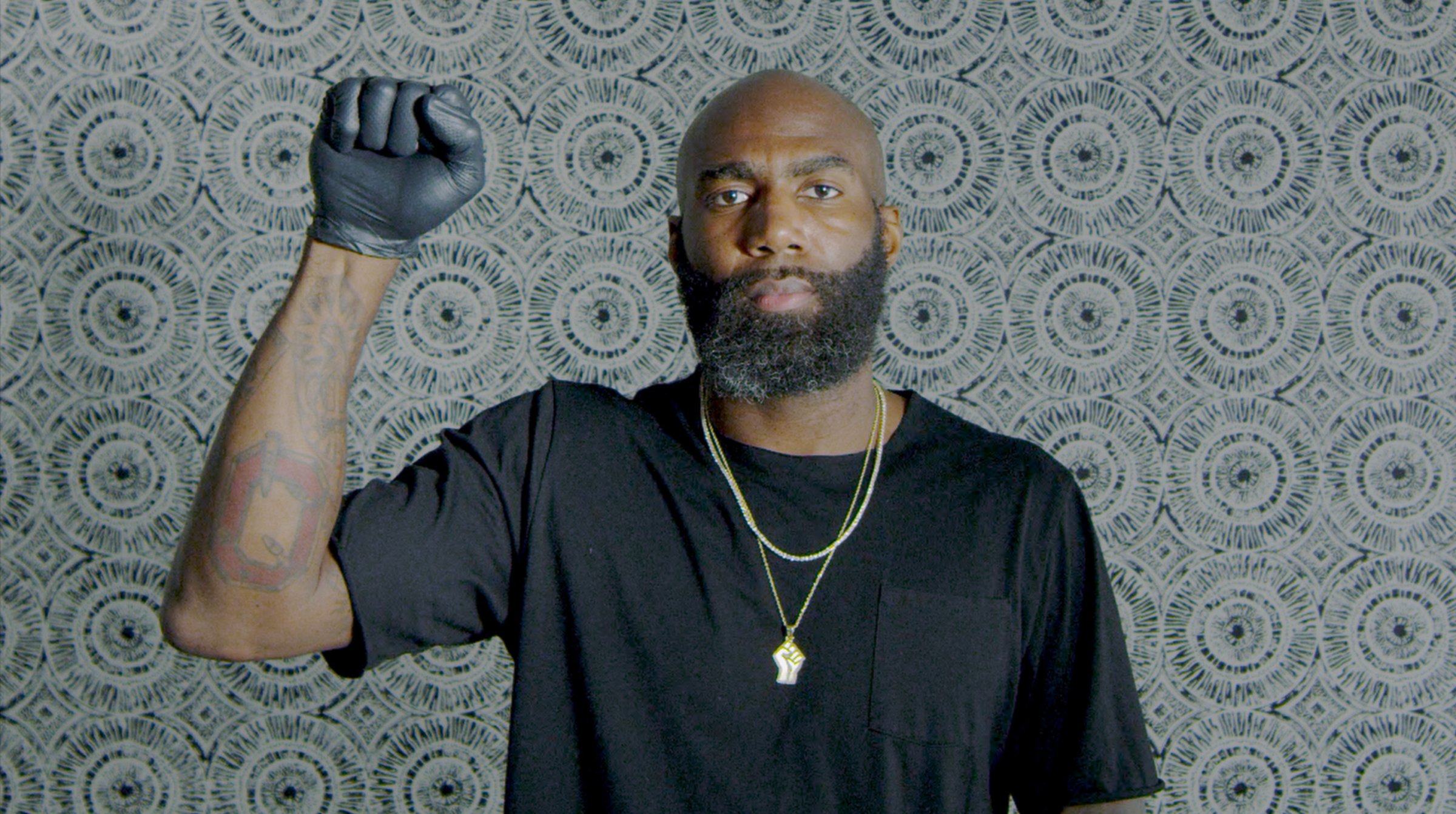

Amid a nationwide reckoning over police brutality and systemic racism in the wake of George Floyd’s killing, ESPN sought out, for its ESPYs award show, a voice in sports to capture this singular moment in our culture. New Orleans Saints safety Malcolm Jenkins, who’s spent the last few years lobbying national and state lawmakers for criminal justice reform, and whose tearful reaction to teammate Drew Brees’ comments equating kneeling during the national anthem to “disrespecting the flag” and “our country” captured the raw feelings of millions of Americans, immediately came to mind.

“We asked ourselves, whose voice might resonate most in a show set to air at such a crucial moment in our national discourse on racial equality and police brutality,” says Rob King, Senior Vice President and editor at large, ESPN Content.

Jenkins, who runs his own production company, Listen Up Media, jumped at the opportunity to serve as the creative force behind a powerful piece. After the 2016 deaths of two unarmed Black men at the hands of police, Alton Sterling and Philando Castile, Jenkins started wondering what more he could do to stop such incidents. Then a 2016 ESPYs segment, which featured LeBron James, Carmelo Anthony, Chris Paul and Dwyane Wade speaking out against police violence, inspired him to act.

“Just to kind of see that unexpectedly, it let me know that the things I was thinking about, they weren’t far-fetched,” Jenkins tells TIME in an exclusive interview about his ESPYs piece. “There were other guys who shared those sentiments. The social media, the hashtags and the T-shirts and all that stuff, is cool, but not enough. Their speeches in particular just sparked me enough to say, ‘I don’t know exactly what I’m going to do, but I’m going to go figure it out. It was that galvanizing moment for me.'” About a week later, Jenkins—then with the Philadelphia Eagles—and several teammates met with then-Philadelphia police commissioner Richard Ross to push for reform.

Jenkins hopes his piece, that aired Sunday night during the ESPYs, similarly galvanized athletes to act. A viewer discretion advisory opens up the segment. “The following presentation contains images that may not be appropriate for all audience,” it reads. The powerful clip starts with 12-year-old gospel singer Keedron Bryant singing his heart-wrenching hit, “I Just Wanna Live.” Pictures of Black men and woman killed, in many cases by police — including Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and Floyd — flash across the screen. Jenkins appears, calling on athletes to take stands in the mold of Muhammad Ali, Tommie Smith, John Carlos, Arthur Ashe, Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf and Colin Kaepernick. We see the painful image of former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin kneeling on George Floyd as he calls out for his mother, as the viewer hears the voice of singer Mumu Fresh.

Athletes like Ibtihaj Muhammad, the first Muslim American woman to win a medal at the Olympics, NASCAR driver Bubba Wallace, whose public pressure compelled NASCAR to ban the Confederate flag at its races, and NBA star Donovan Mitchell speak. Muhammad talks in the piece about the pain of seeing Floyd’s death unfold on video. “It’s always really hard for me to see the faces of people who have died as a result of police violence,” Muhammad, a co-founder of Athletes For Impact—an organization that works closely with athletes on activism—tells TIME. “They conjure up memories of just those moments in time where we’ve all seen the videos, or had to hear about these unfortunate ways they’ve passed. And to know that nothing has changed is difficult.”

A montage of police violence against Black women follows. Mitchell makes a direct appeal for white athletes and sports figures to step up. Diana Taurasi, Breanna Stewart, Zach Ertz, Julie Ertz, Lindsey Vonn, Steve Kerr, Kyle Shanahan, Chris Long and Mark Cuban make calls for action. Newark Mayor Ras Baraka lays out calls for justice, in spoken word: “And we need it now, we need it now, we need it now,” he says.

“This is the tipping point,” Jenkins says in closing. “There is no going back, there is no inching forward.” The video ends noting that “as of June 21, none of the three police officers who murdered Breonna Taylor have been arrested.”

To Jenkins, the piece is a call to action for athletes. “I want this to be one of those moments where, if there are any more people left on the fence, that they get off of it,” Jenkins tells TIME. “Right now is probably the safest moment to get involved. It’s also a very vulnerable time in my mind. Because, it is now sexy to protest and to stand up using your voice. And so I want to make sure everyone who gets involved is doing it from a place of real understanding and power, not just out of guilt or public pressure.”

Jenkins hopes more white athletes engage. “It shouldn’t be the responsibility of Black people to tell white people what to do,” says Jenkins. “They should take it upon themselves to learn, research what’s going on, understand our system, just like we had to do.” Why are white allies so important? “If we take the context of sports out of it, and just talk about us as a country, these issues that we’re dealing with were put in by a white majority,” says Jenkins. “And the reason we can’t just eradicate these things is because the victims of these system, the minorities, don’t have enough votes or voices to just flip this on our own. Otherwise we would have. So this whole movement, really, is going to be taken across the finish line on the backs of white people.”

“When you allow people to stay silent, they are no longer responsible for that happens,” says Jenkins. “My challenge is for them to get involved not just by statement or by tweet, but by real action. We have this moment right now, that is driven by guilt. But guilt runs off eventually. So I think the time right now, while we have everyone sitting still, is a great time to really deal with the truth and reconciliation. We’ve never dealt with the truth of where we are. We’re in that moment now. And so I’m challenging my white peers to not only, hey, denounce racism. That’s the easy part. How do you learn about the actual oppression that we’re talking about? How do you learn about how you may be even participating in it, or perpetuating it? Are you going to figure out how you’re going to participate in tearing this stuff down?”

In May, Golden State Warriors coach Steve Kerr added his name to a letter put forward by the Players’ Coalition, the social justice organization co-founded by Jenkins and former NFL wide receiver Anquan Boldin, calling for a federal investigation into the death of Arbery. Given his respect for Jenkins, he was happy to participate in the production—in the clip, Kerr warns against conflating kneeling with disrespect for flag and country. “Athletes and entertainers, people with a platform can help spread awareness,” Kerr tells TIME. “But ultimately, to me, it’s white people in places of economic and political and corporate power who are gong to be the ones to really create change. People can demand that of them. And that’s what’s going to happen.”

Jenkins’ own work offers a blueprint for how all athletes can fight for change. In Philadelphia, he kneeled with protestors in the street after Floyd’s killing, wrote on op-ed in the Philadelphia Inquirer calling for a deescalation of police violence, and on June 6, addressed a crowd at the African-American Museum in Philadelphia, calling for a divestment from police and investment into Black business, education, housing and wellness. Fourteen members of the Philadelphia City Council, days later, sent a letter to the mayor objecting to a $14 million increase in the police budget. On June 17, the City Council gave preliminary approval to a budget that could reduce police funding by $33 million. “As athletes, we have the ability to not only raise awareness for an issue, but when it comes to policy, being able to talk to legislators, talk to elected officials, being able to put pressure on them because we are who we are, we bring cameras,” Jenkins says. “We oftentimes come from these same neighborhoods and communities that need help, so we can articulate the pain sometimes better than these politicians do.”

He wholeheartedly supports calls, heard around the country, to defund police. “Most people support defunding the police,” Jenkins says. “A lot of people struggle with the phrasing more than they struggle with the concept. Most of us, including leadership in law enforcement, believe that we ask police officers to do too much. They’re not trained to deal with mental health issues, they’re not trained to deal with homelessness, they’re not trained to deal with domestic disputes, they’re not trained to deal with kids in school, they’re not trained to deal with a number of things we ask them to respond to. We talk about deescalation, deescalation, deescalation. It’s impossible to deescalate a situation when you have someone who brings a firearm into it. So that becomes intimidation. And that’s what we see. If you don’t submit to that intimidation, ultimately somebody will get killed.”

“Defunding is just taking away the excess money that goes to our police departments, that push them to do a job that they don’t want to do, and we don’t want them doing,” says Jenkins. “And making sure we push them to be highly trained, to have all of the accountability they need. We need to redefine the role of policing in our community.” A world where the current policing blueprint isn’t necessary, Jenkins says, is worth striving for. “The end goal is, yeah, to live in a society where we don’t need the police,” Jenkins says. “I don’t think anybody wants to just literally with a swipe of a pen in 2020 eliminate all policing without creating some kind of other model, or transitioning into some other model of safety. But I think we all want to get to point where we don’t need armed people responding to our citizens. That we create a society that is equitable, that does not have extreme poverty, that does not have people living in these traumatic places. Crime drops because there is more opportunity.”

Jenkins, whom CNN just hired as a contributor to comment on social justice issues, is still training for the upcoming NFL season while producing videos, making TV appearances, talking to athletes about pushing their platforms for change—he recently did a Zoom call, for example, with members of the Washington Wizards and Washington Mystics—and continuing his activism work. While Jenkins appreciated NFL commissioner Roger Goodell’s recent video supporting Black Lives Matter and a players’ right to protest, he needs to see more. “I think the first step is acknowledging what Colin Kaepernick stood for,” says Jenkins. “Him in particular. Not players in general. What he stood for and what he put on the line. And now, where we are as a country, give him his ‘I told you so’ moment. That’s the first thing. And then secondly, we all want to see him have an opportunity to play. What that looks like I don’t think anybody knows. I think a workout or a tryout is a very simple thing to do. There are two sides to that relationship, so we’ll see.“

Jenkins acknowledges the NFL’s work in giving money to social justice causes, and creating awareness campaigns. “But we can’t take you serious because of the Colin Kaepernick situation,” Jenkins says. “We don’t know where your heart is. If they want to really help, and not be a voice in this fight that is confusing or muddies the water, the first thing they need to do is take on this Coin Kaepernick issue head on, and start there.”

Mostly, Jenkins believes America has an opportunity to break the cycle of injustice, outrage, and a return to injustice. “Right now, more than any other time in my lifetime, it feels like we have the ability to literally to turn away from the systems that we’ve had for centuries, and actually start over,” says Jenkins. “Everybody is starting to pay attention. This is a moment where we can reimagine how our society functions. All of our systems were birthed out of white supremacy. And so reform doesn’t change the origins of the system. They just kind of tailor it. But it’s still heading in the same direction. Until we turn our backs on those systems and restart America, until we understand the truth of where, how we got there, and what our roles are, then we can get to that place of reconciliation.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- TIME’s Top 10 Photos of 2024

- Why Gen Z Is Drinking Less

- The Best Movies About Cooking

- Why Is Anxiety Worse at Night?

- A Head-to-Toe Guide to Treating Dry Skin

- Why Street Cats Are Taking Over Urban Neighborhoods

- Column: Jimmy Carter’s Global Legacy Was Moral Clarity

Write to Sean Gregory at sean.gregory@time.com