On Monday night, while threatening military intervention to suppress nationwide protests against police brutality, Donald Trump declared himself the “President of law and order.”

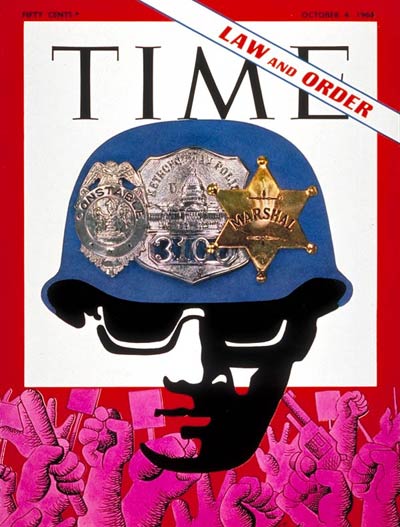

It wasn’t the first time Trump had invoked those three words. Just a day earlier, he had tweeted simply: “LAW & ORDER.” Observers have drawn parallels between the 1960s and the current period of unrest, which began following the death of George Floyd after a police officer knelt on his neck for more than eight minutes; in particular, many pundits have seen particular echoes of Richard Nixon’s 1968 Presidential campaign.

Back then, following revolts in 125 cities nationwide after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. and throughout the mid-1960s, fueled by inequality issues yet to be addressed, Nixon made “law and order” a centerpiece of his platform. “Law and order” might sound simple, a 1968 TIME cover story on the campaign pointed out, but to some it was “a shorthand message promising repression of the black community”—and to that community, it was “a bleak warning that worse times may be coming.”

But Elizabeth Hinton, a historian of U.S. inequality and author of From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime: The Making of Mass Incarceration in America, says the focus on Nixon obscures the real Presidential origins of modern “law and order.” Nixon’s predecessor, Lyndon B. Johnson, shaped decades of policy when his Administration decided to invest more in policing than in social welfare programs — and, as Hinton explains, that history is key to understanding why the issues that sparked the protests over the last week remain unresolved. She spoke to TIME about what to know about that past.

TIME: Are there any particular moments from American history you think are parallel to what we’ve been seeing in the days since George Floyd’s death in Minneapolis?

HINTON: There are a number of obvious parallels, but also really important differences, between what we’re seeing in the streets of American cities today and the 1960s. The proximate cause of the unrest being police violence and the underlying issues that have fueled the protests, which are continued racial equality and discrimination and socioeconomic exclusion, are really at the heart of both. In the 1960s, even though there was an attempt on the part of federal policymakers to address [those issues], their solutions did not go far enough. Ultimately they embraced a set of policies that continued the very same violent conditions that had led to the original unrest in the 1960s in the first place. We’re still very much struggling with the unfinished legacy of Reconstruction and the enduring racism that pervades American society. And until that’s addressed, these flames will continue.

When you talk about policies and solutions that didn’t go far enough, which examples do you have in mind?

In the middle of the Detroit uprising in 1967, Johnson called for the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, known as the Kerner Commission. This group studied the nature of urban unrest in a number of American cities, and basically called on the federal government to begin to make massive investments in urban institutions — schools, housing, job-creation programs. The Kerner Commission famously said, unless the federal government is prepared to make massive investments in these communities that are experiencing this unrest, “Our nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white — separate and unequal.”

The Johnson Administration and many other liberal policymakers thought this was too radical, and, as I discovered in my research, ended up, long-term, embracing a set of policies that managed problems of poverty and inequality through policing and surveillance of low-income communities and incarceration. And so that choice — that investment in policing and divestment from social welfare programs — is exactly the conditions that led some 50 years later to Derek Chauvin jamming his knee in George Floyd’s neck.

So even though lots of people have traced these ideas to Nixon, your research shows the strategy goes back to the Johnson Administration.

The kind of incidents that garnered the national attention and the news coverage that we’re seeing today, that was an occurrence that Johnson had to deal with during every single summer of his presidency, and we haven’t experienced anything like it since then. We think about “law and order” [as a modern political strategy] originating during the Nixon Administration, but Johnson was the President who called for the War on Crime, who began the unprecedented federal investment in local police forces as his formal strategy to prevent future urban unrest. That strategy of preventing unrest and managing poverty through policing has not worked. What we’re seeing today is a really clear expression of the failures of that approach.

Do you think there’s anything people are getting wrong about the sequence of events in 1968, from King’s assassination to revolts in cities and then Nixon winning the election on a “law and order” platform?

Yeah, that’s not accurate. We have to go back to 1964 when Johnson calls the War on Poverty, and the Civil Right Act passes in July. Harlem erupts into days of unrest after the beating of a 15-year-old by NYC police and this leads to unrest in Chicago and other places, in a very similar style to what we’re seeing now. The following summer, Johnson calls for the War on Crime. Then a few months later, Watts erupts in L.A. in 1965 and then we have subsequent instances of unrest and then the really large moment in the summer of 1967 in Newark and Detroit, and the incidents in 125 [cities] after the assassination of King in 1968. These things had been happening for years before, every summer, in the face of War on Poverty programs that didn’t go far enough.

I thought Johnson was known for the Great Society programs and the social-welfare system that they created.

I wrestled with this too when I started doing this research. Johnson is very complicated. I really do think Johnson had good intentions, that he launched the War on Crime as a way to improve American society as he saw it.

But just like many policymakers throughout history and many policymakers today, his own racial assumptions limited the vision of what that War on Poverty could be, and [are] why he and others refused to commit and devote the resources that might address issues of racial inequality and poverty in a meaningful way, as his own Kerner Commission called for. Many liberal policymakers started to turn away from these social-welfare investments as a way to confront issues of racial inequality and poverty, and to embrace this more punitive vision for dealing with urban crisis. Out of that Great Society we get a major job-creation program for police officers, but not the residents who were intended to benefit from the War on Poverty programs.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

Are there any milestones in policing decisions or strategy since the ’60s that provide context for Floyd’s death in 2020?

The Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act of 1968 was the capstone to Johnson’s Great Society. While he signed it a few weeks after the riots after King’s assassination had subsided, his administration had been carefully writing that legislation and shaping it as it made its way through Congress since 1965. It’s the last major piece of domestic legislation he signed before leaving office, which really began a more permanent national investment in the War on Crime.

In the 1980s and 1990s, the strategy of “broken windows” or zero-tolerance enforcement really fueled the saturation of police in low-income communities of color and exacerbated the strategy of arresting people for misdemeanor offenses that fueled mass incarceration in many respects. A lot of these strategies fall under the rubric of community policing, which can be very vaguely defined and means different things to different people. The Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, passed under Clinton, invested billions to hire 100,000 new community policing officers on the streets of American cities while simultaneously investing billions to expand the prison system. It endorsed this kind of zero-tolerance policing that was already underway in major cities like Chicago and NYC and helps us understand, most directly, how we got to this mass-incarceration society.

Does policing in Midwestern cities like Minneapolis differ from policing in other parts of the country?

Significant black communities tend to be in Midwestern cities that suffered from extreme de-industrialization — cities like where my family is from, the plant town Saginaw, Michigan. General Motors in the 1940s sent my grandpa a ticket to Saginaw. The plant closed, everyone who could leave did, but not everybody could leave. Those who remain have become even more isolated in the absence of real economic infrastructure in these communities. In places like Ferguson, the criminal justice or law-enforcement apparatus fuels public works through fines and fees and those kinds of initiatives. In places where that’s not the approach, the majority of city budgets end up going to police departments, to crime-control programs, rather than schools and housing and other social welfare programs.

Given the links people are drawing to past summers of uprisings, is there something about summertime that contributes to tensions running high?

You do see these incidents rarely in the winter, but you see them in the fall and spring. Part of it is, it’s hot, people are outside and when poor people, when people of color are outside, they tend to be policed more heavily, especially when — again, this is why the context of these incidents unfolding as the War on Crime is escalating from 1965 onward really matters — there are more police on the streets who are increasingly being equipped with military-grade riot prevention gear. And instead of stopping future unrest, in many cases, the investment and widespread deployment of police forces on the streets of American cities may have done the opposite.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com